Karachay-Cherkessia: A Forgotten Republic Grappling with Identity, Poverty, and Russian Dominance

Nestled in the northwestern Caucasus, Karachay-Cherkessia spans 14,300 square kilometers, bordered by Krasnodar Krai to the west, Kabardino-Balkaria to the southeast, and Stavropol Krai to the northeast. Its southern frontier traces the Caucasus Mountains, adjoining Georgia and Abkhazia.

This article is part of our series "Islamic Homelands in Russia," which delves into the histories of Siberia and the North Caucasus republics—Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia—as well as Tatarstan and Bashkortostan.

These regions, home to approximately 25 million Muslims, are examined through their social, religious, and political landscapes, all under the overarching influence of Russian authority.

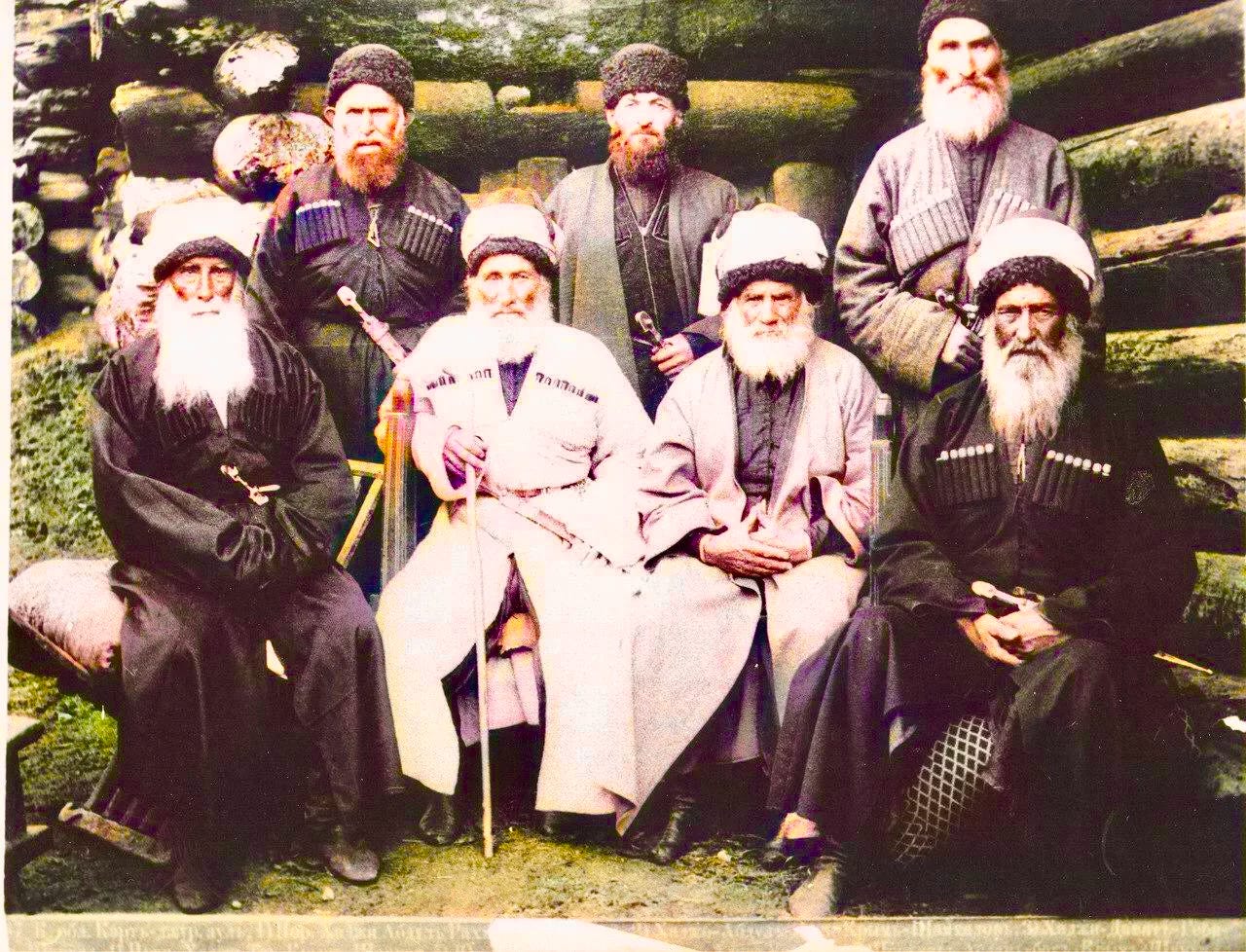

Ethnic and Religious Mosaic

Despite its modest size, Karachay-Cherkessia is among the most ethnically and religiously diverse areas in the North Caucasus. The republic recognizes five official languages: Russian, Kabardian Circassian, Abaza, Karachay-Balkar, and Nogai.

