It’s often said that history is written by the victors. It’s also said that history has two faces, and amid the swelling number of such sayings, the lines between fact and fiction blur. Readers and historians alike are left wondering where history begins, how it unfolded, and where it ends—turning history itself into a dialectical battleground demanding careful reflection.

In 1982, as a thirty-year gag order on Israeli archives was lifted, Benny Morris—a Cambridge-educated historian who identifies as a Zionist—saw an opportunity. For the first time since the 1948 Nakba, the vaults of Israel’s history opened. According to Morris, his motivation wasn’t ideological or political—it was simply “a desire to know what happened.”

For a decade, Israeli historians were granted access to troves of internal documents and transcripts related to the Nakba and its prelude. For the first time, some of them began deconstructing the foundational myths promoted by the Israeli state, edging closer to a narrative rooted in evidence rather than propaganda.

These archives became the raw material for studies that sought to reread the 1948 war—not through memory or mythology, but through the lens of the victor’s archive.

What stood out was not the volume or scarcity of documents, but the shock they delivered to certain historians—shaking their faith in their state’s narrative, the sanctity of its wars, and the moral foundation of its national existence. Confronted not by a political adversary, but by the Palestinian account as a historical mirror, a current of historical denial began to flow—swimming upstream against society, the state, and the Zionist establishment itself.

At this critical juncture, Benny Morris coined the term “New Historians” to describe this group of researchers breaking from the official narrative. Yet Morris himself would soon retreat, reinterpreting the archives in terms of “historical necessity,” shifting from “truth-teller” to apologist urging the completion of what was left unfinished.

This article, situated within the context of the Nakba, examines the true role of the New Historians—the sincerity of their revelations, their ideological positioning, and the actual impact of their admissions on the Palestinian cause and the image of “Israel,” both domestically and globally, in public discourse and academic spheres.

One Perspective Is Not Enough

With a population barely exceeding 650,000, the early Jewish settlers—returning from global diaspora—claimed to fulfill the Zionist prophecy of Aliyah. Within months of receiving international recognition to establish a “homeland” on part of their “promised land,” the nascent state of Israel, so the official story goes, was attacked by five standing Arab armies representing over 40 million people and more than 13 million square kilometers. Backed by Britain, these armies, it is said, sought to strangle the newborn state and drive its people into the sea.

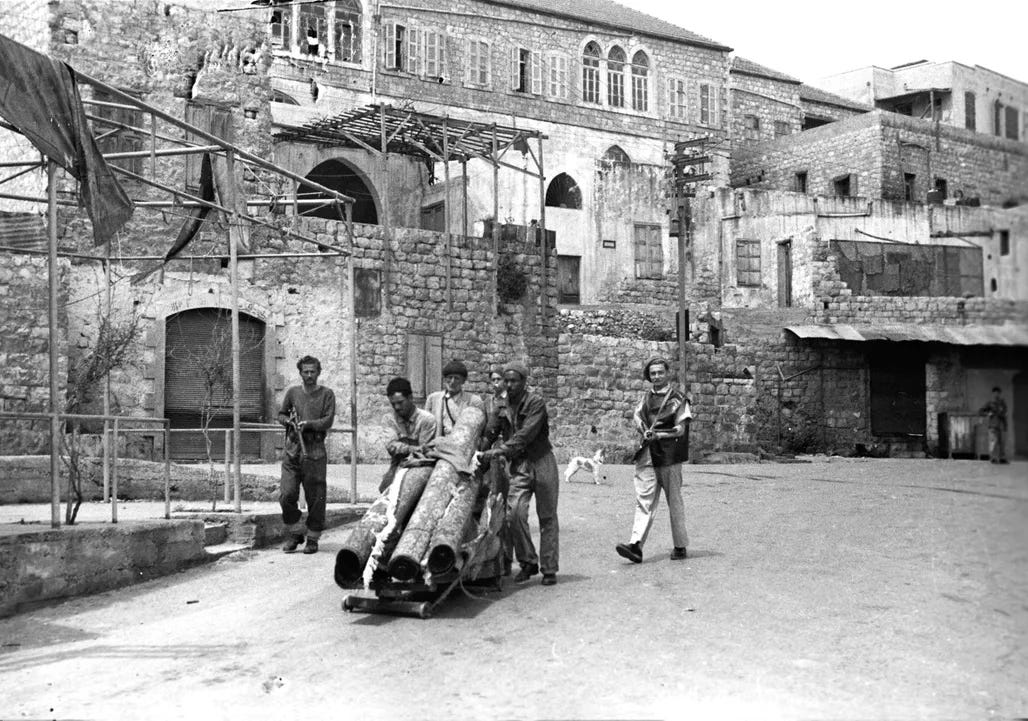

Palestinian Arabs were allegedly encouraged to temporarily leave their villages, making way for the “gathered armies” to use overwhelming force—until the small Jewish population rose, David-like, to defeat the Goliath in a mythical victory.

This was the canonical Israeli narrative of the 1948 Nakba, repeated in textbooks, speeches, and media for decades—until the early 1980s, when the Israeli archives were opened, revealing layers far more complex than this sanitized tale.

