In the first half of the twentieth century, the Hejaz witnessed profound transformations, most notably the unification of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932 under the leadership of Abdulaziz Al Saud, following years of conflict with local forces and the Ottoman Empire.

Economically, the region suffered from a lack of resources prior to the discovery of oil, making the annual Hajj season its primary source of income.

Amidst this backdrop, Muhammad Asad embarked on the Hajj in 1927—not as a typical pilgrim, but as a European Jewish intellectual who had recently embraced Islam. His pilgrimage became a symbol of his spiritual and intellectual rebirth.

Asad chronicled this transformative journey in his seminal book The Road to Mecca, blending awe and admiration with criticism and sorrow over the disorderly arrangements, economic exploitation, and at times superficial religiosity he encountered.

A Restless Soul: What Led Him to Hajj?

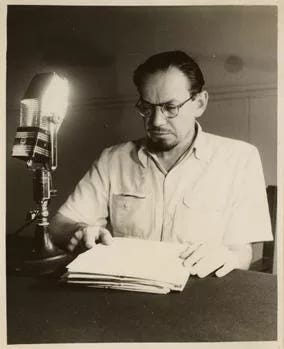

Born Leopold Weiss in 1900 in the city of Lviv—then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and now located in Ukraine—Asad came from a distinguished Jewish family, several of whom were rabbis. He received a traditional religious education and, by age 13, was fluent in Hebrew and Aramaic, a linguistic foundation that later eased his study of Arabic.

However, as his engagement with the Talmud deepened, Asad grew increasingly disillusioned with Judaism, particularly the notion of a God devoted to one chosen people. Disappointed with Judaism, he explored Christianity, yet found its concepts of soul, body, and salvation equally unconvincing. Disenchanted with all prevailing religious doctrines, Asad came to see himself as an agnostic.

After World War I, Asad enrolled at the University of Vienna to study philosophy and art but soon dropped out, disillusioned with academic life. He pursued journalism instead and moved to Berlin, where he joined the American news agency United Telegraph, launching his career in media.

He later received an invitation from his uncle Dorian—a psychoanalyst and student of Freud residing in Jerusalem—who, ostracized for opposing Zionism, sought companionship in his nephew. Asad visited Jerusalem in 1922, a pivotal encounter that altered his view of Islam.

Contrary to his European perceptions, he discovered a faith detached from violence and rich in spiritual depth.

That same year, he became a correspondent for a German newspaper and met several Zionist leaders, yet he firmly rejected Jewish settlement in Palestine as immoral and sympathized with the Arabs.

Following an 18-month stay in the Middle East, Asad returned to Germany and published a book in German titled Unromantisches Morgenland (The Unromantic Orient), critiquing Zionism and discussing Egyptian independence. He then embarked on a new journey through Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey, and Central Asia.

During his travels, Asad was profoundly influenced by the everyday lives of Muslims and the sense of purpose and inner peace their faith provided. He became enamored with Arab society, seeing in it a cohesive worldview starkly different from European modernity. He critically reflected on the contrasts between Islamic values and Western ideals, dissecting fundamental differences in their perceptions of existence, meaning, and purpose.

He mastered Arabic and met numerous influential figures, including Sheikh Mustafa al-Maraghi, who would later become Grand Imam of Al-Azhar. His encounters in Palestine and Syria left a lasting impact, and a dialogue with a local Afghan ruler in Herat further deepened his understanding and appreciation of Islam.

Returning to Germany in 1926 at age 26, Asad was already a well-known journalist. He married the German painter Elsa, who shared his interest in Islam. In his memoirs, Asad recounts a decisive moment that led to his conversion: while riding the upper-class metro in Berlin, he and Elsa observed the passengers—well-dressed, affluent, yet visibly burdened with existential gloom.

He turned to his wife, an artist skilled in reading facial expressions, and asked, “What do you see in their faces?” She replied, “They look as though they’re suffering in hell.”

