In an unprecedented escalation across several parts of Syria in recent days, the Islamic State (ISIS) has claimed a series of attacks targeting Syrian government forces, declaring the beginning of its war against the new Syrian state. This surge in violence marks a dramatic return after nearly a year of dormancy.

Since the launch of Operation “Deterring Aggression” and the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, ISIS’s media outlets have consistently vilified the former revolutionary factions and, later, the new Syrian state inciting against it relentlessly. Yet, until recently, the group had not directly targeted the new government’s forces.

The turning point came on December 1, when ISIS operatives assassinated a Syrian soldier and wounded another in an attack on the town of Saraqib in Idlib province. The group formally claimed responsibility, describing it as the first direct assault on what it called the “apostate Syrian regime.”

The Saraqib attack marked the beginning of a wave of operations against Syrian security forces, which intensified in the first half of December. In total, six attacks were carried out across Idlib, Aleppo, Damascus countryside, and Deir Ezzor—marking the most significant escalation since the new state’s formation.

These followed three earlier attacks in late November in Deir Ezzor, Homs, and Hama, which primarily targeted former regime loyalists and members of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Joining the International Coalition: A Spark for War

After the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in a twelve-day campaign by the “Deterring Aggression” forces, ISIS abruptly halted its operations in Syria. The group officially dissolved its so-called “security province” in the Syrian desert where it had fought the former regime from 2019 to 2024 and its Syrian fighters returned to their home regions, while many foreign militants, primarily Iraqis and Lebanese, fled through smuggling routes.

For almost an entire year, ISIS refrained from firing a single shot at the forces of the new Syrian state, even as its official newspaper Al-Naba and affiliated propaganda channels escalated their verbal assaults on President Ahmad al-Shara‘ and his government—branding them as apostates, traitors, and agents of Turkey and the West.

Two primary factors appear to have informed ISIS’s temporary pause:

Strategic Preparation: ISIS was regrouping and preparing for its next phase of operations. Since the beginning of 2025, the group had resumed recruitment drives, stockpiled weapons, and reactivated sleeper cells throughout Syria.

Building a Justification: The group sought a strong pretext to launch its new campaign particularly to justify its actions to the Sunni population, many of whom are staunch supporters of the new regime. Although ideology typically overrides such considerations for ISIS, in this case, it saw value in cultivating a veneer of legitimacy.

That justification came in November, when Syria officially joined the US-led Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. The U.S. Embassy in Damascus announced the move in a post on X (formerly Twitter), calling it “a pivotal moment in Syria’s history and in the global war on terror,” adding that Syria had become the coalition’s 90th member.

On November 30, the Coalition announced its first joint operation with Syria. According to U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), the operation, conducted with Syria’s Interior Ministry between November 24 and 27, targeted and destroyed more than 15 ISIS weapons caches in southern Syria.

Immediately following that announcement, ISIS launched a series of attacks on Syrian forces. Between November 28 and December 16, the group claimed eight attacks, culminating in the bombing of a Syrian military vehicle in Al-Bukamal, eastern Deir Ezzor.

Propaganda: ISIS’s Most Potent Weapon

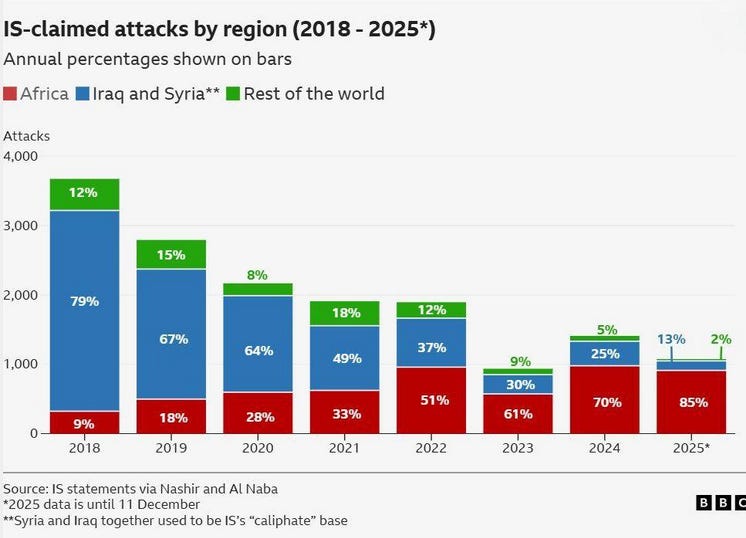

Despite its reemergence in regime-controlled areas and sporadic activity against the SDF in northeastern Syria, ISIS remains relatively weak in its historical strongholds of Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In fact, 2025 has recorded the group’s lowest operational activity in Syria and Iraq to date, accounting for just 13% of its global operations. Its power center is now increasingly shifting toward Sub-Saharan Africa.

