“Apo’s Story”: Abdullah Öcalan’s Journey From Dreaming of a State to Imprisonment on the Island

"My condition is unlike that of any other human, and I don’t want it to resemble theirs—or at least that’s how I’ve understood and felt it. I am on the right path."

This is how Abdullah Öcalan described his life in Imrali Prison in the Sea of Marmara in 2004. While he may be correct in claiming his situation is unique, we cannot say the same for his belief in being on the right path, given his responsibility for the deaths of thousands under the pretext of establishing a Greater Kurdistan.

Öcalan’s dream of achieving justice for the Kurdish people, who long lived as an oppressed minority, led him and his comrades to found the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). The party soon attracted a broad swath of Kurds aspiring to the same goal. But under Öcalan’s leadership, the PKK chose a path unlike other Kurdish movements: it made armed struggle its primary vehicle.

For years, the PKK was the defining force in one of Turkey’s bloodiest historical chapters. Even after Öcalan's arrest, he continued directing the party from prison, maintaining his influence and the party's threat.

This article revisits Öcalan’s own account of his life, deconstructs pivotal stages that led to his exceptional status, and tracks the evolution of his ideology—from founding the PKK to ultimately calling for its disarmament and dissolution.

The Search for Identity

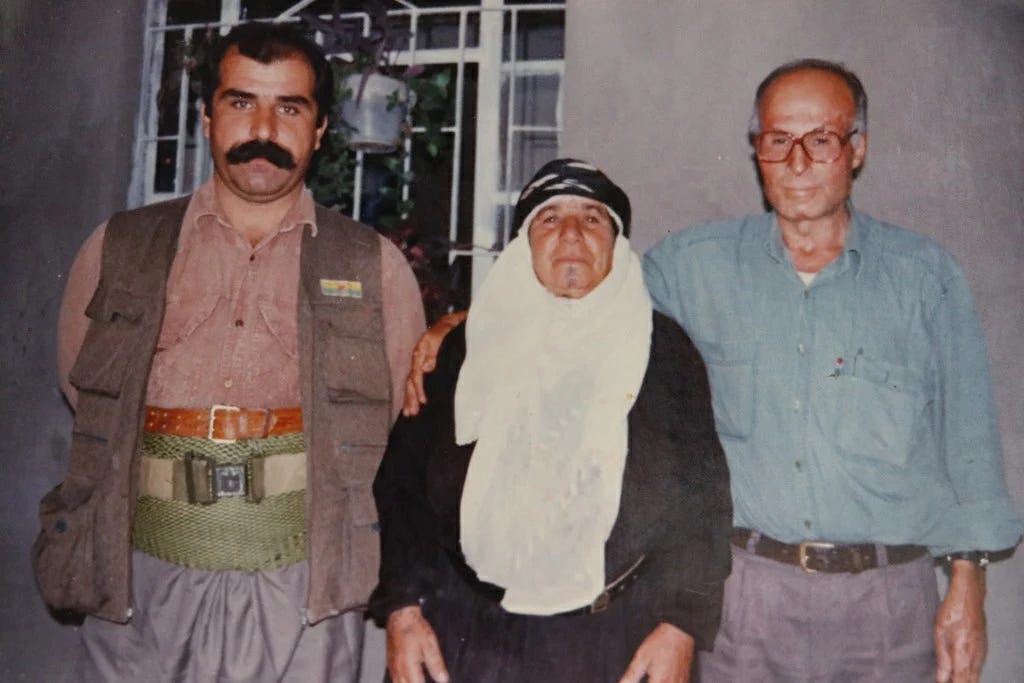

Born on April 4, 1948, in the village of Ömerli in the Hilvan district of Şanlıurfa province, southeastern Turkey, Öcalan was the third of nine children in a poor farming family. He completed elementary school in nearby Cebin and moved in 1963 to attend middle school in Nizip, Gaziantep, where his sister lived. He studied there for three years.

His impoverished and harsh upbringing shaped his combative personality. His mother, known for her fiery temperament, fostered in him a spirit of vengeance. One anecdote describes her encouraging his first act of violence during a childhood altercation.