Perplexed by this paradox of visible affluence and palpable despair, Asad returned home and found a German translation of the Qur’an on his desk. As he moved to close it, his eyes fell upon a short surah—Surat At-Takathur—which struck him as a direct commentary on what he had just witnessed in the metro.

Handing the book to Elsa, he said, “Read this... isn’t it an answer to what we saw?” That moment sparked a profound conviction in Asad: the Qur’an was indeed divinely inspired. He later wrote:

“I was certain that these verses were not the product of a man, however wise, who lived thirteen centuries ago in a remote corner of Arabia. How could he have foreseen this psychological torment, this spiritual misery, this hell of the twentieth century?” (The Road to Mecca, p. 370)

The following day, Asad visited a mosque in Berlin, declared the shahada before the community’s imam, and formally embraced Islam. When he revealed that his name meant “Leopold” or “lion,” the imam suggested he adopt the name “Muhammad Asad”—a name he kept for the rest of his life.

From the Heart of Europe to Mecca

Shortly after converting, Asad left Europe in 1927, not merely to change his geography, but to embark on a cultural and spiritual metamorphosis. With Elsa and their son, he set off for Mecca to perform the Hajj. On the Mediterranean voyage, he often left his luxury cabin to sit among the lower-deck travelers.

Onboard, he befriended a group of Yemeni pilgrims returning from Marseille, particularly a calm and composed man who showed great warmth upon learning of Asad’s conversion. They spent long hours on deck discussing life in Yemen.

One evening, Asad encountered a Yemeni man stricken with fever who had been neglected by the ship’s doctor. Asad gave him quinine tablets, earning the deep gratitude of the Yemeni pilgrims. Later, they presented him with a monetary gift in appreciation—a token of brotherhood and affection, which he humbly accepted.

When the ship reached Suez and then Rabigh, Asad observed North African pilgrims donning their ihram. Finally, as they docked in Jeddah, Asad was captivated by the sight of pilgrims dressed in white, chanting fervently, “Labbayka Allahumma Labbayk.” For him and Elsa, it was the culmination of a long spiritual quest.

Asad admired Jeddah’s architecture—its carefully polished facades, finely crafted wooden windows, and veiled balconies that protected household privacy while offering street views. The city’s white minarets added a spiritual ambiance to its skyline.

He was also enchanted by Jeddah’s vibrant markets, where Eastern cities converged under shaded roofs. The scent of grilled meat wafted from open kitchens, and shops brimmed with goods from both Europe and the East.

Jeddah’s cosmopolitan air, teeming with diverse races and cultures, impressed Asad. As the only Hejazi city then open to non-Muslim residents, its streets featured European signs, foreign attire, and international flags.

Asad soon left for Mecca by camel in a caravan. Along the way, he encountered pilgrims, Bedouins, camels, donkeys, and modern cars that frightened the animals. The journey resounded with chants, songs praising the Prophet, and celebratory joy.

In the Embrace of Mecca and Medina

Though a law required new Muslims to stay in Jeddah for a year before entering Mecca, Asad had made prior arrangements with a renowned mutawwif, Hassan Abid. Amid the crowds, a voice suddenly called, “Where are Hassan Abid’s pilgrims?” A young man emerged, sent by Abid, to guide them home.

He found Meccan homes similar to those in Jeddah but built of heavier stone, with narrower streets and harsher heat. The city swelled with pilgrims, and water carriers roamed freely, distributing refreshments.

After a lavish breakfast, the young guide led Asad to the Grand Mosque. They passed through bustling streets lined with butchers, vegetable vendors, and colorful clothing shops selling goods from across the Islamic world.

For the first time, Asad laid eyes on the Kaaba, nestled in the mosque’s sunken courtyard. Unlike the ornate mosques of North Africa, Jerusalem, Istanbul, and Iran, the Kaaba's stark simplicity struck him with awe. Its minimalism embodied tawhid—the unity of God—and symbolized the shedding of ego.

