The young Algerian revolutionary Mohamed Boudia believed deeply in his people’s right to self‑determination, free from French colonial rule. He joined the resistance at an early age and led the Algerian National Liberation Front’s Paris cell, which carried out numerous operations against colonial interests. When Algeria finally won its independence, he returned to his first love: theater.

Algeria was liberated, but he did not lay down his arms. Boudia was an internationalist revolutionary committed to struggles for liberation chief among them what he viewed as humanity’s central cause: Palestine. He decided to join the Palestinian struggle with his weapon, his pen, and his exceptional skills in planning clandestine operations.

His mastery of theater helped him craft elaborate disguises to evade Israeli intelligence and the French security services, which pursued him for years. Eventually, Mossad succeeded in assassinating him as part of Operation “Wrath of God” on the morning of June 28, 1973, in Paris. Yet despite his assassination, his legacy endures in the causes of Palestine, Algeria, and global liberation movements.

Mohamed Boudia: The Revolutionary Maker

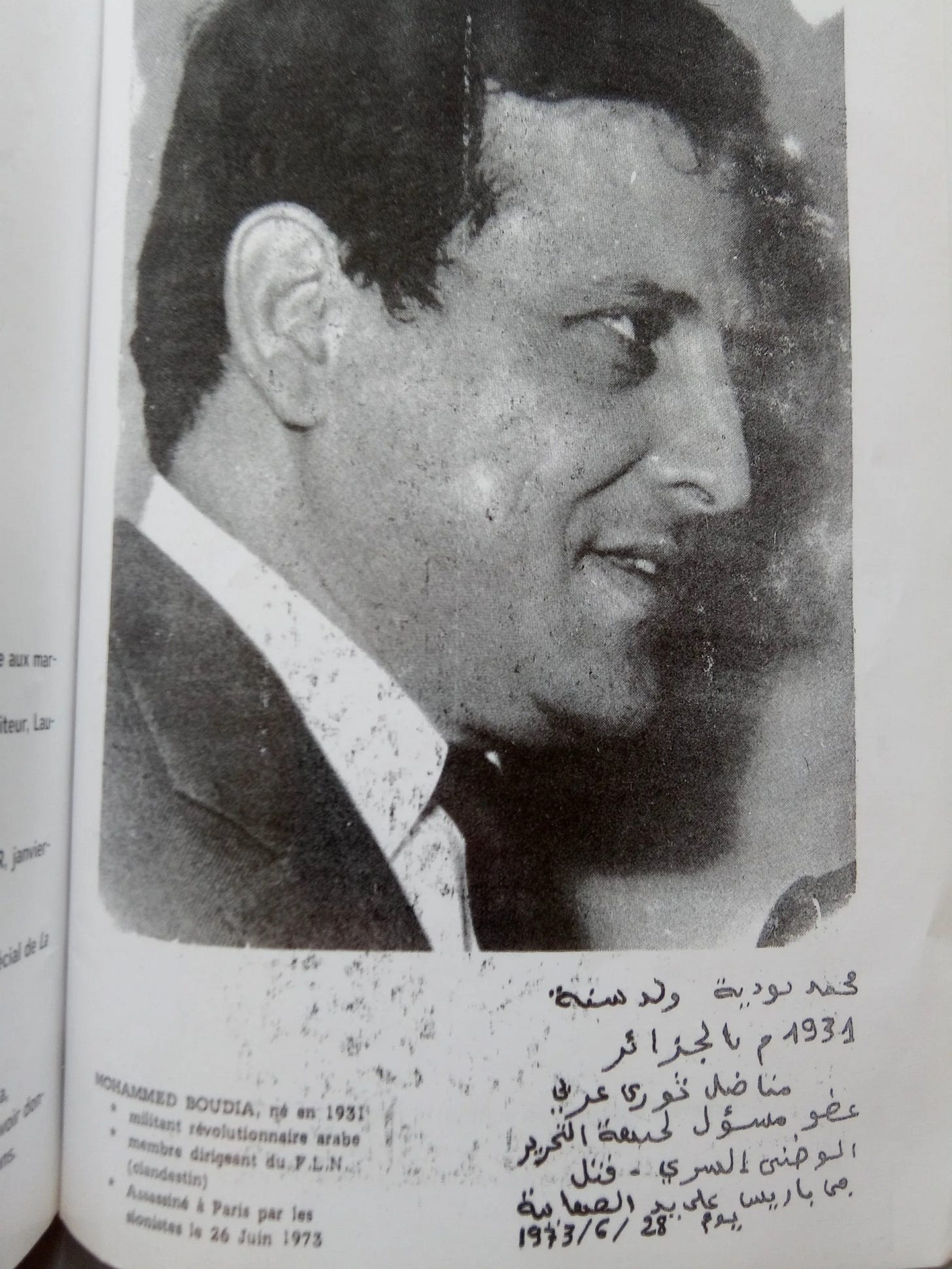

On February 24, 1932, in the Bab El Jedid quarter of the upper Casbah of Algiers, a child named Mohamed was born into the Boudia family. He grew up in the historic streets and schools of the Casbah and joined the Algerian Muslim Scouts.