Öcalan recalled: "I told my mother: you committed a grave mistake by bringing me into this world. If you can't provide for a child or raise him with honesty and strength, how can you face him as a mother? I confronted her and decided, as a child, to live alone—a life to be won through struggle."

The 1960 military coup left a lasting impact on him, linking power with militarism from an early age. Although he failed the entrance exams for military high school, he carried the disappointment for life. In 1966, he enrolled in a vocational school in Ankara, where his political thinking began to form.

By the end of high school, he embraced socialism after reading Leo Huberman's "The ABC of Socialism," declaring: "Muhammad lost; Marx won."

He then worked in Diyarbakır as a land registry technician while preparing for university. Admitted to Istanbul University's law faculty, he soon transferred to political science at Ankara University in 1971, seeking deeper ideological engagement.

The Turkish Left: Political Awakening

In the midst of ideological polarization, Öcalan aligned with the left. At Istanbul University, he joined leftist student circles and observed the activities of the Eastern Revolutionary Cultural Associations (DDKO), which had broken away from mainstream Turkish leftist groups.

He was deeply influenced by Mahir Çayan, leader of the People's Liberation Front of Turkey, who advocated for Kurdish rights. Çayan's death in a 1972 shootout and the execution of three socialist youth leaders profoundly affected Öcalan.

Öcalan led protests after Çayan's death and was arrested on April 7, spending six months in Mamak military prison. Upon release, the student movement saw him as a natural leader, filling a void left by the assassinated icons. But he soon became disillusioned with the Turkish left's reluctance to prioritize the Kurdish issue.

Though early on he leaned toward Turkish leftism, he found the Kurdish left's approach lacking. He criticized the DDKO's elite-driven Kurdish nationalism as hollow and overly class-based.

Frustrated by their limited vision, which reduced the Kurdish issue to infrastructure needs and deemed self-determination premature, Öcalan began envisioning a new political movement.

Birth of the PKK

The idea of the PKK took shape after Öcalan’s prison release. He gathered like-minded activists, including Kemal Babur and Haqi Karar. Their sense of alienation from other leftist groups bonded them.

Within six months, they held a foundational meeting in April 1973 at the Çubuk Dam, a stage the party would later call the "attempt to create the group."

By 1975, a draft party program had been written, outlining a Marxist-Leninist path to Kurdish national liberation. This would become the foundation for the 1978 PKK manifesto: "The Road to the Kurdish Revolution."

