Mechanisms of Redemption from Holocaust Shame: A Psychoanalytical View of Germany’s Bias Toward “Israel”

“From the German debates on Israel and Palestine, you learn little about the Middle East—but a lot about Germany,” says political science professor Daniel Marwecki, author of Germany and Israel: Whitewashing and Statebuilding. The book provides an excellent analysis of the relationship between Germany and “Israel,” highlighting several psychological aspects that inspired this article.

The author notes that discussions around “Israel” in Germany are psychological and social projections, with “Israel” serving as the object of projection, onto which different aspects of German identity are cast, as we will explain.

In a previous article, we discussed the Holocaust complex in Germans and noted that the German people suffer from feelings of guilt and shame due to the Holocaust. The new German identity, since reunification, has replaced unbearable feelings of guilt and shame with pride in how the past was confronted and in supporting Holocaust victims. We also provided a brief psychological analysis of Germany’s stance toward “Israel.”

In this in-depth article, we will go a layer deeper and expand the psychological analysis of Germany’s position on “Israel.”

Defense Mechanisms

Psychological defense mechanisms are fundamental to psychoanalysis and psychodynamics. These are unconscious processes that operate within a person to protect them from becoming aware of morally condemned, socially unacceptable, or personally distressing emotions or urges—whether rejected by the self or others.

Defense mechanisms aim to keep distressing emotions in the unconscious so that a person does not have to confront them, thereby preserving psychological integrity. Every human necessarily uses psychological defenses constantly, and this is essential to continue living and adapting.

However, some mechanisms have pathological effects, lead to harmful adaptations, or reinforce immoral or even criminal behaviors. Originally individual phenomena, defense mechanisms can evolve into collective phenomena, especially during a nation’s historical turning points, as we will see.

We will elaborate on three specific defense mechanisms among Germans. These mechanisms overlap, but we will aim to clarify each separately. The article also references historical contexts and examples that illustrate these mechanisms and aid in understanding them.

Historical Overview

Germany emerged from World War I with a humiliating defeat against the Allies (Britain, France, and the US). Four percent of its population perished, it suffered catastrophic famine, and was held fully responsible for the war, obligated to pay massive reparations—equivalent to 40,000 tons of gold, which it only finished paying in 2010.

The suffering of war and its aftermath naturally created feelings of humiliation and injustice among Germans, who saw themselves as victims. Germany then regained power and initiated World War II, driven in part by its victim mentality and a desire for compensation and victory. But Germany lost again—this time in the largest war in history.

Most major and mid-sized cities were destroyed. The people suffered immensely during and after the war. Ten percent of Germany’s population died. Millions were displaced or left disabled. At the war’s end, Soviet soldiers raped between one and two million German women. Germany was again obligated to pay vast reparations.

It is natural for a nation that suffered such a loss to feel deep oppression and injustice, and to see itself as a war victim. After all, civilians do not control foreign policy or military decisions. But today’s Germans are not allowed to see themselves as victims and are pressured to repress that sense of victimhood.

All nations that suffer during war develop a sense of victimhood. The Soviet Union, for example, lost more people than Germany. But the key difference is that the Soviets emerged victorious, achieved their aims, and became a global superpower.

Germany, by contrast, lost everything—power, prestige, and the war itself. It surrendered to its enemies, who then occupied and divided it. East Germany fell under Soviet influence and joined the Warsaw Pact; West Germany aligned with the US and joined NATO—all aimed at permanently neutralizing the German threat and limiting Germany’s power.

Yet today, any nation may see itself as a war victim—except Germany. For Germans, the dominant narrative is that they were perpetrators, not victims, because of their role in the Holocaust, which is seen as the most horrific atrocity in history. As a result, Germans are expected to repress any sense of national victimhood and instead confront the fact that they were not only humiliatingly defeated, but also committed the Holocaust.

Identification with the Victim

This is the first defense mechanism.

Germany’s catastrophic defeat, destruction, and surrender in World War II had devastating consequences for the nation. The people endured unimaginable suffering. Naturally, a country that was utterly destroyed, its people displaced and starved, and then surrendered, would develop a strong sense of suffering and victimhood. But for Germans today, describing themselves as victims is condemned and forbidden. Doing so is immediately interpreted as evading responsibility for the Holocaust and is thus seen as a form of antisemitism—strongly denounced in Germany.

