“Israel’s Moment of Reckoning Will Come from Within Israeli Society and the Jewish Community” - An Interview with Daniel Zoughbie

Read the interview in Arabic

Since the arrival of the first American ships on the shores of the Levant in the 19th century bringing with them missionaries and Protestant schools in Beirut, Sidon, and Jaffa, eventually reaching Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Damascus Arab-American relations were never primarily driven by mutual interests. Rather, they were shaped by the curiosity of an emerging power.

At the time, the United States had not yet become a global force, and the Arab world, while central to European competition, had not yet become the focal point of international conflict. Still, that foundational moment planted the seeds of a long and evolving entanglement that would intensify and take on new forms every decade.

With the two world wars, Washington began to view the Middle East as a geographic and political bridge connecting three continents. Then, in the mid-20th century, oil emerged as the pivotal factor that transformed the nature of the relationship from one rooted in culture and human engagement to a strategic alliance centered on energy, security, and military coalitions.

After 1945, the U.S. became the true inheritor of British influence in the region, propping up regimes, toppling others, and redrawing maps through the lens of Cold War anxieties.

The pace of transformation accelerated: the 1953 coup in Iran (which the CIA admitted in 2013 to having orchestrated against the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh), the 1956 Suez Crisis, and the 1967 Six-Day War that pushed Washington to fully embrace Israel as a core ally.

The 1973 oil shock gave Arab states, for the first time, real leverage over the United States, forcing Washington to rethink its approach. The Camp David Accords then established Egyptian-Israeli peace as the cornerstone of U.S. Middle East policy from Carter through Clinton.

By the turn of the century, three axioms had crystallized in the American mindset: the security of Israel, the stability of allied regimes, and the fight against “terrorism.” The 9/11 attacks marked a major turning point, prompting the U.S. to invade two Muslim-majority countries—Afghanistan and Iraq—and to reengineer the region through military force rather than political strategy.

Then came the Arab Spring, which exposed the fragility of this American understanding of the Middle East, revealing a Washington that was hesitant, confused, and unable to predict the nature of the transformation unfolding before its eyes.

Today, amid the spectacular fall of the Assad regime and the rise of new leadership in Damascus, shifting energy dynamics, and the growing influence of China and Russia alongside new regional players like Turkey, India, and Iran the question of whether Washington truly understands the Middle East? is more urgent than ever.

To explore this question, we spoke with Daniel Zoughbie, an American scholar of foreign policy and Middle Eastern diplomacy.

Who is Daniel Zoughbie?

Daniel Zoughbie is an American complex systems scientist and historian specializing in U.S. foreign policy, development, and Middle East diplomacy. His published research focuses on presidential decision-making and its impact on regional conflicts, particularly the Israeli-Palestinian dispute.

He holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of Oxford and currently leads a research initiative on development, diplomacy, and defense in the MENA region at the University of California, Berkeley.

