Thousands of amputees in the Gaza Strip endure compounded pain and bodies weighed down by injury. For months, their dreams have been suspended at the gates of the Rafah border crossing, waiting to leave for treatment and the fitting of prosthetic limbs that could restore a semblance of normal life.

On April 3, 2024, in Beit Lahia, 58-year-old Salah Rajab lost his hand and leg to an Israeli airstrike while out with his cousin to earn a living. He was injured; his cousin was killed.

Salah had supported five families through his agricultural nursery. Now he is jobless and without a breadwinner, as his own son is paralyzed from another Israeli attack. He longs for the chance to receive treatment abroad.

Painkillers no longer ease his suffering, and the only surgery that could help him cannot be performed in Gaza due to severe shortages of medicine and medical equipment.

Speaking to Noon Post with deep anguish, he says:

“My hand and leg are gone. There’s nothing left for me in this world. After my injury, I felt like a dead man without a grave. My life ended here.”

Since losing his limbs, Salah has been unable to adapt to his new reality. He cannot return to farming and is powerless to provide for his family.

“We lived as if in paradise, and now it’s hell—hunger, killing, our bodies torn apart. Living in tents is another misery we cannot bear. They shield us from neither winter’s cold nor summer’s heat,” he says.

Salah suffers from a tumor in his amputated arm. Medicines, once a cure, have become harmful. He waits for the crossings to reopen so he can complete his treatment and be fitted with prosthetic limbs, dreaming of returning to his old life.

He and his family face severe psychological strain, unable to adapt to a life they never chose—made worse by his son’s disability and his inability to accompany him to the hospital. Their hopes rest solely on the border gates.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has described Gaza’s situation as “the largest number of child amputees in modern history.” Throughout the 17-month war, supplies and services for amputees—children and adults alike—have been woefully insufficient for the overwhelming need.

A ceasefire in mid-January allowed aid agencies to bring in more prosthetic limbs, wheelchairs, crutches, and other devices, but these have met only about 20% of total requirements.

A Shared Reality of Pain

Like Salah, 22-year-old Rima Abu Aita is among the thousands of amputees. An Israeli airstrike on her home cost her both legs and the fingers of her hands. She now lives with devastating physical and psychological trauma.

Through tears, she recalls:

“I was like a butterfly with dreams. But after my injury, my life turned upside down. Now I have no legs, no fingers—no use in this life.”

Rima requires constant care and treatment, but medicine shortages have made this impossible. Gaza’s hospitals are ill-equipped to fit thousands of amputees with prosthetics. Her only hope is to travel abroad.

“The hardest thing a person can endure is helplessness,” she says. “Even in the tent, I cannot move or meet the simplest needs without help from my family.”

Her sense of helplessness has worsened her physical and mental health. She fears losing her mother—the only one who can care for and understand her.

