Sufism witnessed a widespread flourishing during the 11th and 12th centuries AH (17th–18th centuries CE), leaving a profound impact on pilgrims’ behavior. Visiting the tombs of saints became an integral ritual along the Hajj journey.

In this climate, Ibn al-Tayyib al-Fasi, one of Morocco’s most prominent scholars, set out to perform Hajj. Along the way from Fez to the Hijaz, he meticulously documented every incident, encounter, and emotion, composing numerous poems that reflected his spiritual experience.

Tragically, his writings were stolen along with his belongings in the town of Shu‘ayb in the Hijaz. What pained him most was the loss of his poems praising the Kaaba and the Prophet’s Rawda. He lamented, “If only the thief had returned a single poem I recited at the Holy Kaaba or the Noble Rawda, I would have forgiven him all my books and money.”

After departing the Hijaz and reaching Egypt, a close friend urged him to rewrite his journey and recapture the meanings behind the lost verses. Initially hesitant, he eventually found clarity after performing the prayer of istikhara and decided to rewrite his pilgrimage account, dedicating it to future pilgrims seeking guidance and inspiration.

Ibn al-Tayyib’s journey offers a rare and rich source for understanding the Hajj in the 18th century. It also carefully maps the routes Moroccan pilgrims commonly took to the Hijaz. Written in a unique blend of prose and poetry, his account holds a distinct literary charm.

Why did he go on Hajj?

Born in 1110 AH / 1698 CE in Fez into a family renowned for scholarship and literature, Ibn al-Tayyib studied under some of Morocco’s leading scholars. His writings reveal a deep appreciation for travel, which he viewed as a sacred obligation like Hajj—or at the very least, a blessed opportunity for learning and meeting scholars. He even considered writing an entire book on the benefits of travel.

His motivations for Hajj were manifold: a yearning to visit the Prophet, fulfill the sacred rites, seek knowledge, explore new lands, and meet fellow scholars. After ensuring provisions for his wife and children and receiving his parents’ prayers, he set off, well-equipped with warm and cold oils, kohl, salves, clothing, and books of poetry praising the Prophet. He also carried ink, pens, and paper.

From Fes to Cairo

He began his journey by visiting the tomb of Idris ibn Abdallah al-Kamil and the shrines of several imams near Bab al-Futuh, believing this would bless his path. He then joined a group of pilgrims heading toward “ʿUnq al-Jamal,” a treacherous, muddy road. When their camels faltered, they veered left to find safer ground.

Traversing mountains and valleys, Ibn al-Tayyib and his companions were warmly welcomed by tribes, who revered them as visitors of the Prophet. Their path led them through the arid lands of “al-Nakhila,” then up Mount Banu Majra, where nightfall forced them to camp at the summit.

By dawn, they descended and reached the city of Taza by midday. After a brief rest and visits to local shrines, they proceeded to Wadi Dabdou, with its fresh spring water, then to Wadi Belzouz, and on to the breathtaking Wadi Banu Mutahhar.

Next came “al-Naqoub,” a vast valley, followed by “Bayān al-Sultan,” a cluster of abundant wells, and then to “Aba al-Durūs.” After resting for their desert crossing, they moved on to “ʿAyn al-Hasna,” “al-Qusayʿat,” and “ʿAyn al-Hajar,” reaching the village of “al-Mashriyya,” known for its dairy and livestock.

There, Ibn al-Tayyib visited the shrines of Sheikh Muhammad al-ʿUmari, known as Mawlā al-Khalwa, and Sheikh ʿAbd al-Razzaq. They then reached Wadi al-Nukhayli, where the Fez and Sijilmasa caravans met, and continued through Wadi al-Tarfa to Wadi al-Ashbur.

Eventually, they arrived at “ʿAyn Madi,” famed for its sweet water and gracious people, then the bustling village of “Bakhmūt,” and on to Laghouat in western Algeria, where Ibn al-Tayyib met with scholars.

Their path continued to Wadi al-Hūt, then to the notorious village of Damat (or Wamad), known for banditry. Fear and thirst plagued them at ʿAyn al-Burj, but rain-filled valleys later brought relief.

Crossing Wadi Khalid ibn Sinan—known for its peril—they faced a severe windstorm that claimed the life of a pilgrim. “His fate overtook him before he reached his dream,” wrote Ibn al-Tayyib.

They reached Biskra on the 4th of Shaʿban, where he admired its beauty, met scholars, and visited saints’ tombs. However, he noted the city’s political turmoil—caught between Turkish incursions and Arab tribal raids.

Leaving Biskra, they visited the shrine of ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ, climbed the high Mount Musāmida (Wadi Kashtan), and shared fruitful religious discussions with pious locals. They crossed several valleys before reaching the salty waters of Mount Gharian, then moved toward Sondos, al-Shubaykah, Wadi Umm al-Ahwal, and finally the Sabkha region.

They entered Tozeur in Tunisia, which Ibn al-Tayyib called a “great city where a pilgrim finds all he needs.” He met jurists and engaged in deep theological debates, never neglecting to visit local shrines.

