A Long Journey to the Sacred House: Why Palestinian Citizens of Israel Missed Mecca for 30 Years

In the wake of the 1948 Nakba, Palestinians found themselves just three lunar months away from the Hajj season. Yet amid the devastation of displacement, the depth of loss, and Israel's seizure of most of their homeland—with only a small fraction managing to stay—the only urgent religious duty on their minds was to return to their ancestral homes.

However, the Zionist militias, more organized and battlefield-savvy, booby‑trapped return routes with explosive devices and executed retaliatory terror, severing families and fragmenting Palestinian communities into Christian, Muslim, Druze, Circassian, Bedouin. They imposed a military regime that stripped Palestinians of their identity—national, cultural, and religious.

Soon, public display of the Palestinian flag became a crime, attending mosques became outlawed, celebrating Islamic holidays was forbidden, and traveling abroad for Hajj turned into a one‑way endeavor. Arab states, hostile to Israel’s new reality, tightened border access, leaving Palestinian citizens under Israeli rule completely isolated from the broader Arab and Islamic world. Their aspiration to perform Hajj remained a distant dream—one that lingered for decades.

“Palestinian-Israeli” on the Threshold of Mecca

Days after the Nakba, some 160,000 Palestinians—out of 1.4 million—were forcibly absorbed into the nascent Israeli state. This demographic upheaval continued with the 1949 Armistice, but another form of catastrophe followed: the onset of military law, which lasted nearly two decades. Under this regime, Palestinians were deprived of gathering for weddings, mourning rituals, mosque congregations, Ramadan rites, Eid celebrations—and the Hajj.

Israeli authorities early on sought to isolate Palestinians by issuing them limited-travel Israeli travel documents, unrecognized by most countries, including Saudi Arabia. Arab states, refusing to normalize relations, closed their borders to those holding these documents—even devout Muslims. Thus, Palestinians from “48” were entirely barred from Arab nations, including Saudi Arabia.

While they circumvented Israeli university restrictions by studying abroad, Hajj remained unique: irreproducible anywhere but Mecca. Without rutas via Israel, and with Saudi Arabia upholding pan-Arab solidarity, pilgrims with Israeli passports were turned away.

But in 1978, a breakthrough occurred. Through channels including Sheikh Abdullah Nimr Darwish, Jordan’s Ministry of Awqaf, and Turkey, Saudi Arabia agreed to allow Palestinian citizens of Israel to perform Hajj.

Israel and King Hussein of Jordan signed an agreement placing pilgrims under Jordanian guardianship: Jordan would issue special travel documents and coordinate pilgrim logistics via licensed religious tourism agencies. The initial delegation was designated special by King Hussein’s order.

