Iran's "Look East" policy reflects both its geopolitical realities and strategic ambition to align with the Eastern bloc comprising China, Russia, and Central Asian nations. It also directly challenges the United States by threatening its interests in the Middle East and contributing to a global shift toward a new bipolarity that undermines post-Cold War American dominance.

But what exactly is the "Look East" policy? How did it emerge, and what are its key drivers? And how has Washington interpreted this pivot? This article explores these questions and assesses the implications of Tehran's eastern orientation in the broader struggle for global influence.

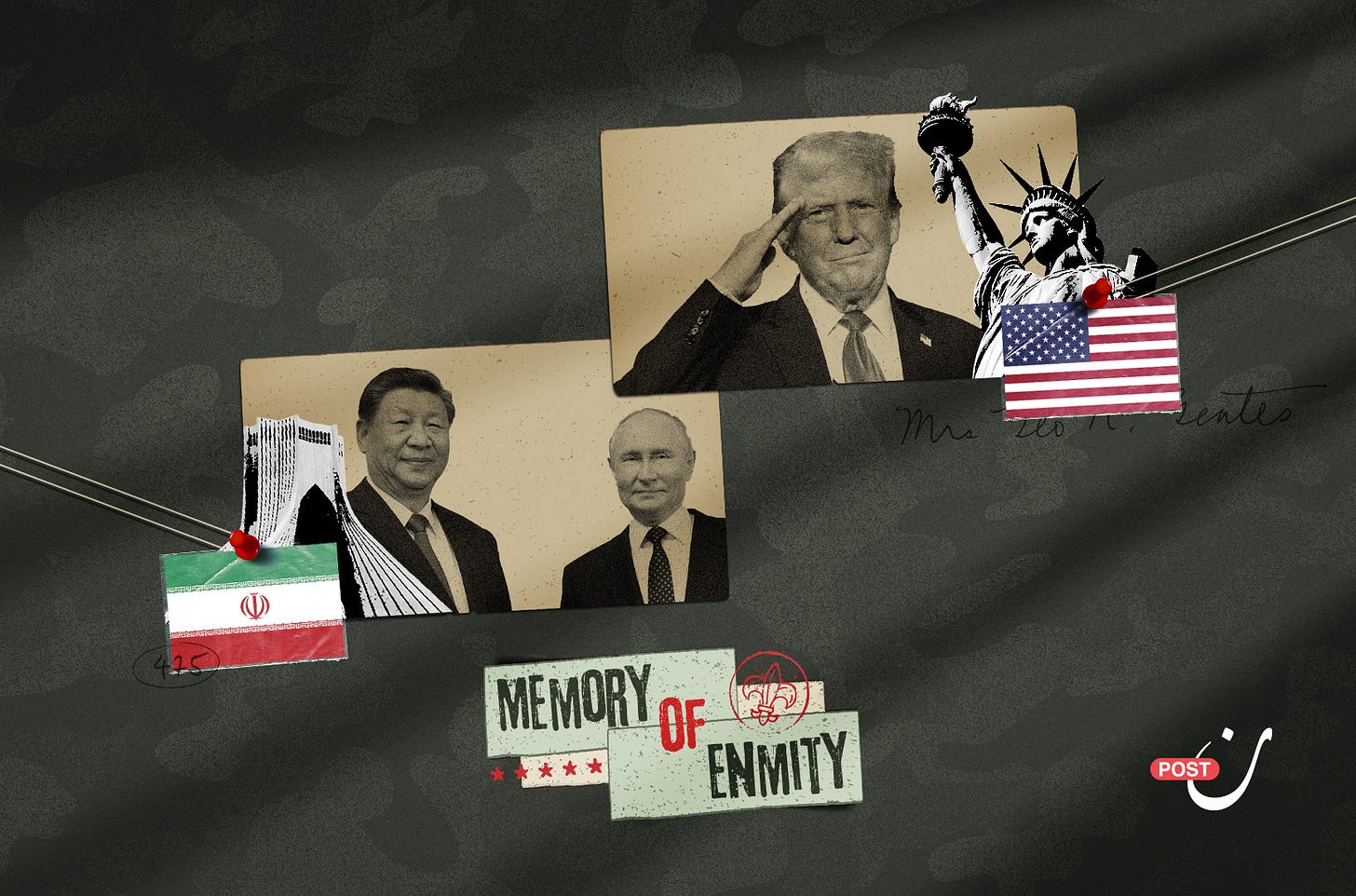

This analysis is part of the "Memory of Hostility" series, which traces the turbulent trajectory of US-Iran relations—how enmity became a cornerstone of American Middle East policy, justifying arms races, alliances, and sanctions. The series also attempts to forecast the future of this fraught relationship amid rapid regional and global transformations.

Survival Strategies

In the wake of Ayatollah Khomeini's revolution, Iran adopted the slogan "Neither East nor West," emphasizing national self-determination and distancing itself from the global powers. Yet, Tehran soon realized the challenge of navigating a polarized world alone.

"Looking East" broadly denotes a foreign policy strategy focused on strengthening economic, political, and strategic ties with Eastern powers—chiefly China and Russia—to reduce dependence on the US and Western institutions.

Iran developed this strategy along two intertwined paths: forging military and economic partnerships with America's adversaries while countering the crippling sanctions and isolation imposed by Washington. Even under hardline governments, Tehran has often extended overtures to the West, only to be rebuffed, further pushing it eastward.

