This year’s March of Return in the 1948-occupied territories, which was scheduled to head to the village of Kafr Sabt, was canceled after the Israeli government deliberately placed numerous obstacles before the organizers, ultimately forcing them to call it off.

Kafr Sabt is a depopulated village located in the district of Tiberias. It is one of four Maghrebi villages situated west of the city in the area known as “Shafa Tiberias,” which overlooks the Jordan Valley. These four villages were collectively known as “Bilad al-Amir” (The Prince’s Land).

Before the Nakba of 1948, there were about eleven villages inhabited by Palestinians of Maghrebi descent, particularly Algerians, broadly referred to as “Maghrebis” from North Africa. These villages were located in the districts of Safad and Tiberias.

Safad was home to five villages: Dishum, Amuqa, Marus, Talil, and al-Husayniyya. Tiberias had another five: Samakh, Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt. The eleventh village, Husha and Kusayr, was located in the district of Haifa.

In addition to rural settlements, Maghrebi migrants also settled in neighborhoods in major Palestinian cities like Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Acre. The Moroccan Quarter in Jerusalem’s Old City, in particular, was among the most renowned and historic neighborhoods before it was demolished by the Israeli army following its occupation of the city in 1967.

As for the eleven villages, all were depopulated in 1948, except for Sha‘ara—one of the four villages of “Bilad al-Amir”—which had been uprooted and depopulated in the 1920s, before the Nakba. However, the historical presence of Algerian migrants in Palestine predates these events, with roots going back to the Crusades and what can be termed a “narrative of pilgrimage and protest.”

Pilgrimage and Protest

In his recently translated book Under the Shadow of the Wall: The Moroccan Quarter in Jerusalem, Its Life and Death 1178–1967, French historian Vincent Lemire traces the deep history of Maghrebi presence in Jerusalem through the evolution of the Moroccan Quarter, a symbolic space reflecting the broader Maghrebi legacy in the Levant.

Lemire begins with the origins of the quarter to highlight the story of mass migration from the Maghreb to Palestine at the end of the 12th century, triggered by the Crusader occupation and the establishment of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

He explains that Maghrebi migration to the East followed two intertwined paths. The first was the pilgrimage route to the holy sites, with Jerusalem and Palestine occupying a central place in Maghrebi religious consciousness.

The second path was a response to the call for jihad against the Crusaders, as these migrations evolved into organized military mobilizations, answering Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi’s (Saladin’s) invitation to join his army in the liberation wars of the late 11th century.

Relying on Arab and foreign sources, Lemire recounts that in the late 12th century, Salah al-Din collaborated with his close Andalusian Sufi companion Sidi Abu Madyan and, under the initiative of his eldest son, Emir al-Afdal Ali, launched a series of charitable endowments in Jerusalem. These institutions aimed to house and care for pilgrims and fighters arriving from the Maghreb.

One of these was the Zawiya of Sidi Boumediene, established in the early 14th century, which became the nucleus of the Moroccan Quarter. Maghrebis had already been arriving in Jerusalem for over 150 years. The famed Andalusian Sufi Ibn Arabi, during his 1206 visit, noted their high status, saying they “worked miracles defending Muslims.”

Until the Nakba, the village of Ein Karem, located west of Jerusalem, was endowed to the Zawiya and the Quarter’s charitable institutions for nearly 700 years.

The Maghrebi pilgrimage to the Levant and Palestine continued unbroken from the establishment of the Zawiya until the mid-19th century, when the Shadhili-Yashruti zawiya was established in Acre in 1868, after its Tunisian founder Sheikh Ali Nour al-Din al-Yashruti arrived in 1850.

In addition to religious functions, the Maghrebi presence also held military significance. Sources note their participation in various conflicts, particularly during the era of Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani (1695–1775), who rebuilt Acre and enlisted Maghrebis to guard and fortify it.

In Jerusalem as well, Lemire notes that the Moroccan Quarter’s residents were tasked with guarding the city’s gates, a testament to their respected role in the city’s security and society.

