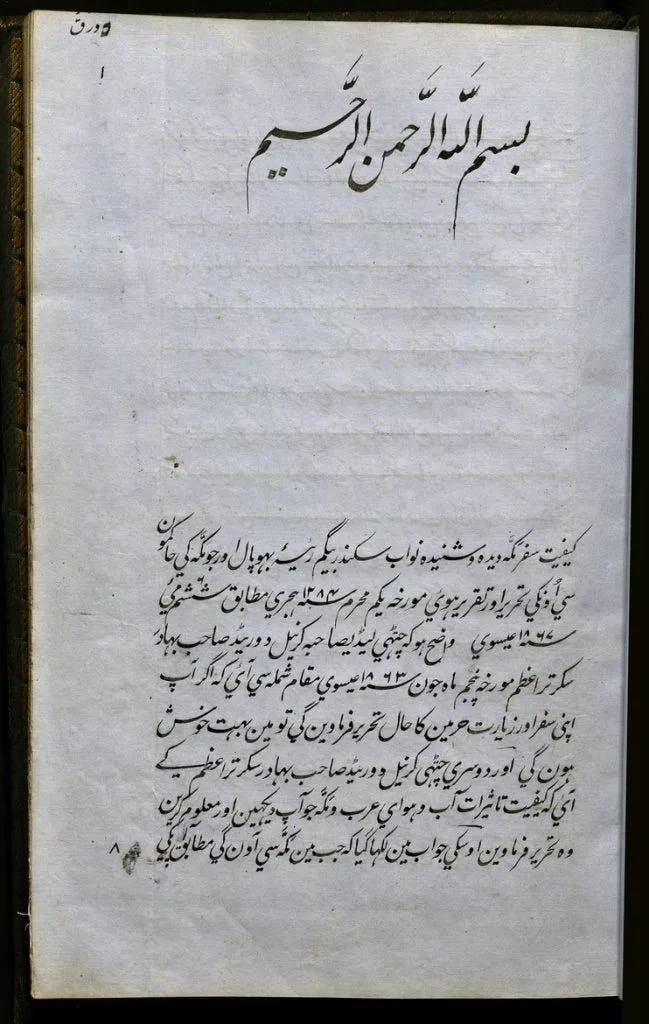

Since the 19th century, South Asian Muslims experienced a transformation in their self-awareness as a result of contact with European ideas under colonialism. With the decline of the Mughal Empire in the early 18th century, hundreds of semi-independent principalities emerged, gradually aligning themselves with the British—especially after Britain consolidated control over India by the mid-19th century.

Among the most notable of these was the central Indian principality of Bhopal, which was ruled by four women, the most prominent of whom was Sikandar Begum. In 1864, she performed the Hajj and resided in the Hijaz for six months, documenting her pilgrimage in a book titled A Princess of Bhopal’s Account of the Hajj, the first published Hajj narrative by an Indian woman.

In her account, Sikandar Begum offered a critical and vivid depiction of her pilgrimage, expressing personal impressions of Mecca and its inhabitants. She boldly addressed the region’s religious, social, and political conditions, capturing a vibrant portrait of life in the Hijaz before the advent of modern transportation transformed the pilgrimage in the 20th century.

From India to Jeddah

Born in August 1818, Sikandar Begum received an exceptional education, equipping her for excellence in governance and politics. During the 1857 Indian Rebellion, she sided with the British, securing their political support in the aftermath.

Her reign was marked by ambitious reforms—fiscal, military, and social. She paid off Bhopal’s debts, overhauled its revenue and judicial systems, developed the police, transportation, education, and civil administration, and established hospitals and schools with a special focus on women’s education.

She also changed Bhopal’s official language from Persian to Urdu. Her rule is widely considered Bhopal’s golden age.

Despite her deep engagement in state affairs, Sikandar Begum saw herself as a devout Muslim who maintained the five daily prayers and harbored a sincere longing to perform the Hajj. She regarded the pilgrimage as the pinnacle of her belonging to the global Muslim ummah.

Late in life, she resolved to embark on the pilgrimage. Before departing Bhopal, she prayed two rak'ahs at the Mamola Sahib Mosque near her palace, recited Qur'anic verses and supplications, then retreated to the Farhat Afza garden, where she spent two days finalizing state matters and preparing for her journey.