During his school years, Boudia developed a passion for theater. At 22, he enrolled in the Regional Center for Dramatic Arts to hone his talent. He possessed a commanding eloquence, strong powers of persuasion, and notable talent in expression and writing.

His theatrical work in Algeria did not last long. He was conscripted into military service first in Algiers and later in Dijon, France under the compulsory draft imposed on Algerians since 1912. But in France, fate led him to meet an Algerian theater troupe in Dijon and, through them, Algerians active in the struggle for independence from a colonial power that had violated land, dignity, and wealth.

Boudia wanted to serve his country through the art he loved. He wrote plays celebrating resistance and denouncing occupation, works intended to stir people to revolt against colonial repression. He had lived through colonial brutality and was deeply marked by the massacres of May 8, 1945.

He believed passionately in the role of culture and theater in liberating his country. He used his pen and voice to lay the groundwork for a “theater of resistance.” For him, culture was synonymous with freedom, and theater an extension of the national struggle. Once independence was achieved, he believed theater should become a social and political instrument of liberation.

But the outbreak of the armed Algerian Revolution in late 1954 drew him into the clandestine ranks of the National Liberation Front (FLN), which had decided to bring the war to France. He quickly became head of the FLN’s Paris cell, which oversaw several operations in France between 1957 and 1958, including the August 25, 1958 bombing of oil pipelines near Marseille.

A few weeks later, French authorities arrested Boudia and sentenced him to 20 years of hard labor. However, on September 10, 1961, he escaped from Angers prison with the help of French anti‑colonial activists and fled to newly independent Tunisia.

The Beginning of a New Struggle

Months after his escape, Algeria gained independence. But the internationalist revolutionary Mohamed Boudia believed liberation would remain incomplete until all occupied lands were freed especially Palestine, which he saw as the foremost cause after its occupation by Israel with Western support.

Boudia’s connection to the Palestinian cause began in Cuba, where he met Wadie Haddad, also known as Abu Hani, the head of external operations for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). That meeting strengthened his conviction that his experience should be placed at the service of the Palestinian struggle.

This period coincided with the Arab defeat of June 1967, when Israel waged a six‑day war against Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, leading to vast territorial losses and the destruction of most Arab military assets.

Boudia wrote extensively on Palestine, driven by the fervor he carried from his years with the FLN and from political theater. He leveraged his wide network of artists, intellectuals, and political figures across Europe, the Arab world, and Latin America to promote awareness of the Palestinian cause.

Armed Struggle

After the Arab defeat, many revolutionaries shifted to armed resistance, expanding operations against Israeli targets abroad. Boudia embraced this path, convinced that rights are not granted but seized by force.

Wadie Haddad led an international coalition of armed groups known as the “External Operations Department.” In the early 1970s, Boudia was tasked with leading PFLP operations in Europe, following a short stay at Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow.

Boudia by then operating under the nom de guerre Abu Diya became the mastermind behind most PFLP operations and later Black September operations in Europe. These actions targeted Israeli interests in response to Israeli violence, international indifference, and to awaken the world’s conscience regarding Palestine.

He coordinated with several revolutionary groups, including the Japanese Red Army, Germany’s Baader‑Meinhof Group, Italy’s Red Brigades, and Spain’s ETA. He also recruited youth in support of the Palestinian struggle.

Among his operations was an attempt to send three East German women to Jerusalem to bomb Israeli targets, a plot that was uncovered. He also oversaw the bombing of the Shono Center in Austria, which processed Soviet Jewish migrants heading to Israel.

Boudia also supervised the bombing of Israeli warehouses and a petroleum refinery in Rotterdam, as well as the May 8, 1972 hijacking of an Israeli airliner at Lod Airport (Ben Gurion Airport), during which both militants and Israeli soldiers were killed in a failed rescue attempt.

He additionally oversaw the Japanese Red Army operation led by Kozo Okamoto targeting Israeli aircraft at Lod Airport, killing 26 people and injuring at least 80. He planned the August 5, 1972 explosion of a petroleum pipeline between Italy and Austria near Trieste, destroying nearly 250,000 tons of oil.