Such intense emotions must find an outlet. Therefore, Germans tend to exaggerate the suffering of Israeli Jews today, then identify with that suffering. They describe and react to Israeli suffering with strong emotional investment—as if they themselves were the victims.

Likewise, a defeated and humiliated nation longs for victory and the restoration of power. But today, hostility toward the Allies is unthinkable for Germans. Germany is considered subordinate to the United States. Hence, Germans redirect their desire for military strength and victory toward Israel’s enemies, identifying with Israel once more. They rejoice when Israel triumphs, as if they themselves have achieved victory.

Thus, Germans identify with Jews—specifically with “the State of Israel”—in at least two ways:

– A longing for strength and victory, and pride in military achievements.

– A sense of victimhood.

In both cases, Germans project elements of their identity and history onto the Middle East, as we will explore in the next mechanism, projection.

Why does this identification occur specifically with “Israel”? Because identification with the victim is a defense mechanism aimed at repressing hostility or guilt toward that victim. By identifying with the victim, the victim becomes a representation of the self, and any hostile feelings toward them are buried in the unconscious. Thus, Germans’ identification with Israel serves to repress long-standing antisemitism and guilt over Nazi crimes.

On the other hand, guilt over the Holocaust only arises through identification with the aggressor. One cannot feel guilt over something they did not commit unless they identify with or feel represented by the perpetrator. The intense German guilt toward the Holocaust conceals an unconscious identification with the Nazis, and thus guilt over their actions. Arabs or Mexicans, for example, do not share this identification and feel no guilt over Nazi crimes, even though they too did not commit them. The very intensity with which Germans disavow Nazism points to a psychological proximity to it.

To illustrate this point, consider a phenomenon many have experienced. During the rise of ISIS and its atrocities, many Muslims were pressured to denounce ISIS to distance themselves from it. Some felt guilt and repeatedly apologized for ISIS’s actions—even though they had no more control over ISIS than a British or Chinese person. This guilt and repeated disavowal indicated an identification with the perpetrator. Those who felt no such guilt likely felt ISIS did not represent them at all.

Such identification often intensifies under external pressure—being pushed into the role of the perpetrator or repeatedly asked to disavow. This happened to some Muslims regarding ISIS, and it happens to Germans regarding Nazism. The pressure originates from within Germany itself, influenced externally by the United States.

Thus, the identification with the victim—specifically with Jews represented by “the State of Israel”—serves to repress feelings of hostility and guilt related to Nazi crimes. In turn, this repression masks the deeper identification with Nazism. This means that identification with Nazism lies at a more unconscious level than identification with Jews. No matter what, Nazis are Germans, and Jews are “the other.”

Why stress that the identification is with Jews represented exclusively by “Israel”? Because Jews who oppose “Israel” do not support the German narrative and threaten these psychological mechanisms. They are marginalized in the media and not given attention.

Jewish-American-German author Deborah Feldman writes in her book Judenfetisch (“Jewish Fetish”) that Germany “creates its Jews”—highlighting how the media amplifies individuals who discover some Jewish ancestry and suddenly adopt a fervent pro-Israel stance, even if they have no connection to Jewish teachings or matrilineal descent (a core criterion in traditional Judaism).

In other words, what matters to Germany is not the Jewish identity itself but the individual’s willingness to embrace Germany’s narrative. Germany objectifies Jews, seeing them as tools to affirm its moral narrative. Feldman explains that the German media and society exert unspoken pressure on Jews to adopt this narrative of Holocaust remembrance and support for “Israel” as a means of redeeming Germany’s past. Consequently, Jews who challenge this—like Feldman herself—are marginalized.

The German attitude seems to be: “You’re Jews, you all suffered the Holocaust, you see Israel as your homeland, and we support it for your sake. This atones for our sins and proves our courage.” According to Feldman, this replaces real Jews with artificial ones and perpetuates the destruction of Jewish identity in Germany.

This reveals how German support for “Israel” is often self-centered—a projection of internal needs and unresolved guilt, which itself is a manifestation of identification.

(On a side note, there’s another form of identification with the perpetrator—adopting their tools and replicating their crimes. This applies to Israelis who, despite their Holocaust history, practice racism and ethnic cleansing against Palestinians. In this sense, they identify with the Nazis, whom Germans now disavow.)

Projection

This is the second defense mechanism.

After “Israel’s” victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, the German newspaper Bild ran the headline: “It’s Victory! Dayan is Israel’s Rommel!”

