In Israeli media circles, the newspaper Maariv is often referred to as "Israel's iconic newspaper," with its founder hailed as "the godfather and father of Israeli journalism." Its news is served to Israeli readers on a silver platter, accompanying them like a nightly ritual with Western-style news coverage tailored to their preferences and political sensibilities.

This reputation is not incidental. In its first two decades, Maariv reigned supreme in Israeli journalism, dominating the media landscape with little serious competition. It served the policies of its founder faithfully, offering news reports rich in detail unavailable elsewhere, thanks to its domestic and international proximity to decision-making circles and its central position in the arena of Israeli ambition.

This article continues our series, "Haaretz and Its Sisters," tracing the evolution of Israeli media—its newspapers, origins, challenges, and its military-like roles cloaked in journalistic language. The series explores their influence in settlement, displacement, normalization, and the psychological shaping of generations through wars, peace accords, and revolutions.

This installment focuses on Maariv, the rebellious paper that indelibly shaped the editorial tone of Israeli journalism. Nationally and internationally, Maariv charted a course from word to battlefield, supporting settlement, displacement, and normalization, while inciting against Arabs and Palestinians—until its more recent reconfiguration on the Israeli media map.

"Evening News" and the Challenges of Inception

In 1948, nine years after the founding of Yedioth Ahronoth, and eight years into a new editorial era under German-Jewish editor Azriel Carlebach, tensions between Carlebach and the Moses family reached a breaking point. The root of the conflict lay in economic, managerial, and editorial disagreements. The Moses family believed Carlebach's editorial style failed to generate profits, while Carlebach believed he was cultivating a loyal readership committed to the paper's editorial vision.

In what Israeli journalism history calls "the great coup," Carlebach gave Noah Moses an ultimatum: hand over the paper or face a mass resignation. Moses refused, and on February 13, 1948, Yedioth Ahronoth experienced the largest collective resignation in its history. Thus was born Maariv, emerging from the ashes of that split.

Among the resigning staff were some of Yedioth's top writers, including Shlomo Ben Yisrael, Eliyahu Carlebach, Max Nussbaum, and Shalom Rosenfeld. The resignations extended beyond the editorial team, crippling printing and distribution operations and paralyzing the paper for years.

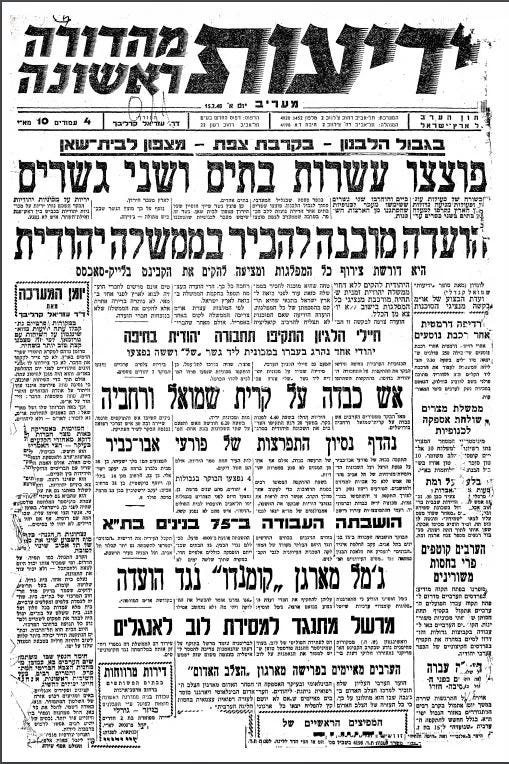

But what seemed like internal strife was, in fact, a calculated move. Carlebach had long harbored ambitions of launching a competing paper. Using an earlier license he had obtained in 1937, he seized the opportunity. On February 14, 1948—the very next day—he and his team published the first issue of Yedioth Maariv, meaning "Evening News."

