How Do We See Our Cities in Zafón’s Novels? A Conversation with Translator Muauia Abdulmagid

Literary translation is far more than the transfer of words from one language to another. It is a rigorous journey through meaning, memory, and style. When a literary text crosses linguistic boundaries, it brings with it a dense human experience a city layered with history and unresolved questions of violence and destiny.

This is where the work of Syrian translator Moawia Abdelmajid stands out: it reflects a deep sensitivity to place and memory and an understanding of literature as a lens shaped by readers’ experiences and contexts.

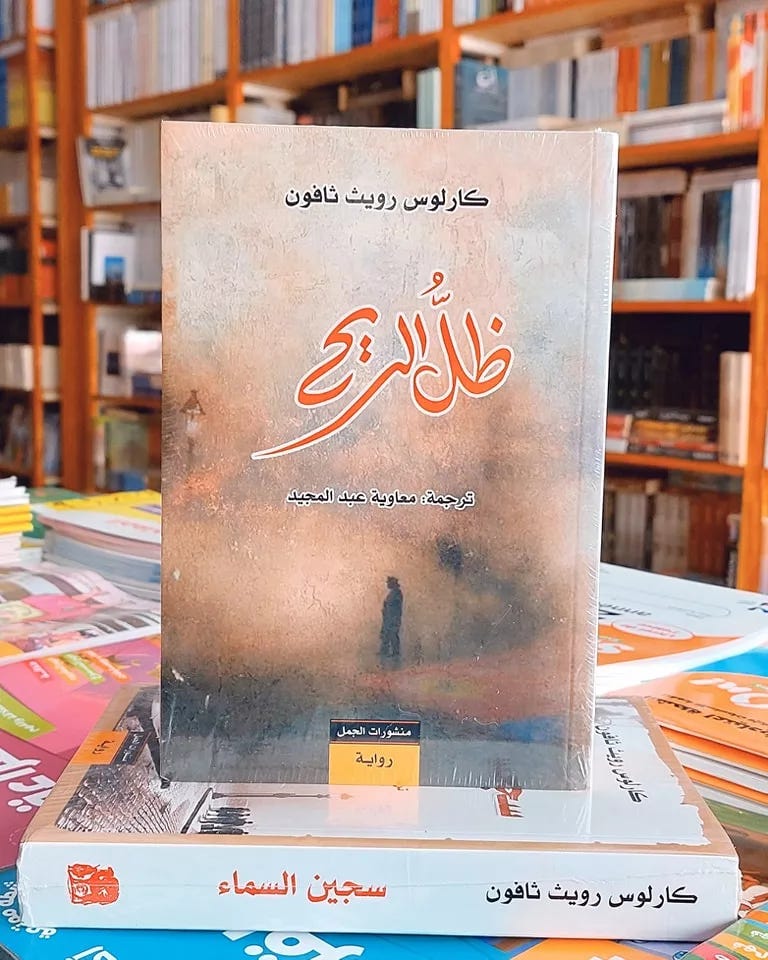

Arab readers came to know Abdelmajid through his translations of the late Spanish author Carlos Ruiz Zafón, most notably The Shadow of the Wind, the first in the Cemetery of Forgotten Books series. Abdelmajid’s Arabic rendition preserved the density of the narrative and symbolic depth of the original, while inviting comparisons between geographically distant but spiritually kindred cities.

Zafón’s Barcelona steeped in tunnels, memory, censorship, and violence felt deeply familiar to many Syrian readers. Not as a direct reflection, but as a shared human experience of tyranny and ruin, evoking Damascus, Aleppo, or Homs.

In this interview with Noon Post, Moawia Abdelmajid offers a rare glimpse into a translation journey that spanned years. He discusses literary translation as a meticulous balancing act between fidelity and creativity, linguistic choices dictated by Zafón’s layered prose, the Syrian reader’s relationship to the works, and the role of translated literature in a post-war context a time when cities, memory, and identity are once again pressing questions.

We aim, through this conversation, to approach translation as a cultural act and literature as a space to understand the self through the other in a time when the great questions of memory and meaning remain wide open.

Let’s begin..

- What first drew you to Zafón’s writing?

Was The Shadow of the Wind a natural starting point, or did you arrive there differently?

The Shadow of the Wind was a difficult choice, but indeed the natural gateway into Zafón’s world. He had written four novels before it, all well-received and primarily targeting young adults. But with The Shadow of the Wind, Zafón decided to reach a wider audience beginning with young readers but extending to older ones as well.

The novel tells the story of a young boy who discovers the pleasures of reading through a mysterious book, leading him to uncover the story of its author and the world that shaped it. This resonates with young readers and older ones alike, especially those who remember the thrill of their first transformative book.

Add to that the rich social dynamics, the neighborhood characters, love stories, and a strong cultural-political undercurrent that runs unmistakably through the narrative.

Once I began translating The Shadow of the Wind, I knew I had to continue with the entire Cemetery of Forgotten Books series. I went on to translate The Angel’s Game, The Prisoner of Heaven, and The Labyrinth of the Spirits. When his complete short stories were posthumously published under City of Steam, I translated that too, as it carried the same atmosphere of Barcelona.

I eventually returned to Zafón’s earlier novels The Prince of Mist, The Midnight Palace, The Watcher in the Shadows, and Marina.

In short, all of Zafón’s works are now available in Arabic. But it all began with The Shadow of the Wind, a novel that profoundly shaped its author, its readers and its translator.

- Zafón’s language moves between tightly plotted narrative and poetic, symbolic prose.

How does a translator maintain both precision and rhythm, especially when facing metaphors that defy literal translation?

