When Malcolm X set foot in Mecca in 1964, he was not just a pilgrim fulfilling a religious obligation—he was a man burdened with anger, carrying the weight of a lifelong struggle for justice. He believed that racial segregation and division were an inescapable destiny. But the pilgrimage changed everything within him.

Malcolm’s Hajj was a profound turning point that reshaped his worldview, broadened the scope of his activism, and granted him a deeper, more human vision of the world. His pilgrimage diaries stand as a rare and powerful document chronicling the seismic shift in his thinking—offering insight into his evolving perceptions of race, religion, and politics.

He had planned to publish these reflections as a separate book, distinct from the autobiography co-written with Alex Haley. Fate, however, did not grant him the time. Decades later, one of his daughters fulfilled his wish by publishing his Hajj diary in 2014.

What Led Malcolm to the Hajj?

Born in 1925 in Nebraska to a poor family that fought for Black rights, Malcolm experienced a childhood marred by brutal racism. His father was murdered by white supremacists who burned their home; his grandmother was raped, and his mother was institutionalized due to repeated racist abuse and trauma.

Shuffled between foster homes, Malcolm—despite his intelligence—faced relentless racism at school, including from teachers who mocked him. He dropped out in the ninth grade after an English teacher told him becoming a lawyer was unrealistic for a Black boy, advising him to pursue a “Negro job” like carpentry.

His difficult youth and troubled early adulthood hardened his resentment toward white America. Drawn into a life of crime, he sold drugs and burglarized wealthy white homes until he was arrested in January 1946 at the age of 20 and sentenced to ten years in prison.

While incarcerated, he initially continued his rebellious lifestyle, earning the nickname “Satan” for his profanity and open disdain for religion. Yet, he was searching for a way out. Immersing himself in reading and influenced by his siblings, he joined the Nation of Islam, led by Elijah Muhammad.

The movement preached Black empowerment but also espoused racial theories incompatible with mainstream Islam. Still, Malcolm found in it a lens through which to interpret the oppression he had endured.

After serving seven years, Malcolm emerged as one of the Nation’s most charismatic and articulate spokesmen. Under his influence, the organization grew from a few hundred to thousands of followers, becoming a major force in the 1950s and early 1960s.

At the time, Malcolm’s rhetoric rejected any form of integration with white Americans. He believed everything associated with white society was inherently corrupt, dismissed Christianity as a tool of domination, and framed the white man’s heaven as the Black man’s hell. He even predicted an impending racial Armageddon.

In the early 1960s, Malcolm learned that Elijah Muhammad was not the moral exemplar or divine messenger the Nation claimed. Revelations of his affairs with young secretaries shattered Malcolm’s faith in the movement and prompted a decisive break.

In his autobiography, Malcolm recalls hearing that the Nation of Islam did not represent true Islam. This sparked his desire to experience authentic Islam and connect directly with Muslims. Hajj offered the perfect opportunity, and in 1964—just months after leaving the Nation—he embarked on the journey to Mecca.

From America to Mecca

He approached his sister Ella for a $1,300 loan to fund the pilgrimage. She agreed. After saying goodbye to his family, Malcolm flew to Cairo in early April 1964. At Cairo airport, he was advised to leave his camera behind before continuing to Jeddah.

In Cairo, he purchased a small suitcase that barely fit one suit, a shirt, some underwear, and a pair of shoes. As he joined a group of pilgrims heading to the airport, he felt nervous, realizing he would have to learn the rituals by observing others.

Clad in the simple white garments of ihram, he was moved by the crowds chanting in unison: “Labbayk Allahumma Labbayk.” He saw people of all colors embracing one another with warmth and affection, and for the first time, he felt as if he had emerged from a lifelong prison.

Malcolm wasn’t originally on the manifest for the flight to Jeddah. But in a special gesture, one passenger was bumped to make room for him. Malcolm felt guilty but also deeply humbled and grateful for the respect shown to him as an American Muslim.

He described the plane as filled with passengers of all races—Black, white, Asian. When word spread that an American Muslim was among them, smiles and greetings flowed freely. Even the Egyptian pilot invited him to visit the cockpit, which Malcolm did gladly.

At Jeddah airport—busier than Cairo’s—the pilgrims were divided into groups, each assigned a guide who would accompany them to Mecca. As he moved through the throngs, the chants of “Labbayk” echoed all around.

Malcolm described seeing pilgrims from Ghana, Indonesia, Japan, and Russia, writing in his autobiography, “I doubt that the most skilled Hollywood cameras have ever captured a human spectacle more colorful than what my eyes witnessed.” He likened the moment to pages from National Geographic.