Yet, the most significant wave of Maghrebi—particularly Algerian—migration to Palestine occurred in the mid-19th century, following the exile of Emir Abdelkader al-Jazairi to the Levant after his forced departure from Algeria under French colonial pressure.

In the Emir’s Footsteps

Algerian migration to the Levant followed the path laid by Emir Abdelkader, who arrived in Damascus from Algeria via the Port of Beirut in 1856. But the Emir had already been preceded by Sheikh Ali Nour al-Din al-Yashruti, founder of the Shadhili-Yashruti zawiya, who settled on the Palestinian coast in 1850, according to Suhail Khalidi’s book Maghrebi Radiance in the Levant: The Role of the Algerian Community in the Levant.

The Emir’s 1847 defeat forced him into exile after signing a “safe conduct” agreement with the French. This marked the start of the first wave of Algerian migration to the Levant (1847–1858), spearheaded by Rahmaniyya Sufi sheikhs.

Among the most notable was Sheikh Ahmad al-Tayyib bin Salim, who arrived in Beirut with 560 Algerians and then moved to Damascus. According to Abdullah Salah Maghrebi in From Djurdjura to Mount Carmel: The Migration and Identity Experience of the Abdul Rahman Maghrebi Family, these migrants became the nucleus of the Maghrebi presence in rural areas of Safad and Tiberias, anchoring the Algerian identity in the Palestinian landscape.

Subsequent migrations occurred in three more waves identified by Palestinian historian Mustafa Abbasi in his research article The Algerian Community in the Galilee from the Late Ottoman Period to 1948. The second wave (1860–1883), the third (1883–1900), and the fourth (1900–1920) were driven by religious, political, economic, and security motives—all rooted in the French colonization of Algeria, beginning in 1830.

A key catalyst was the suppression of Emir Abdelkader’s revolt in the 1840s. Later waves reacted to the oppressive policies of the French regime, including mandatory conscription imposed during World War I, which directly sparked the fourth wave.

Settlement and Its Motivations

The settlement of Algerian families in Palestine, particularly in the Galilee, dates back to the 1860s, with most settling in the rural areas of Safad and Tiberias. The settlement in Safad preceded that in Tiberias.

In The Claim of Dispossession: Jewish Settlements and the Arabs, Israeli historian Aryeh L. Avneri recounts a pivotal 1868 incident when Jewish settlers tried to establish a colony on the land of the village of Talil on the edge of Lake Hula. They were met with fierce resistance from recently arrived Algerian Maghrebi inhabitants. According to Suhail Khalidi in Maghrebi Radiance in the Levant, the villagers repelled the settlers with direct intervention from Emir Abdelkader.

Settlement in the Tiberias countryside began around 1870, when Algerians settled in five villages, starting with Samakh, located south of the city and the lake. The other four were west of the city, in the area known as “Shafa,” overlooking Tiberias from the west at the eastern edge of the Jezreel Valley.

According to Khalidi, the settlement of Algerian Maghrebis in the Galilee, and particularly in Tiberias, followed a coordinated plan overseen by Emir Abdelkader himself. The aim was to secure trade routes that passed through water corridors from coastal Acre to the inland cities of Safad and Tiberias, where the lakes of Tiberias and Hula were located.

Khalidi emphasizes this strategic goal by noting the simultaneous settlement of Algerian families in the Hauran region of southern Syria, in villages such as Kafr Sanj, Ghabaghib, Abidin, and al-Kuwayya.

Thus, the Maghrebi villages in the Galilee became geographically linked to the historic “Darb al-Hawarna” (Haurani Route), the grain trade path from Hauran, through Samakh and Tiberias, and up westward toward Shafa, where the four Maghrebi villages—Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt—were located.

These villages occupied key crossroads leading either westward via the “sea road” connecting Tiberias to the Port of Acre, or southwestward via Khan al-Tujjar (Caravansary of Merchants) or “Uyoun al-Tujjar” (Merchants’ Springs) toward the Jezreel Valley, and on to the southern Palestinian coast.