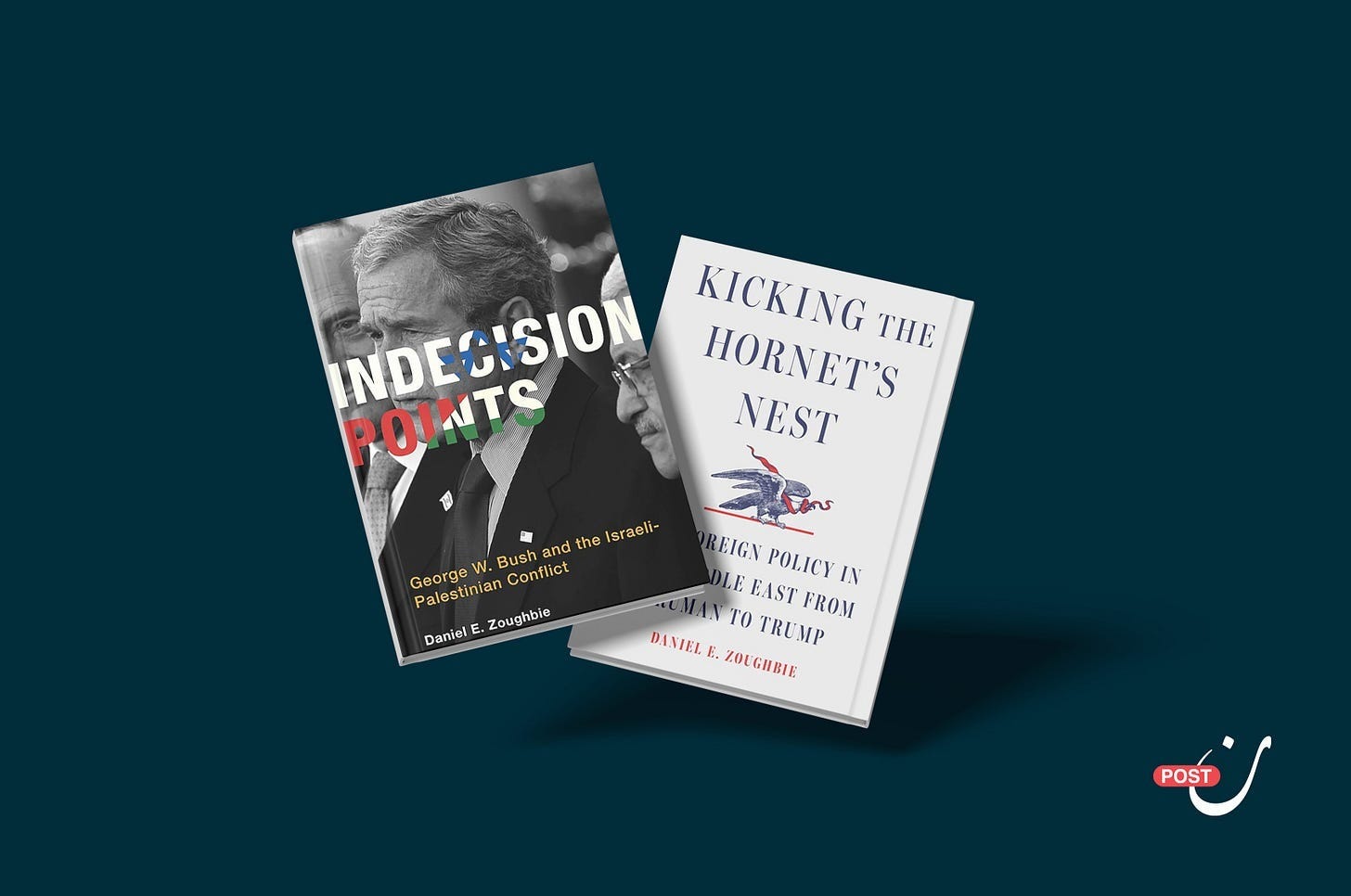

Zoughbie previously held positions at Harvard, Stanford, Georgetown, and other universities. He has published in leading public health journals and is also the author of two books on the topic of international security:

Indecision Points: George W. Bush and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (2014)

Kicking the Hornet’s Nest: U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East from Truman to Trump (2025)

In this in-depth conversation, we delve into Zoughbie’s analysis of 80 years of American engagement in the Middle East, unpack insights from his books, and reflect on the hesitant, often contradictory nature of U.S.-Arab relations.

Read on for the full interview…

— U.S. envoy to Syria Tom Barrack appeared “utterly confused” and unable to decipher the “real mystery” of why regional powers like Egypt and Saudi Arabia won’t accept Palestinian refugees being driven from their land by Israel as if the ethnic cleansing of a people were a given.

Based on your study of 80 years of American foreign policy and the actions of successive U.S. administrations…

Does Washington truly understand the social and political dynamics of the Middle East?

DZ: It’s relative.

