Since the start of Operation Al-Aqsa Flood by the Israeli occupation forces on October 7, 2023, up to early 2025, approximately 69 percent of Gaza’s buildings have been destroyed, according to a UN satellite assessment (UNOSAT).

Day after day, the devastation grows—and official figures likely understate the truth. In May 2025, an Israeli soldier captured footage in Rafah, southern Gaza, showing the city in near-total ruin, with just one house still standing.

Reconstruction of Gaza is projected by the United Nations to take around 15 years, at a cost estimated between USD 30 and 53 billion. Yet Palestinians—ever resilient—have previously astonished the world by reusing rubble from destroyed buildings to construct homes anew.

It’s as though they echo an ancestral folk song—sung before the Nakba of 1948—as their elders built homes:

“O our home, we shall build you tall and proud…

With our swords we shield you from every approaching danger, O protector…”

In this refrain, “O protector” (يا واو) is not merely poetic—it stands for the jackal, a symbol of lurking menace; “from every approaching danger” asserts a defiant promise of protection. Palestinians, it affirms, will raise their homes and guard them with swords against any threat.

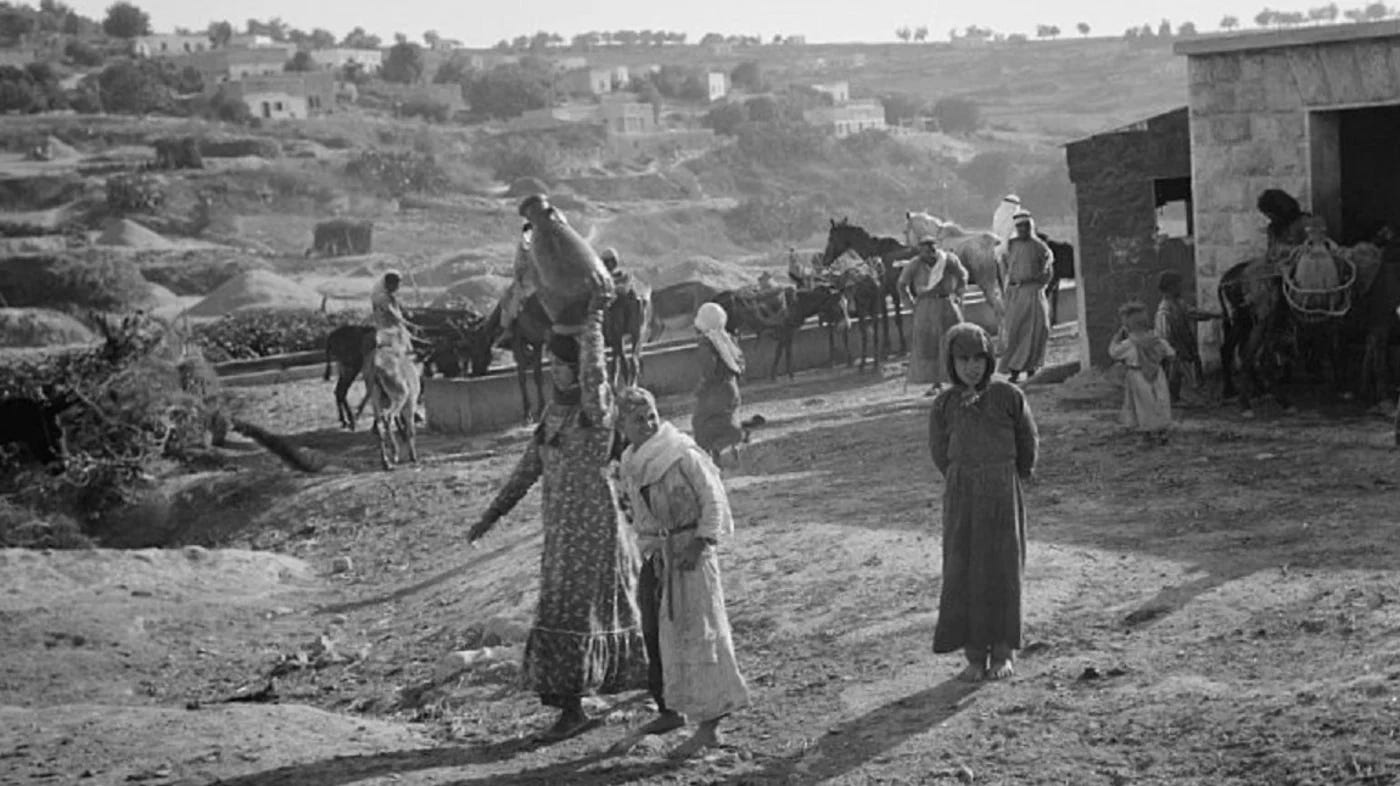

And why not? Pre-1948 Palestinian homes embodied self-sufficiency. Crafted from local materials—clay, stone, wood—they reflected faith, joy, community life, and rich traditions.

