Incidents involving unexploded ordnance and remnants of war have become an almost daily occurrence across Syria, endangering the lives of civilians, military personnel, and demining teams alike. Even eleven months after the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, this deadly legacy continues to claim lives and inflict serious injuries.

These remnants stretch across much of Syria’s territory, posing a dual threat to daily life and the national economy. Their widespread presence hinders the return of displaced persons, disrupts vital sectors, slows reconstruction projects, and deters investors. Syria remains among the most heavily contaminated countries in the world with war remnants.

According to United Nations estimates, more than 65% of Syria’s population roughly 14.4 to 15.4 million people face direct threats from explosive remnants of war, an increase of nearly 20% from 2023. For the third consecutive year, Syria has recorded the world’s highest number of casualties from explosive ordnance.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights has documented the deaths of 3,521 civilians due to landmine explosions since the uprising began in 2011, including 931 children and 362 women, and the injury of no fewer than 10,400 civilians. Meanwhile, roughly 16.7 million people still require humanitarian assistance in one of the world’s most dire humanitarian crises.

A Country Littered with War Debris

Since March 2011, all parties to the conflict and controlling forces have laid landmines across vast areas of Syria, most notably the Assad regime, which had used mines prior to 2011 but escalated their use following the outbreak of protests and the armed conflict that followed. The ease of manufacturing and low cost of mines made them an accessible weapon, often deployed without any regard for mapping or future removal.

Over the years, the former regime and its allies have left minefields and munitions in towns, farmlands, and military zones, often hidden under rubble or behind doors, using them as tools of reprisal. Displaced populations remain among the most vulnerable to these remnants, which are among the deadliest hazards of war.

Following the launch of Operation “Deterring Aggression” and the fall of Assad’s regime, the scale of Syria’s contamination has gradually come to light, especially as returning civilians have encountered explosive hazards in frontline zones and long-abandoned villages.

No comprehensive statistics exist on the total number of war remnants in Syria, but experts and mine action organizations confirm widespread contamination with a variety of explosive devices, including homemade bombs, abandoned munitions, landmines, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Over 14 years of conflict, it is estimated that around one million explosive devices were used. Given the failure rate of ordnance typically ranges between 10% and 30%, Syria may now harbor between 100,000 and 300,000 unexploded items embedded in critical infrastructure roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, homes as well as in agricultural lands, irrigation systems, and groundwater layers.

An estimated eight out of ten agricultural fields in Syria are contaminated, directly affecting livelihoods in a country where a significant portion of the population depends on farming for survival.

Civilian Casualties on the Rise

According to HALO Trust, a global organization dedicated to explosive hazard removal, Syria is now the second most dangerous country in the world after Myanmar when it comes to civilian casualties from explosive remnants. The organization confirms that both urban and rural areas remain saturated with cluster munitions, landmines, and other lethal explosives.

In a statement to Noon Post, HALO Trust noted that as millions of displaced Syrians return from neighboring countries like Lebanon and Turkey, the risk of accidents has risen sharply. More than 1,400 casualties have been reported since Assad’s fall, and emergency calls have increased tenfold following the return of over a million people.

The organization also highlighted the devastation of urban environments entire neighborhoods destroyed by barrel bombs and artillery. Syria is flooded with weapons and explosive materials, fueling illicit arms trade, ISIS attacks, and frequent ammunition depot blasts.

Raed al-Hassoun, head of the Syrian Civil Defense’s Explosive Ordnance Unit, reported that from the beginning of 2025 to the end of September, the group responded to 120 incidents caused by remnants of war in 69 areas. These explosions killed 110 people, including three volunteers, and injured 307 others, including four volunteers. He attributes the rise in casualties to the uncoordinated return of civilians despite the heavy contamination and absence of maps indicating minefields.

Following the regime’s fall, the Civil Defense increased its demining efforts, destroying around 2,500 explosive items most of them cluster munitions and conducting 750 community assessments. They identified 550 areas contaminated with unexploded ordnance. One of the gravest challenges, al-Hassoun noted, is the irregular distribution of minefields and the lack of maps marking them.