Nonetheless, ISIS continues to wage an aggressive propaganda campaign in Syria, targeting the new state through Al-Naba and a network of unofficial “supporter accounts” across social media. These outlets encourage attacks on Syrian forces under the slogan, “Wherever you find them.” This rhetoric is already having real-world consequences as seen in the recent attack in Palmyra.

The Palmyra Attack: Motives and Consequences

On Saturday, December 13, in the first incident of its kind in central Syria, joint Syrian-American forces were ambushed in Palmyra. The attack resulted in the deaths of two soldiers and an American interpreter, injuries to three other U.S. personnel, and the wounding of two Syrian security officers.

The assailant struck near Branch 221 of the Badiya Directorate and, according to Syrian Interior Ministry spokesperson Nour al-Din al-Baba, held “extremist, takfiri beliefs.” He had been enlisted in Syrian security forces and was already undergoing dismissal procedures.

Although ISIS did not claim responsibility in its latest issue of Al-Naba (#526), it praised the attack as a product of its incitement. Observers suggest this may indeed be the case, as the attacker appears to have been influenced by ISIS’s ideological messaging.

The timing of the Palmyra attack was especially sensitive. The Syrian government has been actively working to build trust with the international coalition and position itself as a credible alternative to the SDF in the fight against terrorism.

Compounding the blow, the attack occurred just as the U.S. Caesar Act sanctions were lifted undermining Damascus’s efforts to forge stronger security and military alliances.

Following the attack, President Donald Trump vowed retaliation but refrained from blaming the Syrian government. On the night of December 19, the U.S. carried out a wave of airstrikes in the Syrian desert. The New York Times quoted a U.S. official as saying the military struck dozens of ISIS targets, including weapons depots and operational support structures.

The U.S. Secretary of Defense also announced the launch of Operation “Hawk’s Eye” to dismantle ISIS infrastructure in Syria. He emphasized that the strikes were retaliatory rather than the start of a new war.

Yet, these airstrikes may have been more symbolic than substantive. ISIS has largely relocated from the deserts to populated areas in the heart of Syria, no longer needing to hide in remote terrain as it did under the former regime.

On the domestic front, Syrian security forces carried out three counterterrorism operations following the Palmyra attack, targeting ISIS cells in Palmyra, Damascus countryside, and Idlib, according to official media.

The coalition, working with Syrian forces, also conducted joint raids in eastern Raqqa on December 18 in the town of Ma’dan, followed by another operation with Iraqi forces in Rabia, eastern Hasakah, resulting in the arrest of three individuals.

CNN reported that U.S. forces and their partners conducted ten operations since the Palmyra incident, killing or capturing around 23 suspected militants.

According to sources who spoke to Noon Post, the international coalition has also launched a comprehensive review of SDF prisons, including recent releases—suggesting growing concerns that former ISIS members may be entering government-held areas after their release.

The ISIS Threat: Realities and Remedies

The Palmyra attack laid bare critical weaknesses in the security structure of Syria’s nascent state. It highlighted the system’s vulnerability to infiltration by remnants of the Assad regime and individuals radicalized by ISIS ideology bringing the issue of military recruitment back into sharp focus as a matter of national security.

After the regime’s fall and institutional collapse, the new authorities faced a vast security vacuum amid simultaneous conflicts in the coastal regions, Suwayda, and the northeast. Under pressure to fill the ranks quickly, security institutions relaxed their vetting standards admitting recruits with questionable backgrounds.

The problem was compounded by short, inadequate training courses and widespread favoritism, particularly through tribal and familial networks. These factors allowed hundreds of individuals with criminal or extremist ties to infiltrate the army and security forces.

Despite rising public anger and limited purges targeting figures linked to former pro-Assad militias and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard in Deir Ezzor, experience has shown that true stability requires a complete overhaul of the recruitment process laying the foundation for a professional security apparatus capable of confronting ISIS and other existential threats facing Syria’s emerging state.