As of the 2024 census, the population stands at 468,400, with Karachays comprising 44.38%, Russians 27.55%, Circassians 13%, and others 15%. Muslims, predominantly Hanafi Sunnis, make up 64% of the populace, while 13% adhere to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Ethnic groups are geographically distinct: Karachays inhabit the eastern highlands, Circassians the lowlands, and Russians the western plains. This segregation extends to administrative divisions, reflecting the republic's complex ethnic tapestry.

Karachay-Cherkessia mirrors Kabardino-Balkaria in its ethnic composition but in reverse; while Circassians dominate Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachays are the majority here. Both Karachays and Balkars share Turkic roots and language, yet Soviet-era policies artificially divided them into separate republics during the 1930s.

Natural Wealth Amidst Socioeconomic Struggles

The republic boasts abundant natural resources—gold, marble, coal, clay—and a rich hydrological network with 172 rivers and 130 lakes. Forests, diverse flora, and fertile lands support agriculture and livestock. Mountains cover 80% of the territory, making it a haven for eco-tourism.

However, beneath this natural bounty lies a deep socioeconomic crisis. Widespread poverty, corruption, and unemployment plague the region, with 25% of residents living below the poverty line. Declining birth rates, rising mortality, and emigration exacerbate the demographic decline, as skilled workers leave for central Russia and Europe.

Russia capitalizes on the region's economic hardships, offering up to 2 million rubles (€20,300) to young men who enlist to fight in Ukraine. Notably, Karachay-Cherkessia lacks an airport and direct rail links to Moscow, underscoring its infrastructural neglect.

Traditional clan structures remain influential, with Karachays dominating government roles. Circassians and Abaza, though minorities, maintain well-organized communities. Ethnic tensions persist, occasionally erupting into conflicts and highlighting the fragile interethnic relations shaped by historical grievances and Soviet-imposed boundaries.

Historical Trajectory

The Mongol invasions in the 13th century and Timur's campaigns in the 14th devastated the region. Islam spread through Ottoman and Crimean Tatar influence, gradually supplanting Christianity. In the 15th century, the Karachay principality emerged, later falling under Russian control after the 1828 Battle of Khasaouk.

During World War II, Stalin accused the Karachays of collaborating with Nazis, leading to the 1943 deportation of nearly 70,000 individuals to Central Asia under Operation Seagull. Approximately 19% perished during exile.

The Karachay Autonomous Oblast was dissolved, and its territories redistributed. In 1957, survivors were allowed to return, only to find their homes occupied and their lands altered, fueling long-standing resentment.

Post-Soviet Challenges

By 1989, Karachay-Cherkessia was an autonomous region within Stavropol Krai, with a complex ethnic mix: 42% Russians and Cossacks, 31% Karachays. Infrastructure remained outdated, and environmental degradation was rampant. Land disputes, especially between Karachays and Cossacks, intensified.

In 1990, Karachays declared autonomy, seeking to separate from Cherkessia and unite with Balkaria. Circassians, comprising about 12% of the population, advocated for joining Kabardino-Balkaria. Despite a 1992 referendum opposing division, ethnic tensions and sporadic violence persisted throughout the 1990s.

Religious Landscape Under Russian Oversight

The 1990s saw the rise of Islamic movements, with some Karachays adopting Salafism after fighting alongside Chechens. This led to clashes with traditional religious authorities.

Today, Salafi groups face suppression under the guise of anti-extremism, with Moscow controlling religious appointments and online content. Recent bans on the niqab are perceived as broader efforts to curb Islamic expression.

Additionally, Russian policies aim to marginalize native languages. Amendments to the constitution prioritize Russian in education, relegating indigenous languages to secondary status. Russian dominates official institutions and media, further eroding cultural identities.

While separatist activities have waned compared to neighboring regions, Karachay-Cherkessia continues to grapple with the legacies of Soviet repression, economic marginalization, and cultural suppression.

Despite limited media attention, the republic's quest for identity and autonomy remains a poignant chapter in the broader narrative of Russia's diverse and complex federation.