Memory of Genocide in Srebrenica, Rwanda, and Gaza: How Do Survivors Remember Their Tragedies?

Documentation is not merely the archiving of events—it is, in the context of genocide, the cornerstone of accountability and prevention. In 1946, the United Nations defined genocide as the killing of members of a national, religious, or ethnic group; the infliction of serious bodily or mental harm; the imposition of living conditions intended to bring about the group's destruction in whole or in part; measures to prevent births; and the forcible transfer of children to another group.

Before and after that definition, the world has witnessed horrific massacres targeting entire populations. Yet, the mechanisms of documentation and international response have varied from one tragedy to another. Today, with the rise of digital media and advanced methods of evidence collection, documentation has become more critical than ever in exposing violations and ensuring justice. But a profound question remains: how do we chronicle catastrophe? And how do we preserve the memory of its victims?

Gaza: A Genocide in Real Time, Broadcast to the World

Gaza is the first genocide in history to unfold live before the eyes of the world, transmitted through the lens of modern communication technology. As images often convey the deepest sense of tragedy, the photobook "Gaza… I Spy" captures the lives of Gaza’s children under the shadow of annihilation, through 200 vivid images accompanied by poetry and prose.

Media coverage has also been shaped by a few brave Palestinian voices who found themselves alone in a desolate media landscape. Journalist Wael Dahdouh received the 2024 Courage in Journalism Award from Reporters Without Borders. Photojournalist Samar Abu Elouf was honored by Amateur Photographer magazine, while 20-something journalist and content creator Bisan Owda won an International Emmy for Outstanding Hard News Story for her documentary "I Am Bisan from Gaza... and I Am Still Alive."

In cinema, the documentary From Zero Distance, directed by Rashid Masharawi, was nominated for Best International Feature at the Oscars. The film comprises 22 short pieces shot by Palestinians inside Gaza during the war—each created under impossible conditions of siege and bombardment.

On the legal front, nearly a year into the war, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, charging them with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

In January 2024, South Africa filed a formal case at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide—a move later supported by several other countries. Hundreds of meticulously documented human rights and medical reports from respected international organizations now form a vital part of the living archive of aggression.

In a moving symbolic gesture, Irish orthopedic specialist Mary Evers has memorialized Gaza’s martyrs by embroidering their names onto cloth using the colors of the Palestinian flag—black for men, red for women, and green for children.

Artistically and culturally, Gaza’s genocide has appeared in art galleries and traveling exhibitions worldwide. Yet no permanent museum has been dedicated to it. The Nakba of 1948 remains the most represented tragedy in Palestinian museums, both in the West Bank and at the Palestine Museum in Connecticut, USA.

In the literary world, two English-language books published in 2024 document the unfolding genocide in Gaza. The first, Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide, is by former Palestinian Culture Minister Atef Abu Saif. Trapped in Gaza during a cultural heritage event, he recorded nearly three months of personal observations and psychological shifts under relentless bombardment.

The second book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, is by Egyptian-Canadian journalist and award-winning novelist Omar El Akkad, who famously won the Scotiabank Giller Prize for What Strange Paradise. The title stems from a viral post El Akkad shared on X, viewed over ten million times:

"One day, when it is safe, when there is no cost to naming things as they are, when it’s too late to hold anyone accountable—everyone will have always been against this."

In Arabic, the poetry anthology Gaza, Is There Life Before Death? features the voices of 26 poets from Gaza and the diaspora, offering a living, evolving record of tragedy. Soon to be released by Dar Al-Adab is Memory of Loss: Gaza’s Testimonies of Genocide by Syrian novelist Samar Yazbek—a literary act of remembrance and resistance.

Rwanda: A Landscape of Visual Memory

In 1994, Rwanda witnessed the deadliest genocide in modern African history. Over a span of 100 days, an estimated 800,000 people—mostly Tutsis—were slaughtered by Hutu extremists.

Today, Rwanda and the United Nations commemorate the genocide each year on April 7. Official ceremonies and candlelight vigils are held, with survivor testimonies shared in audio and visual form.

These personal narratives have played a pivotal role in international prosecutions, notably at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), and in local “Gacaca” courts that allowed victims and their families to confront perpetrators within their own communities—fostering restorative justice and national reconciliation.

Such testimonies are now preserved in public archives, media platforms, and documentaries that help ensure global remembrance of the atrocity.

