When steamships set sail from Marseille in the early 19th century, bound for the northern shores of Africa, they carried more than just passengers. They transported a romanticized vision of the Orient—an image crafted by printing presses, ink, and imagination long before it met the eye.

On the walls of ports, in train stations, and inside cafés across French cities, advertisements began to promote travel by ship, then by car, train, and eventually by airplane to Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. These destinations weren’t presented as sovereign states, but rather as mysterious, enchanting realms, cloaked in an alluring Orientalist fantasy.

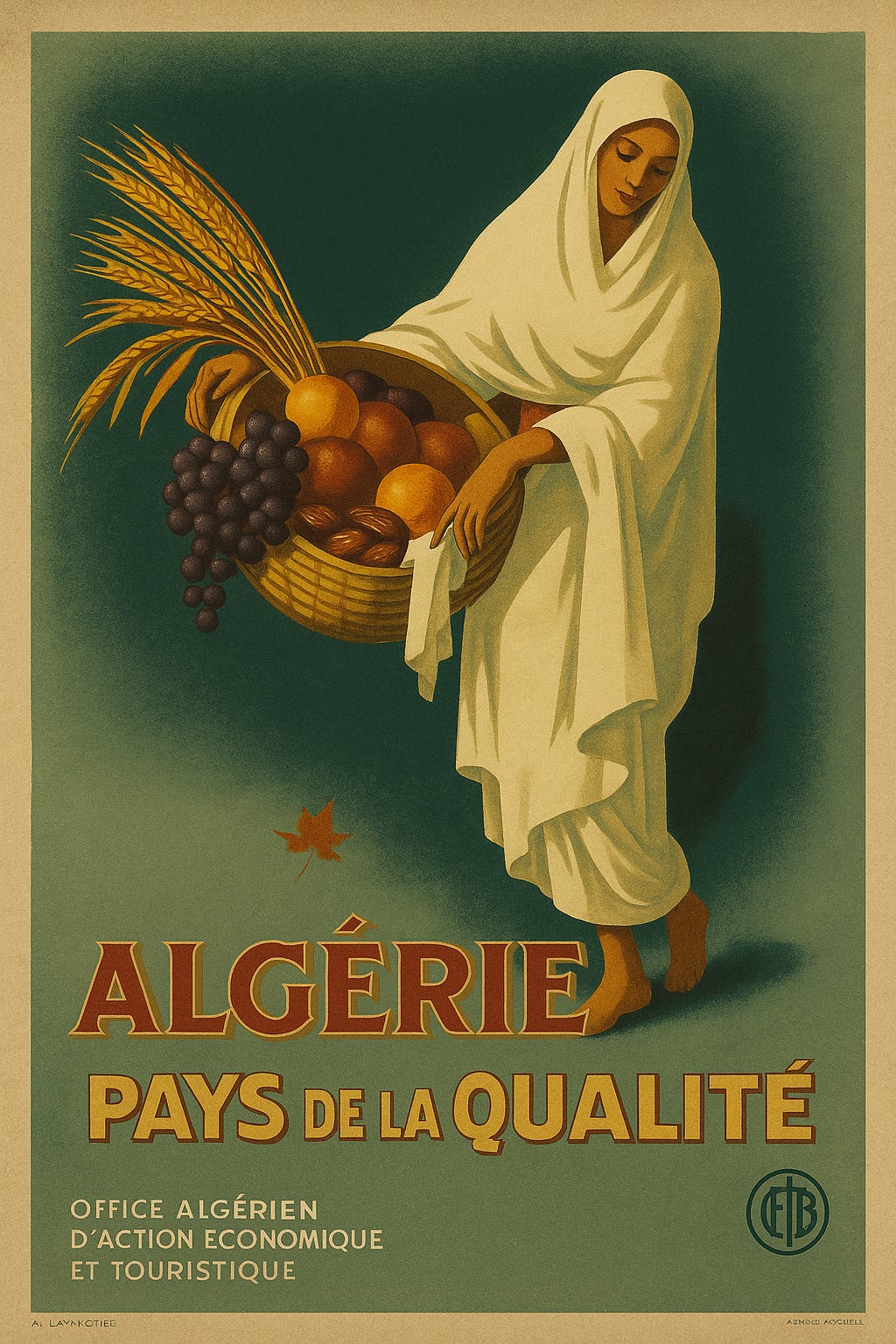

These posters were more than mere marketing tools for steamship lines or travel to the "lands of the sun." They reflected the West’s imagined gaze upon the East: veiled women in tranquil riads, bustling souks splashed with color, and camels disappearing into the desert haze.