Sikandar Begum began her pilgrimage on 5 November 1863 (22 Jumada al-Awwal 1280 AH), accompanied by a caravan of about 1,500 pilgrims from Bhopal, most of them women—including her mother. The group traveled to Mumbai, then sailed on three chartered ships carrying enough provisions for a year, along with jewelry, clothes, and charitable donations intended for the poor of Mecca and Medina.

The four-month voyage across the Indian Ocean to Jeddah was uneventful, and the caravan arrived at the port on 23 January 1864 (13 Sha'ban).

Upon entering the city the next day, she was met with lit lanterns and celebratory gunfire. When she inquired about the occasion, some locals said it marked the Ottoman Sultan’s birthday, while others claimed it was in celebration of Laylat al-Bara’ah (mid-Sha’ban).

She stayed in a simple lodging of square, palm-frond huts—military-camp-like dwellings with open wall vents and no ceilings to keep out the sun. This type of shelter accommodated all pilgrims, with more lavish sections reserved for nobility.

In Jeddah, Sikandar Begum expressed admiration for the local sweets—fruit-filled cakes and jams—but also noted the severe scarcity of clean drinking water, which had to be fetched from reservoirs a mile and a half away.

Eventually, she departed Jeddah for Wadi Dhul-Tuwa, where she was greeted by 80–90 foot soldiers and 60–70 cavalrymen. She declined to proceed with them, insisting on first bathing in the well of Dhul-Tuwa in accordance with prophetic tradition.

In the Heart of Mecca

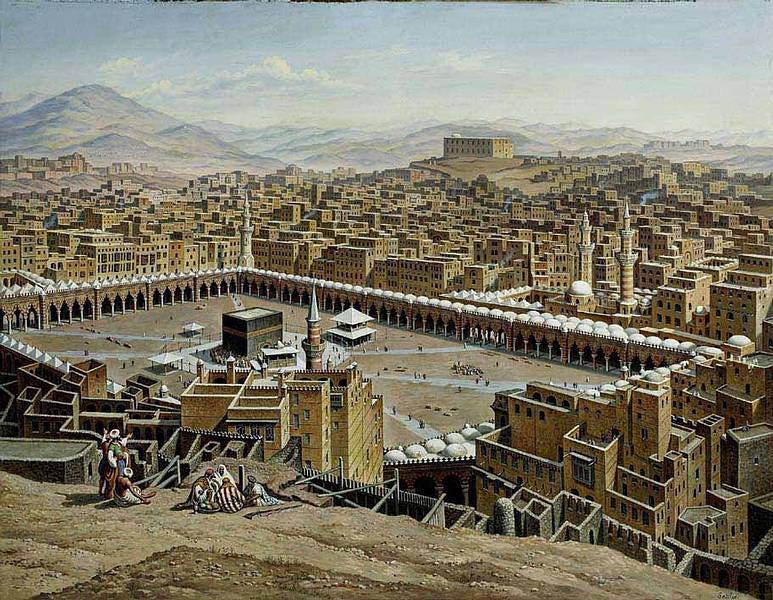

Sikandar Begum arrived in Mecca on the night of 27 January 1864 (17 Sha'ban 1280 AH), as the call to prayer echoed through the city. Entering through Bab al-Salam, she paused reverently at the Station of Abraham, recited traditional supplications, and performed the arrival circumambulation followed by the sa’i between Safa and Marwah. She then headed to a rented house for her stay in Mecca.

Interestingly, unlike many pilgrims who describe their emotional reactions upon seeing the Kaaba, Sikandar Begum did not recount a deeply spiritual experience. Her focus remained on critiquing the cultural and social aspects of the pilgrimage rather than introspective religious reflections.

She chronicled a wide array of observations—weather, horses, sweets, vegetables, windmills, and luxurious gender-segregated bathhouses. She praised the Arabian horses as noble and expensive, was captivated by Mecca’s moonlight, and admired the city’s ornate carpets and sofas.

