It has become increasingly clear that the war in Sudan has long surpassed the bounds of an internal crisis confined within national borders. The trajectory of the conflict, its geographic expansion, and the multiplicity of actors involved have rendered its repercussions a major force in shaping the broader regional environment potentially altering the existing balance of power in ways fundamentally different from the current status quo.

In this context, the fall of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) marked a critical turning point in the war that erupted in mid-April 2023. The seizure of this particular city is not merely a significant battlefield gain for one side of the conflict; it signals a dangerous new phase in which Sudan’s national integrity and central authority appear to be unraveling, threatening the very survival of the state as a cohesive political entity.

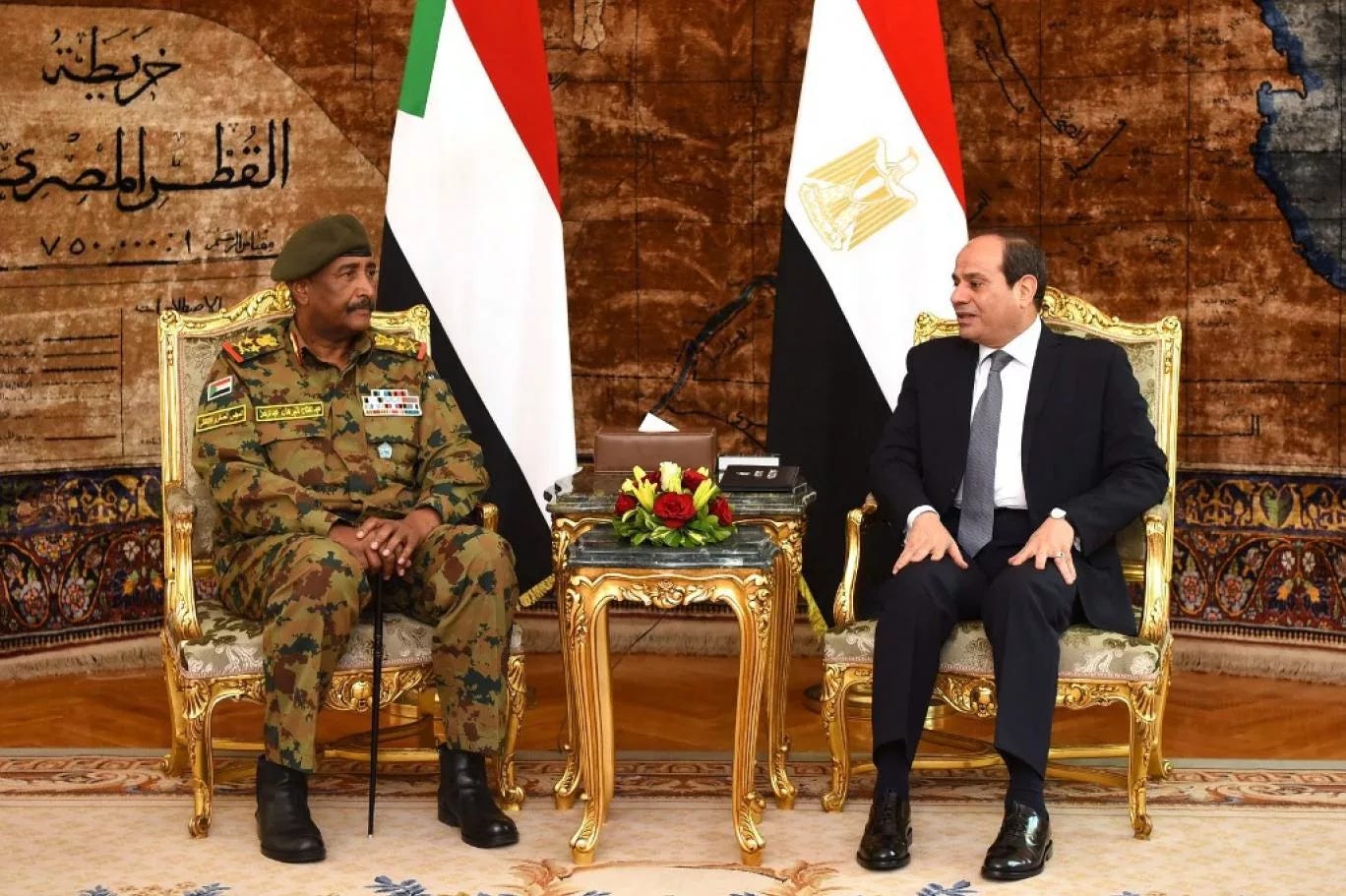

On October 26, the UAE-backed RSF announced full control over El Fasher following intense battles that culminated in the capture of the Sixth Division’s headquarters the Sudanese army’s final stronghold in the city. Army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan later confirmed the withdrawal, citing the need to avoid further bloodshed.