In the Sacred Cities of Mecca and Medina

Malcolm was hosted by Prince Abdullah bin Faisal, who gave him the finest suite in the Jeddah Palace Hotel and offered every resource to help him understand Islam. A car, driver, and translator were placed at his disposal. He later wrote that he had never experienced such sincere hospitality and brotherhood.

While exploring Jeddah, he noted the absence of entertainment venues—no clubs, theaters, or cinemas—yet the city was clearly expanding, with modern buildings and roads under construction.

Upon seeing the Kaaba, surrounded by thousands of pilgrims, he was overwhelmed with joy and pride. Standing shoulder to shoulder with people of every race and color, he experienced no discrimination, no suspicion, no hatred.

For the first time, Malcolm realized the world need not mirror America’s racial division. Racism, he saw, was a man-made construct. “In Mecca, for the first time in my life, I felt like a complete human being in the presence of my Creator,” he wrote.

He bought dozens of postcards and sent letters to friends and family in the US, describing his transformation. In a letter to Alex Haley dated April 25, he expressed that he had never experienced such genuine kindness and fraternity among people of diverse races.

The next day, Malcolm joined thousands heading to Mount Arafat. He stayed in a large tent, sharing meals with people who, in America, would be considered white—but whom Islam stripped of such labels. Witnessing this diverse and egalitarian gathering deeply moved him. He began to rethink his previous beliefs, embracing new truths he encountered on pilgrimage.

One night, while sleeping under the stars in Muzdalifah, Malcolm felt enveloped by a profound sense of unity. He was told this was the largest Hajj in history. Turkish MP Kasım Gülek informed him that over 50,000 pilgrims had come from Turkey alone. Malcolm dreamed of the day when African American Muslims would flock to Mecca en masse. He wrote in his diary:

“In Muzdalifah, we completed our evening prayer, gathered the seven stones for tomorrow’s stoning ritual in Mina, then ate and talked… I’m growing used to these customs: eating with my hands from the same dish, drinking from the same cup, bathing from a small pitcher, sleeping on a simple mat under the open sky, listening to pilgrims snore from every corner of the earth.” (p. 31)

Throughout the Hajj, Malcolm engaged with Muslims of varied backgrounds, gave speeches, and conversed with African pilgrims and notable figures, including Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husseini, Mecca’s mayor Abdullah Arif, and Sheikh Surur al-Sabbaan. He shared with them the plight of Black Americans, emphasizing how skin color alone could subject a person to violence and oppression in the US.

On April 24, Malcolm completed the rites of Hajj, departed Mina, and flew the next day to Medina. Though the government had arranged for an escorted car ride, he opted to travel alone by air to avoid a five-hour drive. On the flight, he continued documenting his thoughts, writing about an inner peace he hadn’t felt in years.

In Medina, he stayed at a hotel overlooking the Prophet’s Mosque. The locals were astonished to meet an American Muslim, treating him with admiration and respect.

He described Medina as an oasis of peace and tranquility, befitting the Prophet of Mercy. After performing the evening prayer in the mosque, he was overcome by a unique sense of serenity. He called Medina the most peaceful place he had ever visited and felt closest to God there. He also visited the local market and purchased several rings.

