On April 22, 2025, under a bright midday sun in the lush meadows of Baisaran near Pahalgam in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, armed militants opened fire on tourists with automatic weapons. At least 26 people were killed and more than a dozen injured. The assault heightened tensions between Islamabad and New Delhi—both vying for sovereignty over the turbulent Himalayan territory that has never known peace since partition from Britain in the 1950s.

As news spread—marking India’s most lethal attack since the 2008 Mumbai strikes—social media and television buzzed. A message circulated on Telegram claimed responsibility by an unknown militant faction called the “Resistance Front,” even as the shooters fled from nearby forests, unapprehended.

These militants, advocating for Kashmir’s secession from India, had largely avoided targeting tourists in recent years. The Pahalgam attack changed that. It reignited discussion about active separatist armed outfits, accused by India of being backed by Pakistan, and opposed to Delhi’s control over most of Kashmir—fighters who view Indian rule as an occupying force that must be resisted.

In this series of articles, we explore this armed group and the major attacks it has taken responsibility for or been blamed for. We’ll also delve into other militant organizations active on both sides of Kashmir, examine their strategies against Indian rule, and assess their role in fueling tensions between the nuclear neighbors.

Roots of the Armed Rebellion

The Kashmir insurgency has driven decades of India–Pakistan discord. Militant violence surged after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, as foreign mujahideen funneled into the region.

The insurgent narrative in Kashmir emerged in two waves: public frustration with Delhi in the 1980s, which gave rise to Pakistan-backed groups from the early ’90s; and a more recent, though still significant, decline in violence.

The insurgency’s roots are entwined with demands for local autonomy. Kashmir experienced limited democratic development until the late 1970s. By 1988, expanding Indian-led reforms restricted legitimate avenues for dissent, driving many toward armed separatism.

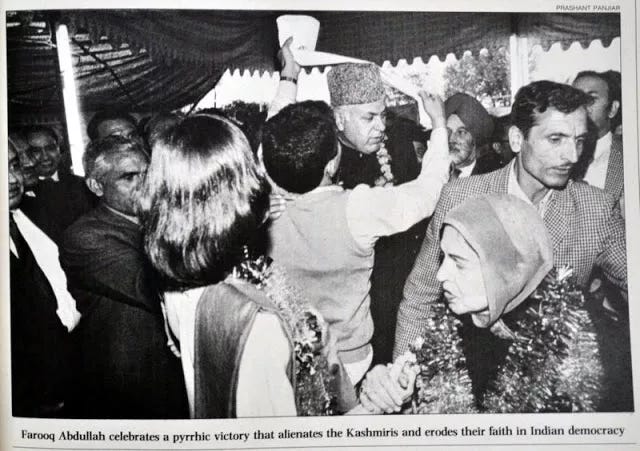

After the disputed 1987 Jammu and Kashmir state elections—believed to be rigged in favor of Farooq Abdullah’s alliance with the Indian National Congress—faith in Indian democracy crumbled. Prominent separatist voices like the Islamic Jamhoor and Peoples’ Conference, members of the state assembly, filled the cauldron of resistance.

Summer of 1988 marked the insurgency’s public emergence—with protests, strikes, and targeted attacks evolving into India’s most pressing security crisis in the 1990s.

By late 1989, the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) escalated assassinations of suspected Indian spies and collaborators, assassinating over 100 officials in six months to disrupt governance.

In response, India imposed the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) in September 1990, granting sweeping authority to security forces to arrest and detain suspects without warrants—a controversial move that hardened Delhi’s response.

Under JKLF leaders like Ashfaq Majid Wani, Yasin Bhat, Hamid Sheikh, and Javed Mir, several new militant factions—such as the Tigers of Allah, Peoples’ League, and Jamaat-e-Islami—emerged. Indian media began linking these groups exclusively to Pakistan.

Security expert Paul Kapur argues in Jihad as Grand Strategy that Kashmiri unrest was primarily driven by chronic mismanagement by India’s central government, not by Pakistan . India, however, consistently accuses Pakistan’s intelligence agencies of arming and training these militants—a charge Islamabad denies, stating it only offers diplomatic and moral support in light of historic conflict.

Pakistan historically viewed militant proxies in Kashmir and Afghanistan—especially during the Soviet withdrawal—as a strategic success. But starting in 2004, Pakistan began withdrawing its militant support, especially after two assassination attempts on President Pervez Musharraf. His successor, Asif Ali Zardari, labeled Kashmiri militants “terrorists,” though the extent of Pakistan’s intelligence rollback remains unclear.

While the insurgency became chiefly homegrown over time, India maintained a heavy military presence along the Line of Control, triggering large-scale protests. Estimates by the Jammu & Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society cite around 70,000 deaths—mostly civilians—at Indian hands, with other NGOs pushing the figure closer to 80,000, including militants and security forces. Districts most affected include Kupwara, Baramulla, Poonch, Doda, Anantnag, and Pulwama.

