Nestled on the northern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains, Chechnya occupies a strategic yet precarious position, bordered by Dagestan to the north and east, Ingushetia and North Ossetia to the west, and Georgia to the south. This geography has subjected it to relentless Russian influence, leaving its 1.5 million inhabitants—according to the 2021 census—deeply affected by ongoing conflicts and wars.

The republic's terrain transitions from mountainous regions in the south to rolling plains in the north. Approximately 170 clans inhabit Chechnya, with over half residing in the highlands and the remainder in the plains between the Sunzha River and the northern face of the Caucasus Mountains.

Chechens constitute 96.4% of the population. The Terek River, originating from the Caucasus glaciers and flowing into the Caspian Sea, is the region's primary waterway.

This article is part of the “Islamic Lands in Russia” series, which delves into the histories of Siberia and the North Caucasus republics, including Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, Tatarstan, and Bashkortostan.

These regions, home to approximately 25 million people, are predominantly Muslim, mainly adhering to the Hanafi and Shafi'i Sunni schools. Shi'a Muslims, primarily of Azerbaijani and Tajik descent, are mostly found in Dagestan.

Each republic's social and religious characteristics, along with the challenges and turning points that have shaped their histories and positions in the world, are examined. The nature of their relationships with governing systems is also explored, all within the context of Russian influence.

Chechnya: Roots and Social Structure

Historical accounts trace the origins of the Chechens to the Nakh peoples, who have inhabited the Caucasus for millennia. Chechen society is notably cohesive, with relationships primarily based on familial and clan ties, which play a significant role in social justice matters.

The Chechen language, derived from the Nakh-Daghestanian family, was traditionally written using the Arabic script until the Soviet regime banned it in 1924, replacing it with the Cyrillic alphabet. Today, most Chechens are bilingual, speaking both Russian and Chechen.

Agriculture, sheep herding, and cattle farming are prevalent occupations among Chechens. Additionally, many engage in carpet weaving, textile production, and traditional crafts. Currently, oil production forms the backbone of Chechnya's economy, supplemented by minerals like iron, copper, and silver.

Despite financial support from the Russian federal budget, Chechnya ranks as the second poorest region in Russia, following Ingushetia, in terms of per capita GDP. Some Chechens advocate for the establishment of a free economic zone and a stake in a local oil company, but the Russian administration is unlikely to accommodate these demands.

The Spread of Islam

Initially pagan, the Chechens saw limited Christian influence from neighboring Georgia after the 10th century. However, due to Chechnya's rugged and remote landscape, Islam spread gradually, with significant expansion occurring in the 16th and 17th centuries, largely through Sufi missionaries. This Islamic influence played a crucial role in unifying the Chechens and much of the North Caucasus.

Chechen folklore, rich with proverbs, riddles, songs, and oral tales, serves as a vital repository of the nation's history and traditions. Stories of heroes, particularly during Imam Shamil's era, continue to inspire and shape Chechen cultural identity.

By preserving their language, traditions, and epics through generations, Chechens have withstood attempts at cultural assimilation and maintained their heritage despite Russian-imposed challenges. Traditional Chechen architecture, especially in mountainous areas, stands as a unique testament to their enduring culture.

Trials and Tribulations

The history of Chechen-Russian relations is marked by prolonged conflict. Russia's expansion into the Caucasus aimed to create a buffer zone against adversaries like the Ottomans and Persians, while also promoting Russian culture and Orthodoxy, necessitating the subjugation of the North Caucasus.

This centuries-long struggle can be delineated into several historical phases:

The First Russian Invasion

As Russia transitioned into an expansive empire, Islam was spreading widely in the Caucasus. In the early 16th century, a monk named Philotheus penned influential letters positioning Moscow as the "Third Rome," asserting that Russian tsars were the rightful heirs to Byzantium with a divine mission.

Following this ideology, Ivan IV declared himself Tsar in 1547 and launched campaigns against Muslim territories, capturing Kazan in 1552 and Astrakhan in 1556, thereby facilitating Russian access to the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus.

The first Russian incursion into Chechnya occurred during Ivan's reign, marked by brutal tactics and the construction of fortresses to assert control. However, these efforts were thwarted by resistance and conflicts with Persia. Subsequent attempts, including one by Tsar Boris Godunov in 1604, also failed, delaying Russian dominance in the region for nearly a century.

The Sons of Peter the Great and the Three Imams

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Caucasus became a battleground among Sunni Ottoman Turkey, Shi'a Iran, and Orthodox Christian Russia. Russia's ambitions intensified under Peter the Great, who, despite failing to conquer Chechnya in 1722, set the stage for future campaigns.