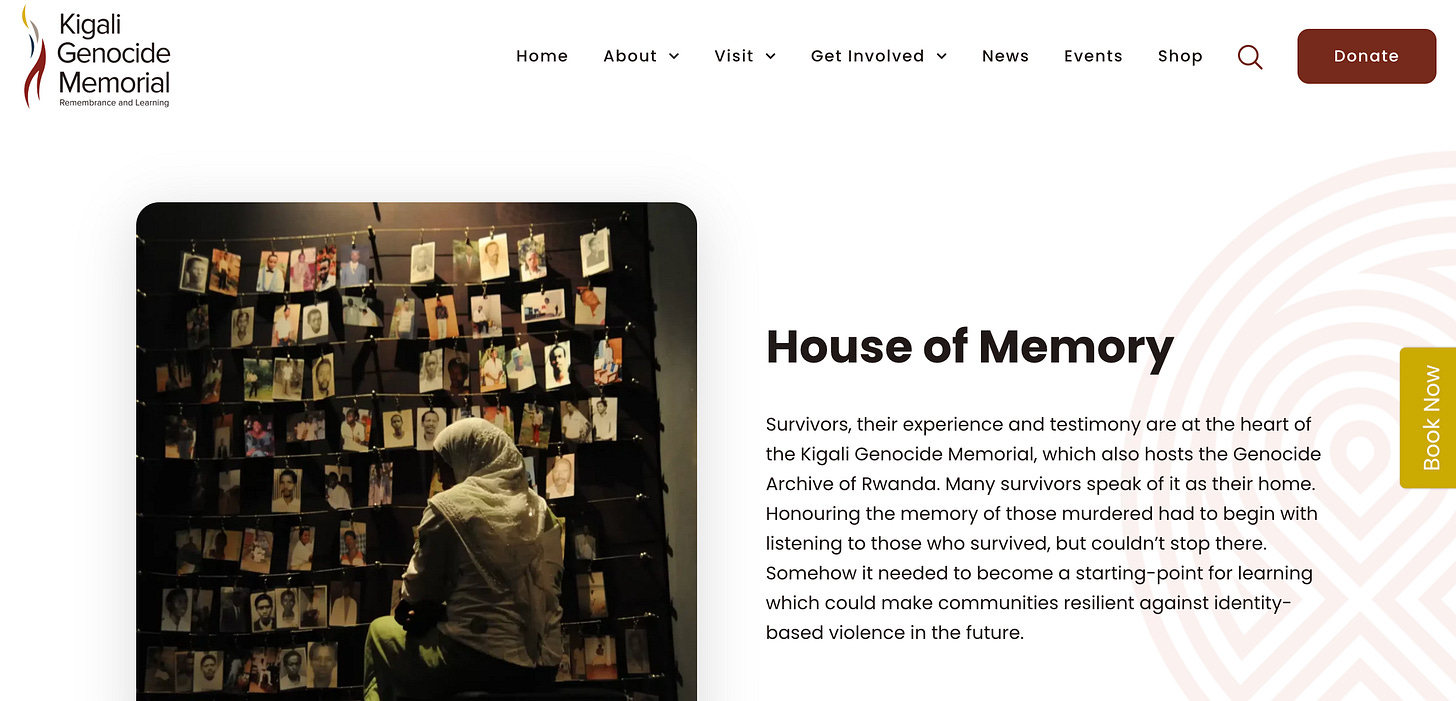

Rwanda is dotted with memorials commemorating the genocide. Chief among them is the Kigali Genocide Memorial, situated on Gisozi Hill, where a quarter-million victims are buried. It features images, artifacts, survivor stories, and physical evidence of the horrors—clothes, letters, personal belongings.

Churches that became massacre sites—like Nyamata, Murambi, and Bisesero—now serve as chilling memorials, displaying skulls, bones, and garments. In 2023, UNESCO added these four sites to its World Heritage list, recognizing them as tangible, direct witnesses to genocide and its enduring scars.

Rwanda also integrates genocide education into its school curriculum to inform future generations and prevent recurrence. Public awareness programs and workshops promote peace and reconciliation, and denial of the genocide is criminalized both domestically and in several European countries.

Art and cinema have played crucial roles in globalizing Rwanda’s story. The Girl Who Smiled Beads, a memoir by genocide survivor Clemantine Wamariya, co-authored with Elizabeth Weil, has been translated into Arabic and stands out among literary testimonies. Numerous other works remain untranslated.

Films like Hotel Rwanda, Sometimes in April starring Idris Elba, and Kinyarwanda—a love story between a Hutu and a Tutsi—have all etched Rwanda’s tragedy into the global cinematic consciousness.

Srebrenica: A Wound in the Heart of Europe

Each July 11, the world commemorates the Srebrenica genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina—an atrocity the United Nations officially recognizes as genocide. It took twelve years for the 1995 massacre to gain that legal designation.