The paper likened Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan to Erwin Rommel, one of the greatest German military commanders, known as the Desert Fox. Rommel was a general in the Wehrmacht before and during the Nazi era and later turned against Hitler. At the time, the Wehrmacht was still seen as a national military symbol, not as inherently Nazi as it is now. Thus, Rommel held positive symbolic value—as a distinguished military leader who opposed Hitler.

Rommel was a brilliant tactician who achieved victories on several fronts. Bild’s comparison of Dayan to Rommel following “Israel’s” victory in 1967 reveals an unconscious German identification with “Israel,” viewing it as an extension of German military identity. Germans projected their long-repressed desire for military victory onto “Israel,” celebrating its triumphs as if they were their own.

Not only that—Der Spiegel’s founder published an article in his magazine after the Israeli victory, writing how “Israeli soldiers crossed the battlefield like Rommel.” The article was lengthy and full of expressive, celebratory language about Israel’s military prowess and its overwhelming defeat of the Arabs. The tone conveyed that Germany, not “Israel,” had won the war.

The article also described the victory as a “Blitzsieg im Blitzkrieg”—a “lightning victory in a blitzkrieg.” The term Blitzkrieg originally described German military tactics, a word drawn straight from the German national military lexicon.

Comparing Israel’s victory to German triumphs, Dayan to Rommel, and using the term Blitzkrieg—all while Germany was providing direct military support to “Israel”—clearly illustrates the psychological projection at play. Germans unconsciously “Germanify” (make German) “Israel,” projecting their yearning for military glory onto it and experiencing vicarious pride in its victories.

Another example: Stuttgarter Zeitung wrote at the time, “The old 2,000-year-old image of the Jewish man has now been replaced with a new image: the Jew as a brilliant military strategist and brave soldier confronting death.”

Such glorification of Israeli soldiers by a militarily defeated nation further demonstrates identification and projection of German aspirations and identity onto “Israel.”

Daniel Marwecki writes in his book that Germany’s bias toward “Israel” in 1967 surpassed even that of the United States. He attributes this to widespread ignorance about Middle Eastern history and an underlying attempt to repress guilt.

The author also notes that Germany’s sympathy for “Israel” is narcissistic. Germans sympathize with an idealized image of themselves that they project onto “Israel.” This kind of projection reflects a complete inability to see the broader context of the Middle Eastern conflict.

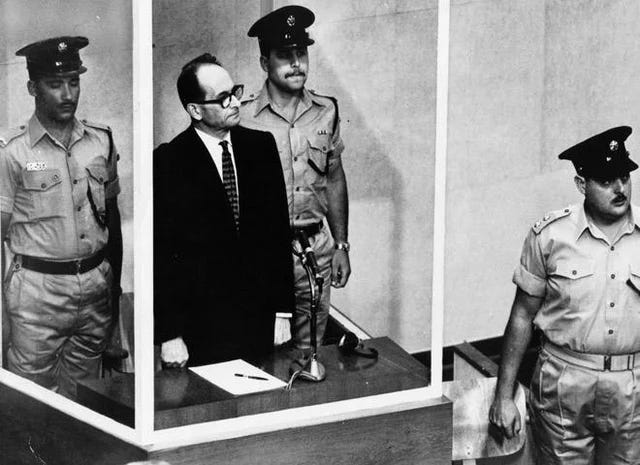

The Eichmann Trial

One of the key events in German–Israeli relations was the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a major architect of the Holocaust. The Israeli Mossad kidnapped him from Argentina and brought him to “Israel,” where he was tried publicly and executed in 1962. The trial drew global attention and marked the first time the Holocaust was publicly addressed; before then, it had remained a private issue for survivors.

German Foreign Ministry archives contain numerous documents showing concern that the trial threatened Germany’s international image and interests. The German Chancellor at the time, Konrad Adenauer, was prepared to cancel German aid to “Israel” unless the trial clearly separated Nazi Germany from postwar Germany.

Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion personally oversaw the trial to ensure this separation was made. He even delivered a speech absolving the German people from Nazi crimes (a stance that contradicts today’s dominant consensus). A German observer attended the trial, documented the proceedings, and confirmed that this agreement was honored.

During the trial, however, Arab countries were framed as the heirs of Nazism. Figures like the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, were blamed for contributing to the Holocaust. In effect, Israel downplayed the connection between modern Germany and Nazism while amplifying an Arab connection to it. “Germany was denazified, and Arab states were nazified,” as Daniel Marwecki puts it.