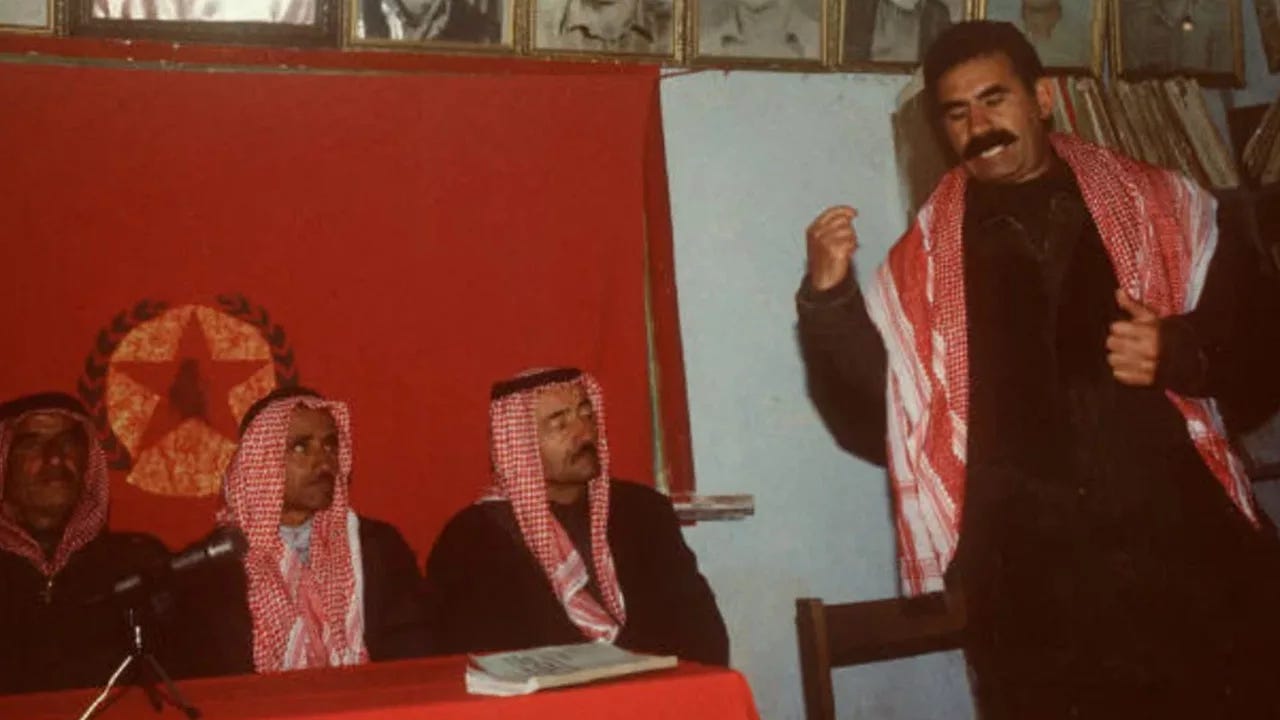

Though not yet formally appointed, Öcalan's leadership was clear—the group became known as "Apocular," after his nickname Apo, meaning "uncle" in Kurdish.

The PKK held its first congress on November 27, 1978, in Fıs village, Diyarbakır. Öcalan was elected secretary-general. The congress adopted key principles:

Establishing a unified, independent Kurdistan

Achieving this through Marxist-Leninist revolution

Embracing revolutionary violence as legitimate

Adopting protracted people's war strategies from Vietnam, China, Angola, and Latin America

Structuring the party into three pillars: party, front, and army

Meanwhile, the Turkish state cracked down, arresting PKK members and intensifying tensions with Kurdish tribes and rival organizations. Despite the instability, the PKK launched its first armed attack against the Boğac Tribe, initiating open conflict with Kurdish tribal leaders.

In 1979, the arrest of PKK member Şahin Donmaz exposed internal secrets, prompting Öcalan to flee Turkey and seek refuge abroad.

