Despite their festive and spectacular nature, sporting events are not merely sources of entertainment and excitement. They also provoke serious debate around the economic viability of hosting such large-scale competitions particularly in countries grappling with socio-economic challenges. For a segment of the population, these tournaments are seen as extravagant ventures that neglect more urgent development priorities.

In response to critics who dismiss such concerns and who argue that sports, especially football, merely serve to distract the masses French scholar Christophe Bromberger asserts in his book Football: The Most Serious Triviality in the World that sports events do not have the power to anesthetize societies to their problems. He cites the example of widespread protests in Mexico during its hosting of the 1986 FIFA World Cup as evidence.

Morocco, which is currently hosting the Africa Cup of Nations (until January 18, 2026) and preparing to co-host the 2030 World Cup with Spain and Portugal, finds itself at the heart of this same dilemma. Months before the African tournament kicked off, Moroccan members of Generation Z took to the streets, calling for public spending to prioritize essential sectors like healthcare and education over sports infrastructure.

The Moroccan government, however, defended its decision through Fouzi Lekjaa President of the Royal Moroccan Football Federation and Minister Delegate for the Budget emphasizing the anticipated economic benefits of hosting a global event.

Why Does Sport Spark Public Outrage?

For decades, major sporting events like the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games have been used as tools to polish the reputations of political regimes a practice often referred to as “sportswashing.”

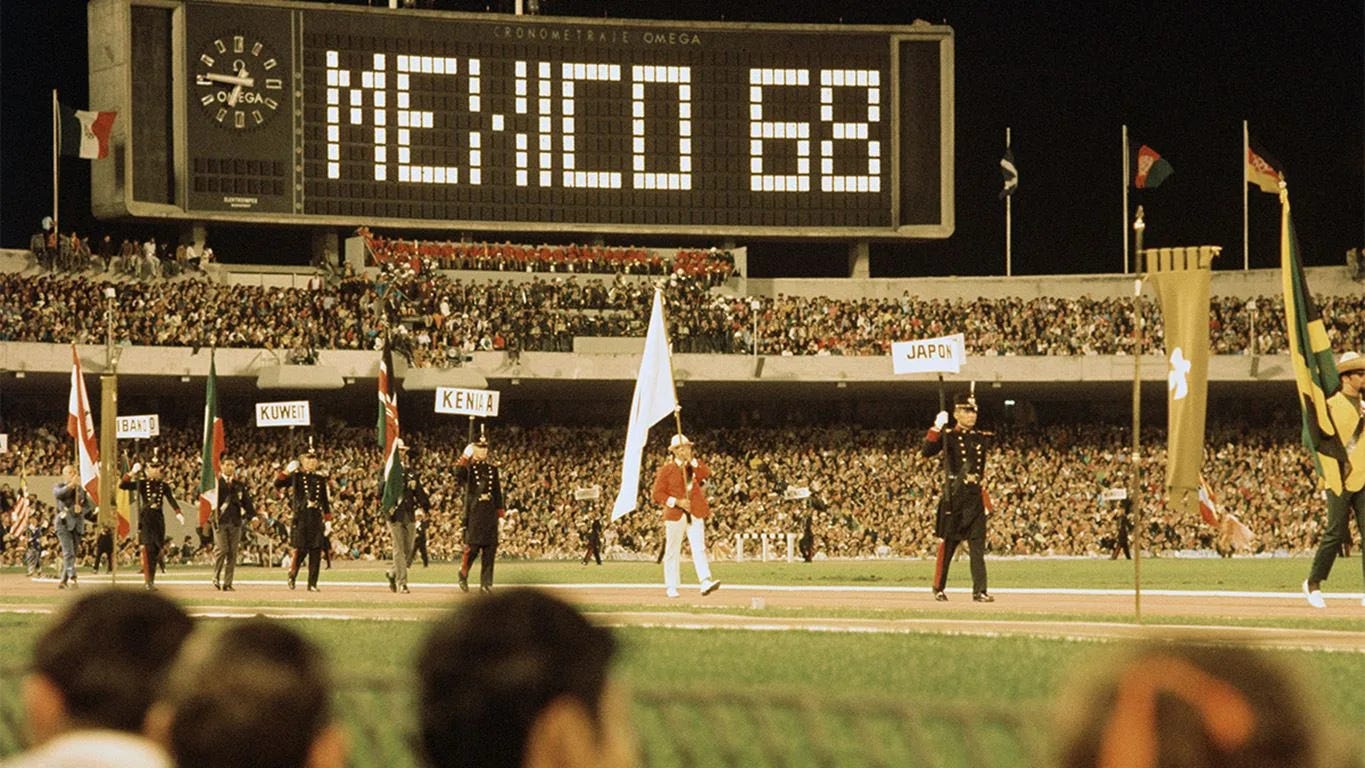

Notable examples include Nazi Germany’s hosting of the 1936 Olympics under Hitler, Fascist Italy’s hosting of the 1934 World Cup under Mussolini, and Mexico’s hosting of the 1968 Olympics under authoritarian president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. The Mexican case, in particular, reveals a tragic paradox: just ten days before the Olympic opening, Mexican security forces brutally suppressed a peaceful student demonstration in Tlatelolco Square, leaving hundreds dead in what became known as the Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2, 1968.

In an effort to understand the public discontent that often accompanies such events, sports policy researcher Moncef El Yazghi pointed to Brazil as a particularly striking example. Despite being a nation passionate about football, Brazil saw mass protests ahead of the 2014 World Cup, as thousands of residents were evicted from their homes to make way for tournament infrastructure.