Another account offers a different explanation for the resettlement of Algerians in the Galilee. Beginning in the 1860s, Ottoman authorities reportedly grew uneasy about the growing number of Maghrebis clustering around Emir Abdelkader in Damascus, who had become a powerful local leader, especially after his pivotal role in protecting the city’s Christians during the 1860 massacres.

Fearing his influence, the Ottoman state began redistributing his followers across southern Syria and northern Palestine, using them as a security force to protect trade routes and control Bedouin tribes.

Accordingly, Palestinian historian Shukri Arraf states in The Bedouins of Marj Ibn Amer and the Galileans: Past and Present that the settlement of Algerian Maghrebis in the four villages—Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt—in Shafa Tiberias aimed to contain the nomadic tribes of Sbeih and Saqr in the Jezreel Valley, known for seasonal raids on the crops of Tiberias district villages such as Lubya and Hittin.

This version of history remained embedded in the oral memory of the Bedouin of Arab al-Shibli village, who would say: “The Turks brought the Maghrebis to hold back the Sbeih and Saqr Bedouin.”

The four Maghrebi villages came to be known as “Bilad al-Amir” (The Prince’s Land), in reference to Emir Ali ibn Abdelkader al-Jazairi, the son of Emir Abdelkader, who was appointed to oversee these villages and their lands, according to Suhail Khalidi.

The Ottoman state granted these lands to Algerian migrants, gave them an eight-year tax exemption, and exempted them from military service for twenty years to encourage stability.

Emir Ali lived in the village of Ulam, where he built a grand home known as “the Emir’s Palace.” In a recorded interview published on the Palestine Remembered website, Hajj Saleh Ali proudly recounts, “We had a spacious house called the Emir’s Palace…”

The house was built in the late 19th century and stood until the Nakba, when it was demolished along with the rest of the village. However, its legacy remained in the popular memory of the region, echoed in folkloric chants of the farmers of the Jezreel Valley, including the well-known line: “Call upon the prince of the Arabs… to the horses and horsemen…”

In Residence and Naming

The Maghrebi migrants settled in the villages of Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt, but they did not found these villages. The villages had long existed with their original names and were vacant prior to the Algerians’ arrival. Historians suggest the depopulation occurred due to the instability that followed the withdrawal of Egyptian forces in 1840, prompting many peasants to abandon their villages.

Historian Shukri Arraf estimates in an unpublished paper on Kafr Sabt that the village was deserted for 15–20 years before the Algerians settled it, a timeline that likely applies to the other three villages. The four became collectively known as “Bilad al-Amir” by the early 1870s.

According to From Djurdjura to Mount Carmel, the Algerian families who settled in Shafa Tiberias descended from the tribes of Wadi al-Bardi and Bouira in Algeria. They spread across the four villages: Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt—each name predating their arrival and cited in historical travelogues.

Ulam, in particular, is an ancient Roman-era name. It appears in various sources as “Ulam,” “Ulam,” and “Awalem,” though its meaning and origin remain unclear. Even among locals of Algerian descent, the name’s etymology is unknown, as noted in interviews with Hussein Hammadeh and Saleh Ali: “We arrived and found it was called Ulam…”

Ma’dhar also carries an old name. Historian Walid Khalidi notes in All That Remains that it was known as “Kafr Matar” during the Crusader era. One local story recounted by Hajj Muhammad Nahar al-Mashraqi says the name Ma’dhar derived from being a place where horses were let loose to graze freely, evoking a rural sense of fertility and openness.

Sha‘ara’s name, however, has no known etymology, with no sources explaining its origin. As for Kafr Sabt, its accurate pronunciation is Kafr Sibt (with a short “i”), and it was mentioned in Crusader records as “Kefar-set,” likely its original Arabic name. The French explorer Pierre Jacotin recorded it as “Kafr el-Sitt” in his 1799 map, while French traveler Victor Guérin referenced a rock-hewn olive press there during his 1875 visit.