Exile in Syria and Party Consolidation

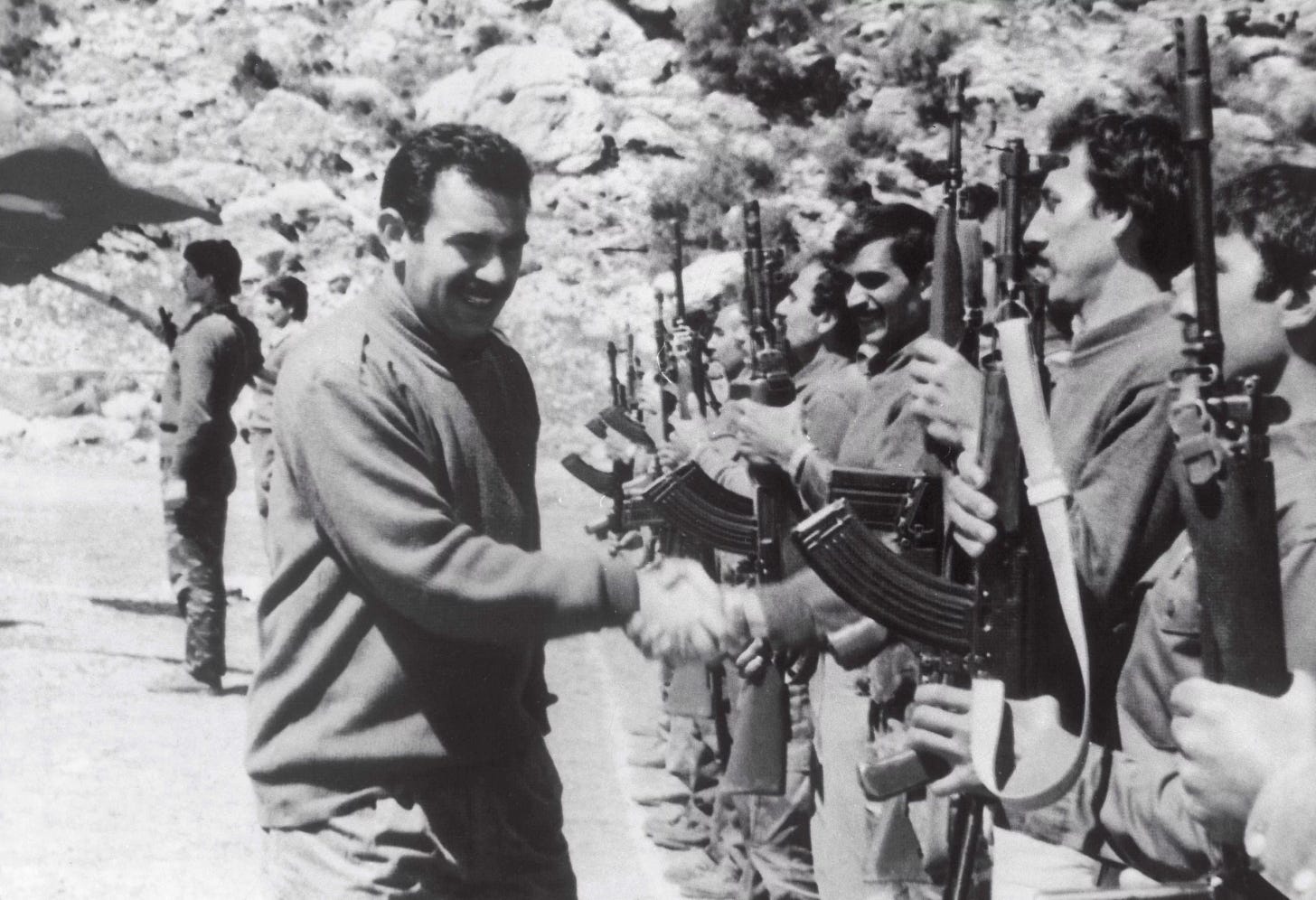

Just days before the 1980 Turkish coup, Öcalan fled to Syria, which became the PKK’s safe haven. From 1979 to 1984, the party built armed training programs in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley and infiltrated Turkey from Syria and Iraq.

The PKK expanded its international reach and built diplomatic ties. The party's third congress cemented Öcalan’s grip, though it revealed internal dissent, especially from imprisoned cadres critical of his authoritarianism.

On August 15, 1984, the PKK launched armed attacks in Siirt and Hakkari, killing Turkish soldiers. Ankara retaliated, sparking a prolonged war.

The 1980s and 1990s saw severe human rights violations by both sides. The PKK committed village massacres to instill fear. In 1985, Turkey responded by forming "village guard" militias, later accused of abuses against pro-PKK civilians.

