It was my first year as a master's student at Birzeit University when our lecturer stood in the middle of the hall and asked, "Who among you is from the '48 territories?" Some of us raised our hands. He nodded, then asked the rest of us, "What terms are used in your family, city, or community to describe your colleagues from the '48 territories?" Our answers poured out, striking his bald head like a drum.

Some said, "Israeli Arabs," "Palestinian Arabs," "Palestinians of the interior," "Arabs of '48." The lecturer swallowed his disdain and asked again about the general characteristics we associate with them.

Our responses varied: their appearance, with headscarves revealing most of the hair or styled as turbans; their distinctive accent when saying "asa," akin to "hassa," "halkeit," "halla," meaning "now"; their consumer habits of buying without bargaining; their car license plates; and the Hebrew words that seep into their Arabic.

The lecturer paused, his bald head turning beet red, then unleashed his fury without raising his voice: "So, a word like 'asa,' a few extra shekels, and ten centimeters of headscarf have turned Palestinians like you into 'Israeli Arabs'?"

He suddenly turned to me and asked, "Do you recognize Israel?" I replied without hesitation, "Of course not." He then directed his anger at me: "Then how do you describe Palestinians like you, Arabs like you, some of them Muslims like you, as part of an entity you don't recognize?"

He asked my friend, "Are you Palestinian?" She affirmed, and he retorted, "Either you're not Palestinian when you call them 'Palestinian Arabs,' or Palestine, to you, is limited to what was occupied in 1948."

He addressed us all: "Why don't we call them our Arabs? Aren't they us? Why do we always label them with terms of differentiation and distance? As if we're superior because we fled and left our towns and villages, and they're the infiltrators who accepted the occupier's rule and nationality?

Has anyone ever thought they might be the brave ones and we the cowards? Have you considered that they alone are responsible for preserving what's left of 1948 Palestine, for Israel's failure today to declare itself a purely Jewish state?"

He added: "Has anyone ever asked what our steadfast Arabs were doing when we, the fearful majority, chose to flee and leave the country, accepting life under Jordanian and Egyptian umbrellas, under the mercy of UNRWA, Arab regimes, and the international community, while they were fighting the battle of survival, the battle of Arabism? Has anyone ever wondered if our Arabs shed blood for the land, while we sacrificed the land for honor and left with neither land nor honor?"

Since that day, the lecturer's questions have lingered, suspended between us and our colleagues (our Arabs in the lecture) and within ourselves. Over two years of study, the same lecturer began each new course with the same revolution, while I withdrew into a whirlwind of confusion, turning over thoughts:

"They are the ones who stayed, they paid the price, and we surrendered to fear. Why did we push them into the corner of marginalization as if they were the shadow and spearhead of the enemy?"

From this question and its dark reflections in the souls of Palestinians yesterday, today, and tomorrow, this piece attempts to shed light on those who clung on when everyone else let go, who lived their own exile alongside our greater exile, and who, when their chains loosened, approached us, only for us to distance ourselves and ostracize them, even though they are the remaining remnants of the homeland.

"I have chosen you, my homeland... let time deny me... as long as you remember me."

— Ali Youssef Ahmed Fouda

The Nakba did not begin precisely in May or even in 1948; it effectively started after the Great Palestinian Revolt in 1939, when the Zionist movement realized that the dream of a national homeland for Jews could not be fulfilled with an Arab majority.

They decided to use displacement as a punitive mechanism against Palestinian residents, leading to the expulsion of 40,000 Palestinians, before the United Nations accelerated the pace of displacement.

This occurred on November 29, 1947, when Resolution 181 was issued, dividing Arab Palestine into two states: a Jewish state covering 55% and an Arab state covering 45%. It unleashed Zionist gangs and their firepower on Palestinian villages and towns, turning scattered skirmishes and assaults into comprehensive attacks aimed at pushing Arab residents beyond the borders designated by the UN for the Jewish state.

In the initial months, the gangs' efforts to drive Arab residents away from the Jewish partition of Palestine were unsuccessful. As soon as the attacks subsided, Palestinians would sneak back into their areas or nearby. This continued until March 1948, when the gangs launched a unified displacement plan called "Plan Dalet," representing the peak of ethnic cleansing and displacement.

According to Plan Dalet, Zionist gangs aimed to attack from three directions, leaving one route open for Palestinians. The directions were coordinated geographically to converge on Palestinian towns, ending in a single line of unified displacement, forcibly pushing Palestinians out of the "Jewish state."