Naturally, a translator must inhabit the author’s rhythm, particularly when the writing shifts pace and tone to mirror the author’s imagination. Thankfully, Arabic is a literary language, rich in expressive tools that can be employed to navigate such challenges.

Some readers believe that literal, word-for-word translation ruins the Arabic text. That’s not always true. In some cases, literal translation solves structural problems and eliminates clumsiness that would otherwise alienate the Arabic reader.

Literary translation, however, is ultimately about interpreting the author’s stylistic intent: why is a sentence fast-paced, emotional, suspenseful? Why is another more contemplative? The translator must grasp these choices and convey them.

The real challenge is style and whether the translator preserved the original voice, making it accessible yet rich for the Arabic reader. Did I enhance the style to make it compelling in Arabic, or did I dilute it?

Beyond such questions, the translator bears a deep responsibility. Literature is a window into the lives of individuals and societies, yes, but it is also a mirror of emotional expression. In Zafón’s work, when characters enter the Cemetery of Forgotten Books, they are stunned, speechless. Arabic must rise to the occasion to convey that mythical atmosphere.

Was there a scene or passage in The Angel’s Game, The Labyrinth of the Spirits, or The Shadow of the Wind that you found especially difficult one that you felt could only be translated through radical rephrasing?

Absolutely. Many passages required multiple rewrites. Thank heavens we work on computers otherwise my house would be buried under torn paper.

Take this scene from The Shadow of the Wind, where Daniel describes the opening of the Cemetery gates:

“The gears moved like a robot, emitting a thunderous click that set off a series of pulleys dancing in a strange mechanical ballet, intersecting with a network of steel rods embedded in wall slots.”

I must have translated and re-translated that sentence six times before it felt right.

In The Angel’s Game, there’s a description of Sempere looking at David Martín: “He stared at me on the verge of a look filled more with worry than comfort.” This required a creative, almost poetic rendering: “Sempere was staring at me on the edge of a glance of worry.”

Another example, also from The Angel’s Game, involved preserving Zafón’s exact structure:

“The headquarters’ facade, seen from a distance, merged with family tombstones scattered across a skyline pierced by chimneys and buildings clumped under a black-and-scarlet eternal sunset over Barcelona.”

It’s one long sentence with no commas. Why? Because the author wants the reader to feel overwhelmed, visually and emotionally, just as the character is. Punctuation would clarify the view but Zafón wants it to blur.

I could cite dozens of such moments in every chapter, hundreds in each book. Scenes like Fumero’s confrontation, Martín’s lover’s death in the lake, every visit to the Cemetery, Fermín’s escape from prison and his magical return in The Labyrinth of the Spirits, Isabel’s jokes and Fermín’s wit the list goes on.

Would you say the Syrian reader’s connection to Zafón is more of a “mirror” than a simple translation seeing Damascus, Aleppo, or Homs in Zafón’s Barcelona?

I can’t speak for “the Syrian reader” in general. But for myself, yes. I felt that Zafón’s portrait of Barcelona’s soul reminded me of Aleppo’s spirit, its labyrinths evoked Damascus’s alleyways, its siege echoed the pain of Homs. I imagined a Syrian novelist crafting such a story in our own setting.

But what we lack is literary craft. The elements are there place, time, events. What’s missing is the novelistic technique to weave them into enduring fiction.

Interestingly, in City of Steam, Zafón writes of a traveler who survives by telling stories to pirates who want to throw him overboard. He learns to leave them wanting more, as an old Damascene storyteller once told him: “They will hate you for it, but they’ll crave you all the more.”

How could I not think of Assad’s henchmen when reading about Fumero, or the Nazi-like bombing campaigns that ravaged nearly all of Syria? Censorship, repression, corruption, torture these are real. I even used the term “shabih” (regime thug) in The Labyrinth of the Spirits.

Still, The Shadow of the Wind is a translated novel, not a mirror. But it is a fable: that tyranny fades, oppressors fall, and the people remain.

- Literary translation has historically opened intellectual horizons and challenged narrow identities.

How can it help Syrians in the post-war period move beyond sectarianism and toward a unifying national discourse?

I think Syrians today are scrambling to piece together a sense of identity often in chaotic ways. I don’t believe they are currently seeking wisdom from the experiences of other nations. Syria’s trauma is unique.

That said, we must avoid reinventing the wheel. But I fear we are heading toward even greater isolation, desperate to frame our discourse as inclusive and national, at any cost.

Spain endured a civil war. Syrians still reject describing their revolution that way. And if you examine the great revolutions of history many of which passed through sectarianism and tribalism you’ll find it’s hard to draw parallels to Syria, or expect similar outcomes, at least in the near term.

So yes, the unified national narrative must emerge from within the Syrian experience. Comparisons to other contexts risk being little more than cultural illusions. Translation won’t do more than that. That’s not criticism or praise. It’s simply an observation.

But such a narrative is urgently needed. It’s not a luxury or a decorative layer. It’s a foundational necessity.

Do you think Syrian readers, once peace is restored, will be more open to global literature that reminds them Syria’s tragedy is part of a larger human story like Zafón’s novels that link memory with destiny?

Yes, I think Syrian readers will be more willing to compare global experiences with their own. They may ask: why did certain societies succeed where we failed?

You mentioned the “larger human story.” And it’s worth noting: despite the diversity of European languages, their literature rarely contradicts the West’s overarching humanist values. Literature often trains readers to reject racism and fascism, and to value freedom and empathy from romance novels to detective stories.

Zafón’s writing affirms this worldview. His links between memory and fate are part of that narrative: a past of fascism and racism, a turbulent present, and a hopeful future built on respect and liberty.

Our challenge is to insert our own experience into that broader story. It’s complex, difficult, and full of obstacles. But it’s the only way to truly benefit from others’ journeys and to share our own.