The diverse Islamic populations of the North Caucasus, united by their faith, posed significant challenges to Russian expansion. Russian writer Marlinsky lamented, "The Caucasus would be delightful if not for the plague, cholera, and Islam."

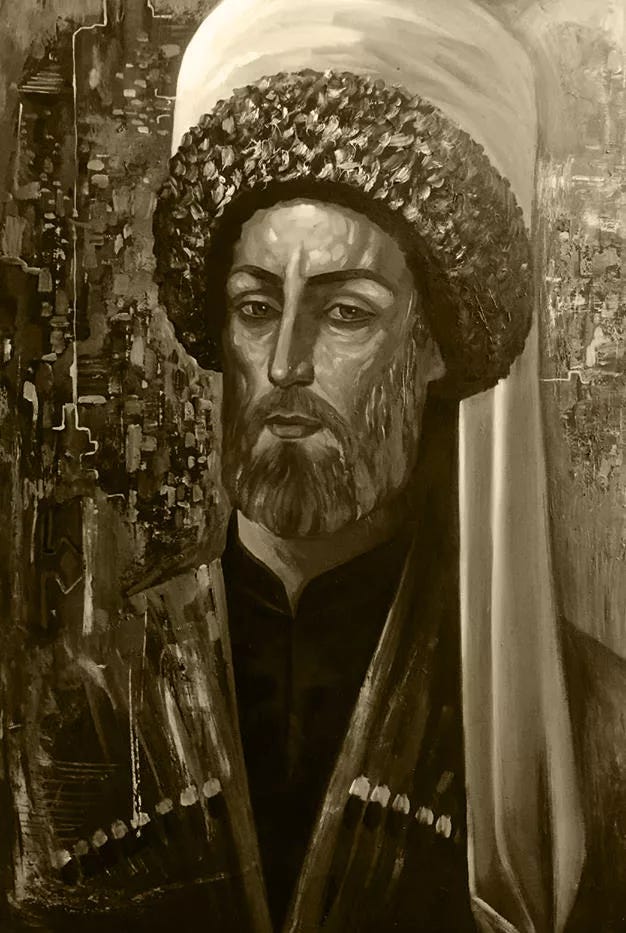

Key figures like Imams Mansur, Ghazi Mollah, and Shamil, all associated with the Naqshbandi Sufi order, emerged as leaders who effectively unified various Caucasian tribes against Russian forces, with the Chechens being particularly fervent in their resistance.

Imam Mansur: Rebuilding the Nation

Catherine the Great, ascending the throne in 1762, initiated extensive campaigns to expand Russian influence in the Caucasus. In 1777, Russian forces occupied parts of Chechnya, prompting fierce resistance led by Imam Mansur, a Naqshbandi Sufi and the first imam of Chechnya and the Caucasus.

Mansur's movement, grounded in Islamic ethics, achieved a significant victory in 1785 by defeating Russian troops along the Sunzha River. Despite being captured in 1791 during the defense of Anapa and dying in prison three years later, Mansur's efforts marked a critical chapter in Chechen resistance.

Yermolov: The Architect of Russian Terror

Recognizing the challenges of subduing Chechnya, Russia appointed General Alexei Yermolov as governor of the Caucasus in 1816. Yermolov employed ruthless tactics, including destroying villages, killing civilians, and establishing Russian settlements to suppress resistance.

In 1818, he founded the fortress of Grozny ("Terrible") on the Sunzha River, which became a symbol of Russian military presence and significantly hindered Chechen efforts for independence.

Ghazi Mollah: Unfulfilled Aspirations

Yermolov's brutal policies inadvertently strengthened the resistance, leading to the rise of Ghazi Mollah, an Avar scholar and Naqshbandi Sufi. Advocating for jihad and political freedom, Ghazi Mollah sought to unify the Caucasus but faced challenges in securing widespread allegiance.

Let me know if you'd like a more formal or literary version for editorial use.

Between 1829 and 1832, he achieved notable victories against Russian forces but was ultimately killed during the siege of his hometown, Gimry, in October 1832. His death, perceived as martyrdom, inspired continued resistance.

