In the second decade of the new millennium, Egypt underwent one of its most significant political transformations in modern history. It began with the January 25 Revolution of 2011, which toppled a regime that had lasted thirty years, and unleashed an unprecedented opening in the political and party landscape, spanning the full spectrum from the far right to the far left.

But that dream soon curdled into a nightmare. As polarization escalated, the crisis reached its peak on June 30, 2013, when angry crowds took to the streets demanding the removal of the democratically elected president, accusing him of failure and of Islamizing the state. The military, led by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, stepped in, ousted the president on July 3, 2013, and introduced a new roadmap.

Supporters saw this as a corrective to the revolution and a rescue of the country, while opponents considered it a coup against Egypt’s first democratic experiment and a return to military rule.

In any case, this event triggered a political earthquake that dramatically reshaped the landscape. It did more than remove the Muslim Brotherhood from power as the June 30 protesters had demanded—it also killed off the most diverse political experiment in Egypt’s history, undoing the gains won after the January 2011 uprising.

Between the moment of opening and the moment of closure, a deep political crisis emerged — one whose effects persist to this day. In this report, Noon Post shines a light on Egypt’s multiparty landscape during those pivotal years, tracing the major shifts between the dream born in the streets of January and a reality now confined and monopolized.

Before the January Uprising

Under Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt was a one-party state; no new parties were allowed. His successor, Anwar Sadat, allowed a limited political space in the mid‑1970s, giving rise to three parties: the Arab Socialist Party, the Socialist Liberal Party, and the Progressive Unity Party.

In 1978, Sadat founded the National Democratic Party (NDP) as the political arm of his regime. After his assassination, Hosni Mubarak took over the party and retained its grip on all political aspects. Though nominal opposition parties existed, there was no real political pluralism.

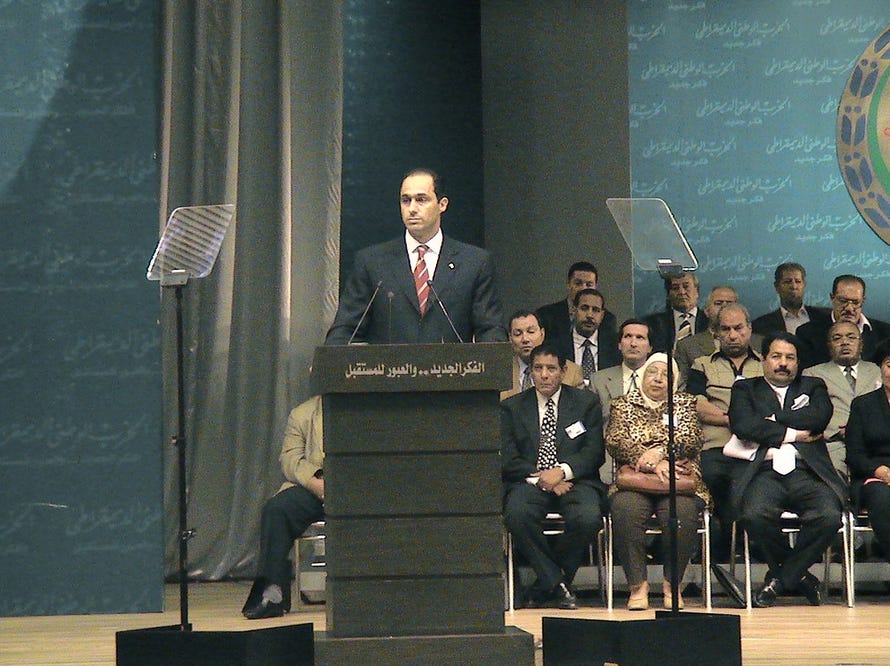

By the early 2000s, two genuine opposition parties appeared: Ayman Nour’s Al‑Ghad (founded in 2004) and the Democratic Front (2007), led by Osama Ghazali Harb after splitting from the NDP. The Muslim Brotherhood also participated through electoral alliances.