He then traveled through Kiriz to Gabès, where Tunisians welcomed him under the shade of palm trees. At Mart, he visited the tombs of Sidi Sālim Qabila and Sidi ʿAbd Allah al-Maghribi. The route continued through ʿArām, Wadi al-Samara, salt lakes, and the port of Djerba—where they paused until the group was complete—before heading to Bir al-Muwailiḥa.

Passing Ibn Mardan and the distinctive architecture of Zawagha, they reached Qarqarsh and finally Tripoli on the 25th of Shaʿban. He praised the city as more beautiful than Damascus and forged close friendships there.

On 4th Ramadan, he departed for the mountains of Barqa, stopping in Tajoura and other areas, marveling at the towering Mount Dazna and its Berber villages. Eventually, he reached Giza and visited the Pyramids, then spent the night joyfully in Kirdasa.

In Cairo

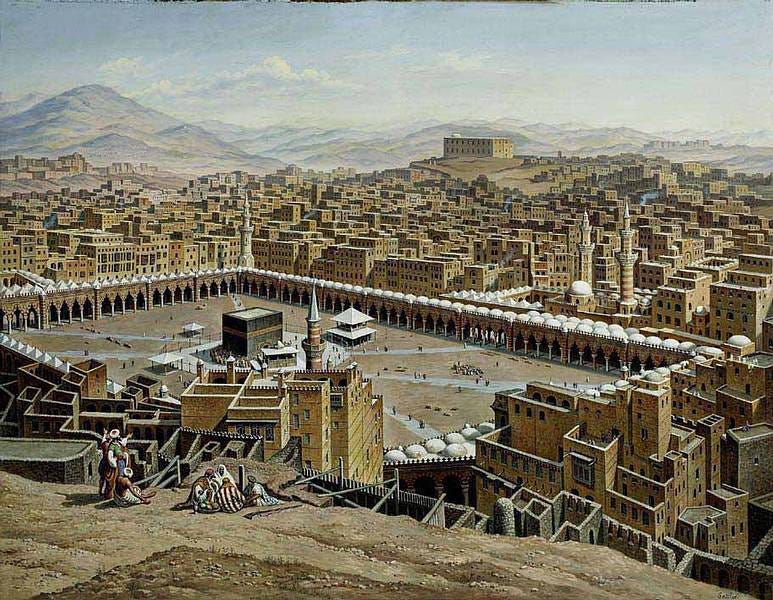

Ibn al-Tayyib explored Cairo’s streets, al-Azhar, the shrines of Ahl al-Bayt, the tomb of Imam al-Shafi‘i—whom he considered “the spiritual ruler of Egypt.” He also attended the majestic Kaaba covering ceremony, a major event drawing all segments of society, including Sufi orders, soldiers, and beggars alike.

Egyptian Pilgrimage Routes

Moroccan pilgrims typically chose either the land or sea route to the Hijaz. Ibn al-Tayyib opted for the land route. Just before departure, tragedy struck: his dear friend Abu ʿAbd Allah contracted the plague. Torn between continuing or staying, he chose to go—at his friend’s urging—but with a heavy heart.

In Mecca and Medina

He arrived in Mecca on 6 Dhu al-Hijjah, overwhelmed with emotion as he performed the arrival circumambulation, drank from Zamzam, and completed the saʿy between Safa and Marwa. He described the Kaaba with poetic fervor, portraying it as a luminous marvel.

He visited the Prophet’s birthplace, companions’ homes, and engaged in scholarly discussions, notably with Indian scholars. He admired Mecca’s lively markets—especially in Mina—and noted the popularity of its coffeehouses during Hajj.

On 24 Dhu al-Hijjah, he departed for Medina. At the sight of its domes, tears filled his eyes. He spent three days there, reciting poems in the Prophet’s Mosque, meeting dignitaries, visiting Baqi‘ cemetery, Quba Mosque, Mount Uhud, and the tomb of Hamza ibn ʿAbd al-Muttalib.

Despite longing for home, he found solace in shrine visits. His journey was marred by repeated thefts—first in Shu‘ayb, then in Mina, where his entire tent was looted, echoing the wider insecurity faced by pilgrims due to bandits and natural disasters.

Water scarcity loomed large, forcing pilgrims to meticulously plan around wells and springs. He also criticized the crowding between Safa and Marwa, the commercialization near the Grand Mosque, and exploitative practices like barbers only shaving half a head to serve more clients quickly.

He lamented hasty decisions by pilgrimage leaders to skip stops, exacerbating hardship under the blazing sun.

After the Hajj

Upon returning to Fez, Ibn al-Tayyib was met with famine and chaos, which led him to consider migration. The Ottoman authorities in the Hijaz, committed to supporting scholars and institutions, drew him back to the region.

He eventually settled in Medina, where he taught in the Prophet’s Mosque and performed a second Hajj. Though he never stopped longing for Fez, he remained in Medina until his death in 1170 AH / 1756 CE. He was buried near Lady Halima’s tomb.