The Arab "other" was rendered with romantic fascination and subtle bias, using carefully selected visual elements—ornate palaces, veiled women, mosaic-covered doors, vibrant spices—to conjure an exotic dreamscape.

This vision was part of a broader mechanism now referred to as "colonial tourism," in which Maghrebi lands were sold as serene, picturesque, and pacified territories, ideal for discovering "wonders" or escaping the drudgery of industrial Europe.

By the early 20th century, Orientalist posters emerged as a distinct art form. They were showcased in commemorative exhibitions, such as the Spanish Pavilion at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, which featured an Andalusian palace that inspired artists like Georges Clairin and Henri Dinet.

Later colonial exhibitions followed, including the 1906 Marseille Expo and the 1930 Algiers Expo, commemorating a century of French occupation.

The Image as a Colonial Tool

In Morocco, businessman and art collector Abderrahman Slaoui took a keen interest in Orientalist posters, embarking on a tireless quest to locate them across Paris, Brussels, Geneva, London, Canada, and the United States, often poring through auction house catalogs.

In April 1994, Slaoui organized a small exhibition of his collection, timed to coincide with the signing of the Marrakesh Agreement, which paved the way for the creation of the World Trade Organization. The concept was inspired by a factory that specialized in movable commercial signage, whose designs had a similar mobility.

This early exhibit was closed to the public and attended only by delegates and diplomats. Many attendees urged Slaoui to present the collection in a larger, more permanent venue.

Two years later, in June 1996, the collection was exhibited for two months at the Arab World Institute in Paris. Slaoui later established a permanent exhibition at the Abderrahman Slaoui Museum in Casablanca, housing his acquisitions from around the globe. These hundreds of visually striking and historically significant posters documented a century of Orientalist advertising.

His efforts culminated in the 2010 publication of a richly illustrated book, The Orientalist Poster: A Century of Advertising, by Malika Editions. Though the book was never translated into Arabic, it includes an essay by Abdelaziz Ghouzi, director of the Ibn Siraj Library in Paris, who offers a critical reading of the posters—not just as travel ads, but as cultural artifacts charting Europe’s complex and layered relationship with North Africa.

Also featured is a foreword by former French Foreign Trade and Foreign Affairs Minister Michel Jobert, adding an official tone to the book’s cultural weight.

A Ticket to the Other East: How They Saw Us

Tourism in North Africa began in earnest in the early 1890s, when shipping companies allowed the PLM Railway (Paris–Lyon–Mediterranean) to expand into Algeria and later Tunisia. This marked the birth of an organized colonial tourism industry.

As Ghouzi notes, advertising posters became a primary means of commercial communication in the 20th century. France played a significant role in promoting them to support its colonial agenda.

The earliest of these travel posters date back to 1891 and 1892, when artist Hugo d’Alési created promotional posters for PLM, showcasing Orientalized scenes from Algeria and Tunisia designed to captivate European tourists.

Travel brochures also emphasized the "radical differences" between France and the Maghreb, enhancing the exotic appeal and presenting these territories as "the other France," suggesting both geographic and cultural extensions of the French Empire.

Before World War I, tourism to the Maghreb was largely seasonal, restricted to the winter months. Promotional texts of the era painted a vivid picture:

"There are fewer houses than in France, vast open lands, no fences separating the fields, and red or brown clay huts instead of stone buildings. On the road, locals travel with horses, camels, or mules, unbothered by long distances. In the Maghreb, the tourist steps into another world—yet feels at home, thanks to France’s influence."

Posters frequently depicted North Africans with dark skin, Amazigh dancers, or labeled settlements as “Berber,” a term that originally bore pejorative connotations of primitiveness and savagery, derived from the Latin barbarus, which Romans used to describe non-Greek or non-Latin-speaking peoples.

One common motif was the Moroccan Sultan on horseback en route to the mosque, flanked by his entourage. Algerian minarets—especially those of Tlemcen—appeared regularly, alongside fully veiled Algerian women. In contrast, Tunisian posters often portrayed more "liberated" female imagery, by Western standards.

European women in bikinis appeared on the beaches of Agadir and Tunis, or in golf carts at exclusive resorts, juxtaposed against traditional depictions of locals—reinforcing the visual divide between the "civilized" European visitor and the "primitive" Orient.

