Egypt is home to one of the world’s richest archaeological legacies, a country whose heritage has been shaped by millennia of civilizations that flourished along the Nile, across its valleys, and deep into its deserts—east, west, and south. From Pharaonic to Greek, Roman, Coptic, and Islamic civilizations, the land of Egypt has borne witness to more than 5,000 years of human achievement, some scholars even suggesting longer spans of continuity.

This unparalleled civilizational wealth has positioned Egypt as a unique global repository of heritage—a cultural beacon that gathers the essence of humanity’s grandest traditions in one geographical locus. It has earned Egypt recognition as a cradle of civilization, attracting scholars and history enthusiasts from around the world.

Estimates on the number of Egypt’s historical sites vary. While one school of thought claims Egypt holds one-third of the world’s antiquities, this is challenged by UNESCO’s World Heritage list, which includes only six Egyptian sites out of 962 globally. Yet, the true significance of Egypt’s antiquities lies not merely in quantity but in the unrivaled historical depth and continuity they represent.

This immense value has made Egyptian antiquities a prime target for looters for centuries. Many treasures have been stolen—some through official documentation, others via illicit networks. According to Dr. Mohamed Al-Kahlawi, Secretary-General of the Union of Arab Archaeologists, nearly 30% of Egypt’s antiquities were stolen between 2011 and 2016 alone.

This long-standing pillage has fueled a thriving black market for antiquities, estimated at $20 billion annually—more than the combined revenues from the Suez Canal and tourism, Egypt’s two main sources of foreign currency.

This report, part of our “Plundered Heritage” series, explores Egypt’s archaeological wealth, the timeline and types of looting, the current whereabouts of these artifacts, and the state’s efforts to reclaim what has been lost.

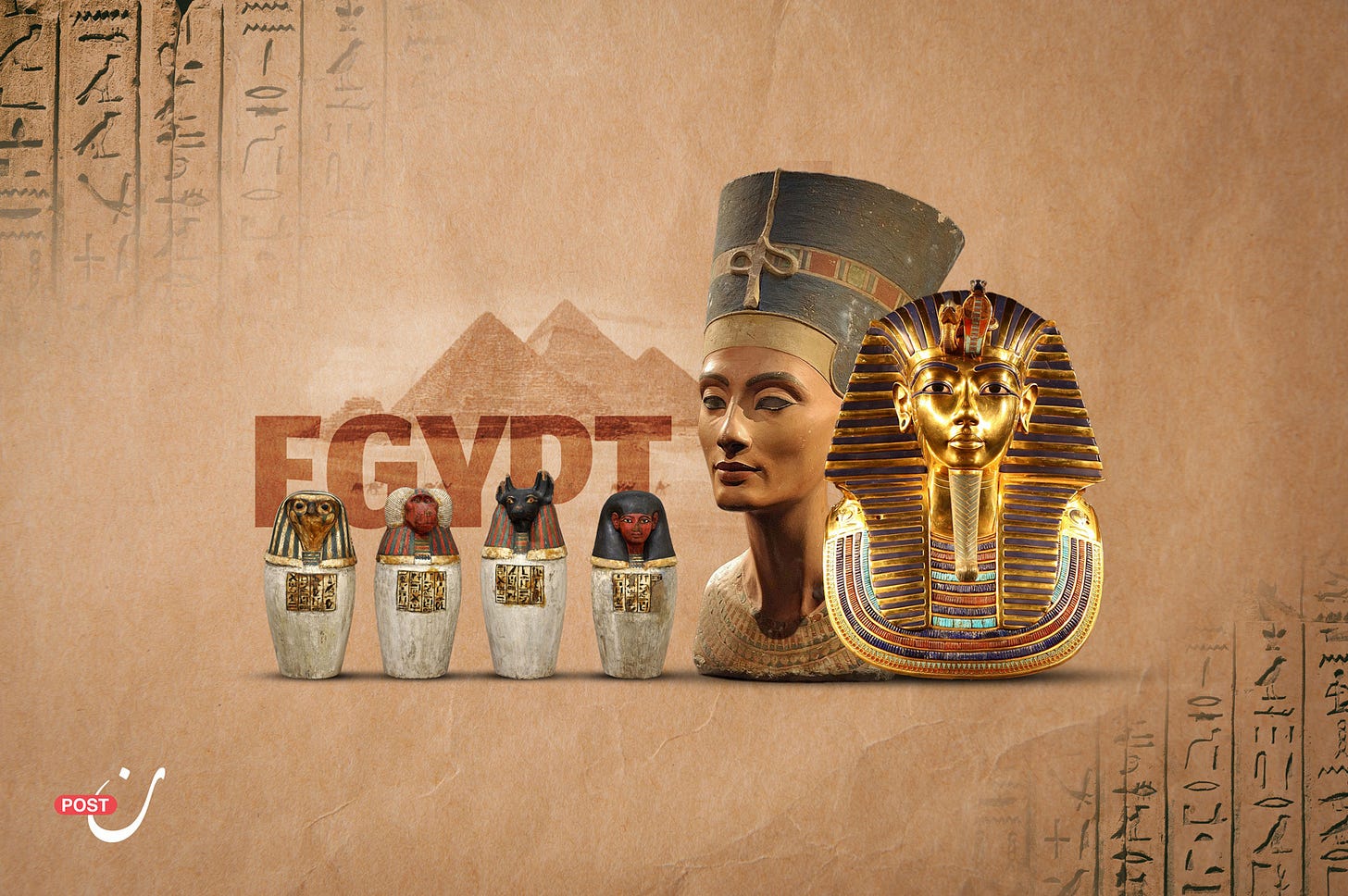

A Monumental Legacy

Every civilization that took root on Egyptian soil has left behind a wealth of archaeological landmarks that bear witness to the grandeur of this nation. The most prominent is, of course, the Pharaonic civilization, which spanned nearly 3,000 years and gifted humanity some of its most enduring cultural achievements.