Toward Negotiation

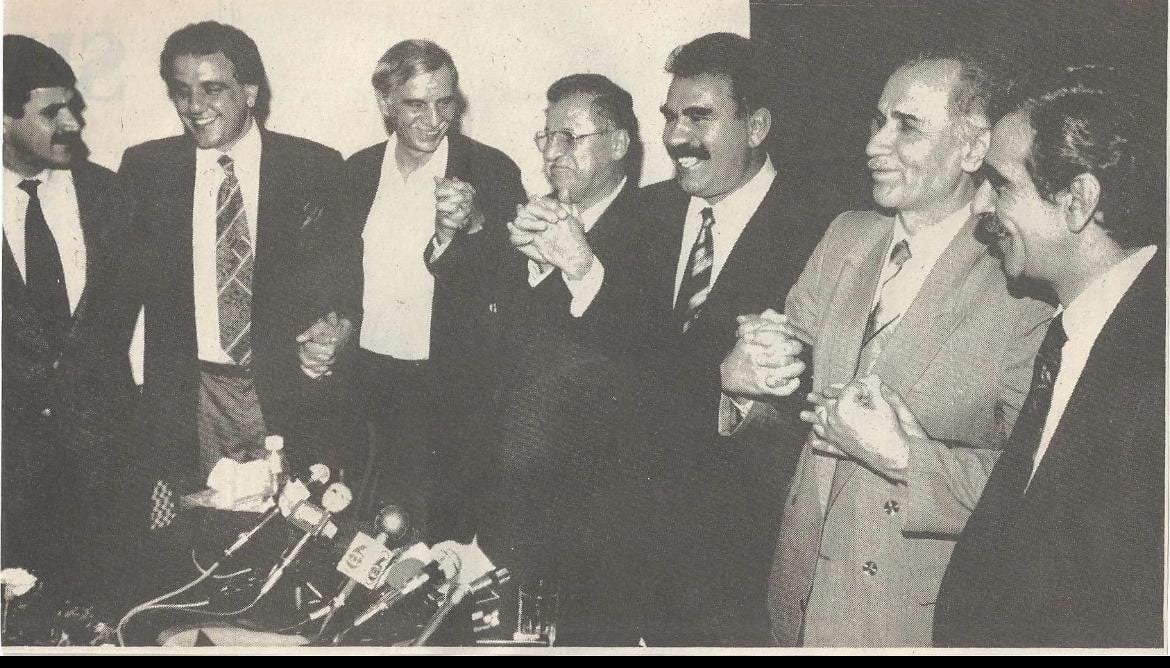

Despite years of bloodshed, moments of political opening emerged. In 1993, Öcalan declared a unilateral ceasefire, aligning with President Turgut Özal’s reform efforts. The truce collapsed after Özal’s death.

Following his 1999 capture and death sentence—later commuted under European pressure—Öcalan again declared a ceasefire. Many PKK fighters withdrew to Iraq. In 2003, the PKK launched the Democratic People’s Congress (Kongra-Gel) as a civilian front.

Peace talks in Oslo (2009–2011) failed, but led to the 2013 peace process. That March, Öcalan's Nowruz message called on PKK fighters to withdraw:

"We’ve reached a point where weapons must fall silent and thoughts and politics must speak."

In 2005, he had formally abandoned the dream of a Kurdish state, proposing instead "democratic confederalism."

The process lasted until 2015, when an ISIS bombing in Suruç killed 32 Kurdish activists. The PKK killed two Turkish police officers in retaliation, ending the ceasefire.

In late 2024, Nationalist Movement Party leader Devlet Bahçeli—a longtime enemy of Öcalan—stated he was open to Öcalan addressing parliament if he dissolved the PKK.

On February 27, 2025, Öcalan issued a prison statement urging disarmament. On May 12, the PKK announced plans to dissolve its armed wing, ending a 40-year insurgency.

Öcalan and the Assad Regime

During his Syrian exile, Öcalan leveraged tensions over water rights and the Hatay province to gain protection from Hafez al-Assad. He didn’t meet Syrian officials until 1992, when Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam engaged him in political discussions.

By 1998, Turkish threats of war forced Syria to expel Öcalan. Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak mediated, leading to the Adana security agreement. Khaddam later recalled:

"I said goodbye to him with tears in my eyes. It’s not easy to tell a man: Go to your death."

Despite Assad's support, Syria denied Kurdish identity domestically, stripping thousands of citizenship and repressing Kurdish activism.

After 2011, the Assad regime covertly backed the PKK’s Syrian branch (YPG), granting autonomy in exchange for loyalty. In April 2011, Öcalan wrote to Bashar Assad: "Give us autonomy and we will support you."

As the revolution became more Islamist, the PKK became wary. In May 2011, Öcalan warned:

"If the Muslim Brotherhood comes to power, there will be massacres against us."

He urged YPG to pursue diplomacy with Assad, showing willingness to support the regime in exchange for Kurdish rights.

After leaving Syria, Öcalan sought asylum in Greece, Russia, and Italy—but no country wanted him. Under U.S.-Turkish intelligence coordination, he was denied refuge.