The policy began to take form in the 1990s, as Iran emerged weakened from the Iran-Iraq War. Isolated in a Sunni Arab world aligned with Washington, Tehran sought economic alternatives and technological advancement. It viewed post-Soviet and East Asian states as a historic opportunity, aiming to transform Iran into an "Islamic Japan."

Yet initially, "Looking East" was more of a tentative tactic than a coherent foreign policy. Iran's ideological rigidity, rivalries with regional powers like Turkey and Saudi Arabia, and US influence in Asia hampered early efforts.

Despite past tensions with the Soviet Union, Khomeini expressed early interest in collaboration. In 1979, he indicated willingness to deepen political and economic ties based on mutual respect. During the Iran-Iraq War, the USSR supplied arms to both sides, but under Gorbachev's "New Thinking," Iran saw an opening for closer ties.

From Ahmadinejad to Raisi

The "Look East" policy gained traction under the presidencies of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013), Hassan Rouhani (2013–2021), and Ebrahim Raisi (2021–2024). Despite differing foreign policy approaches, all three administrations shared the goal of diversifying foreign relations to mitigate Western sanctions.

Ahmadinejad rose to power after reformist attempts at rapprochement with the West failed. Branded part of the "Axis of Evil" by President George W. Bush and pressured over Iran's nuclear program, Ahmadinejad sought lifelines in China and Russia, while also courting Latin America's leftist leaders, such as Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales.

However, his efforts failed to yield a robust Eastern alliance. Eastern states remained wary of Iran's identity and ambitions. Membership in organizations like the ECO and OIC often hindered rather than helped, given their members' Western ties.

Rouhani pursued a balanced policy, culminating in the 2015 nuclear deal and sanctions relief, while also deepening ties with Beijing and Moscow. Iran joined the AIIB, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Eurasian Economic Union during his tenure. Yet Trump's 2018 withdrawal from the nuclear deal and renewed sanctions pushed Iran further east, as encapsulated by Foreign Minister Javad Zarif's Asian Cooperation Doctrine.

Rouhani also expanded relations with India, signing a trilateral agreement with Prime Minister Modi and Afghan President Ghani in 2021 to link India to Central Asia via Iran.

Raisi's presidency marked a return to confrontation with the West and full embrace of Eastern partnerships. Under his leadership, Iran achieved full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and sought deeper ties with Russia, India, and Southeast Asia, while also improving relations with Saudi Arabia and Gulf neighbors.

The Russian Bear: A Risky Friendship

Though Tehran's Eastern ambitions extend beyond Moscow and Beijing, the two powers dominate Iran's strategy to counterbalance US pressure.

While China and Russia share an interest in opposing US hegemony, their dynamics with Iran differ. Russia's strategic cooperation with Tehran expanded significantly from 2005, with the rise of the IRGC and Ahmadinejad.

Nonetheless, Moscow has often disappointed Tehran. It delayed delivery of the S-300 missile system under Western pressure and restricted nuclear collaboration to civilian projects. Russia even supported UN sanctions from 2006 to 2010.

Ties intensified after the 2022 Ukraine war, with Iran supplying Russia with hundreds of combat drones. In return, Tehran received advanced military hardware. Recent agreements include strategic cooperation in defense, nuclear energy, and trade, with an aim to boost bilateral trade to $12 billion.

Yet economic ties remain lopsided. Russia's exports to Iran dwarf its imports. Moscow has declined to open its markets to Iranian goods and avoided energy sector cooperation due to competition in global oil markets. Promises to develop the North-South Transport Corridor remain mostly aspirational.

China: Cautious Partner

Beijing is Iran's largest trading partner and top oil customer. Despite participating in UN sanctions between 2006 and 2010, China resumed oil imports and signed backdoor deals to skirt sanctions.

Chinese oil imports from Iran grew steadily, reaching 1.4 million barrels per day in 2024. Still, Chinese investment dropped from $52 billion in 2014 to $15 billion in 2022 due to US pressure.

In 2021, China and Iran signed a 25-year cooperation plan promising $400 billion in investments, though implementation has been minimal. Military ties remain limited, with naval drills and technology transfers focused on internal security.

Trade with China remains modest: $15.8 billion in 2022 compared to $87.3 billion with Saudi Arabia. China has shown reluctance to jeopardize relations with Gulf states or the US over Tehran.

Disillusionment and Strategic Limitations

Despite symbolic gestures, Beijing and Moscow have consistently prioritized their own interests. They voted for UN sanctions in the past, dragged their feet on military deals, and refused to risk ties with Washington or regional partners.

Russia's coordination with Israel in Syria and hesitance to deliver arms frustrated Tehran. Similarly, China's neutrality and economic caution have exposed the limits of this Eastern alignment.

The three capitals share anti-Western rhetoric but lack ideological unity or mutual commitment. Their coordination often serves as leverage in unrelated disputes, like Ukraine or Taiwan.

Is Washington Concerned?

The US views Iran's Eastern turn as part of its broader challenge to the post-Cold War order. While Tehran's moves may be symbolic, they reflect a defiant posture that undermines US influence.

Washington has countered with sanctions targeting Iranian and third-party firms and strengthened Gulf alliances to block Tehran's financing routes. Despite limited integration, Iran's partnerships with Moscow and Beijing remain a strategic concern, particularly as proxies continue to destabilize the region.

Still, neither Moscow nor Beijing appear willing to fully back Iran. They continue to engage the West and avoid irreversibly aligning with Tehran. For now, Iran remains a useful card in their geopolitical games—but not a partner worth endangering broader interests for.