At that moment, Israeli sociology began to turn inward. A new intellectual and academic movement emerged: Post-Zionism. It called for a reexamination of Zionism itself and questioned the viability of a Jewish ethno-nationalist state on Palestinian land. This movement also probed the role of academia, film, art, and literature in constructing and justifying Zionist identity and national consciousness.

Among the most influential figures in this shift were the so-called New Historians—a loosely affiliated group of Israeli scholars who confronted the archival record independently. They include Benny Morris, Ilan Pappé, Avi Shlaim, Simha Flapan, and Tom Segev. Each, in their own way, set about interrogating the Zionist narrative of the Nakba through long-buried official records.

Benny Morris’s 1987 book The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949 was followed by Ilan Pappé’s Britain and the Arab–Israeli Conflict, 1948–1951 in 1988, and Avi Shlaim’s Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine that same year. Simha Flapan published The Birth of Israel: Myths and Realities in 1987, while Tom Segev’s 1949: The First Israelis came out in 1986.

These five works leaned almost exclusively on the Israeli archive. Through meticulous detail, they dismantled the dominant narrative surrounding the Nakba and exposed the glaring contradiction between what actually transpired and what had been promoted for decades—that Palestinians left of their own volition.

Yet these revelations, celebrated in the West as marks of “intellectual bravery” and “archival breakthroughs,” were structurally flawed. Despite their apparent candor in challenging official history, most New Historians maintained a calculated neutrality—avoiding explicit legal terms or direct moral condemnation.

They often substituted terms like “forced expulsion” with softer language—“evacuation,” “necessary military procedures,” or “temporary security needs.” Except for Pappé, most treated the Nakba not as a premeditated campaign of ethnic cleansing, but as a result of miscalculations or battlefield chaos, rather than political intent.

The deeper methodological issue in their work lies in their near-total reliance on Israeli sources—military, governmental, and intelligence archives like those of the Haganah and the Israeli Foreign Ministry. As a result, their texts ultimately reaffirm a one-eyed history: the victor’s account, devoid of the victim’s voice, stripped of the long-term consequences and broader structural context of the crime.

Benny Morris has openly stated his refusal to rely on Palestinian oral histories—despite their foundational role in Palestinian historiography—deeming them unreliable and biased. “I write military and political history based on documents,” he once remarked, “not on folklore.”

Even Ilan Pappé, in his groundbreaking 2006 book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, only lightly incorporated Palestinian sources, failing to apply a rigorous methodological framework or treat them as equals to Israeli documents. Instead, these narratives served a supporting role, reinforcing a broader story still rooted in the state’s own archive.

Meanwhile, Avi Shlaim, Simha Flapan, and Tom Segev largely remained within the boundaries of Israeli archival sources, occasionally branching into Israeli and Western media or foreign diplomatic files, but completely ignoring Palestinian oral accounts or Arabic written sources—suggesting an implicit belief that truth resides only within the state’s official record.

In subsequent years, more scholars joined this trend—Shlomo Sand, Baruch Kimmerling, Uri Ram, Uri Avnery, Gershon Shafir, and Adi Zertal—yet their work, too, remained anchored in Israeli archives. Their critiques reworked the Zionist narrative without questioning its epistemological center, aiming for more “accurate” and “less propagandistic” versions that sparked domestic debate but stopped short of genuine historical reckoning.

While these studies were crucial in challenging official accounts and confirming the forced displacement of Palestinians, they also revealed a profound epistemic bias. As Edward Said observed, Palestinian truths were only taken seriously when validated by Israeli historians—and even then, only as corroborated by Israeli sources, not from a genuine engagement with the Palestinian perspective or its possibly greater fidelity to lived experience.

The missing question in all their work remains: What if Palestinian oral history is more truthful than the written archive? Palestinian historian Nur Masalha offers a sobering reminder: “History must not be the sole domain of the victors.”

An Archive That Does Not Apologize

Over the lifespan of the New Historians’ movement, more of Zionism’s concealed chapters were uncovered. But as this revisionist current grew, the Israeli establishment began to perceive a threat to the carefully cultivated image of the state. By the early 1990s, the government initiated a policy of “re-closure,” led by the secretive Malmab unit—a division of the Ministry of Defense responsible for safeguarding classified material.

Under this plan, tens of thousands of previously declassified documents were withdrawn, under the pretext of “reclassification.” These included documents that could damage the image of the state, weaken the military’s prestige, or reveal sensitive intelligence operations.

In 1998, when the oldest Shin Bet and Mossad files were due for release, both agencies requested to extend the secrecy period from 50 to 70 years. In 2010, the duration was officially extended, and by February 2019, it was raised to 90 years—despite opposition from Israel’s highest archival council.

Meanwhile, the New Historians stuck to their hallmark style: partial confessions riddled with justifications, and critiques devoid of legal terminology. This rendered their work largely ineffective as admissible evidence in international forums of accountability. Domestically, their findings had minimal impact—failing to alter state policies, penetrate educational curricula, or foster widespread public re-evaluation of Zionism’s roots.