Imam Shamil: A String of Victories

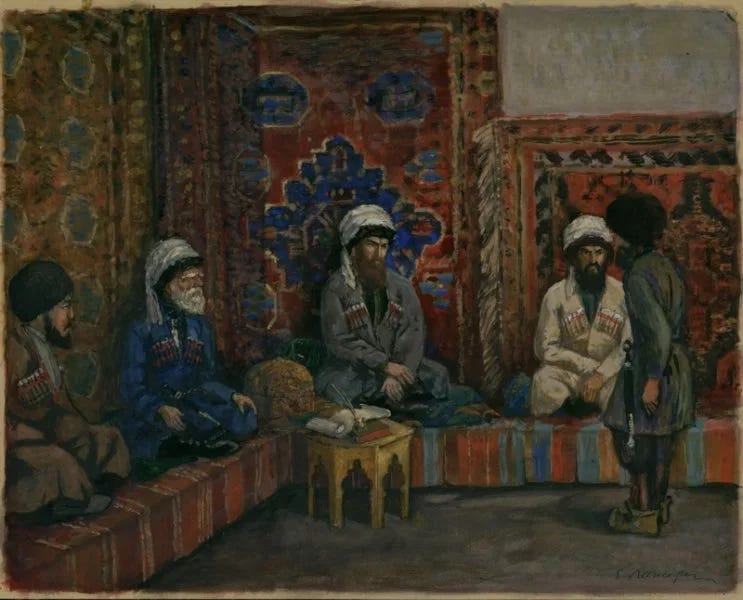

Shortly after the Battle of Gimry, Imam Shamil rose to prominence as the most renowned and inspirational of the three imams. Much like Imam Mansur half a century earlier, Shamil garnered widespread support among Chechens, who rallied around him as a symbol of steadfast resistance. His journey to Chechnya was likened by his followers to the Prophet Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina. From there, Shamil began uniting the Chechen clans under his leadership, just as he had done in his native Dagestan.

He succeeded in forming a political entity resembling a modern state within the territories under his control. With a combination of religious, political, and military reforms, Shamil led a disciplined and ideologically coherent resistance. He inflicted numerous defeats on Russian forces and reclaimed much of Dagestan and parts of Chechnya. By the end of 1843, he had established dominance over most of the northeastern Caucasus.

Shamil’s resilience and his ability to rally the North Caucasus tribes around the cause of Islamic governance made his 25-year resistance a historic epic. His leadership was founded on three principles: unification of the North Caucasus, expulsion of Russian forces, and the implementation of Islamic law. His movement gained traction across the region and achieved significant success during its peak.

Notably, Shamil lent his support to the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War (1853–1856), in which the Ottomans were engaged in battle with Russian forces. However, after the war ended, Russia intensified its pressure on Shamil.

General Yermolov’s failure to quell Shamil’s movement led the Russian Tsar to relieve him of command. A series of new generals took up the fight against Shamil, culminating in September 6, 1859, when Russian General Alexander Baryatinsky laid siege to Shamil’s fortress in Gunib with a 70,000-strong army.

In a brutal campaign led by Prince Mikhail Semyonovich, Russian forces systematically destroyed Chechen forests, villages, farmland, and livestock in an effort to starve out resistance fighters hiding in the mountains.

To protect women and children, Shamil entered into negotiations with the Russians. Though he was promised safe passage out of the country, he was placed under house arrest in Saint Petersburg for several years. After his capture, small pockets of resistance remained, but they gradually weakened.

With Shamil’s defeat, Russia was able to seize control of all Chechen territory by 1861. The aftermath included reprisals against Sufi clerics, the razing of Chechen villages, and a campaign of ethnic cleansing that saw thousands of Chechens forcibly exiled to the Ottoman Empire.

Three major factors contributed to the defeat of Shamil’s movement: the consolidation of Russian military power in the Caucasus following the Crimean War, the appointment of General Baryatinsky as commander-in-chief in the region, and internal divisions that gradually sapped the strength of the resistance.

Each phase of Chechen resistance ended with a reduced population due to forced migrations. For example, before Shamil’s war, around one million Chechens lived in the region. By the end of 1861, nearly 500,000 North Caucasians—including 81,000 of Shamil’s followers—had been exiled to Turkey.

Yet the Chechen spirit remained unbroken. When the Russo-Turkish War erupted in 1877, Chechens once again rose up in rebellion. Although it was quashed within a year, the Russian campaign of forced deportation continued, scattering Chechens to Turkey, Jordan, and Iraq. Despite Russian efforts to eradicate all signs of resistance, Chechens refused to surrender their struggle, unlike some Dagestani groups. The fight continued under new Sufi leaders.

The Fall of the Empire

In 1917, as the Bolshevik Revolution erupted, the Chechens and other peoples of the North Caucasus seized the moment to seek independence. A fresh revolt emerged under the leadership of the prominent religious figure Uzun Haji, who had long resisted tsarist Russia and had been imprisoned multiple times for his activism.

Uzun Haji aimed to unify the peoples of the Caucasus under a single banner. He made history by defeating the forces of General Denikin and declaring the formation of the “Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus” in April 1918, with formal recognition from Turkey.

The republic’s founding document, dated May 11, 1918, declared that it encompassed Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Dagestan, and Karachay-Cherkessia.