I believe many American policymakers over the past eight decades have demonstrated a deep understanding of Middle Eastern cultural, societal, and economic dynamics, or at the very least, offered highly sophisticated insights into human nature and the international system.

People like President Gerald Ford (1974–1977), General George C. Marshall (Secretary of State and Defense, Nobel Peace Prize winner), and Ambassador George Kennan (the architect of Containment policy) recognized the stakes. But often, they weren’t listened to. And today, similarly capable experts are being sidelined in much the same way.

Nationalism is a central driver of conflict. It’s the idea that the nation-state, whether secular or religious, matters more than anything else. Over 120 million people died in the last century because of nationalism.

It’s an incredibly powerful force in international politics. That’s why the best hope for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian-Arab conflict is to find ways of satisfying both sides’ nationalist aspirations.

As I explain in Kicking the Hornet’s Nest, Gerald Ford (with the support of Henry Kissinger) took the right approach. He pressured the Israelis to negotiate seriously with the Egyptians, even threatening to reassess the U.S.-Israel relationship.

Ultimately, this led to the “land for peace” formula. That peace remains the cornerstone of both U.S. and Israeli security in the region. Ford stood up to a close ally, faced heavy backlash, and did the right thing.

The same principle should be applied today.

— After examining the policies of 13 U.S. presidents...

Why do certain constants like unwavering support for Israel and the fight against terrorism seem immune to change in American administrations?

DZ: American security is built on three pillars: defense, diplomacy, and development. But policymakers have severely weakened diplomacy and development, focusing almost entirely on defense spending–both covert and overt military operations. That’s been unfortunate for the U.S. and for its allies, including those in the Arab and Muslim worlds.

It’s much easier to lean on the simplistic belief that “might makes right,” while engaging in the hard work of reconciliation through diplomacy and development is far more difficult.

I often refer to General George C. Marshall, whose post-WWII plan rebuilt Europe. He understood you can’t live by the sword forever. In fact, he extended massive aid to former enemies because he didn’t want a repeat of the post-WWI punitive approach that sowed the seeds of more war.

One of my book’s central conclusions is just how self-defeating it is to “live by the sword.” Is the U.S. more secure today? Is Israel? Is Iran? Is Turkey? Is the Arab world? Is humanity?

Despite massive defense spending, the U.S. now faces unprecedented security challenges. The nuclear standoff involving Israel and Iran could easily drag Russia or even China into a Middle East war with global consequences.

The question of why the U.S. supports Israeli interests is a fascinating one. When I’m asked this—as I often am—I pose what I think is a more critical question: Why does the U.S. support pro-Israel policies that serve neither U.S. nor Israeli interests?

A two-state solution based on 1967 borders is in America’s interest. It’s in Israel’s interest. It’s in Palestine’s interest. It’s in the Arab world’s interest.

Decades ago, George Ball, a senior State Department official, wrote a piece titled “How to Save Israel in Spite of Herself.” That was his view as well.

And I return here to my core thesis: the U.S. has allowed its diplomatic and development capacities to atrophy, relying too heavily on defense spending—wars, coups, and arms deals.

As for terrorism, American foreign policy has often exacerbated the problem with its ill conceived interventions. Why did al-Qaeda emerge? What about ISIS?

— Is what we’re seeing now in Syria a shift in institutional U.S. policy, or just a temporary exception tied to Trump’s personal views and deal-making?

How do you interpret Donald Trump’s openness toward the new leadership in Syria?

DZ: That’s a tough question to answer for two reasons:

First, Trump’s decision-making process is notoriously opaque. There’s little evidence of methodical policy planning. He governs by instinct.

Second, the meteoric rise of Syria’s new president—once a senior ISIS figure and a former U.S. detainee in Iraq—is extraordinarily unusual. There are clear ties to Turkish intelligence, which is part of NATO. That’s a backstory worthy of its own book.

In the U.S., there appears to be a general openness toward the new government in Damascus. This new president is embarking on a global tour to reintroduce himself—meeting with former CIA Director David Petraeus, giving interviews, and so on.