By April 9, 1948, the number of displaced Palestinians had reached 200,000, who had already crossed the partition borders. The attacks intensified, and their numbers rose after the gradual withdrawal of the British Mandate from key positions in the country.

Among them were thousands who preferred to hide among olive trees or returned repeatedly to the borders of their towns until the occupation realized that the country's existence incited its owners to return. So, they demolished homes and facilities, reducing them to ashes.

Writer Mohammad Kayyal recounts the story of his parents, who were displaced from al-Birwa after its occupation. The town's Muslim and Christian residents decided to return, gathered some weapons, repelled the Zionist gangs, and reclaimed it, holding onto their historical and international right based on the partition plan that included the town within the Arab state's borders.

Within a week, the Zionist gangs re-attacked and displaced the town's residents again. To ensure their displacement this time, they leveled the village's homes, mosque, and church, while most residents dispersed between the western Galilee, and refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, and northern West Bank.

His parents hid for days under olive trees before being pursued by Zionist gangs, forcing them to seek refuge in a neighboring village two kilometers from al-Birwa, hoping to return later.

A year after al-Birwa's displacement, the Israeli occupation government transformed it into an agricultural town, while the few who returned to its borders were expelled again under emergency laws and absentee property laws.

For the Kayyal family, the dream of return persisted until it was struck by the 1956 tripartite aggression, then fatally wounded by the 1967 setback. At that point, the family's dream shifted from returning to transforming the dilapidated hut sheltering them into a stone building sufficient to protect the family and provide permanent housing and stability.