Among Egypt’s most iconic monuments are the Giza Pyramids—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—the Bent Pyramid and the Red Pyramid of Sneferu, considered by historians to be among the oldest in existence. Nearby, the Sphinx still guards the necropolis as it has for millennia.

Temples such as Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple (1458 BCE), Luxor Temple (1392 BCE), Abu Simbel (1257 BCE), and the Karnak complex showcase the architectural and religious sophistication of ancient Egypt. Sacred cities like Abydos in Sohag, home to the temples of Seti I and Ramses II, and the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, with its royal tombs, offer a glimpse into funerary traditions and beliefs.

Following the Pharaonic era came the Ptolemaic rule (starting 323 BCE), when Greek-Macedonian influence flourished. Alexandria, the “Bride of the Mediterranean,” became a hub of classical antiquity, boasting temples, amphitheaters, necropolises, and cultural institutions.

Then came the Coptic era (4th to 9th century CE), during which Christianity spread across the country. Churches like the Hanging Church, St. Barbara’s Church, St. Sergius and Bacchus, and St. George's Church reflect a rich spiritual and architectural heritage.

The Islamic conquest of Egypt in 641 CE ushered in another era of artistic and architectural brilliance. Structures like Amr ibn al-As Mosque (641 CE), Al-Azhar Mosque (970 CE), Ibn Tulun Mosque, Sultan Hassan Mosque, and the Citadel of Saladin still define the historical heart of Cairo.

The Long History of Looting

Archaeological theft in Egypt dates back to Roman times, when invaders plundered massive quantities of treasures. The situation intensified after the deciphering of hieroglyphs in 1822, sparking a European frenzy for Egyptian artifacts.

The French (1798–1801) and British (1882–1922) colonial occupations were especially prolific in their looting. Entire cities and obelisks were removed and are now displayed in European capitals, enabled by exploitative laws that denied Egypt any claim to its own heritage.

Experts identify three main methods of smuggling:

Foreign excavation missions: Until Law No. 117 of 1983, foreign missions were entitled to a share—up to 10%—of their discoveries. The new law made all such finds property of the state, though it allowed exceptional rewards in rare cases.

Illicit excavation and trafficking: Private smugglers and criminal networks—sometimes aided by military officers, diplomats, or officials—carried out large-scale operations using land, sea, and air routes.

Museum thefts: Artifacts have been stolen from museums and storage facilities, particularly after the 2011 revolution. Entire containers of antiquities have been seized in recent years during attempted exports.

A significant number of artifacts also left the country as official gifts. President Gamal Abdel Nasser infamously gifted entire temples to countries that aided in the construction of the High Dam. Among these were the Temple of Dendur (to the US), Taffeh (Netherlands), Ellesyia (Italy), Debod (Spain), and part of Kalabsha (Germany).

A Million Smuggled Pieces

While there is no exact figure, experts agree that at least one million Egyptian artifacts reside in more than 50 museums abroad. Leading the list are:

UK museums: 275,000 items in 7 major museums, including the British Museum (100,000), Petrie Museum (80,000), and Ashmolean Museum (40,000).

US museums: About 220,000 items across 15 institutions, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

German museums: 104,000 artifacts, mostly in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum (80,000).

Italian museums: Over 60,000 items, with Turin’s museum alone holding 32,500.

French museums: 52,000 artifacts, mainly in the Louvre (50,000).

Other countries include Russia, Canada, Austria, Greece, and the Netherlands.

Even massive obelisks—like Cleopatra’s Needle in London and New York, or Thutmose III’s in Istanbul—were transported with official complicity, beyond the capacity of ordinary smuggling.

These museums generate hundreds of millions of dollars annually from these displays, while Egyptian museums often struggle with low visitation, poor marketing, or mismanagement.

Legal Barriers and Recovery Efforts

Multiple international conventions govern cultural property theft:

1970 UNESCO Convention: Urges states to protect cultural heritage and prevent illegal import/export of antiquities.

1972 World Heritage Convention: Requires signatories to counter illicit trafficking.

1995 UNIDROIT Convention: Demands restitution of stolen or illegally exported cultural objects.

Bilateral agreements have also been effective, such as the Egypt-Switzerland accord enacted in 2011.

However, most smuggled artifacts cannot be reclaimed. Those given to foreign missions pre-1983, or gifted by heads of state, are considered legally transferred. Only items officially recorded in the Ministry of Antiquities’ registries and stolen from museums or storerooms can be reclaimed.

Shaaban Abdel-Gawad, head of Egypt’s Recovered Antiquities Department, says that the Ministry actively monitors auctions and online sales. If an item is identified, they request proof of ownership. Absent such proof, the item is considered stolen, and legal recovery procedures are initiated through the Ministry of Justice and Interpol if needed.

Egypt has successfully retrieved some artifacts from the US, UK, France, Italy, occupied Jerusalem, and Belgium—and continues its efforts to reclaim as many treasures as possible. With the right combination of will and governance, these artifacts could become a vital source of national pride and economic prosperity.