In this way, Arabs became, in Israel’s narrative, more aligned with Hitler than present-day Germans. This narrative shift was part of the unspoken bargain: in exchange for German aid, “Israel” helped rehabilitate Germany’s global image. Associating Arabs with Nazism also helped Israel justify its policies and presence in the Middle East.

This marked the beginning of projecting Nazism onto Arabs. That projection has persisted—branding leaders from Gamal Abdel Nasser (“Hitler of the Nile”) to Yasser Arafat (“Hitler of Beirut”) as modern-day Nazis. The broader opposition to “Israel” is thus regularly portrayed as rooted in antisemitism.

The German observer at Eichmann’s trial gave a disturbing final speech: “What strikes the European visitor to Israel is seeing this new, distinguished generation of Israeli youth. They are tall, with blue eyes and often blond hair… the descendants of German Jews represent a new kind of Jew.”

This overtly racist comment praised Jewish Israelis for resembling Aryan Germans—a striking example of unconscious projection. Germans were celebrating themselves in the image of “Israel.” (Marwecki cites this as a case of how German antisemitism can manifest in pro-Israel sentiment.)

Projection, in psychological terms, is the unconscious transfer of one’s own repressed traits—whether shameful or desirable—onto someone else. This often includes accusing others of the very things one cannot accept in oneself.

Projection also plays a compensatory role: by assigning admired traits to another, one facilitates emotional identification, especially when repressed hostility prevents a more honest relationship.

Today, Germans project their longing for military pride onto Israelis, while projecting their own Nazi past, antisemitism, and genocidal legacy onto Arabs. In this way, Arabs—not Germans—are made to bear the legacy of Nazism.

For example, an article in Der Freitag portrayed Arabs as seeking to exterminate Jews, quoting a dubious line allegedly spoken by al-Husseini before Israel’s founding: “Those Zionist invaders—we will slaughter them to the last man. We don’t want development or prosperity (brought by Jewish immigration).”

Tracing the origins of this quote leads only to a sensationalist 1947 article in the New York Post. There’s no record of this quote in Arabic, even though it was supposedly spoken in Arabic. Despite diligent research, no source reproduces this statement in its original language.

Furthermore, the idea of genocide against Jews is entirely foreign to Arab and Islamic ideology, which contains many principles that oppose such actions. No Islamic jurist has ever advocated racial extermination of Jews or anyone else. There is no ideological, cultural, or historical basis for such an idea—it is alien, out of context.

So who did think about racial extermination, and who wanted to eliminate Jews to the last man? The Germans. Germans are now attributing to Arabs what they themselves intended to do. They fabricate or spread unverified quotes attributed to Arabs.

Another example: a Welt podcast was titled “The slogan ‘Free Palestine’ is the modern version of ‘Heil Hitler.’”

German media is filled with similar examples, projecting Nazism onto Arabs and reducing all opposition to “Israel” to antisemitism. As we explained in the previous article, The Shame of the Holocaust: Dissecting Germany’s Position on Israel, antisemitism is a phenomenon rooted in European history. Applying the term to other peoples with vastly different historical contexts is inaccurate.

“Israel,” as we mentioned, constantly promotes the idea that Arabs are the heirs to the Nazis. In 2015, Netanyahu even claimed that Hitler didn’t originally intend to kill the Jews, but was convinced to do so by the Grand Mufti al-Husseini. Netanyahu made Arabs more Nazi than Hitler himself. This lie blatantly contradicts the most basic tenets of German memory culture and was officially denied by Germany.

It is crucial to understand that these psychological defense mechanisms (by definition unconscious) describe individual or collective psychologies—not political actors. Governments understand history and politics. When they engage in such projections, it is not unconscious defense—it is calculated deception for political gain. When governments project, they manipulate the public to steer it in a desired direction.

Thus, Germans see the Middle East conflict as follows: “Israel” is Germany, Arabs are the Nazis, and Germany is once again proudly fighting Nazism. This has no connection to the real context of the Middle East but reflects Germany’s fractured identity and attempts at reinvention after the war.

Today, as Germany aligns itself against the Palestinian narrative, many Palestinians in Germany say they feel they are being punished for the Holocaust—accused of antisemitism and of wanting to exterminate Jews, traits that historically belonged to German society. Palestinians punished for committing the Holocaust—by Germans themselves. This is one of the clearest signs of projection.