A special tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), was convened to prosecute war crimes in Bosnia. Several Serbian military leaders and soldiers were convicted. Yet, genocide denial remains legal in Bosnia, unlike in countries such as Germany, France, Poland, and Austria, where Holocaust denial is criminalized.

Every year, the “Marš Mira” peace march retraces the “path of death” taken by fleeing civilians between July 8 and 10. Some survived; others were killed. The event concludes with a memorial ceremony at the mass grave site in Potočari.

The following day, newly recovered remains are buried in a mass funeral attended by religious and political leaders, including Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in recent years.

The Srebrenica Flower—a white bloom with eleven petals representing July 11 and a green center symbolizing hope and healing—has become the genocide’s emblem.

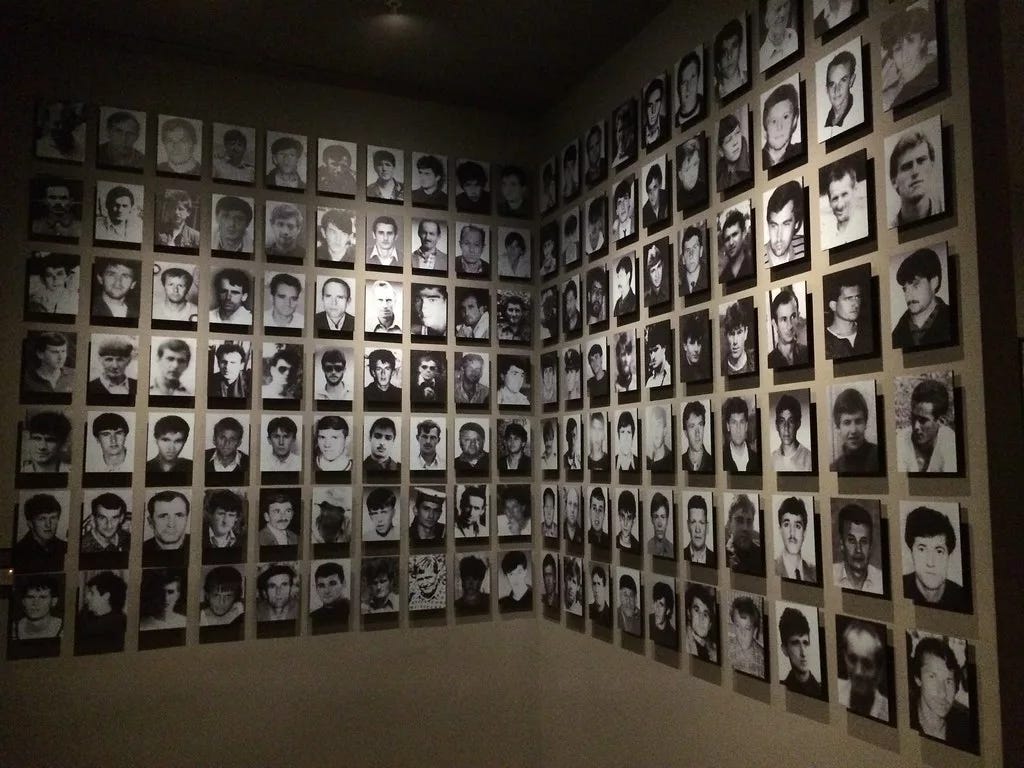

In the years following the massacre, several museums were established to document the genocide. The Potočari Memorial Center, once a UN military base, opened in 2012 with an exhibition titled Srebrenica: Genocide at the Heart of Europe. The exhibit includes photos, testimonies, multimedia presentations, and human remains from mass graves.

In Sarajevo, the War Childhood Museum captures the impact of siege and starvation on children through their belongings and stories. A book by the same name documents these memories.

Bosnian author Hasan Hasanović, a survivor, has penned two books: Surviving Srebrenica and Voices from Srebrenica. Another book—based on a research trip through Bosnia’s war memory—is expected soon and was recently commended by the 2024 Ibn Battuta Prize jury.

Numerous films have depicted the Bosnian tragedy, though most focus on rape camps rather than the genocide itself. Twice Born, starring Penélope Cruz, is among the most notable, contributing to the cinematic remembrance of the war.

The BBC’s Srebrenica: A Cry from the Grave stands out for its survivor testimonies and harrowing escape stories. Al Jazeera Documentary’s The Bone Collector follows a man who searches hillsides for human remains, delivering them to the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) investigation teams.

Genocide stands as a chilling reminder of what humanity is capable of when justice and moral order collapse. These crimes, though decades past, remain etched in collective memory—summoning our vigilance, demanding accountability, and compelling us to prevent their repetition.