The debut issue carried fiery headlines such as "Two Bridges and Several Homes Blown Up in Safed" and "Committee Formed to Recognize the Jewish Government." The paper adopted the slogan "Evening News from the Land of Israel" and reused serial stories previously published in Yedioth, as though it had never stopped serving its readers.

Maariv continued the serious journalistic ethos Carlebach had built: diversified news formats, exclusive reports, and engaging stories, all aligned with global newswriting standards. Carlebach's name appeared on the front page, symbolizing journalistic integrity and editorial modernity.

Rejecting partisan support and wealthy backers, Maariv was launched as a cooperative, with shares held by its founding journalists. Shalom Rosenfeld, Shmuel Schnitzer, David Lazar, David Giladi, Uri Kesari, and Aryeh Disenchik were among those who rotated editorial responsibilities for over a decade and a half.

In its first year, Maariv made major strides. It attracted 30,000 daily readers—a significant figure at the time—and engaged in a series of legal battles with Yedioth Ahronoth, most notably over its original name, Yedioth Maariv. A court ruled it must drop "Yedioth," leaving it with the enduring title Maariv, or "Evening."

One of Maariv's first impactful moves, particularly in influencing Arab audiences, was its bold coverage of Arab affairs. In late 1948, it published a scoop titled "Abdullah Calls for Peace with Israel," beginning its calculated efforts to shape regional public opinion through a blend of brash journalism and strategic leaks.

Maariv: A Camp or a Newspaper?

By the end of its first year, Maariv had assembled a formidable team of Ashkenazi Jewish journalists, many with roots in the British Mandate period and experience in right-wing newspapers like Davar, HaBoker, and Yedioth Ahronoth.

Carlebach set a clear editorial agenda to reflect the voice of the "average Israeli": political neutrality, avoidance of party affiliation, promotion of civil and agricultural education in the Yishuv and kibbutzim, and a militaristic language in news reporting. Though leftist voices were included, Zionism remained the ideological bedrock.

Yet internal disputes emerged over this "party neutrality." Editors with varying political backgrounds clashed over the newspaper's alignment with Israel's emerging political system.

Aryeh Disenchik, who succeeded Carlebach as editor-in-chief, was a key figure in the Revisionist Zionist movement and served as secretary to Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Shalom Rosenfeld, his successor, was similarly aligned with right-wing nationalist ideologies and had deep ties to the Irgun.

Their backgrounds rooted Maariv in hardline Zionism. Although officially unaffiliated with any party, the paper consistently supported settlement and military action. Its language appeared civilian but was militaristic in substance.

Several of its editors, like David Lazar and David Giladi, had military or Zionist agency backgrounds, and their combined experience anchored Maariv firmly in the ideological camp of militant Zionism.

During the ethnic cleansing campaigns, Maariv ran celebratory headlines like "In Two Weeks, No Arabs Will Remain in Haifa" and published maps aligned with Revisionist Zionist visions of Greater Israel. Even its coverage of Theodor Herzl's reburial in Jerusalem was filled with hyper-nationalist rhetoric.

Its coverage of Arab affairs was often mocking. A Syrian coup was headlined as "The Leader is Dead," and a visit by King Abdullah of Jordan to London became "Abdullah in London," speculating salaciously about family drama.

Throughout its first decade, Maariv maintained influence, launched a teen weekly, and featured prominent columnists like Menachem Begin and David Ben-Gurion. After Carlebach's death, Disenchik maintained its ideological course, while expanding its international presence, including distribution in New York and the launch of arts and entertainment magazines.

Military experience often became a path to journalism at Maariv. Many reporters, including paratroopers like Uri Dan and Eli Landau, transitioned directly from battlefield to byline, helping cement the genre of Israeli military journalism.

Several of its journalists moved into politics, including five who became Knesset members. Prominent figures like Shimon Peres and Ariel Sharon also wrote for the paper.

Srulik: Zionism Needs a Mascot

Beyond journalism, Maariv reinforced Zionist identity through cultural and cartoon characters. The most iconic was "Srulik," created by caricaturist Kariel Gardosh (Dosh), a right-wing artist with ties to the Lehi underground.

