Sitting in front of your television, watching a blockbuster starring a famous American actor that grossed over $200 million at the box office, a jarring scene appears: frightened Americans in a car surrounded by throngs of "savages" screaming, tearing their clothes, and trying to drag them from their seats.

The scene, we learn, is set in Tehran—depicting Iranians bent on exacting revenge on helpless Americans.

Switch to the news: ominous music blares from a mainstream outlet, a large image of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei saluting followers with an outstretched arm uncannily reminiscent of a Hitler salute. You turn off the TV and pick up the day's paper.

Splashed across the front page are commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in military garb and long beards, standing before a world map—suggesting a looming, sinister plot.

This relentless fear campaign—crafted by successive U.S. administrations and bolstered by media outlets and societal institutions—has portrayed Iran and its people in a demonized light for over four and a half decades. Like a spiderweb, this campaign has been slow, deliberate, calculated, and deeply embedded in the American psyche, making Iran the default enemy.

Where does this anti-Iran narrative come from? Who fuels it? What justifies it? What are its regional consequences? And can it withstand a rapidly changing world? This article, part of the "Memory of Hostility" series, seeks to address these and other questions.

The Formation of Iranophobia in America

The anti-Iran discourse, commonly labeled "Iranophobia," is a complex narrative rooted in prejudice, racial bias, preconceived notions, and a media-driven agenda. It has cultivated an exaggerated and unfounded fear of Iran's regional power, its potential acquisition of nuclear weapons, and the perceived existential threat that poses to Western civilization and domestic security.

This discourse is neither uniform nor monolithic; its motivations and intensity vary depending on the political and cultural context. It often intersects with other American forms of xenophobia and Islamophobia.

While Iranophobia and Islamophobia share ideological and racial underpinnings—both framing Muslims and Iranians as ideological threats—their historical trajectories, the tools employed to perpetuate them, and their domestic and international implications differ.

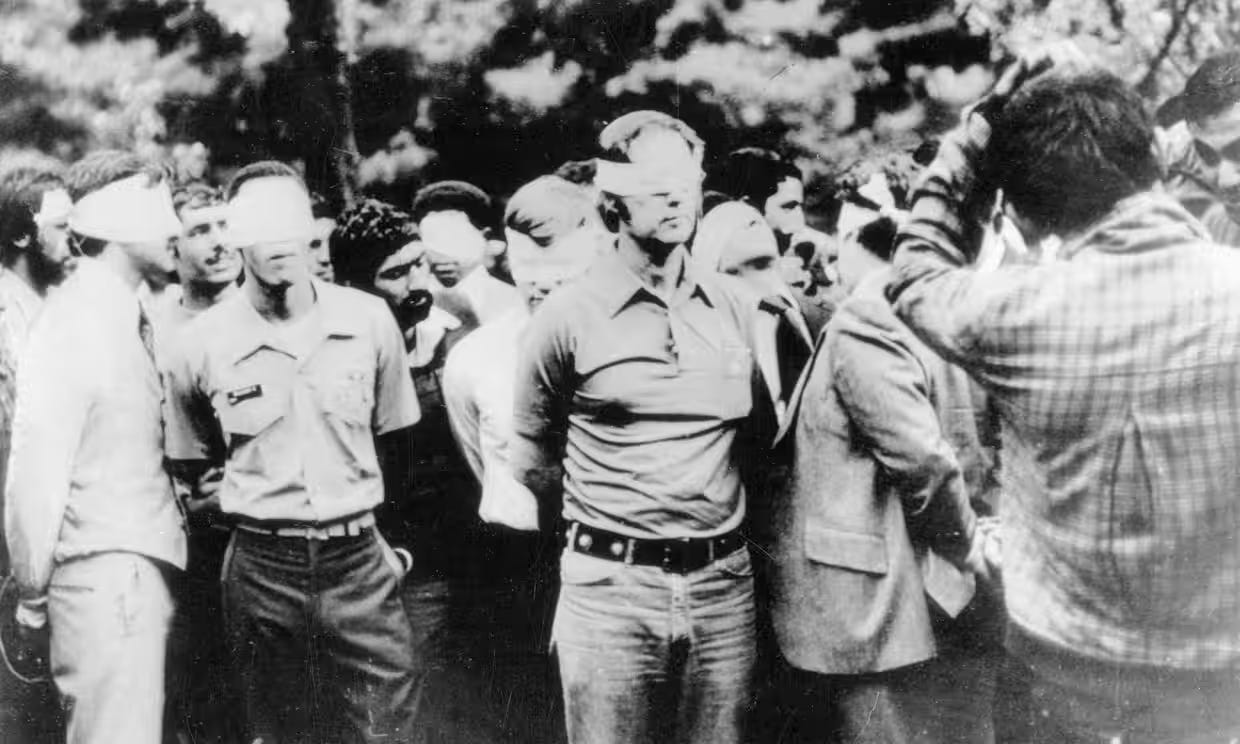

The term "Iranophobia" first emerged during World War II but gained real traction in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the Shah, once a staunch U.S. ally, was overthrown and replaced by a regime hostile to the West. The 444-day hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy in Tehran marked a dramatic turning point, solidifying fear as a political tool.