In the Location and Topography of Each Village

The four villages of Bilad al-Amir were located across the Shafa area, adjacent to the city of Tiberias and its valley. A series of descending slopes separated them from the city, with Shafa situated roughly 10 to 11 kilometers west of Tiberias. The four villages stretched from Wadi al-Bira in the south, where Ulam was located, to the Maskana–Golani junction in the north, where Kafr Sabt stood.

Other villages populated by local residents also existed in the Shafa area, such as Sirin, while others, like al-Haditha and Kafr Kama (a Circassian village resettled during the same period as the Algerian migrants), lay between the villages of Bilad al-Amir.

Awlam was situated along the slopes of Wadi Awlam, which flowed westward into Wadi al-Bira. To the east, in the valley, lay the village of al-Dalhamiyya; to the south, Sirin; and to the northwest, Ma’dhar. Ulam covered approximately 18,546 dunams of land and had around 850 residents before the Nakba.

According to Abdullah Maghrebi in From Djurdjura to Mount Carmel, most Algerian migrants who settled in Ulam were fighters in Emir Abdelkader’s resistance against French colonization. This may explain the Emir’s decision to establish his palace there.

Ma’dhar stood on a high hill, about 6 kilometers from Mount Tabor to the north and roughly 12 kilometers from Tiberias. Southeast of it was Ulam. A dirt road linked Ma’dhar to the nearby Circassian village of Kafr Kama to the northwest.

Several springs in Ma’dhar fed Wadi al-Bira, which flowed eastward into the Jordan River. According to Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains, the village spanned 4,579 dunams in 1945 and had a population of around 500 by the time of the Nakba.

Sha‘ara, due to its proximity and location, was considered a twin village to Kafr Sabt. It lay 11 kilometers west of Tiberias, bordered by Kafr Sabt to the north and Kafr Kama to the south. To its northwest, more than 5 kilometers away, was the depopulated village of al-Shajara.

Sha‘ara does not appear on British Mandate maps, as its population was displaced and its structures demolished in the 1920s, making information about it scarcer than for the other villages of Bilad al-Amir.

Kafr Sabt was located north of Sha‘ara and Kafr Kama, about 10–11 kilometers west of Tiberias. To the north lay the depopulated village of Lubya, separated from Kafr Sabt by the road from Tiberias to the Maskana junction and onward to the Acre-bound coastal road. West of Kafr Sabt were the lands of al-Shajara, less than 5 kilometers away.

Walid Khalidi estimated that Kafr Sabt encompassed 9,850 dunams. Beginning in the early 1930s, parts of this land were gradually transferred to Jewish ownership, eventually totaling nearly half of the village’s area. The village had a population of 450–500 until 1948.

Between Integration and Social Distinction

The four villages of Bilad al-Amir—Awlam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt—are remembered in recent memory as Maghrebi villages and were perceived as such by Galilee residents. Yet this does not mean they were purely Maghrebi in population. Local Arab families also lived in them, and Bedouin tribes such as the Dalaika and al-Mashariqa settled at their outskirts.

These Bedouins were part of the community—they sent their children to village schools, buried their dead in village cemeteries, and drank from the same springs.

Hajj Muhammad Nahar al-Mashraqi, born in 1910 in Kafr Sabt and interviewed for Palestine Remembered, considered himself and his tribe as native to the village, though they were part of the al-Mashariqa Bedouin, not Maghrebi migrants. The term “Mashariqa” (Easterners) was used to distinguish them from the “Magharibah” (Westerners) who came from Algeria.

In his interview, al-Mashraqi recounts his clan’s hardship after being expelled from Kafr Sabt’s vicinity by British Mandate authorities in the 1930s, following the sale of some of the village’s land to Jewish buyers. They were forced to relocate to nearby Ma’dhar, which came to be associated with them.

Thus, the local Palestinian Arab presence in these villages never entirely disappeared, despite their Maghrebi identity. The Maghrebi migrants reshaped their identity from the 1870s until the Nakba of 1948.