But the real questions are: how long can he stay in power, given Syria’s deep sectarian divides?

And even if he does, will Syria truly be better off than it was before Assad was ousted?

— Promoting democracy has long been a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy. Yet Washington didn’t seem particularly enthusiastic about the Arab Spring save perhaps in Libya. Elsewhere, it appeared hesitant and disoriented, and in Egypt, it seemed comfortable with the military coup that toppled the country’s first elected government.

How do you interpret the U.S. stance toward the Arab Spring?

DZ: The very idea of “exporting American democracy” to the Middle East is fundamentally flawed especially when it arrives at the tip of a spear or under occupation. As I argue in both Indecision Points and Kicking the Hornet’s Nest, no great power should assume that its system of governance is the inevitable destiny of all humankind.

I live in the United States, and I appreciate its political system flaws and all. But democracy must be defended and nurtured. We should recall the wisdom of John Quincy Adams (US President, 1825–1829), who warned that America should not “go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

He understood that foreign adventurism would ultimately harm American democracy itself. The Iraq War is a case in point.

— In Indecision Points, you analyze George W. Bush’s indecision on the Palestinian issue. In Kicking the Hornet’s Nest, you cover Barack Obama’s hesitations on Syria.

How similar or different were their indecisions in terms of causes, conditions, and consequences?

DZ: That’s a valid comparison, and yes, there are parallels. Under Bush, the neoconservative coalition pushed for military intervention, particularly in Iraq and Palestine. Under Obama, liberal interventionists also pushed for military action especially in Libya.

But in some ways, Bush’s indecision on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was quite different from Obama’s muddled approach to the Arab uprisings. Bush oscillated between two mutually exclusive strategies: “parallelism” and “sequencing.” That’s what my first book, Indecision Points, is about.

“Parallelism” meant mutual Israeli-Palestinian concessions leading to negotiations and peace. “Sequencing” meant Palestinians had to first carry out internal reforms removing despots and terrorists before peace talks could begin. Bush kept swinging between these two poles and couldn’t commit.

Obama’s policy confusion stemmed from different factors. As I argue in Kicking the Hornet’s Nest, he was drawn into regime change in Libya a disastrous precedent for any nation considering nuclear disarmament. The lesson to countries like North Korea and Iran? Don’t give up your nukes or you’ll end up like Gaddafi.

In Egypt, we must recognize that there were multiple coups post-WWII: Nasser against King Farouk; Morsi against Mubarak (backed by massive protests); Morsi against the constitution (a soft coup); and finally Sisi against Morsi again with popular support. I examine all of this in my book.

In Syria, Russia intervened to block regime change, and the U.S. backed away from full-scale overthrow. But Washington continued covert operations, which ultimately led to a former ISIS commander taking power years later. That CIA program was called “Timber Sycamore,” and I detail it in the book.

As I said earlier, the big question is: where do things go from here? One hopes Syria stabilizes and avoids plunging deeper into sectarian strife.

— As the U.S. becomes more energy self-sufficient…

Has the Middle East lost its traditional strategic weight in Washington’s eyes, as envoy Tom Barrack suggested? Or is the energy battle now about control over distribution networks, not just production?

DZ: I don’t think the region has lost its strategic relevance.

The Middle East sits at the crossroads of three major continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe. It contains vital waterways through which much of the world’s oil and trade flows.

When the Suez Canal was briefly blocked by a shipping accident, the billions were lost. Nearly half of China’s oil imports pass through the Strait of Hormuz. Beijing won’t stand idly by if that flow is disrupted.

Add to that the religious significance: over four billion Jews, Christians, and Muslims consider parts of the Middle East sacred.

And now, the region is becoming a hub for mega energy facilities and data centers needed to power the AI revolution.

Most critically, Israel holds roughly 200-300 nuclear weapons. Iran is a nuclear-threshold state. Saudi Arabia, through its defense pact with Pakistan, has a “nuke-on-demand” capability. If non-proliferation efforts fail and NATO weakens, Turkey might pursue nuclear arms as well.