Violence peaked in the 1990s and early 2000s, then steadily declined from 2004 to 2014. A 2006 Human Rights Watch report stated at least 20,000 civilians had been killed in the conflict by then—figure which probably undercounts—and the territory had seen 7,000 insurgency-related incidents by March 2017 .

The Indian Home Ministry recorded the lowest number of violent incidents in 2008—a 20-year low of 700, a 40% drop from 2007. That year also marked the first time civilian casualties fell below 100 since 1990 .

Though militants were active on both sides of the Line of Control, overall violence in Kashmir significantly declined. Influence of groups like Hizb-ul-Mujahideen—many of its fighters having experienced combat under Gulbuddin Hekmatyar in ’90s Afghanistan—waned.

Beyond political parties pursuing electoral means, other groups have chosen armed struggle. Their objectives vary: some advocate pro-India, some for accession to Pakistan, and a third seek full independence.

The militant scene is a shifting mosaic—groups morph, merge, rebrand, and may share fighters.

Resistance Front — the Newcomer

Emerging in response to India’s abrogation of Article 370—which revoked Kashmir’s autonomy and reorganized it into federally controlled union territories—the group opposes new residency and property rights for non-Kashmiris, which are perceived as demographic engineering.

Though not well-known before the Pahalgam attack, its Telegram statement warned of violence against illegal settlers. Militarily, the Resistance Front draws on traditional tactics from mountain hideouts, maintaining anonymity while escalating the impact of their violent strikes.

The un-Islamic-neutral name “Resistance Front” signals a shift from traditional religious branding toward Kashmiri nationalism.

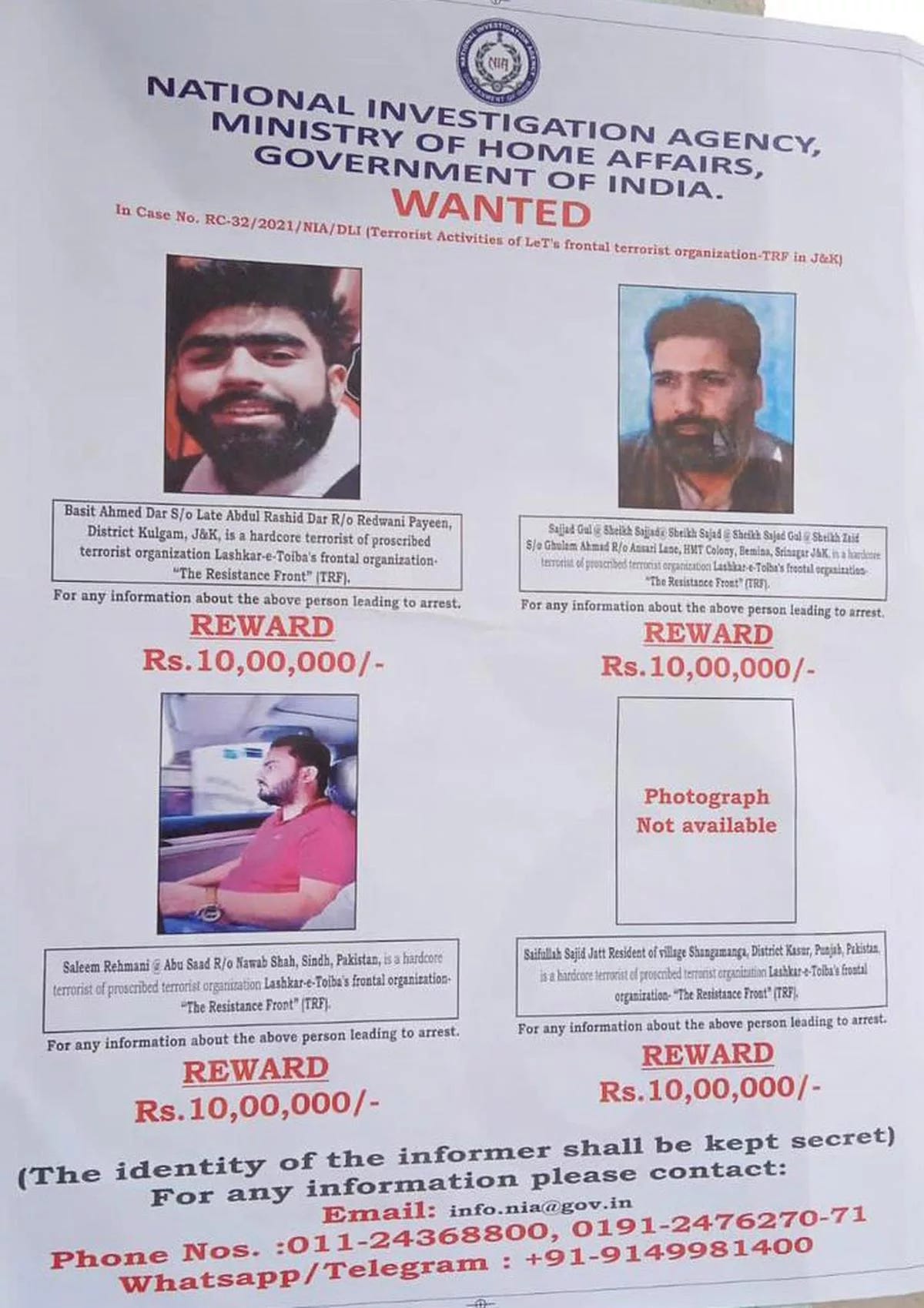

The Indian government claims the group is a front for Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba, accusing Islamabad of supporting the rebellion, a charge Pakistan vehemently denies while calling for a neutral inquiry.