This was a rare moment of unity among the North Caucasian peoples, who collectively proclaimed independence from the Russian Empire. But the republic’s existence was short-lived. General Denikin opposed its creation, insisting on the indivisibility of Russia. In 1919, he launched a military campaign against Uzun Haji’s forces.

Even earlier, in February 1918, an agreement had been reached between the peoples of the North Caucasus and the Bolsheviks. It stipulated that Moscow would not interfere in the governance of the region in exchange for support in defeating the tsarist forces. But this promise was soon broken. When the Bolsheviks no longer needed the alliance, they reneged on their commitments.

By 1924, the Soviet leadership, particularly under Joseph Stalin, had decided to fully integrate the region into the USSR. Stalin dismantled the North Caucasus Republic and split its territories into smaller administrative units, ending the dream of a unified Caucasian entity.

As Soviet betrayal became apparent, Chechens once again rose in rebellion under the leadership of Said Bek, a descendant of Imam Shamil. His lineage gave credibility to the movement, and he led an armed resistance against the Red Army until May 1921.

In the years that followed, a succession of leaders carried on the fight. Rebellions broke out in 1922, 1924, 1925, 1928, and 1929, continuing well into the 1930s. During this extended period of turmoil, Chechen fighters repeatedly attacked railway lines, assassinated Red Army soldiers, and sabotaged Soviet oil installations—particularly those in Grozny.

Yet no event in the long and bloody history of Chechen-Russian relations left a deeper psychological scar than the mass deportation of the Chechens in the winter of 1944. The trauma of this forced displacement has endured across generations. It was only after Stalin’s death that Chechens were allowed to return to their homeland—and even now, the wounds of exile remain unhealed.

Here is the final major section of the translation, covering the post-Soviet period, the Chechen wars, and the contemporary era under Ramzan Kadyrov:

After the Soviet Era

By the 1980s, Chechnya was experiencing a religious revival. A new generation of Chechens was emerging—one that carried the inherited memory of Soviet oppression, ethnic cleansing, and religious persecution.

In 1991, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, former Soviet Air Force general Dzhokhar Dudayev led a successful bid to overthrow the Moscow-backed government in Chechnya. He won the presidency in democratic elections and took the oath of office while holding the Quran. After a series of referenda, Dudayev declared Chechnya's independence from both Russia and the now-defunct USSR.

Moscow, however, refused to recognize Chechen independence and launched the First Chechen War on December 11, 1994. Dudayev relocated the fight to the mountainous regions, where Chechen fighters—though fewer in number—proved to be highly effective. Their fierce resistance ultimately forced Russian troops to withdraw, and in August 1996, the Khasavyurt Accord was signed. This agreement effectively granted Chechnya de facto independence.

From 1996 to 1999, no major armed confrontations occurred between Russian and Chechen forces. Chechnya held free and fair elections and elected Aslan Maskhadov as president. The republic hoped to rebuild its institutions and economy after years of conflict.

However, the years of semi-independence were marred by lawlessness and widespread criminal activity. Moscow failed to provide any economic assistance or fulfill its reconstruction promises. Maskhadov’s administration was unable to assert full control, and various armed groups gained influence.

In 1999, Russia launched the Second Chechen War. This time, the Russian military was better prepared and more ruthless. Chechnya, economically devastated and militarily weakened, could not mount the same level of resistance. The brutal campaign ended with Russia regaining full control of Chechnya.

Strategic Silence

The two recent wars (1994–1996 and 1999–2000) devastated Chechnya. Tens of thousands were killed, the population declined sharply, and many Chechens fled abroad. A whole generation was raised in exile or amid the ruins of war.

Despite efforts to suppress memory and eliminate resistance, and despite Russian policies aimed at preventing any resurgence of separatism, Chechnya today remains under a rigid system of control.

The republic is now ruled by Ramzan Kadyrov, whose regime enforces a harsh and authoritarian order. Public expression is tightly restricted. Even the ruling elite lives in fear, lacking genuine legitimacy. Most Chechens see Kadyrov as “the lesser of two evils”—a man whose rule is tolerable only because Moscow’s alternatives could be far worse. The political climate remains grim, as oppressive as during the darkest periods of war.

On the religious front, however, the situation has improved significantly. Chechnya is experiencing a marked increase in religiosity. Every village has residents who teach the Quran and Arabic. Sufi traditions continue to dominate, though debates persist among political factions regarding the nature of the Islamization they seek. Salafism, however, is strictly prohibited.

In the end, Moscow’s approach today does more than echo the imperial past—it actively replicates its ideological framework. No matter what new arrangements are proposed to define relations between Chechnya and Russia, they remain constrained by the bitter memory of a long and painful history.