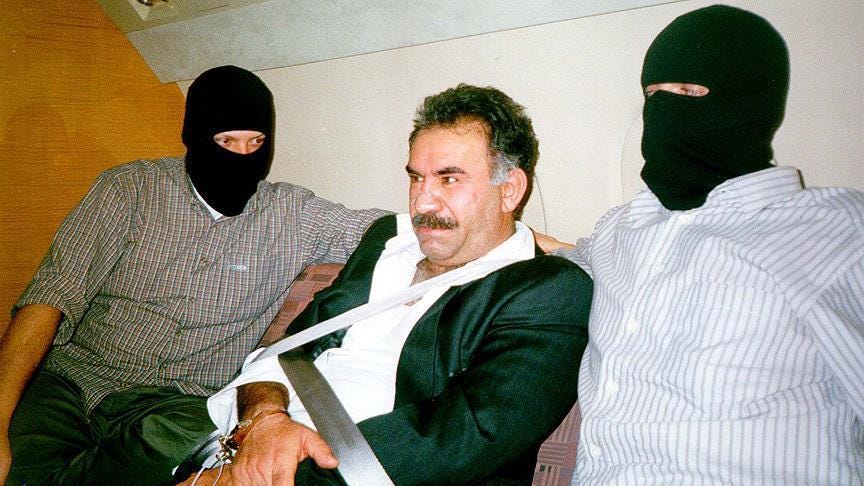

On February 15, 1999, Turkish agents captured him in Nairobi, Kenya. He was flown to Turkey and imprisoned on Imrali Island.

On June 29, 1999, a Turkish court sentenced him to death. Following EU criticism and massive protests, Ankara commuted the sentence in 2002 to life imprisonment.

Iraq: Strategic Base

Öcalan never limited his ambitions to Turkey. In 1982, he met Masoud Barzani, who allowed PKK camps in northern Iraq.

Post-Gulf War chaos in 1991 enabled the PKK to entrench in the Qandil Mountains. Initially cordial, PKK–KDP relations soured as Barzani feared the PKK’s growing influence. A Kurdish civil war erupted from 1994 to 1997, with Jalal Talabani’s PUK siding with the PKK and Turkey backing Barzani.

In 2000, Öcalan, from prison, endorsed fighting the PUK. A PKK insider said the motive was to keep fighters combat-ready.

He described Barzani and Talabani as "cartoonish Saddams" and declared: "They are arms and legs; I am the brain."

Still, Kurdish parties later mediated Turkey–PKK negotiations. In 2020, as tensions rose again, Öcalan called for restoring the 1982 spirit of cooperation.

Israel: Political Tool

Öcalan opposed Israeli occupation from early on and reportedly fought alongside the PFLP in the Golan. Turkish leftists trained in Palestinian camps during the 1970s–80s.

He believed Israeli intelligence pressured Syria to expel him and even warned of Israeli plots to control or eliminate him.

After his capture, PKK supporters blamed Mossad and protested in Berlin, where three Kurds were killed.

From prison, Öcalan denounced Kurdish–Israeli ties in Iraq as a "second Zionism." But divisions existed within the PKK: Murat Karayılan advocated for ties if Israel apologized for its role in Öcalan’s capture.

A PKK official told Israeli press in 2019: "The region needs Israeli expertise. Let’s break barriers and build mutual understanding."

Still, no formal relations emerged. In a leaked meeting transcript, Öcalan warned of an Israeli five-step plan to dominate the region:

"Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria are finished. Only Iran and Turkey remain."

He feared Kurdish regions might become the "next Gaza."

Yet journalist Ruşen Çakır argues that Öcalan isn’t driven by hatred of Israel, but by resistance to regional domination—using his stance as leverage in Turkish negotiations.

Symbol and Legacy

Though imprisoned, Öcalan remains the PKK’s spiritual and ideological leader. His pronouncements, even from isolation, dictate the group’s direction.

His influence transcends Turkey, shaping Kurdish politics in Syria, Iraq, and Iran. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) regard him as their ideological father.

In every peace effort, he is the central figure. In 2013–2015, he called for abandoning armed struggle. In 2025, he brought the PKK to its end.

He has reshaped his vision from separatism to democratic autonomy. Though his actions led to bloodshed, his final act may define a new political future.

Returning to his own words:

"My condition is unlike any other—and I am on the right path."

History, perhaps, will be the judge of whether that path was truly the right one.