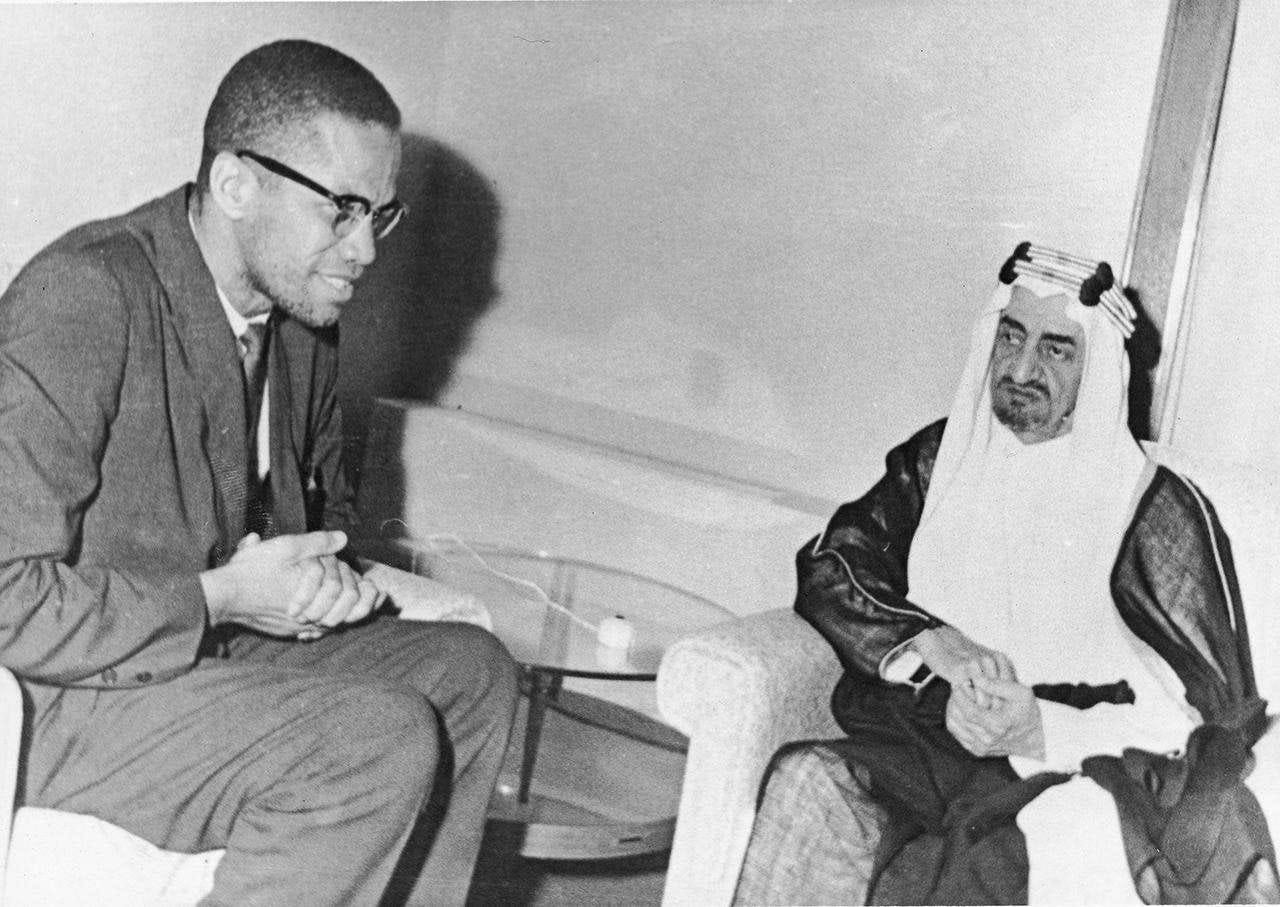

As Malcolm prepared to leave Saudi Arabia, he received a call from Prince Faisal, urging him to delay his departure to allow for a personal meeting the following day. Malcolm gladly accepted.

During their meeting, Malcolm explained his work organizing Black Muslims over the past twelve years and said his aim in making the Hajj was to discover the essence of true Islam. Faisal praised his journey, telling him, “That is a good thing.” When Malcolm fumbled to express his gratitude, the prince reassured him: everything was done in the spirit of Islamic brotherhood.

On April 29, Malcolm left Jeddah for Beirut, seeking to learn more about the Muslim Brotherhood. He then embarked on a regional tour through Egypt, Sudan, Algeria, Ghana, and Gaza—where he expressed solidarity with the Palestinian people and highlighted the racial injustices faced by African Americans.

How the Hajj Reshaped Malcolm’s Worldview

In two transformative weeks, the Hajj revolutionized Malcolm’s beliefs. His only regret was not knowing Arabic. Nevertheless, the experience left him with indelible memories and emotions. He considered himself the first African American to complete the Hajj.

The pilgrimage not only altered his personal beliefs—it redefined his understanding of identity, race, and the path to justice. He adopted an Islamic, post-racial approach to civil rights in America. His diaries make the contrast between pre-Hajj and post-Hajj Malcolm crystal clear. He wrote:

“My mind has never been more at peace or clearer. Since leaving Mecca, my thoughts have gained strength and focus… After this Hajj, any trace of racial judgment within me has dissolved. I’ve resolved to devote myself to living as a true Sunni Muslim.” (p. 140)

The Hajj helped Malcolm reconcile with himself and release the anger he had long carried. He let go of his belief that white people were inherently evil. The sacred journey shattered his old conviction that racial harmony was impossible. He transformed from an advocate of Black nationalism into a champion of human unity and brotherhood—having witnessed in Mecca a living model of racial transcendence.

Malcolm believed America could learn from Islam, the only faith capable of eradicating racism at its root. Upon returning, he quickly published an open letter to newspapers expressing his transformed view, particularly regarding white people. He called for reconciliation between Black and white Americans and voiced hope for a better future—signing his name: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

Soon after, he founded a new organization reflecting his evolved vision, which rapidly attracted followers and influenced the broader civil rights movement. But his journey ended tragically. On February 21, 1965, at the age of 39, Malcolm X was assassinated while addressing supporters in Harlem. Three gunmen shot him 15 times.