Marwan Barghouti was never an ordinary leader in the Palestinian struggle; he has always remained intricately connected to the aspirations of his people, and to their direct suffering. From his youth, he engaged in every phase of the uprising shifting arenas of resistance until the occupation’s prisons and solitary confinement cells became his main battlefield over the past two decades, as Israel sought to erase his presence and diminish his symbolic potency as both a fighter and a national icon.

Israel’s revenge, flagrantly disregarding international law and humanitarian norms regarding detainees, reached performative extremes meant to intimidate a key figure of Palestinian leadership. This reached a climax in the widely circulated video of far‑right minister Itamar Ben‑Gvir storming into Barghouti’s cell, threatening him in a deliberate violation of his symbolism and national significance.

Since his re-arrest in 2002 and sentencing to five life terms, Marwan Barghouti, alongside his fellow prisoners, has become a cross-factional national emblem. He remains the leader who blends field-based resistance with political leadership in the Palestinian Liberation Organization and Fatah.

You cannot understand Barghouti's journey without acknowledging the interplay between street mobilization and political acumen, nor without recognizing how his prolonged imprisonment has transformed his symbolic weight and significance.

From Kobar: The Cradle of His Early Struggle

The village of Kobar, northwest of Ramallah, symbolizes a wellspring of resistance—a “reservoir of heroism”—from which numerous martyrs and imprisoned leaders have emerged. Located about 10 kilometers from Ramallah and nearly 20 kilometers from occupied Jerusalem, with vistas of both Jerusalem and al‑Aqsa Mosque overshadowed by settlements, Kobar shaped Barghouti.

Born there on June 6, 1959, he was raised in an environment steeped in family ties to early armed cells in the West Bank, some of whom were among Israel’s first prisoners serving life terms.

Marwan did not linger in childhood. Long before most peers, he immersed himself in the struggle, showing early signs of leadership. He joined Fatah at age 15 and was first imprisoned in 1976 for two years for his involvement, followed by further arrests and intermittent releases until 1983.

He completed his high school education at Al‑Prince Hasan School in Birzeit during these cycles of detention and study disruptions. In prison, he learned Hebrew and developed proficiency in French and English, enriching his general knowledge.

By 1986, Israel began actively pursuing him; during the 1987 First Intifada, he rose to prominence until he was arrested and expelled to Jordan under Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s policy of exile. He later resettled in Tunisia, earning a B.A. in History and Political Science and an M.A. in International Relations, before being re-arrested in April 2002 while lecturing at Al‑Quds University in Abu Dis.

In prison, particularly in solitary at Hadarim, he clandestinely pursued a Ph.D. in Political Science at Cairo’s Institute of Arab Research and Studies completing his dissertation and smuggling it out with his lawyer’s help around 2010.

Barghouti has authored several important works, including The Promise, Resistance of Captivity, A Thousand Days in Solitary Confinement, and National Unity: The Law of Victory. On April 18, 2017, he succeeded in sending an article to The New York Times on Palestinian Prisoners’ Day, denouncing Israeli brutality in prisons.

He also published his doctoral dissertation, titled Legislative and Political Performance of the Palestinian Legislative Council and Its Contribution to the Democratic Process in Palestine (1996–2006).