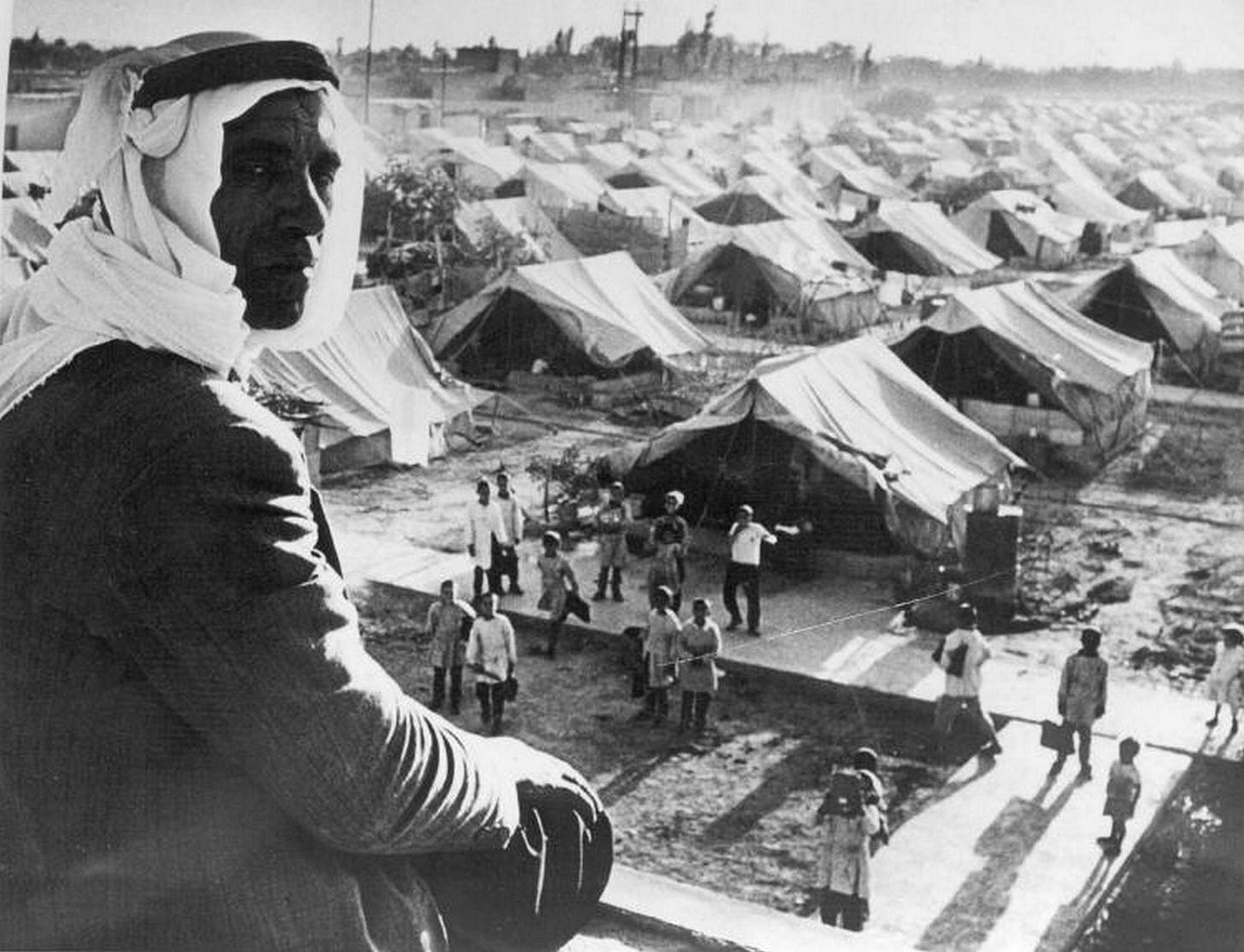

The Kayyal family's story mirrors that of 900,000 Palestinians uprooted from their towns, among whom 750,000 were displaced beyond the borders of fire and destruction sown by Zionist gangs, who declared their "state" on the ruins on May 15, 1948, while 150,000 managed to cling to the country's edges.

Among these 150,000, 25% were actually displaced from their original towns, but their tenacious clinging allowed them to stay within a stone's throw. To confront their rebellion and fierce determination, the occupation imposed a harsh military rule, turning their daily lives into a piece of torment.

"Inside me, a balcony no one passes by to greet."

— Mahmoud Darwish

During the years of military rule from 1948 to 1966, the Israeli government imposed a series of laws and military orders that deprived them of normal life, such as movement, work, and political activities.

It confined them to narrow geographic areas within major cities, while seizing the agricultural lands surrounding the displaced towns and villages, and implementing strict surveillance systems on Arabs, considering them internal enemies.

Among the laws enforced during that period was the British Emergency Law enacted in 1945 under the name "Defense Regulations," which Israel used to impose military rule, administrative detention, village and area closures, curfews, and property confiscation.

This enabled the military governor to control and manipulate Palestinian lives, arresting, exiling, or preventing them from entering their lands, or killing them for violating curfew.

Also, the 1948 Uncultivated Land Law granted the Minister of Agriculture the authority to take possession of land and exploit it for up to 35 months, and to confiscate it if proven used for non-agricultural purposes.

The 1949 Security Zones Law gave the Minister of Defense the authority to confiscate lands and displace residents in border areas under military and security pretexts.

Added to these was the Absentee Property Law enacted in 1950, allowing the occupation authorities to confiscate the properties of 80% of Palestinians, estimated at one million dunams of land, under the pretext of their absence, even if they moved to a neighboring area or couldn't return due to security closures or emergency regulations. The law restricted the transfer of properties to the Development Authority only.

In the same list of laws, the Development Authority Law, known as the Property Transfer Law of 1950, was temporally and politically linked to the Absentee Property Law. Based on it, the Development Authority was established to buy, lease, exchange, sell, and manage lands as an owner, provided they weren't sold to anyone other than the state or the Jewish National Fund.

There was also the 1950 Law of Return and the 1952 Citizenship Law, which allowed Jews worldwide to immigrate to Israel and obtain its citizenship upon entry, in contrast to the civil and legal humiliation faced by Palestinians, leaving them at the bottom of the citizenship acquisition ladder, excluding most for many years, and seizing their basic civil rights.

The 1953 Land Acquisition for Public Purposes Law gave the occupation authority the right to confiscate lands in Arab areas for road construction and facilities serving Jewish areas. Consequently, Arab towns lost their vital space, and their lands became public parks for Jewish towns.

The 1953 Acquisition, Validation, and Compensation Law legalized all post-Nakba confiscations, presenting Palestinians with only one option: accepting financial compensation for their properties offered by the Development Authority and the Israel Lands Administration, in exchange for legal relinquishment. It's important to note that the percentage of those who received compensation was very limited.

Beyond written laws, there were a series of oral and sudden military orders issued by the military governor, surprising Palestinian residents and disrupting their lives, such as travel and movement bans, separating villages with wires and barriers, sudden raids and searches, banning meetings, and preventing the appointment of teachers, imams, and employees without the governor's approval.