Egyptian posters, meanwhile, offered a different appeal: winter warmth and ancient pharaonic splendor, targeting tourists in search of sun and history.

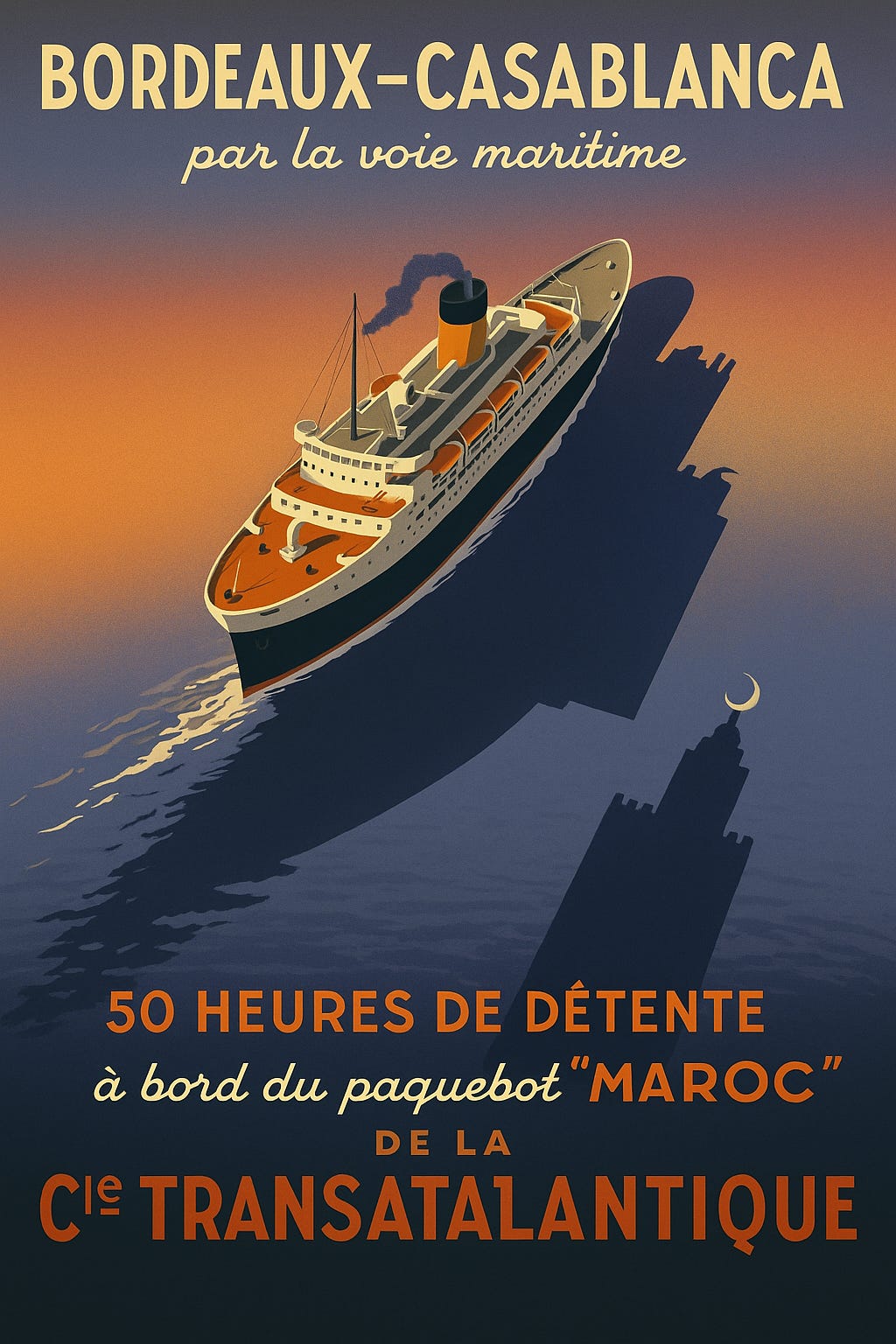

During World War I, North African countries were called upon to support the Allied powers. Posters encouraged enlistment, subscriptions, and loans to "liberate France" and bring soldiers home. Between the wars, as transportation evolved, the golden age of the travel poster emerged.

By then, the sea journey from Marseille to Algeria took 22–26 hours, to Tunisia 30 hours, and to Morocco around 3 days. Air travel reduced that to 6–10 hours.