More than structures, these homes were social and spiritual creations, woven into community gatherings and religious customs. Eyewitness accounts and scholarly works—such as the late Tofig Kanaan’s “The Palestinian Arab House: Its Architecture and Folklore” (1964), Gustav Dalman’s “Work, Customs, and Traditions in Palestine,” along with Antonin Gossen’s studies on Nablus and Moab—document these homes in detail.

Below, we explore how the Palestinian farmer built his house from local resources, turning humble construction into a source of pride, spiritual celebration, and communal connection.

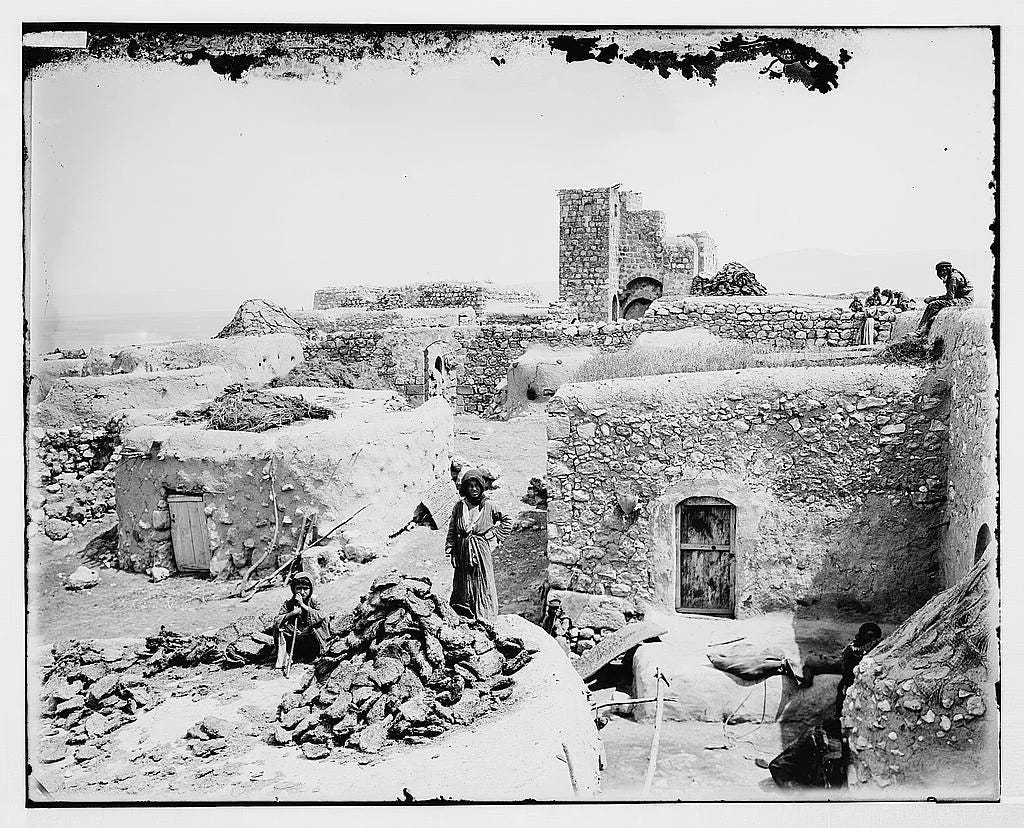

The Rural Palestinian House

Community-built simplicity: Rural homes were built with the direct labor of the farmer, his children, neighbors, and relatives. Even when a professional mason was hired, the homeowner's own hands remained involved.

Water management: A trench was dug around the house to channel rainwater into a well. Roofs, made of wood and brush with a clay‑straw mix, required annual maintenance—a challenge during winter rains.

Roof life: Birds sprouted grass—or even wheat—on these roofs, though the plants soon withered.