This pivotal moment laid bare the shifting balance of power on the ground and suggested that scenarios involving national fragmentation have become increasingly likely. The development quickly reverberated across the region, particularly in Egypt, due to its geographical proximity and long historical entanglement with Darfur and Sudan at large.

For months, Cairo had sought to maintain a calculated distance from the conflict, adhering to a restrained, quasi-neutral policy. But the current trajectory has rendered such a stance increasingly untenable. Egypt’s national security now faces alarming and unpredictable risks not only militarily and politically, but also socially, demographically, and economically.

Why Does El Fasher Matter to Egypt?

El Fasher holds particular geopolitical significance for Egypt. As the capital of North Darfur, it serves not only as a regional hub but also as a logistical anchor point with direct implications for Egyptian national security. Located over 800 kilometers west of Khartoum and approximately 195 kilometers from Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, El Fasher lies at the heart of Sudan’s western interior and offers control over strategic routes leading toward the broader regional borderlands.

For a long time, El Fasher symbolized one of the final bastions of Sudan’s central government, represented by the army and civil authorities. Despite months of ongoing clashes, the city’s resistance to a full RSF takeover had made it a focal point in the balance of power. Its fall now signifies not only a strategic military loss but also a possible collapse of the symbolic and structural remnants of Sudan’s central authority.

Beyond its military relevance, El Fasher is a crucial node in smuggling networks that span Darfur and beyond particularly in arms and gold trafficking. Control over the city grants access not just to territory, but to wealth, resources, and regional influence that extends far beyond Sudan’s borders.

Thus, its fall is more than just a battlefield development; it represents a geopolitical inflection point that could redefine the contours of the future Sudanese state. El Fasher stands as a historical crossroads: a point at which the country’s trajectory toward either unity or fragmentation may ultimately be decided.

This dynamic has left Egypt with little choice but to become directly involved, not by preference but by necessity. The potential fallout is too consequential: from border security to strategic interests and the broader balance of power in the region.

Cairo’s Four Strategic Lenses

Since the fall of Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and the descent into open war in April 2023, Egypt’s approach to Sudan has been shaped by four core areas of strategic concern:

1. Security Concerns:

The more than 1,200-kilometer shared border mostly ungoverned desert terrain creates fertile ground for cross-border crime and informal economies, including arms and drug trafficking and the movement of armed groups. These dynamics elevate the risk of militant infiltration into Egypt, a threat potentially as severe as those emanating from Sinai or Libya.

Tensions between Cairo and the RSF have also been rising, with both sides trading accusations of interference and bias. If the RSF consolidates its hold on Khartoum, retaliatory moves against Egypt could become more likely.

2. Economic and Social Pressure:

Egypt is already absorbing significant fallout from the Sudanese crisis, particularly through the arrival of nearly 4 million displaced Sudanese nationals, according to unofficial estimates. This influx has placed considerable strain on Egypt’s fragile economy and overburdened infrastructure.

Should Sudan continue toward fragmentation and persistent instability, further waves of displacement are almost inevitable compounding Egypt’s social, economic, and security burdens.

3. Political Alignment:

Sudan has historically been Cairo’s most critical strategic partner to the south. The idea of a united Sudan has always been integral to Egypt’s national security doctrine. Fragmentation would force Cairo to navigate a complicated political terrain of competing factions limiting its ability to shape a coherent foreign policy and increasing the risk of direct confrontation with one side or the other.

More concerning, Sudan’s descent into division is playing out within a wider geopolitical contest: Washington and Riyadh are seen as closer to the Sudanese army, while Moscow and Abu Dhabi support the RSF. This dynamic risks turning Sudan into an international proxy battleground right on Egypt’s doorstep at a time when Cairo can ill afford new external tensions.

4. Water Security and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD):

Sudan has traditionally aligned -at least nominally- with Egypt in opposing Ethiopia’s unilateral actions on the Nile. However, a fragmented or weakened Sudan would undercut Cairo’s negotiating leverage and potentially open the door for greater Ethiopian influence via its warming ties with RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemeti). Such a shift could compromise Egypt’s water security perhaps its most vital strategic concern.

These four factors do not operate in isolation. Together, they form a complex, interwoven web of national interests that ties Egypt’s future closely to that of Sudan. Cairo can no longer afford the luxury of detachment. The outcome of this war will have a direct and profound impact on Egypt’s borders, security, and regional standing.