“Mecca is not cold, but the heat begins about an hour before sunrise, just like during the day. The moonlight in Mecca is splendid, as the air is dry, the sky cloudless, and the horizon unpolluted.” (p. 168)

She noted that Mecca’s call to prayer was heard five times daily, as in India, but an additional call was made at night. At sunset, locals supplicated and praised God, and at sunrise, they recited verses from the Qur’an and traditions of the Prophet and his four successors.

She observed widespread camel, cow, goat, and sheep herding, with no buffalo. Donkeys and mules were fast but poorly fed, and stray dogs, cats, and insects were abundant.

The Meccans, she noted, consumed large quantities of meat, tea, and ghee. Bedouins, she wrote, preferred raw foods—honey, dates, clarified butter, and even locusts. She was surprised by the absence of salt in local cuisine despite the abundance of pickles.

Meccan houses, she said, were multi-storied and lacked courtyards. She detailed their food, dress, and lifestyle, noting that dancing and singing were officially banned, though women sang and clapped during weddings.

On water access, she reported that wells were rare and expensive. Poorer residents were barred from the springs controlled by soldiers. A water bag cost half a qirsh, though nobles received their supply for free. She was granted access to the water she needed.

Hijazi clothing varied widely—urban dwellers wore traditional garb, while Bedouins dressed in skins and palm-frond headdresses. There was no standard attire in Mecca, as each person wore what was customary in their homeland.

Sikandar Begum described stark disparities in living conditions, documented the bustling slave market, and detailed the daily lives of enslaved Africans and Georgians who cleaned, cooked, fetched water, and lit lamps during the Hajj. She also discussed social norms around concubinage.

“The slave market in Mecca is lively, and men and women of various nationalities are displayed... Many are sold by locals to pilgrims.” (p. 120)

The Princess’s Critiques

Sikandar Begum’s critical perspective was shaped by her status as a ruler of a principality of 9,000 square miles with nearly one million people. She did not hide her disappointment with Mecca’s conditions and had open disputes with the Sharif of Mecca and the Pasha of Jeddah, rooted in deep cultural and linguistic misunderstandings.

She admitted feeling alienated by the region’s customs and communication barriers, noting that despite their shared faith, she could not establish genuine rapport with Arabs or Turks.

“I began to question the purpose of coming to Mecca for worship.” (p. 126)

Diverse Social Concerns

She criticized local behavior, calling Meccans greedy, harsh, lazy, and corrupt. She decried rampant bribery and dishonest business dealings, comparing them to violent Indian tribes.

She was appalled by the normalization of begging:

“Meccans are wealthy but stingy and gluttonous. Everyone begs—young or old, male or female, noble or poor—and they are never satisfied with what they receive.” (p. 112)

She harshly judged Meccan women, describing them as loud and heavyset, and was especially shocked by prevalent polygamy, noting some women had ten marriages, and most cases involved at least two.

One of the most disturbing revelations for her was the underground sale and consumption of alcohol in Mecca and Jeddah—particularly among Turks and Indians—something she found outrageous in the holy cities.

She also noted varying levels of religious knowledge, with city dwellers possessing basic education, while mountain tribes remained nearly ignorant of Islamic teachings.

Rampant Corruption

She lamented widespread corruption among Ottoman officials and the necessity of bribing customs agents, despite receiving poor treatment. Her belongings were looted by Bedouins upon arrival, and she was furious over exorbitant taxes and theft—including the kidnapping of her mother.

“The Bedouins unloaded our belongings from the camels, scattering and stealing much of it. We couldn’t tell what was lost or stolen.” (p. 78)

She criticized the lack of essential infrastructure—no railways, no telegraph service between Mecca and Medina, or even Jeddah. Her outspoken critique of Ottoman mismanagement stands out:

“If the Sultan gave me the three million rupees he spends yearly on Mecca and Medina’s upkeep, I’d assign the job to my daughter and son-in-law, and you’d see how I’d run things properly.” (p. 164)

Medina: A Journey Abandoned

Although eager to visit Medina, Sikandar Begum canceled her plans due to security threats from Bedouin attacks on the route. Lacking enough soldiers or funds to hire guards, she feared extortion or worse.

Eventually, she returned to Jeddah, then sailed to Aden for coal, before arriving in Mumbai on 21 July 1864. While she returned disillusioned, her granddaughter’s Hajj in the early 20th century was a far more uplifting and spiritually resonant experience.