Colorful metaphors: Farmers joked that their four walls were like “four thieves wearing caps” or “four corpses carrying a corpse” (the heavy roof), while the creaky door was likened to a hung man crying out in vain.

Support structures: Roofs were sometimes held up by interior wooden or stone pillars—or built directly onto the walls.

Ventilation and light: Windows were rare, to deter thieves. Small openings near the roof—called “ṭāqāt”—provided air and allowed cooking smoke to escape; doors often stayed open during the day.

Villagers warned that cold blasts through a “ṭāqa” could be brutal—some even said, “Better to sleep outside than beside a drafty opening”—so farmers boarded them up in winter.

Interior layout: Most rural homes had one or two stories, with a single ground-floor bedroom, a small hall, and sometimes an extra room. A rooftop room called the “ʿuliyya” might be added—accessed by ladder, often opening onto a balcony.

Bathrooms were absent in many. Basic chamber pots were used indoors, while needs at night were taken care of behind the house. Urban homes, by contrast, typically featured bathrooms.

The courtyard world: A spacious front courtyard featured a shaded “maṣṭaba” (bench) under trees and trellised roofing, often accompanied by a large shade tree nearby. Nighttime summer respite came under these beams.

Courtyards also held a chicken coop, livestock pen, straw storage, cooking hearth, and traditional oven—all enclosed by a low wall, crafting a self-contained microcosm reflecting interdependence with the land.

Local Materials—From Land to Home

Materials depended on wealth and local environment:

Stone construction: In Jerusalem and hill areas, farmers used local rock. Large slabs were sometimes blasted with explosives, then shaped with primitive tools crafted by blacksmiths—axes, picks, adzes, chisels, levers.

Mud-brick building: In the coastal plain, red clay soil was mixed with water, molded, dried in frames, and sometimes baked in kilns for extra strength.

Mortar and plaster: Stone homes used lime mortar; mud-brick builders used red or yellow clay mixed with straw and plastered walls and roofs annually.

Stone houses also received lime-sand and marble-powder whitewash, reinforced joints, sealed with a blend of lime and indigo, and polished.

Woodwork: Timber from pine, oak, kermes oak, pistachio, cypress, hackberry—but not olive wood (too twisted)—formed beams and supports. Roofs in the north were flat, thanks to straighter local timber; in the south, curved roofs reflected scarcity of long beams.

Farmers harvested and prepared wood themselves, using simple tools; wealthier ones hired carpenters for structural features, doors, and windows.

Building Rituals: Sacrifices, Songs & Blessings

Building was steeped in ritual:

Foundation sacrifice: With the laying of the first stone or brick, a sheep was slaughtered and its blood let into the foundation trench—a ritual believed to ward off spirits and seek divine blessing. The meat was shared with family, laborers, neighbors, and the poor.

Regional traditions: In Northwest Jerusalem, builders laid the first stone on the southeast corner, invoked the name of God (“O God, O friend of God”), and recited Al-Fatiha; some communities performed this again on the threshold and read scriptural passages or used holy water and buried silver or gold.

Shadow superstition: Owners avoided letting their shadow cross the foundation stone—believing it portended death.

Protective charms: Christian builders stuffed items like eggshells, evil‑eye beads, garlic, glass shards, bright beads, bracelets, pomegranate seeds, and ostrich feathers over doors to guard against evil, or adorned them with crosses or verses (for Muslims), with the “Hand of Fatima” across faiths.

Ceremonial meals & songs: Neighboring folk joined the builders, sharing food and drinks. Celebratory melodies filled the air—chants like “Praise be to God, bless the Prophet!” and lyrical refrains celebrating the new home.

At completion, another sheep was sacrificed, a feast held, and another celebration if a rooftop room was added.

Roof tokens and blessings: On walls, farmers planted a white “flag of God”—a cloth tied to a stick—to be bleached by sun, wind, and rain, symbolizing lasting happiness; olive branches atop roofs promised long life and enduring faith.

Among Bedouins around Nabi Musa’s shrine, they sacrificed and anointed tent poles with blood for spiritual protection.

For the Palestinian farmer, building a home was more than construction—it was a testament to resolve, community, faith, and cultural identity. Crafted entirely from local clay, stone, wood, and straw, homes were raised with collective labor, spiritual rites, joyous songs, and heartfelt blessings. In simplicity lay profound strength: a home was built by hand, blessed by tradition, and held together by unity, pride, and the blessings of the land itself.