Reaction Formation

This is the third defense mechanism, which we previously addressed in the article The Shame of the Holocaust, and will now explain more fully to complete the analysis. Reaction formation occurs when a person harbors a shameful or socially condemned feeling or impulse and, unconsciously, adopts the opposite behavior in an exaggerated manner to repress that inner feeling. Sometimes, a person may even fulfill the repressed desire through the opposite behavior, thereby avoiding its disturbing implications.

Some everyday examples include: a young man who speaks ill of a girl he’s unconsciously attracted to; or an employee who constantly gossips about a colleague promoted over her, even though she secretly admires that colleague’s work ethic; or someone overly kind to a neighbor he deeply dislikes. If these behaviors are unconscious, they are manifestations of reaction formation.

Another example: a man who advocates feminism and women’s rights outwardly, yet ends up infantilizing women by exempting them from responsibility or applying biased favoritism. This patronizing behavior implies a hidden belief that women are less competent—an idea he seeks unconsciously to repress, but which emerges through his patronizing actions. In doing so, he fulfills his unconscious bias in a socially acceptable form.

Now, returning to the Germans: a segment of German society still harbors unconscious resentment or disdain toward Jews. Because expressing this is ethically forbidden, they engage in exaggerated support for Israeli policies, even to the extent of shielding Israelis from accountability. This infantilizing support implies that Jews are not seen as responsible adults, thus revealing a subtle form of underlying contempt.

This stands in contrast to those who rationally denounce the Holocaust, sympathize with its victims, and support them without blind allegiance—treating them as moral equals capable of responsibility and growth.

Antisemitism has deep roots in Europe, dating back over a thousand years. It manifests in the persistent rejection, marginalization, and persecution of Jews throughout European history, reaching its apex in Nazi Germany. It is embedded in Europe’s historical memory and cannot simply vanish overnight.

It is inevitable that hatred of Jews and a desire to rid Europe of them still exist among some Germans. These feelings are repressed due to moral condemnation, and reaction formation emerges: the overcompensating, uncritical support for “Israel.” At a deeper level, this aims to ensure that Jews remain elsewhere—most importantly, outside Europe.

The actual outcome of intense European support for “Israel” is a reduced Jewish presence in Europe and avoidance of confronting the “Jewish question” once again. Europe thereby fulfills a centuries-old desire—removing Jews—without guilt or accusations of antisemitism. As previously mentioned, social phenomena that persist for centuries do not disappear suddenly.

Daniel Marwecki quotes historian Zack-Krakotzkin of Ben-Gurion University: “Paradoxically, the expulsion of Jews from Europe enabled their reintegration into it.” Historically, this is true: Europe—and Germany specifically—could only integrate the remaining Jews after the majority were expelled to Palestine. Refer again to the mechanism of reaction formation.

A report by Germany’s Independent Expert Panel on Contemporary Antisemitism, published by the Interior Ministry, includes a striking quote from an Israeli psychoanalyst: “The Germans will never forgive us for Auschwitz.” The implication is that present-day Germans may unconsciously resent Jews not despite the Holocaust—but because of it.

The Holocaust imposed enormous guilt and shattered the German self-image. This rupture is the root of the psychological defenses discussed throughout this article.

When migrants or foreign students arrive in Germany, they are often surprised to discover that in language courses, Germans almost never use the term Volk (“the people”) to refer to themselves. Instead, they use Bevölkerung (“the population”), a more neutral term that includes all residents of Germany. The word Volk is largely avoided.

This avoidance is deliberate. Volk carries strong associations with Nazi ideology and racial nationalism. For many Germans, simply using the word evokes feelings of racism or fascism. Could there be a clearer indicator of a fractured collective identity than a society that sees the word “people” as inherently suspect? (The term Volk is still used by the far-right in explicitly racist contexts, which only deepens the stigma.)

If we were to distill this article into a single core insight, it would be this: Germany’s current stance on Palestine and “Israel”—and its highly developed culture of Holocaust remembrance—presents itself as a moral position.

But beneath the surface, it functions as a psychological and political strategy rooted in projection, repression, and unresolved historical trauma. It serves to stabilize Germany’s internal contradictions, redirect collective guilt, and reinforce its postwar alignment with the United States.

It’s essential to emphasize that psychological defense mechanisms are, by nature, individual. They do not apply universally. Each of the mechanisms described—repression, projection, reaction formation—can be observed in a broad segment of German society, but not in every individual. The transformation of these inner psychic processes into collective behaviors and political culture is itself a phenomenon worth deeper analysis.