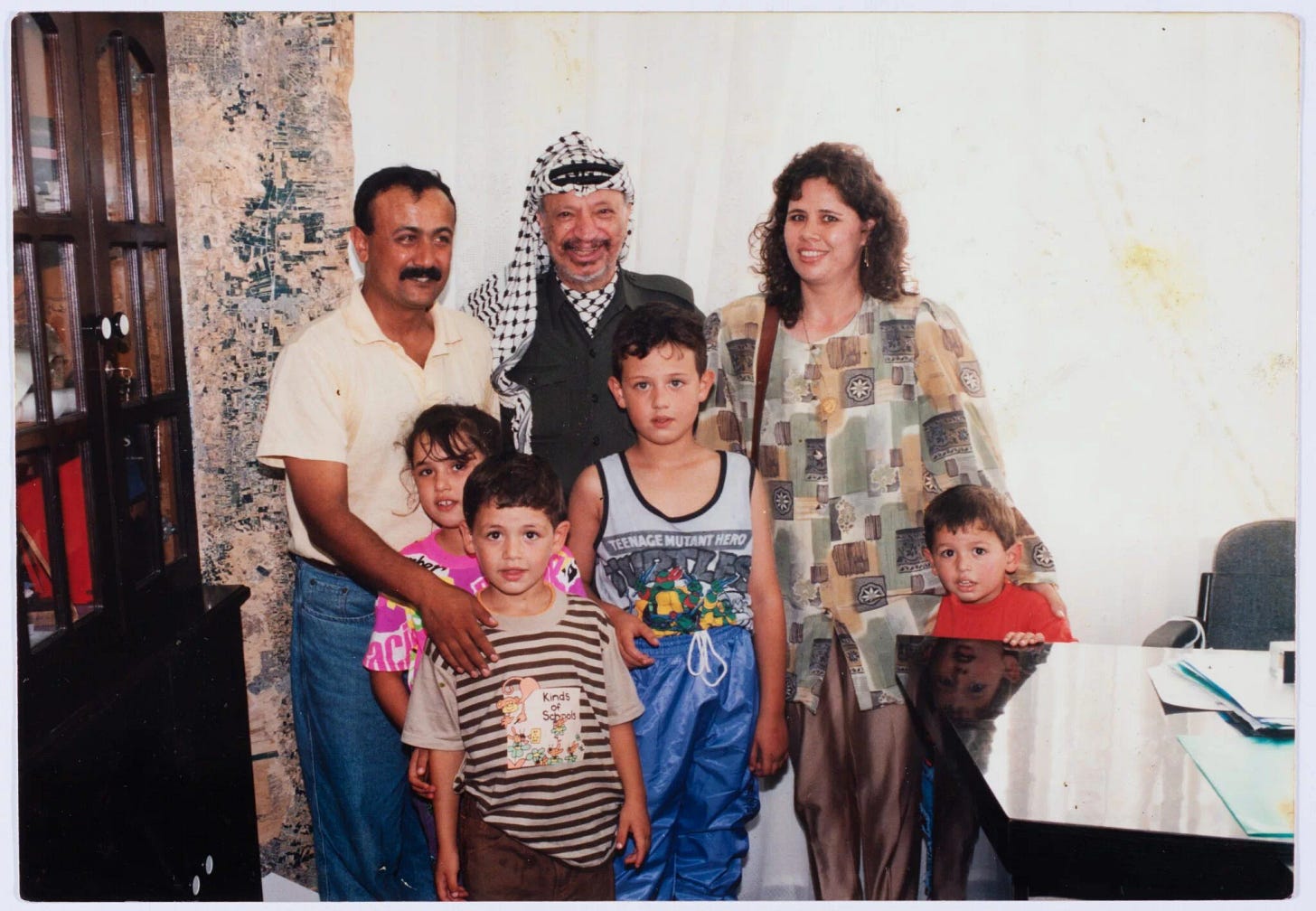

Known as "Abu al‑Qassam," he is married to attorney and social activist Fadwa Barghouti, who has emerged as his political and media advocate both within Palestine and internationally.

Between Student Activism and Imprisonment

Following his early imprisonment spells from 1976 to 1983, Barghouti immediately enrolled at Birzeit University where he was elected student council president for three consecutive terms. He was instrumental in founding the Fatah Youth Movement (Shabiba) in the early 1980s, which played a central role in the mass mobilization of the First Intifada.

Despite continued Israeli repression—including arrests in 1984 and 1985, harsh interrogations, house arrest, and administrative detention—his prominence grew. In the Intifada’s unified national leadership, he became a central figure and was subsequently exiled.

A Young Face in Fatah Leadership

In Tunisia, Barghouti worked closely with Salah Khalaf (Abu Jihad) and held leadership roles in the PLO’s Upper Committee of the Intifada and Fatah’s Western Sector leadership. At Fatah’s 1989 General Congress, he was elected to the Revolutionary Council—the youngest member among some 1,250 delegates.

Returning to the Occupied Territories in 1994, he quickly rose to become deputy to Faisal al‑Husseini and Fatah’s secretary in the West Bank. He then spearheaded a massive organizational revitalization of Fatah, overseeing over 150 regional conferences that reshaped its internal structures and laid the groundwork for increased democracy and the Sixth General Congress.

Elected to the Palestinian Legislative Council in 1996 with over 12,716 votes in Ramallah and al‑Bireh and becoming its youngest lawmaker, he played an active role in parliamentary committees and anticorruption work.

He also fostered grassroots ties through community meetings and infrastructure-focused initiatives, especially for girls’ schools. Barghouti co-founded and chaired the first French–Palestinian parliamentary friendship group, enhancing bilateral relations.

Second Intifada and Renewed Resistance

Following the collapse of the Oslo process and the outbreak of the Second Intifada in September 2000, Barghouti called for continued popular and political resistance, stating emphatically, "Fatah’s arms remain present—and they will be maintained until freedom and independence are achieved."

He was omnipresent in demonstrations, funerals, and media discussions, criticizing security coordination and advocating protection for civilians and activists. By 2001, Israel had accused him of leading the al‑Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades and allegedly organizing attacks, including an attempted assassination in August that killed his aide.

A year later, on April 15, 2002, he was captured in Ramallah during Operation Defensive Shield—soon followed by provocative remarks from senior Israeli officials celebrating his arrest with deadly rhetoric.

A New Arena of Struggle

After prolonged interrogations and trial, Barghouti was convicted in 2004 under the doctrine of “general responsibility,” as Fatah’s secretary in the West Bank, holding the group accountable for actions by the Brigades.

The Tel Aviv Central Court sentenced him to five life terms plus forty years the maximum penalty. In his closing statement, Barghouti called the verdict unlawful and likened it to a war crime.

In September 2024, he sustained severe injuries from guard violence in Megiddo prison adding to his total of 28 years incarceration.

From Prison Cell to Presidential Contender

Despite decades behind bars, Barghouti has remained politically dynamic. In 2003, he proposed a ceasefire initiative that paved the way for political achievements like the 2006 Cairo agreements and legislative elections. He led Fatah’s list in those elections and advocated internal party reform, democratic leadership elections, and the ousting of corruption.

He was elected to Fatah’s Central Committee in 2009 but was later blocked from becoming deputy leader in the 2016 General Congress despite winning some 70% of votes, a move his wife called capitulation to Israeli pressure.

In January 2021, he announced his intent to run for the presidency after electoral dates were set, positioning himself as a serious challenger to President Mahmoud Abbas. Polls repeatedly show him leading potential three-way contests, and international mediators and Hamas regard him as a heavyweight figure in prisoner-swap negotiations. Despite this, Israeli and Palestinian Authority officials opposed his release.

In mid‑August 2025, the controversial prison visit by Itamar Ben‑Gvir was widely condemned as a provocation and symbol of the fear Barghouti inspires: despite appearing frail and exhausted, he remains unshaken—and his leadership potential unsettles both the Israeli right and those invested in preserving the PA’s status quo.