Within the alleys and markets of the Haram, Asad experienced a rich cultural and spiritual immersion. He met Indian pilgrims who encouraged him to visit India and was moved by the collective warmth and shared faith that transcended all differences.

After nine days in Mecca, Elsa fell ill due to the heat and dietary changes. Her condition rapidly deteriorated, and she died of an undiagnosed illness that Syrian doctors in Mecca failed to treat.

Grief-stricken, Asad buried her in Mecca’s cemetery, marking her grave with a simple, uninscribed stone. Upon hearing of her death, King Abdulaziz summoned Asad, initiating a lasting friendship.

Asad then visited Medina, which he called his true home. He described its serene streets, vibrant markets, and the Prophet’s Mosque with its five minarets, the iconic green dome, and the nearby Mount Uhud.

He felt a profound connection to the Prophet Muhammad and marveled at how Muslims expressed unmatched love for a man who lived over 1,300 years ago. He wrote:

“Over more than thirteen centuries, love has accumulated here, such that all faces, all gestures, all movements acquire a kind of familial resemblance. All differences of appearance melt into a singular harmony.” (The Road to Mecca, p. 299)

Asad’s Observations

Asad grew close to King Abdulaziz, advising him on media and political affairs. While living in Medina, he was dispatched on a reconnaissance mission to Kuwait to investigate the flow of arms and funds to Faisal al-Duwaish, a rebel against Saudi rule.

He spent nearly six years traveling across the Hejaz, living with Bedouins, sleeping under the stars, and surviving a near-fatal desert ordeal when he lost his way and almost died of thirst.

He recounted the grueling conditions aboard ships carrying North African and Egyptian pilgrims to Jeddah—crammed spaces, inadequate sanitation, and profiteering shipping companies prioritizing revenue over safety.

Pilgrims endured the hardships with patience, driven solely by their devotion to Hajj. Asad also criticized the heavy financial burdens placed on pilgrims by the Saudi authorities and the chaotic scenes in Mecca during the 1927 pilgrimage—animals, cargo, and noise filling the sacred precincts.

He questioned the Wahhabi movement’s rigid enforcement of rituals, arguing that while its intent was to purge superstition, its harshness undermined that goal.

Asad found King Abdulaziz personally generous and fair, intelligent yet lacking a visionary leadership model. Though the King brought stability to Najd, Ha’il, the Hejaz, and Medina, it was enforced through strict laws, with limited efforts to expand education or build a truly just and progressive Islamic society.

Hajj as a New Beginning

Asad described his 1927 Hajj as a spiritual rebirth—the most powerful experience of his life. He remained in Mecca and Medina for nearly six years, studying Qur’anic sciences and Hadith under prominent scholars and immersing himself in Islamic intellectual circles.

He wrote:

“I spent more than five years in Arabia, most of them in Medina, to fully experience the environment where the Arab Prophet first preached this religion.”

Convinced of Islam’s enduring power despite Muslims’ flaws, Asad dedicated his life to defending Islam, clarifying its truths, and reshaping Western perceptions.

He supported the armed resistance of Libya’s Senussi movement and even undertook a secret mission on behalf of Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif to deliver strategic plans to Omar Mukhtar.

In 1932, Asad left Saudi Arabia to support Muslim communities in Turkestan, China, and Indonesia. Encouraged by Indian Muslim friends in Mecca, he traveled to India, where Muhammad Iqbal invited him to join the founding project of Pakistan.

Asad played a significant role in Pakistan’s establishment in 1947 and was granted citizenship. He later resigned his official roles and lived in Switzerland for a decade before settling in Tangier, Morocco.

Between 1964 and 1980, he worked on a new English translation and interpretation of the Qur’an and began translating Sahih al-Bukhari during his time in India.

In 1982, Asad moved to Spain, where he passed away on Thursday, February 20, 1992. He was buried in a small Muslim cemetery in Granada. His passing did not sever his bond with the Muslim world—his writings remain a testament to his enduring passion for Islam and his mission to convey its essence to the wider world.