Srulik, modeled as a ten-year-old boy symbolizing the young state, wore a "tembel" bucket hat associated with pioneering settlers and sandals known as "Biblical sandals," a hallmark of Zionist identity.

Depicted alternately as religious or secular, Srulik was always Zionist. In war, he transformed into a soldier; in peace, he relaxed by the Mediterranean with a weapon in one hand and a pen in the other. Debuting in 1951, he mirrored the state itself.

Later cartoons showed Srulik grappling with internal divisions, symbolizing Israel's societal fractures. Despite the satire, Dosh used Srulik to chronicle the Israeli-Arab conflict and peace efforts, often casting Arab leaders as snakes, embodying Zionist suspicion.

The character's influence extended internationally, with spinoffs like Marvel's Sabra and Israeli children's characters. His attire came to represent frugal, pioneering Israel, and inspired fashion lines by Israeli brands.

The End of a Golden Era

Maariv's decline began during the 1967 war, when Yedioth Ahronoth distributed free copies to soldiers, regaining dominance. By the 1980s, Maariv's traditional style seemed outdated compared to Yedioth's livelier approach.

By the 1990s, Maariv's circulation dropped below 100,000, and design changes like a custom font, "Kislev," failed to reverse the trend. In a desperate bid for scoops, it published false reports, like the fabricated 1989 defection of Syrian pilot Bassam Adel.

Financial instability followed. Ownership passed to mogul Robert Maxwell, who modernized the paper with full-color printing but died soon after. Businessman Ofer Nimrodi took over, but conflicts with editors and wiretapping scandals damaged its reputation.

Investigative journalism gave brief reprieve, with exposés on the use of banned silicone in milk and the destruction of Ethiopian blood donations. But scandals involving political favors, financial mismanagement, and mass layoffs led to its collapse in 2012.

By 2014, after years of instability and multiple ownership changes, Maariv was sold to the owner of The Jerusalem Post for just four million shekels. It now appears under various brands like Maariv Hashavua and Maariv Sof Hashavua, all part of The Jerusalem Post group.

Where Does Maariv Stand Today?

As the saying goes: "In fierce battles, the weakest fall first." That may explain Maariv's weakness but not its downfall. The very ideology that once gave it power became ubiquitous across Israeli media. What once made Maariv unique now echoes everywhere—in political speeches, social media, and newsrooms.

Its apologetic framing of Nakba atrocities as "collateral damage" mirrors today’s unapologetic Israeli narrative. During the Qibya massacre in 1953 and the Kafr Qasim massacre in 1956, Maariv justified the killings or dismissed them as misunderstandings.

Rooted in the settler project, the paper devoted entire sections to what it called "agricultural and security pioneering," essentially promoting Jewish Agency land grabs. After 1967, it openly supported annexation as an existential right.

It also preserved its Eurocentric bias. Editor Shmuel Schnitzer once decried the entry of Ethiopian Jews as a public health threat. Few non-Jews or non-Ashkenazis worked at the paper, and those who did, like Jackie Khoury or Suleiman al-Shafi, had to prove political loyalty to be accepted.

Until its final breath, Maariv remained iconic in form, nationalist in substance, and Zionist in narrative. But it faded from a populist powerhouse to a historical archive, no longer a voice of national truth but a faint echo in an extremist choir.

As Yuval Kartiel of Herzliya College said: "Maariv reflects the evolution of Israeli society. When we look at it, we see ourselves... It's an Israeli story."

Some may say Haaretz, Israel Hayom, or The Jerusalem Post better reflect that story today. But Maariv unquestionably served the Zionist project well, giving it a unifying Hebrew voice unmatched—until now, when a different voice is being written in blood.

Perhaps Yuval is right. Perhaps, one day, the whole story—born of conspiracy and sustained by violence—will come to an end, and be forgotten.