What Are the Potential Consequences?

These four lenses security, economic, political, and hydrological have previously acted as restraints on Egypt’s engagement, pushing it toward a policy of limited involvement. Even where there may have been indirect support for the Sudanese army, Egypt largely tried to preserve a balance. But the fall of El Fasher has disrupted that equilibrium.

The underlying premise for neutrality that neither side could decisively shift the status quo no longer holds.

Now, with the RSF moving dangerously close to Egypt’s strategic periphery, inaction is no longer viable. Cairo views this as a critical juncture, with three main threats looming:

1. Redrawing the Geopolitical Map South of Egypt:

If the conflict continues to advance into Kordofan after El Fasher, Sudan’s division could become a de facto reality resembling an unofficial confederation in which the east and west function as separate political, military, and economic entities.

This could create a bifurcated southern frontier for Egypt: one aligned with the official army, the other a paramilitary-controlled zone tied to Hemeti. Such a scenario poses a direct logistical and strategic threat to Egypt’s national security.

2. Expanded Smuggling and War Economy Networks:

El Fasher’s strategic location along arms and gold smuggling routes means RSF control could fuel expanded illicit flows into Egypt’s borders. This would not only exacerbate existing black-market dynamics but might also invite rival regional actors to exploit the power vacuum, undermining Egypt’s influence.

Increased displacement and cross-border flows could overwhelm Egypt’s already strained social and economic systems.

3. Weakened Nile Negotiation Bloc:

Egypt has long counted on a united Sudan to bolster its negotiating position on the Nile. A fragmented Sudan would rob Cairo of this critical ally. Ethiopia could leverage its relationship with Hemeti to further entrench its GERD project, structurally shifting the negotiating landscape to Egypt’s disadvantage.

In sum, the fall of El Fasher marks a before-and-after moment for Sudan and for Egypt. It has reshaped the strategic pressure on Cairo, forcing a reassessment of the limits of neutrality and the boundaries of intervention.

Egypt’s Strategic Options

Since the war broke out, Egypt’s room for maneuver has steadily narrowed. El Fasher’s fall may have brought Cairo to a critical threshold: neutrality is no longer feasible, and disengagement is no longer an option. If Sudan collapses into full-blown chaos, the consequences could be far worse than the current Libyan scenario.

Sudan is three times larger than Libya and saturated with arms supplied by various external backers. The potential for conflict spillover into Egypt is thus far more severe. This is why Cairo continues to cling, even if tenuously, to the idea of a “recoverable central state” -however distant- rather than accepting a fragmented reality dominated by militias.

Going forward, Egypt appears to have two primary pathways:

Option 1: Directly Support the Sudanese Army

This is a high-risk strategy. Given the RSF’s consolidation of Darfur, any overt Egyptian support for the army could spark a dangerous escalation, especially considering the previously hostile rhetoric between Hemeti and Egyptian officials. The cost of this option is high and fraught with the risk of open confrontation.

Option 2: Strengthen Diplomatic Channels and Restore Balance

This is the more likely short- to mid-term strategy. Egypt could seek to re-engage both sides through parallel diplomatic channels to de-escalate tensions and prevent a permanent territorial division.

Cairo has precedent in this approach, and may seek to involve regional (especially Gulf) and international partners to increase pressure and avoid full internationalization of the conflict.

Should the war be fully internationalized, Egypt risks losing its leverage entirely, with Sudan becoming a laboratory for external power strategies developed far from the region—posing grave threats to both Egyptian and Arab security.

In the interim, Egypt is expected to dramatically tighten its border controls not only with Sudan, but also with Libya, and potentially extending deeper into Chad if necessary. Border management and risk containment have become top priorities until a viable political process can be reestablished one that restores the prospect of a functional Sudanese state.

Sudan’s war has entered a new and perilous phase. The dramatic fall of El Fasher is more than just a battle lost it is a collapse in the image of a unified Sudan and a blaring warning that the country may be nearing the point of no return.

This shift doesn’t just affect Sudan internally it’s reshaping regional dynamics and re-opening existential questions about the future of the nation-state model in the Horn of Africa. For Egypt, this is a strategic test of the highest order. Time is no longer on its side, and passivity is no longer sustainable.

Without robust political intervention and coordinated regional action, the disintegration of Sudan may become a reality one that threatens the security and stability of the entire region.

Maintaining even the minimal structures of a functioning Sudanese state is no longer just a Sudanese imperative it is a regional necessity.