The U.S. has long employed the "external enemy" theory—positioning certain countries as existential threats to justify domestic mobilization and foreign interventions. Iran fit this model perfectly, especially during the Cold War, when fears of it aligning with the Soviet Union led to Washington's orchestration of the 1953 coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and the reinstatement of the Shah.

Iranophobia serves a dual function. Domestically, it justifies American foreign policy. Regionally, it benefits U.S. allies—especially Israel—by framing Iran as a perpetual existential threat. This shared enemy narrative strengthens alliances and allows for global policy maneuvers beneficial to both Washington and Tel Aviv.

Israeli scholar Haggai Ram traces Iranophobia back to the cultural clash between secular Ashkenazi Jews and religious Mizrahim. In his book Iranophobia: The Logic of an Israeli Obsession, Ram argues that the Iranian revolution, with its traditionalist values, posed a symbolic threat to Israeli modernity.

Conversely, journalist Ira Shirnas, in his piece Monsters to Be Destroyed, sees Iranophobia as driven less by ideology and more by control over oil and military dominance. For Shirnas, the hostility stems from geopolitical rivalry, though he acknowledges the media’s critical role in shaping public sentiment through fear-based narratives.

Interestingly, Iran’s regime has also exploited this adversarial image to consolidate power internally, conflating anti-Iranian rhetoric with Islamophobia to rally nationalist sentiment and present itself as a sovereign Islamic counterweight to Western imperialism.

Hate-Making on the Big Screen

American media has for decades portrayed Iran as regressive, oppressive, and hostile—a rogue state threatening both regional and global stability. Drawing on Orientalist tropes, U.S. media often ignores Iran’s rich history and culture, reducing it to a caricature of fanaticism and terror.

The 1979 hostage crisis triggered this wave of demonization, humanizing the hostages and dehumanizing their captors. Khamenei was cast as the face of radical Islam, and the conflict was framed as a civilizational clash: Islam versus Western liberalism.

Over time, this narrative stuck. From President George W. Bush’s “Axis of Evil” designation to repeated media portrayals of Iran as inherently violent, the image of an irredeemable, war-mongering nation took root in the American imagination.

Despite brief diplomatic overtures, such as the 2015 nuclear deal, major outlets like CNN and Fox News consistently framed Iran as duplicitous and dangerous—an actor to be constrained, not engaged.

Hollywood has played a central role in this perception war. From Argo (2012) to Syriana (2005), and series like Homeland and Tehran, Iran is consistently depicted as a dystopia filled with nuclear scientists, spies, and oppressed women. Even historical epics like 300 cast ancient Persians as savages. These portrayals reinforce fear and prejudice in subtle yet powerful ways.

The Invisible Hand of the Pro-Israel Lobby

Pro-Israel lobbying groups, particularly AIPAC, have significantly influenced U.S. policy toward Iran—lobbying for sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and even military action. Their media influence, campaign financing, and think tank alliances have fueled bipartisan hostility against Tehran.

AIPAC alone spent over $100 million during the last election cycle to support hardline candidates. Trump’s administration was heavily staffed with anti-Iran hawks like Mike Pompeo and Mike Pence, who orchestrated the assassination of Qassem Soleimani. Pressure campaigns also targeted public opinion, painting Iran as the new Nazi threat.

These groups also pushed aggressive messaging campaigns in public transport systems, universities, and think tanks—many aligned with the Netanyahu government—to cement Iran as a global menace.

The Arab Front and Shifting Sands

Interestingly, the most consequential moment in the evolution of Iranophobia didn’t occur in Tehran but in Cairo. The Egypt-Israel peace agreements reframed Iran as the region’s primary menace, nudging Sunni Arab regimes fearful of Islamist uprisings closer to Israel and the U.S.

Despite their pre-revolution ties with Iran, countries like Egypt actively supported counter-revolutionary efforts, including offers to assist exiled opposition groups. The fear of Iranian ideological expansion fueled normalization with Israel and deepened Sunni-Shia rifts.

This fear-based alignment peaked during Iran’s involvement in Syria alongside Bashar al-Assad, stoking Arab hostility. Yet Iranophobia is not the sole driver of normalization; changing global dynamics, like China’s rise and shifting regional priorities, have altered the equation.

During Biden’s presidency, cracks appeared in the Abraham Accords. Promises made to Gulf states by the Trump administration went unfulfilled. Israel’s failure to protect its new allies post-October 7 further disillusioned them.

As Gulf nations hesitate to back U.S.-Israel war efforts against Tehran, fearing retaliation and doubting Western protection, Iranophobia as a unifying doctrine may be losing its hold—making room for recalibrated alliances based on mutual interests rather than manufactured fear.