Yet, from 2006, political liberalization reversed dramatically—rigged elections, curbs on liberties, and the 2007 constitutional amendments strengthened control over parties via a state‑dominated Party Affairs Committee.

Disillusionment deepened, especially as Gamal Mubarak emerged as a powerful figure backed by business interests, security forces, and cultural elites. Although 24 parties were officially registered, most were paper entities with no popular base. Widespread fraud in the 2010 parliamentary elections—where the NDP seized 420 of 508 seats—together with mounting economic and social crises, set the stage for the January uprising.

Egypt’s Political Spring

The 2011 revolution dismantled not just the regime but the constraints on public space. Freedoms surged: new political entities emerged, revolutionary movements gained ground, and activists established dozens of parties.

Within a year, the number of parties jumped from 24 to 68. New voices from Islamist, Christian, liberal, leftist, revolutionary, Salafi, and Sufi backgrounds entered the scene. The Brotherhood formed the Freedom and Justice Party. The Wasat Party offered a more moderate Islamic option. The Salafi al-Nour Party, a political wing of Alexandria’s Salafi movement, won second place in the 2011‑12 parliamentary vote.

The 2012 presidential elections were historic: open debates, competitive candidates, and the sense that “voices finally mattered.” Numerous post-uprising parties emerged: the Constitution Party, Egypt Strong Party (formed by presidential hopeful Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh), Al-Ghad Al-Thawra, Egyptian Conference Party (Amr Moussa), National Movement Party (Ahmed Shafiq), and the Free Egyptians Party (led by Naguib Sawiris). Ex-NDP figures formed their own, often derisively called “remnants” parties.

Labor, leftist, Nasserist, and secular parties also flourished—Karama, Democratic Labor, People’s Socialist Alliance, and the Communist Party. Mixed liberal-leftist outfits like the Social Peace Party and Egyptian Liberation Party appeared too. Breakaway Brotherhood dissidents founded parties such as Leadership and Renaissance.

Sufi orders entered politics via the Social Tolerance Party. Even elements of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and Jihadi groups formed the Construction and Development Party, the Democratic Jihad Party, and the Islamic Party.

In Cairo, Salafist parties like al-Asalah and al-Raya (led by Hazem Salah Abu Ismail) gained momentum. Five Christian-referenced parties emerged. Youth movements such as April 6 and the Revolutionary Socialists, along with student activism and coalition-building (e.g., youth, human rights, professional groups) energized political life.

The Fall from the Summit

Despite diverse hopes, the post-revolution forces failed to unite over excluding the military from politics. Many liberal and secular parties aligned with the military against Islamists, undermining the popular will and fracturing the progressive path.

A few months into Mohamed Morsi’s presidency, opposition groups—from civil to ex-NDP figures—coalesced into the National Salvation Front. They called for military intervention, rejected Morsi’s proposed roadmap, and demanded early elections.

The military had widespread media backing; anti-Muslim Brotherhood parties supported the Tamarod movement, which mobilized the June 30 protests that culminated in Morsi's ouster on July 3, 2013.

The consequences were clear: the pluralistic moment of post-January politics was crushed. Many marginalized communities were shut out; leftist and liberal parties lost relevance, and Islamist opposition was silenced, imprisoned, or banned. Former January parties splintered under pressure, chose exile, disbanded despairingly, or faced legal persecution.

Though some secular parties had backed the 2013 coup, the regime quickly marginalized them too—engineering an electoral system against them and allowing security infiltration. Meanwhile, pro-regime, security-aligned parties proliferated.

Today, political participation is hostage to security approval: new parties must align with the regime. Parliament has no real oversight role and simply rubber-stamps decisions. In effect, President Sisi has recreated a closed, authoritarian model reminiscent of NDP-era authoritarianism, institutionalized via the 2014 creation of the Future of the Nation Party under military intelligence oversight. Meanwhile, the fundamental questions raised by January—democracy, justice, and the military’s role—remain unanswered.