In a recorded interview by the “Zochrot” Association, which documents Nakba memory in historic Palestine, Hajj Mahmoud Saleh Abdul Qadir Issa, a native of Kafr Sabt, recalls how his Algerian ancestors’ traditional dress initially attracted curiosity and ridicule from locals.

“When we first came, we wore barnous cloaks, and people thought we were poor and mocked us,” he said—highlighting the cultural distinctions that led to early social tension with nearby villagers.

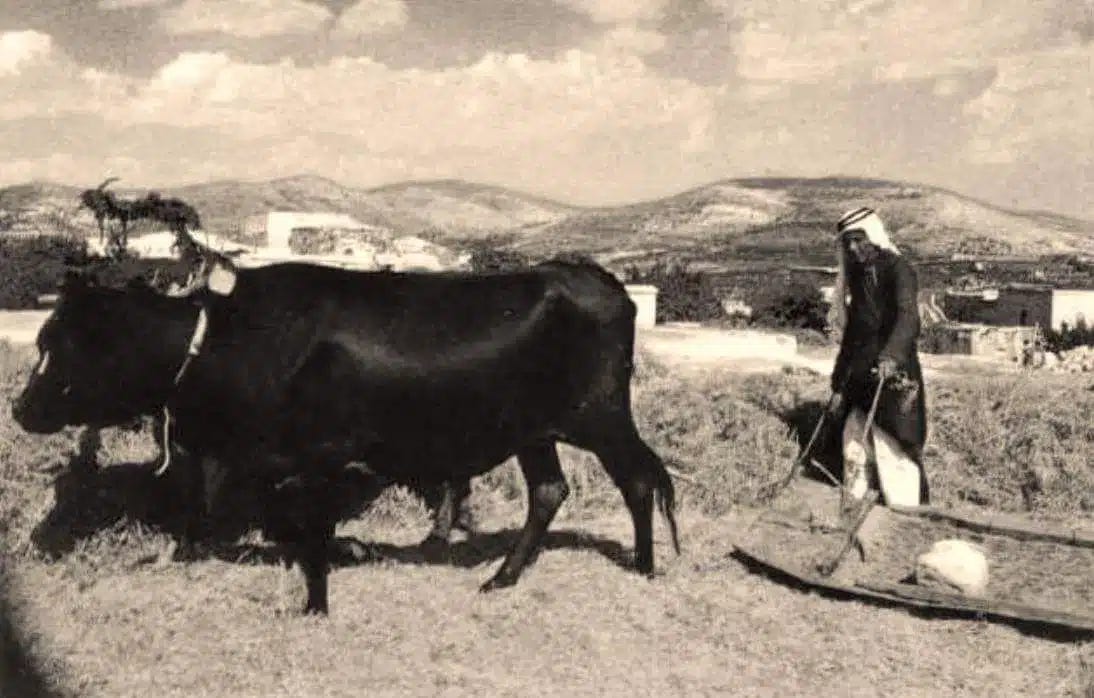

Over time, however, these differences faded. The Algerian migrants in Ulam, Ma’dhar, Sha‘ara, and Kafr Sabt began assimilating into the broader Arab-Palestinian environment, adopting local agricultural practices. Farming was their primary livelihood, like other peasant communities in the Tiberias countryside.

Gradually, the Algerians adopted local customs in clothing, replacing the barnous with the Levantine qambaz, and also adapted local styles in song, cuisine, marriage rituals, and daily life. Intermarriage with local families in nearby villages like al-Haditha, Sirin, al-Shajara, and Lubya further cemented their integration.

Conversely, the Algerians influenced local culture as well—especially culinary traditions. One of the most enduring legacies is the dish maftoul, also known as couscous in the Maghreb, which found its way into Palestinian and broader Levantine cuisine. In the Galilee, the dish is still colloquially called “al-Maghribiyya,” reflecting its origins.