This is not a region any superpower can afford to ignore.

To what extent do U.S. policies—intentionally or not—complicate internal conflicts in the Arab world? And how do successive administrations justify their ongoing partnerships with authoritarian regimes in the region?

DZ: Every major or regional power seeks to expand its influence. So responsibility for today’s crises in the region must be shared.

That said, my book focuses on American foreign policy, not on China’s or Russia’s. And the evidence clearly shows how short-sighted U.S. strategy has often been. Take its non-proliferation policy in the Middle East and South Asia; it has brought us to the brink of a very dangerous security competition.

The democracy-versus-authoritarianism debate is also critical.

I live in the U.S., and I prefer life in a democracy. But I also understand that the U.S. cannot impose its lifestyle on others—at least not without incurring massive costs. Nor can it isolate itself and engage only with fellow democracies.

That means dealing with non-democratic regimes and respecting other cultures and ways of life. But that doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to human rights abuses—especially when such abuses undermine America’s credibility and its national interests.

— To what extent does protecting Israel still define U.S. foreign policy in the region?

Do you foresee a time when U.S. administrations will treat Israel as an accountable actor—not just one to be protected?

DZ: American foreign policy should serve American interests. But reading through 80 years of history, it’s clear that Washington often does not pursue its own interests—nor those of any party except the few who profit from chaos.

I would even argue—as I do in the book—that if one of America’s stated goals is to protect Israel’s security, then it is failing at that.

The current security competition which threatens American, Israeli, Iranian, and Arab interests is deeply worrying.

To your question: I believe Israel’s moment of reckoning will come from within Israeli society and from within the global Jewish community. Many supporters of Israel are very unhappy with where things are headed. Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett recently stated that Netanyahu has brought the country to the brink of civil war.

Despite assassinations and high-tech displays of force, Netanyahu has failed to defeat Hamas, Hezbollah, or the Houthis. He’s also failed to bring down the Iranian regime and at this point, I don’t believe China or Russia would allow Iran to fall into chaos.

That internal Israeli reckoning could eventually shift American policy in a more productive direction. But the blame must be shared. Critics of Israel must step up to present a credible political horizon as an alternative to endless war. The Arab Peace Initiative was a vital step in that direction. Now the Arab and Muslim worlds need to seriously revive that vision.

The Iran nuclear issue must be addressed directly, quickly, and firmly through diplomacy. The same applies to the Palestinian issue. In my view, they are deeply linked, especially after the U.S.-Israel-Iran war. China and Russia have a major role to play here as well and they could help to stabilize the region.

— You have wide-ranging interests beyond politics, and I’d like to end by exploring one of them. You founded Microclinic International, which promotes the concept of “positive social contagion.”

Can this concept be applied to political and social change just as it’s used to fight disease?

DZ: That’s a great question! Yes, I’ve done quite a bit of work in public health, including in the Middle East. And what I’ve found is that just as you said good behaviors, like bad ones, are contagious through social networks.

Take smoking. Why do kids pick it up? Because someone influences them—celebrities, media, family, friends, even strangers.

Why do we call the opioid crisis an “epidemic”? Because it spreads via social contagion. Behaviors are socially infectious for better or worse.

Positive social influence can help people quit smoking, eat healthier, and exercise. That’s why we say: Good health is contagious. Spread it.

And yes, I believe the same logic applies to politics.

Friends and family can encourage each other toward violence, apathy, institutional decay, or disinformation.

But they can also use social networks to drive voter turnout, reject violence, speak the truth, and promote civic participation.

What you’re doing here as a social influencer is a prime example of positive social contagion.

This Interview is the first in a series of written interviews with Western scholars whose academic or intellectual work touches on Arab and Western relations. The goal is to understand how the region is perceived through Western eyes and to foster a deeper dialogue grounded in knowledge, not myth.