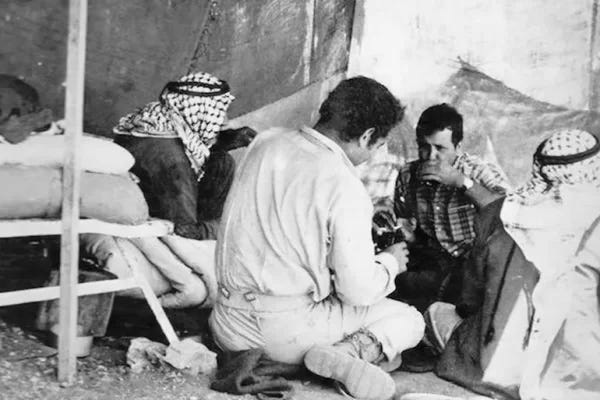

That same year, he hosted the Palestinian commandos responsible for the Munich operation, helping hide and eventually move them. The operation involved the capture of 11 Israeli athletes during the Munich Olympics and demands for the release of 236 Palestinian prisoners. The German security assault resulted in the death of all the hostages.

“The Man of 100 Faces”

Boudia supervised all these operations without leaving a trace. Reports from Mossad and Western intelligence services, including French and Swiss, indicated they were sure he was involved in planning attacks on Israeli interests and Mossad personnel, but they lacked evidence. He continued to work in theater openly and without raising suspicion.

According to a Swiss intelligence report, Boudia traveled through European capitals using numerous aliases and forged identities such as “Bertan Pierre,” “Bertan Roland,” “Boyer Maurice Andres,” “Rodrigue,” “Robert,” “Roger,” “Bethanchan,” as well as Arabic names like “Saeed Ben Ahmed,” “Abu Khalil,” and “Abu Khaled.”

He frequently changed residences in Paris to avoid leaving any trail that could lead those searching for the mastermind behind Palestinian operations in Europe—a skill he had refined during his time in the Algerian resistance and at Patrice Lumumba University.

The End of a Hero

For a long time, Mossad and Western intelligence believed multiple people were behind the operations targeting Israeli interests in Europe. Eventually, after exhaustive pursuit, they concluded it was the work of one man: Mohamed Boudia.

Mossad did not wait for definitive evidence. It decided to eliminate the Algerian revolutionary at the first opportunity as part of Operation “Wrath of God,” authorized by then‑Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and executed by the Kidon unit led by agent Michael Harari.

Their task was difficult Boudia had no stable residence and no consistent identity.

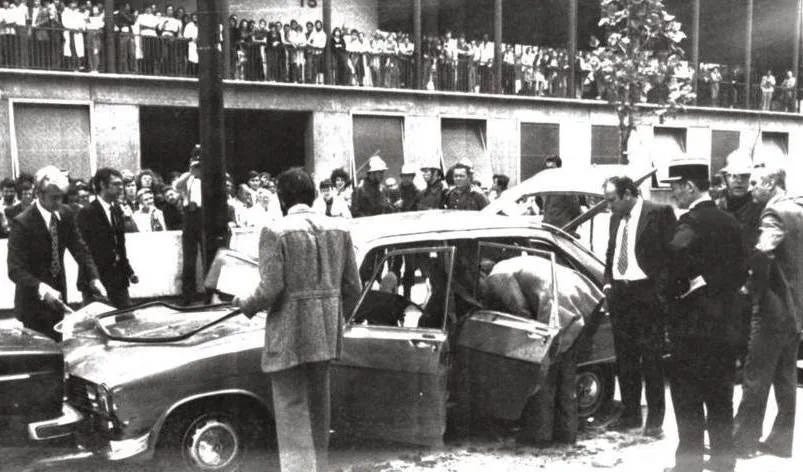

On the morning of June 28, 1973, Boudia prepared to leave an apartment he frequented in Paris’s Fifth District, dressed in his theatrical attire. He walked to his blue Renault 16 parked on Rue Fossés‑Saint‑Bernard. As he opened the door and touched the driver’s seat, a small explosive device hidden beneath it detonated.

He was killed instantly at 41, after spending more than half his life fighting for Algeria, Palestine, and global liberation movements.

Mossad succeeded in assassinating Mohamed Boudia that day, with assistance from French security elements. But it failed to halt the struggle for a just cause embraced by millions. After the martyrdom of the internationalist revolutionary, countless others carried the torch, and such resistance will not end until the Israeli occupation comes to an end.