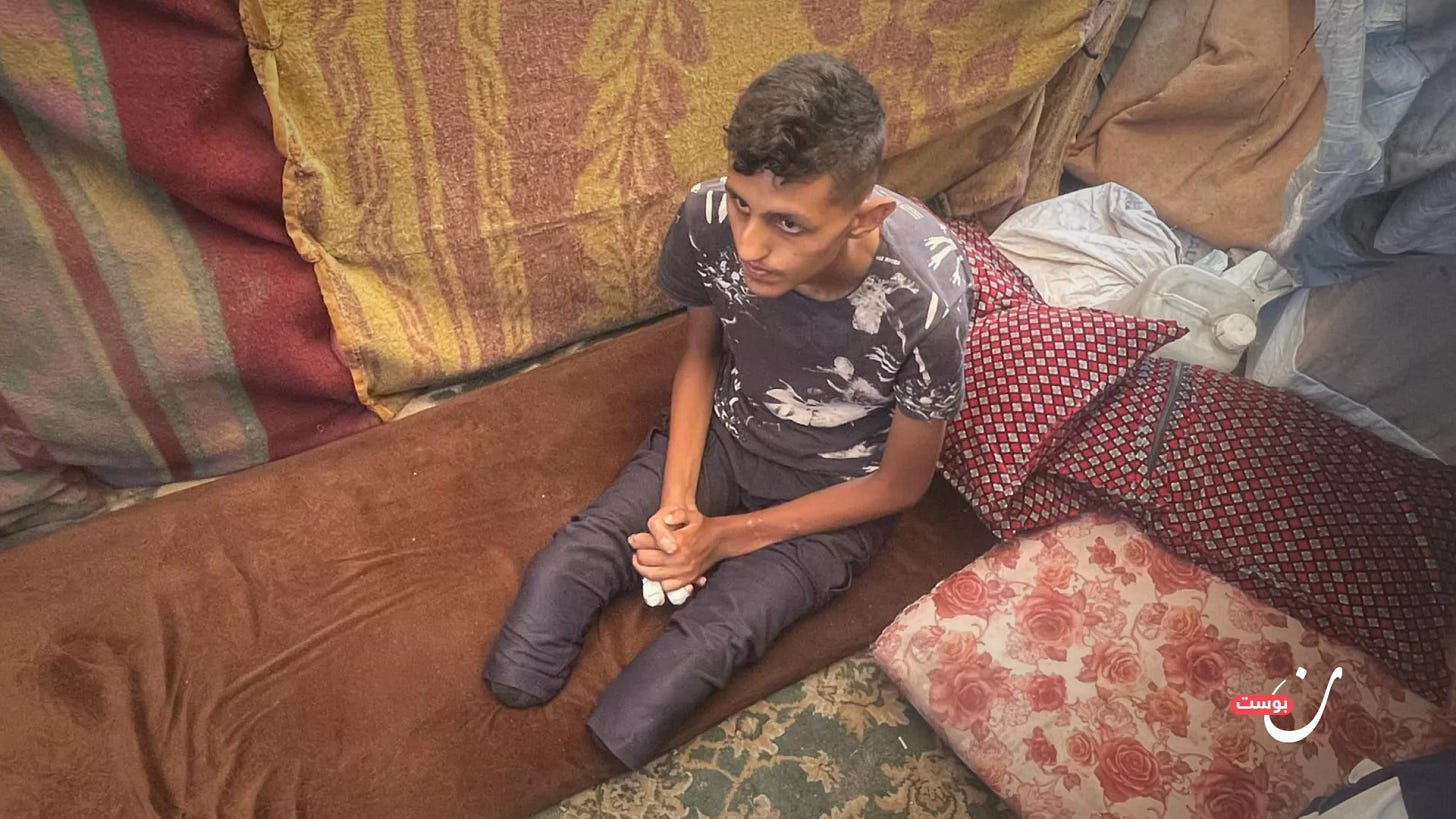

Twenty-year-old Hassan Nasr also lost both legs, forcing him to abandon his high school studies for two years. He now relies on his family for even the smallest movement.

He remembers waking up drenched in blood, only to realize both legs were gone. For a year, he has suffered from lack of medicines and equipment. Israel has blocked the entry of raw materials needed for prosthetic production at Gaza’s Hamad Rehabilitation and Prosthetics Hospital.

“Losing the most important parts of your body is a catastrophe in itself. You can no longer walk naturally, study, go out with friends. All of it vanished when I lost my legs,” Hassan tells NoonPost.

He dreams of walking again, playing football, returning to school, going to the beach, and running through the streets. But even asking his family to take him to the bathroom sometimes feels too much to bear. He is now confined to his tent, fearful of airstrikes, and unable to flee in case of danger.

A Crisis Beyond Capacity

Dr. Ahmad Naeem, director of Hamad Rehabilitation and Prosthetics Hospital, says the war has triggered a more than 225% surge in amputations, with over 6,500 new cases since the conflict began—up from about 2,000 before October 2023.

The hospital can produce no more than 150 prosthetic limbs a year, meaning that at the current pace, it would take over 20 years to meet the existing need without a major expansion. The hospital now receives about 200 patients daily, ranging from rehabilitation cases and amputations to hearing and balance disorders.

Dr. Akram Mansour, Dean of the College of Education at the University of Palestine, describes the mental health situation for amputees as deeply complex. Reactions vary depending on the circumstances of the amputation and the support received.

Many, he says, are initially in shock and denial, hoping it is all a nightmare. They fear pity, bullying, and isolation. With proper psychological and social support, some manage to adapt and rebuild their lives—sometimes stronger than before. But others fall into post-traumatic stress disorder, severe depression, and chronic anxiety, which can lead to anger, withdrawal, and rejection of their reality.