Their influence was more pronounced in Western academic and activist circles—thanks to publishing in English and connections to left-leaning institutions—contributing to a broader awareness of the Palestinian plight. But fundamentally, Israeli revisionist historiography has served Israel more than it has served Palestine.

It offered a softened, humanized, sanitized narrative—one that seeks to “understand” rather than indict, framing the relationship between aggressor and victim as a tragic misunderstanding, not a foundational crime.

Indeed, this internal critique is sometimes wielded to bolster Israel’s image as a vibrant democracy—where citizens can freely criticize the army, government, and even the state’s founders. The Nakba is thus reduced to a regrettable misstep in an otherwise noble national journey—not a crime demanding justice and redress.

From an Arab perspective, scholar Khaled Hroub describes Arab intellectuals’ reactions to the New Historians as ranging between cold approval and outright skepticism. There is a widespread belief that this body of work is less an effort to correct historical injustice than a therapeutic exercise in assuaging Israeli guilt and absolving the collective conscience.

Others argue that the New Historians should bear direct moral responsibility for the atrocities they reveal. Palestinian historian Abdel Qader Yassin put it bluntly: “If the New Historians were truly sincere in their recognition of the crimes committed against Palestinians, they would have left Israel the moment they discovered the full horror of what their forefathers did.”

Similar sentiments are echoed by Ibrahim Khalil Al-Allaf, head of the Arab Homeland Studies Center, and novelist-critic Hamza Mustafa, who liken the dispute between the New Historians and their orthodox peers to “a quarrel among thieves over how to divide the spoils”—a dispute over the loot, not the legitimacy of the theft.

Lebanese academic Clovis Maksoud contended that the so-called Post-Zionism and New Historians phenomena amount to a cosmetic facelift for Israel’s narrative—an attempt to align with global intellectual trends and find an elegant exit from the moral quagmire exposed by the 1982 Lebanon invasion, the First Intifada in 1987, the Al-Aqsa protests of 1996, and the Second Intifada that followed.

But the years that followed exposed the hollowness of many of these efforts. Some of these historians, most notably Benny Morris, veered sharply right. Once considered a critical voice, Morris devolved into an openly racist ideologue, describing Arabs as belonging to “a tribal culture lacking moral restraints,” and calling, after 2000, for Palestinians to be placed “in a cage.”

“I know that sounds terrible. It’s really harsh,” he said, “but there is no other choice. There is a wild animal that must somehow be locked up.”

Even before his full rightward turn, Morris had failed to uphold even a basic ethical recognition of Palestinian rights. He rationalized their suffering as a tolerable cost: “The catastrophe that befell the Jews under Nazism was worse than what happened to the Palestinians.

One could argue that by settling here, we saved the Jews from future catastrophes. On that basis, the injustice inflicted upon the Arabs can be justified.”

Tom Segev, meanwhile, never abandoned the Zionist framework. “As long as peace remains unachieved,” he stated, “Zionist ideology will continue to guide the Israeli state. Until then, we cannot see ourselves in a post-Zionist phase. Zionism remains a security necessity.”

More flexible were Ilan Pappé and Avi Shlaim, both of whom relocated abroad without renouncing their Israeli citizenship. From outside the state, they pursued critical scholarship opposing Zionism and highlighting the continuity between the original Nakba and its contemporary iterations—from ethnic cleansing to systematic displacement. Their stance led to their ostracization in Israeli society, branded as “self-hating Jews.”

In the end, many of the Israeli “confessions” once celebrated by Arab observers were not courageous acts of reckoning, but tactical maneuvers—exposed for their fragility as soon as tensions escalated. When push came to shove, the original narrative returned, now more brutally honest in its racism and violence.

Ultimately, the revolutionary promise of the New Historians—though valuable at certain moments, especially amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza, the Israeli government’s accelerating extremism, and the global decline of justice and human rights—has borne fruit only in the West’s academic backyards. There, their work circulates as scholarly papers and theoretical debate, not as instruments of legal or political accountability.

Inside Israel, the dominant mentality—both official and popular—still refuses to extricate the Nakba from the framework of the “War of Independence.” It is not recognized as ethnic cleansing or forced expulsion. Even when evidence is presented, it is framed as the “harsh necessities” endured by the founding generation to achieve “stability,” not crimes deserving justice.

Thus, after the collapse of Israel’s left and the near extinction of its influence, the New Historians have become a token voice—maintaining a façade of “pluralism” in the prevailing narrative. Their impact rarely leaves the confines of academic bookshelves. It does not permeate politics, education, or public consciousness.

As Mahmoud Darwish once wrote, “And I bleed memory as I bleed,” the Palestinian holds vast reserves of memory—laden with emotion, pain, and defiance. Yet all too often, this memory is used as fuel for despair, not as a political or legal bridge to accountability. Not even as a tool for resistance or disruption. Sometimes not even to scream back at the oppressor: We are still here.

Yes, Palestinians have memory. But what shackles it is the complex of the defeated—who, despite everything, still seeks to hear his history from the colonizer’s mouth.