According to El Yazghi, these protests stem from “the increasing ability of populations to organize and voice dissent, combined with the evolution of communication tools. Today, there are numerous ways to oppose the hosting of sporting events that are at odds with a country’s internal situation. There is also a tendency to blame football and related projects for policy failures even though issues in education, healthcare, and social welfare predate these events.”

Sports only became a serious subject of academic study with the emergence of sports sociology and the contributions of British historians and social scientists. Key figures in the field include Dutch anthropologist Johan Huizinga, along with Eric Dunning and Norbert Elias.

On the question of why popular anger often erupts around major sporting events, sports sociologist Abdelrahim Bourkia told Noon Post that countries witnessing such protests often face deep social inequalities. In such contexts, investments in sports infrastructure are viewed unfavorably when compared to the fragility of sectors like education and health.

In Bourkia’s view, football in particular becomes a mirror reflecting broader dysfunctions budgetary imbalances, skewed policy priorities, and the absence of equitable resource distribution.

Tournaments and the Economics of Risk and Reward

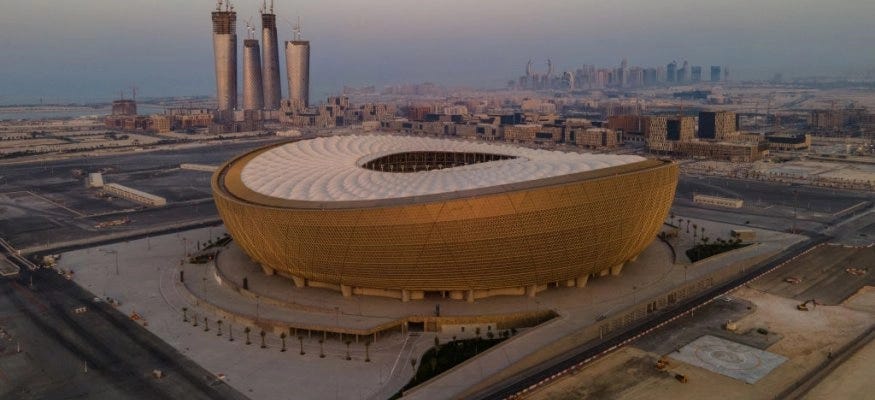

Arguments for and against hosting major sports tournaments almost always revolve around their economic impact. Proponents often cite the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, which delivered significant and long-term financial returns. According to an IMF report, Qatar invested between $200 billion and $300 billion in a decade-long infrastructure program, of which only $6.5 billion was allocated to stadium construction. The rest was channeled into broader infrastructure and economic diversification.

Speaking to Noon Post, economist Ali Haddada emphasized that the economic gains of such events depend on how effectively host countries transform them into long-term opportunities. “Hosting becomes profitable,” he explained, “when the event is integrated into citizens’ daily economic lives through a development strategy that extends beyond the tournament itself by creating infrastructure that remains useful and by leveraging the event to boost tourism and investment over the medium and long term.”

Yet critics counter these optimistic forecasts with hard numbers. For instance, every Olympic Games held between 1960 and 2020 overshot its declared budget by an average of 172%.

Academic scrutiny of mega-events has also intensified. One of the most influential critiques comes from American researcher and former Olympic athlete Jules Boykoff, whose theory of “celebration capitalism” argues that these events allow private interests to reap profits while the public bears the financial risks. Boykoff highlights the inflation of projected returns, underestimation of true costs, and the diversion of public resources from essential services to showcase projects as key flaws.

Ali Haddada warns of additional risks: “There’s a real danger of cost overruns, pushing states to raise taxes or take on more debt burdens that will ultimately fall on citizens. And in countries where political and economic elites are closely intertwined, such as in much of the Arab world, public procurement related to these events is often plagued by corruption.”

Morocco and the World Cup: Legitimate Protests or Premature Panic?

Morocco is banking on the 2030 World Cup to drive broad-based development. Plans are underway to double airport capacity to 80 million travelers annually by 2030, up from 38 million today.

According to a report by the Moroccan Government Action Observatory, hosting the tournament could increase GDP by 0.5% to 1% annually translating to an additional $3–4 billion—and generate $2–3 billion in tourism revenue during and after the event.

But these projections have done little to assuage the concerns of Morocco’s Gen Z, many of whom launched nationwide protests in September 2025. Among their demands: more investment in critical sectors like health and education instead of spending on high-profile sporting events particularly the World Cup.

Such concerns are echoed in academic circles. Moroccan economist Najib Akesbi cautioned against the financial risks of hosting the tournament, drawing comparisons to Greece’s economic collapse following the 2004 Athens Olympics.

Akesbi argues that Morocco already fiscally strained due to the COVID-19 pandemic, recurring droughts, and an increasing reliance on debt risks mortgaging its future for limited and short-lived returns, especially as job creation is likely to be temporary and tourism booms unsustainable post-event.

In response to these criticisms, sports policy expert Moncef El Yazghi insists that preparations extend far beyond stadiums and can catalyze comprehensive development through job creation and infrastructure expansion.

Speaking to Noon Post, El Yazghi argued that hosting the tournament could compress 20 years of development into just six, citing studies that show Morocco could “gain 14 years” through accelerated implementation. He added that FIFA’s strict oversight mechanisms could act as a more effective accountability tool than Morocco’s traditional parliamentary checks since noncompliance could result in the country losing its right to host.

Sociologist Abdelrahim Bourkia highlighted the dual dimensions of Morocco’s ambitions. Externally, the country seeks to project itself as a stable, open, and secure regional power. Internally, there are heightened public expectations that the tournament will deliver real economic benefits.

Bourkia stressed the need to balance these objectives strengthening Morocco’s international standing while ensuring social justice and sustainable development at home. He argued that this is possible through transparent governance, sound financial management, and a genuine commitment to equitable growth.