Interestingly, as Ahmad al-Maghribi, a displaced native of Kafr Sabt, explains in a filmed interview for the “Return” series on YouTube, villagers didn’t call the dish maftoul or Maghribiyya, but simply “al-ta‘am”—“the food”—often pronounced with a softened “t.” It was the centerpiece of feasts and social gatherings.

Some Maghrebi-influenced songs also found their way into local tradition. One popular tune, “Mandil ya Kareem al-Gharbi… Mandil w’mdayya‘ darbi…” references the practice of using a mandil (scarf) in folk fortune-telling—a role often filled by Maghrebi women at the time.

Overall, while the people of Bilad al-Amir remained known for their Algerian–Maghrebi roots, they gradually became “Mashriqized,” fully integrated into the socio-cultural fabric of Tiberias and the Galilee from the time of their arrival.

They also participated in political and resistance movements—first against Ottoman conscription during World War I, and later against British Mandate policies, especially the sale of lands to the Zionist movement, which targeted the villages of Bilad al-Amir. Sha‘ara was the first among them to fall victim.

The Nakba Came Early in Sha‘ara

British survey maps of Galilee and the Tiberias countryside from the 1920s make no mention of Sha‘ara. Unlike the other villages, whose lands were gradually transferred to Jewish ownership, Sha‘ara was sold in its entirety—land and homes alike—leading to the forced expulsion of its residents and the complete leveling of the village between 1926 and 1927.

Sha‘ara was the only one of the four Bilad al-Amir villages to be depopulated in the 1920s. Yet it was not the only village in the Jezreel Valley uprooted at the time. Multiple villages were sold to Zionists through land deals involving powerful feudal families, some based in Lebanon and Damascus, others Palestinian families from Nazareth and Haifa. This marked the so-called “early Nakba,” predating the mass expulsions of 1948.

Sha‘ara’s lands, originally owned by descendants of Emir Abdelkader—the Algerian family—were allegedly sold by Prince Sa’id bin Ali bin Abdelkader, according to both Arab and Hebrew sources cited in The Claim of Dispossession. However, Suhail Khalidi refutes this in Maghrebi Radiance, blaming his son, Abdul Razzaq, instead—calling the sale a “black stain” on the family’s legacy.

Khalidi also recounts that Sha‘ara’s residents—primarily the Awlad Sidi Issa family, originally from Sour al-Ghozlan in Algeria—refused to sell their land, resisted expulsion, and even forced Abdul Razzaq to leave the village. They rejected his offer of alternative land in Hauran and initially remained in caves and rock shelters around Shafa until they were ultimately forced to relocate to the Maghrebi village of Abidin in Hauran.

Finally, land sales to Zionist groups during the 1920s and 1930s also affected the other three villages—Ulam, Ma’dhar, and Kafr Sabt—gradually transferring more than half their lands. However, this process did not displace the population until the Nakba of 1948, when the villages of Bilad al-Amir, along with the rest of Tiberias district and the city itself, were uprooted.

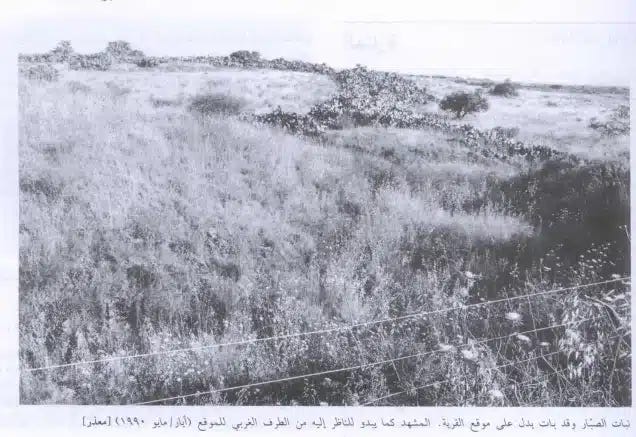

In May 1948, Ulam and Ma’dhar were occupied by the Golani Brigade and fell officially on May 12. Kafr Sabt was seized in early July 1948 by Zionist militias in preparation for the capture of nearby Lubya during that phase of military operations.