The Maghreb Through the European Poster

Major transportation firms promoted the Maghreb as an “exotic yet accessible” destination, commissioning artists like Broders, Romberg, and De La Nézière for poster campaigns. Early designs were text-heavy, packed with visual lures.

In 1920, tourism offices opened in Algeria, Tunisia, and Casablanca. These favored hiring local artists to better convey a sense of place, leading to a shift toward more minimalist poster designs without excessive annotations.

Printed locally—most notably by the Baconnier press—these posters used bold lighting and striking color gradients. Artists included Josset in Tunisia; Koffi, Carré, and Thell in Algeria; and Majorelle, Drésch, and Brondy in Morocco. Some pursued an explicitly colonial vision, while others simply expressed an artistic interest in local culture.

Jacques Majorelle settled in Marrakech and created the now-famous garden that bears his name. Gabriel Rousseau authored books on Moroccan fashion, and his posters reflected that. Mariano Bertuchi Nieto, active during the Spanish protectorate, managed several museums, including the one in Tetouan.

Shipping and railway companies integrated posters into broader marketing strategies. They adorned travel agencies, train stations, ports, and tourist offices, capturing the imagination of prospective travelers.

Though produced as ephemeral ads, many posters survived and now serve as rich visual records and fertile ground for cultural analysis.

Patrick Boulanger of the Marseille Heritage Office notes in the book that these posters offered Europeans a fantastical glimpse into foreign lands, blurring the line between reality and myth.

Famous steamship companies like Paquet, Cie Générale Transatlantique, and SS Champollion hired renowned artists such as Édouard Collin, Hugo d’Alési, Roger Broders, Jacques Majorelle, Louis Lessieux, Mathieu Brondy, and Maurice Romberg.

Over time, visuals overtook text, making posters resemble "telegrams to the mind."

The Paquet Steamship Partnership

Maritime travel to Morocco was particularly fraught due to the country’s unprepared ports and hazardous coastlines. Strong waves often forced ships to anchor offshore for days, with cargo transferred by small boats.

Trade between Marseille and Morocco involved French exports of candles, sugar, and soap, in exchange for Moroccan wool, leather, and olive oil. By 1900, Paquet Line, owned by Nicolas Paquet, dominated maritime routes to Morocco with eight ships—some of which sank in Moroccan waters due to harsh conditions, though no lives were lost.

Nicolas Paquet pioneered a French-Moroccan shipping partnership, inviting local Muslim and Jewish traders as shareholders. The initial partners included Abdelkader Attar, Mokhtar Ben Azzouz, Yves Bergil, David Corcos, and Massoud Lasri.

Between 1900 and 1914, this partnership spurred exponential growth: the fleet grew to over twenty ships, and Paquet was responsible for producing more than a third of all Moroccan-themed posters of the time.

This special relationship showed in the posters, which portrayed Morocco with unmatched artistic enthusiasm. A square in Casablanca still bears Nicolas Paquet’s name, though his company now offers luxury cruises under "Croisières Paquet."

These posters now evoke nostalgia for the grand steamship era, for the romance of Mediterranean voyages, and the luxury of maritime travel. Though planes eventually replaced ships, the surviving posters preserve a vibrant memory of that bygone time.

The Age of Aviation

The first regular air service between France and Morocco began in 1919 via the French airline Latécoère, which later merged into Aérospatiale. Favorable Moroccan weather made it an ideal base for launching these pioneering intercontinental flights.

Even earlier, in 1916, a route from Toulouse to Rabat via Barcelona, Alicante, and Málaga allowed air travel in 16–18 hours—considered one of the world’s earliest intercontinental journeys.

In Algeria, Latécoère launched a Marseille–Algiers route in August 1928 with three weekly flights, which became daily by the next year. In 1929, Air Union—predecessor to Air France—introduced three weekly flights from Marseille to Tunis. Soon, trans-Mediterranean air travel expanded rapidly.

As travel posters flourished, a new genre of commercial posters emerged promoting Oriental-themed products—soap, coffee, cigarettes, and carpets—featuring turbaned Arab men and seductive Eastern women.

Anyone browsing these hundreds of Orientalist ads will detect a double gaze: one that reduced the East to mystical tropes, swaying between aesthetic admiration and cultural condescension. These images were far from innocent; they carried political and colonial undertones shaped by Western imagination, not the lived realities of Eastern societies.

Today, revisiting these posters with a critical eye is less about condemning them as art, and more about deconstructing the visual discourse they carried—liberating the visual consciousness from inherited stereotypes in hopes of creating a more just, balanced image of the East and its people.