Hajj Under Oslo’s Shadow

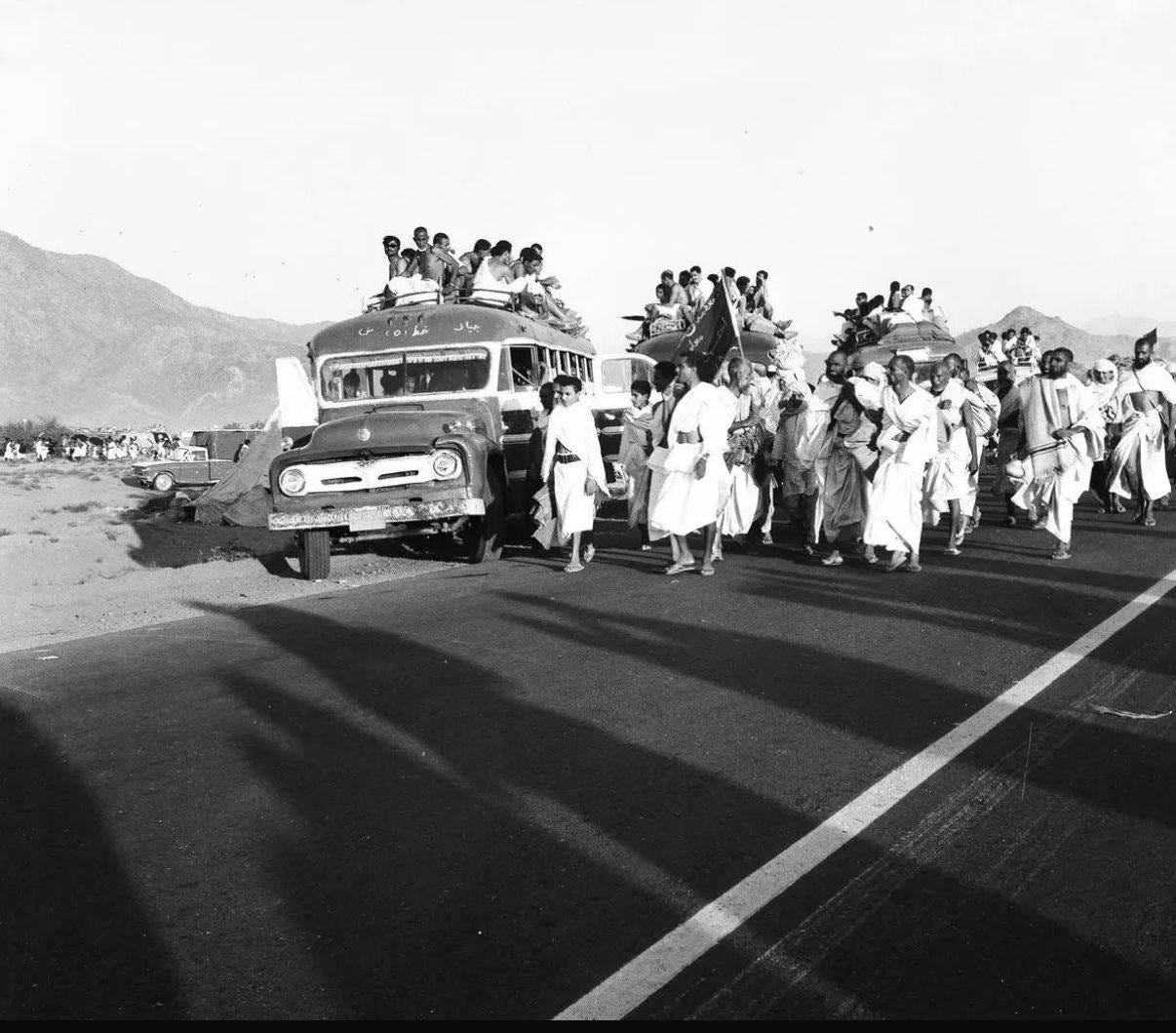

Even after that relief, pilgrims—still chaperoned by Jordan—faced burdens. Flights to Jordan cost around US$600 and land travel through Israeli checkpoints took at least 24 hours. Nonetheless, Jordanian-issued passports opened doors. Pilgrims were housed with the Jordanian mission in Mecca, Medina, Arafat, and Mina; they received medical and spiritual services from Jordanian delegations.

Following the Oslo Accords in 1994, the Palestinian Authority assumed responsibility for West Bank and Gaza pilgrims. In 1995, an official Palestinian Hajj delegation included Palestinians from inside Israel, traveling on Israeli passports supplemented by PA permits, enjoying services equal to what they had under the Jordanians.

But obstacles remained: quotas were low, travel agents inflated prices, and administrative control oscillated between the Ministry of Awqaf and the Hajj Authority. As a result, most continued relying on Jordanian-tourist facilitated arrangements.

Hajj as a Trojan Horse for Normalization?

Unlike other forms of normalization, Saudi-Israeli overtures over Hajj emerged through facilitating pilgrims—a backdoor route. But in 2018, Saudi Arabia barred holders of “temporary” Jordanian passports, affecting about 4,500 Palestinian citizens, signaling a shift. Critics saw this as a nudge toward normalization: no objection to those with permanent Israeli passports, but denying others. Hajj costs soared to ₪29,700 (~US$8,493).

In early 2020, Prime Minister Netanyahu announced plans to fly pilgrims directly from Ben-Gurion Airport in Israel to Saudi Arabia; Likud leaders proposed fares capped at ₪5,000. Palestinians in Israel protested. Then Israeli Interior Minister Aryeh Deri announced visa issuance for “Israelis”—Jewish or Palestinian—to Saudi Arabia, echoing Trump-era state visits from Israel to Saudi Arabia.

Gulf countries, particularly the UAE and Bahrain, began opening services for travel from Israel. Yet final transfer of pilgrim administration from Jordan to Israel stalled. Then the October 7, 2023 war obliterated these emerging normalization hopes.

Today, Palestinians in Israel still gain access to Hajj—but at high cost, under Jordanian auspices, and under political strings. Saudi Arabia insists “religious space must be apolitical,” yet Hajj remains one of the kingdom’s strongest geopolitical instruments—used to reinforce its influence—where “piety serves politics.”