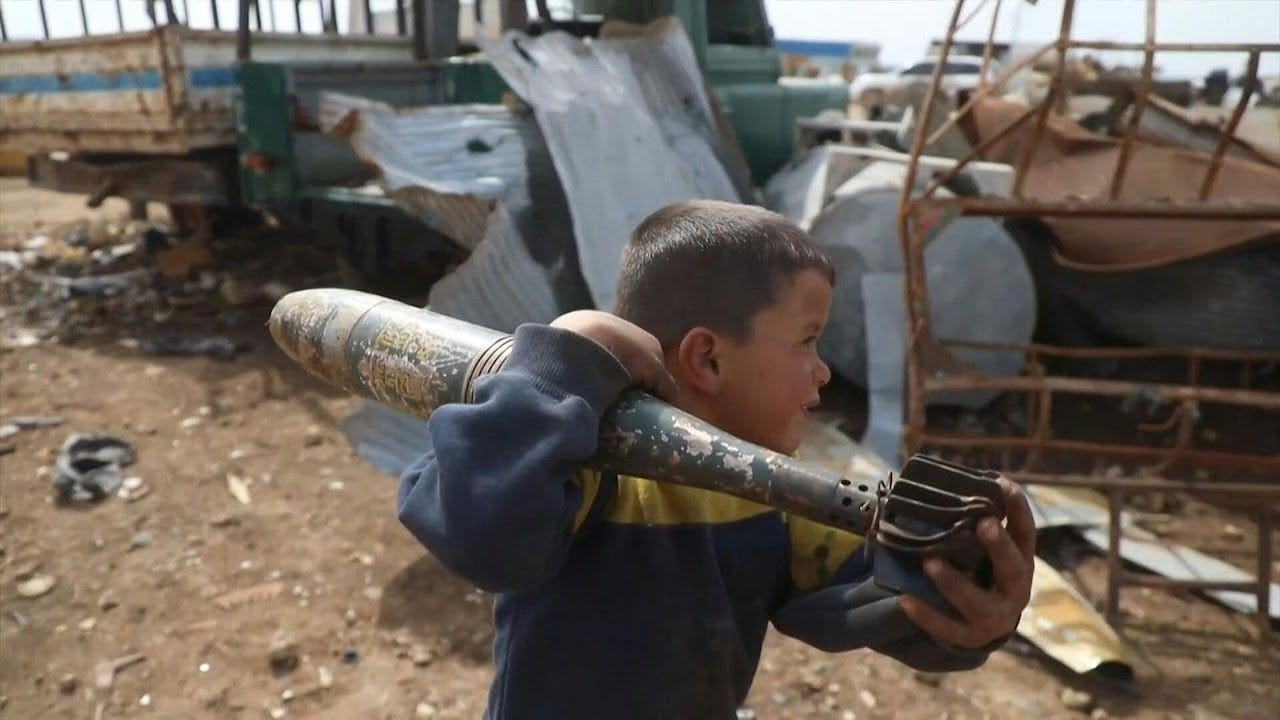

Children are the most affected demographic, with around five million children living in areas contaminated with landmines and unexploded ordnance now the leading cause of injuries among children in Syria. In December 2024 alone, UNICEF documented the death or injury of 116 children about four per day while actual numbers may be higher due to the complex humanitarian situation.

A Major Obstacle to Recovery and Reconstruction

War remnants are among the most significant obstacles to Syria’s economic recovery. They hamper reconstruction efforts estimated by the World Bank to cost $216 billion and hinder the return of nearly seven million internally displaced persons, even as the new Syrian administration seeks to attract investments and revive stalled economic sectors.

Mines have also impeded firefighting operations and endangered first responders during large-scale wildfires—most notably in coastal forests in July, where over 15,000 hectares of farmland and woodland were destroyed.

HALO Trust confirms that widespread contamination particularly in rural areas directly impairs the cultivation of crops, one of Syria’s key economic exports. It stresses the importance of weapons and ammunition management, emphasizing that Syria must eventually remove these remnants from circulation. Without such action, the political threat posed by unexploded ordnance may outweigh even its long-term economic damage.

In an interview with Noon Post, economic analyst Abdul Azim al-Maghrebi noted that war remnants directly impact agriculture, infrastructure, energy, and tourism. Mines continue to make farmland unusable, reducing output and threatening food security.

He added that unexploded ordnance complicates reconstruction and raises investment risks, deterring both domestic and foreign capital from entering affected areas, thereby slowing economic recovery and development. Ongoing insecurity also discourages the return of workers and residents, prolonging the costly and difficult rebuilding process.

These remnants also destroy ecosystems and pollute water sources, exacerbating the health and economic burden on the population and diverting public spending from development projects to mine clearance and healthcare.

While both government bodies and volunteer teams are working to clear Syria of explosive remnants, efforts range from survey and removal to public awareness campaigns and rehabilitation services. However, these initiatives remain fragmented, with no unified coordinating authority.

HALO Trust stated that a coherent coordination body for mine action has yet to be established in Syria. The organization expressed hope for cooperation with authorities to map and remove mines and to establish a legal framework for addressing these risks. It also urged Syria to join the Ottawa Treaty banning landmines in order to benefit from international expertise and resources.

Human rights and humanitarian groups including Human Rights Watch recommend the establishment of independent, civilian-led national institutions dedicated to mine action, including a national strategic body and a center for operational coordination that adheres to international mine action standards.

They also call for the centralization and sharing of mine data across agencies, prioritizing demining, allocating sufficient funding for surveys, risk education, personnel training, and victim support.