Since 2020, the Resistance Front has taken responsibility for civilian, security, and political target attacks —including listing Kashmiri journalists on “traitors’ hit lists”—prompting some to resign . In January 2023, India designated it a terrorist organization, citing recruitment and cross-border arms smuggling.

Its founder, Sheikh Sajad Gul (aka Sajad Ahmed Sheikh), allegedly the mastermind behind the recent attack, was put on India’s terrorist watchlist.

Lashkar-e-Taiba — the Charitable Front

Fortified in the early ’90s by Hafiz Mohammad Saeed through his charitable Da’wah Centers, Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) became the most formidable armed group in Kashmir. Its attacks extend beyond Kashmir—striking the Indian Parliament in 2001, Mumbai trains in 2006 (killing 189), and the 2008 Mumbai shootings (166 deaths) .

Since 2002 Pakistan has banned LeT and Da’wah, and the UN and U.S. list them as terror organizations. Yet critics argue the group operates under charitable fronts and maintains a strong presence. After the 2019 Pulwama attack, Pakistan reinstated the ban and arrested Saeed, sentencing him in 2019.

On May 7, 2025, India launched missile strikes on Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, targeting Da’wah’s compound—accusing it of funneling militants trained by Pakistan's ISI . Islamabad denies India's normalizing pressure is justified, but the group remains central to India's narrative of terror threats.

Analyst Ashley Tellis noted in Carnegie, “From the beginning, Lashkar‑e‑Taiba became a preferred wing of the Pakistani state … for local ambitions and for keeping India off‑balance.” Islamabad’s tolerance for LeT, even after Saeed’s arrest, casts doubt on its assurances.

Founded in 1989 by Muhammad Ahsan Dar and led by Syed Salahuddin, this native Kashmiri group once dominated the 1990s. It seeks Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan and was trained in Afghan camps allied with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Internal strife, including a failed 2003 ceasefire by Abdul Majid Dar and his subsequent assassination, diminished its strength. Now it survives only in scattered high-altitude hideouts.

Ansars, later Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen, supposedly executed Kashmir’s first “terrorist act” in 1995 by abducting Western tourists, resulting in a U.S. ban. They also hijacked a passenger plane in 1999. Though part of Pakistan’s madrassah networks and allegedly tainted with Al-Qaeda alliances, declining support from Pakistani institutions has weakened them.

Founded by Masood Azhar post-release in 2000, Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) clashed with India’s Parliament in 2001, attacked civilian targets, and is UN-designated. India asserts it remains active in Pakistan’s Bahawalpur region and continues to receive Al-Qaeda links.

Azhar has kept a low profile, but a local Deobandi seminary in Bahawalpur, “Sabhan Allah Center,” allegedly allied with him, has been targeted in Indian strikes.

While Al-Qaeda’s direct presence in Kashmir is unclear, many fighters have undergone training in Taliban and Al‑Qaeda-linked madrassas. JeM’s Masood Azhar is suspected of funding ties to Osama bin Laden .

Former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and U.S. sources say Al-Qaeda had a “Kashmir wing” in 2002, and in 2006, Al-Qaeda declared one—supported by senior U.S. officials .

A Major Obstacle to Peace

Numerous less prominent but dangerous groups also operate in northern Pakistan and Punjab, including Turkistan Batani, Pakistani Taliban, Gul Bahadur Group, and elements of the Haqqani network.

Sectarian militant outfits, such as anti-Shia militias that target Hazara Shias in Balochistan, further complicate the landscape. New factions like the “Kashmir Salvation Movement,” “Force for Freedom,” and “Farzandān-i-Millat” have emerged. The moderate All Parties Hurriyat Conference often mediates between Delhi and insurgents.

Despite bans, these groups often rebrand to evade detection. Alleged amalgams like Lashkar Omar—comprising JeM, LeT, and hardline groups including Lashkar-e-Jhangvi—persevere. Pakistani intelligence has reportedly “lost control” of some caches, which now conduct attacks within Pakistan itself .

Even amid restrained peace talks resumed in 2004, cross-border militant infiltrations continue to derail sustainable resolutions. The historic 2005 bus service link and dialogue efforts collapsed following the 2008 Mumbai attacks—widely blamed on Pakistan’s ISI.

Kashmir remains a geopolitical flashpoint bedeviling India–Pakistan relations, with mutual allegations of human rights abuses sowing enduring mistrust.