In the 4th–5th centuries AH, the Islamic East witnessed a power struggle between two rival dynasties: the Sunni Abbasids in Baghdad and the Shiʿi Fatimids in Cairo. Each sought symbolic control over Mecca, which was more than a pilgrimage destination—it served as a potent emblem of political and religious legitimacy across the Islamic world.

At the dawn of the 5th century AH, Nāṣir Khusraw—a Persian poet and bureaucracy rising within the Ghaznavid and Seljuq courts—led a life of luxury, immersed in poetry, banquets, and wine, while pursuing worldly pleasures.

Approaching his forties, a profound inner turmoil began to eclipse his former joys. He drifted into deep despondency, haunted by the transience of his lifestyle. One troubled night, he fell into a dream that would irrevocably change the course of his life.

In his vision, an enigmatic figure rebuked him sharply for his excessive drinking and frivolous behavior, questioning, "How long will you continue to drink?" Khusraw defended his habit as an escape from worldly woes. But the mysterious interlocutor insisted that oblivion would never bring true peace. When Khusraw asked, “Where can I find reason and wisdom?” the figure replied, “Whoever strives will find,” then gestured toward Mecca and vanished.

Awaking with clarity, Khusraw resolved to transform his life. He performed ablution, prayed, and invoked God to aid him in forsaking sin. He pledged to undertake the pilgrimage, hoping it would rescue him from the crisis that had consumed him for forty years. He wrote:

“When I awoke from sleep, the vision stood before me in full, and deeply moved me. I said to myself: I have awakened from last night’s slumber, and it is time I awaken from the sleep of the forty years past. I pondered deeply and found that I would not find happiness unless I renounced all my former behavior.”

In our series "A Thousand Paths to Mecca," we trace the force behind the millions of caravans that threaded through continents, seas, and deserts, all converging on the sacred direction burning in hearts long before it reached the feet. We explore pilgrims' footsteps across eras and cultures—each bearing stories that culminate at the threshold of the Blessed House.

From Khurāsān to Mecca

In Rabīʿ I 438 AH, Khusraw sold most of his assets, settled his debts, resigned from the Seljuq administration, and left behind the palaces and politics of Khurāsān. With his younger brother and Indian slave in tow, he set out from Marw (modern Turkmenistan), journeyed to Nishapur in northeastern Iran, then northwards to the Caspian, through Anatolia, and onward to Syria—visiting Hama, Tripoli, Beirut, Saida, Tyre, Acre, Haifa. In Jerusalem (5 Ramaḍān 438 AH), he visited the Dome of the Rock and Prophet’s Tombs, and prayed in Al-Aqsa, nearing the prayer niche dedicated to the Second Caliph, ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb.

By mid-Ḍu‑l-Qaʿdah, he left Jerusalem for Mecca, arriving a decade later to perform the Hajj. He then journeyed back north to Jerusalem, before traveling overland to Fatimid Cairo.

Residing in Cairo for three years, he met Sultan al-Muʾizz li‑Dīn Allāh, attended Ismaʿīlī-dīni lectures by al-Shīrāzī, and converted to Ismaʿīlīsm under his influence.

During his stay, he completed Hajj four times. The second pilgrimage was on behalf of the Fatimid Sultan by sea. The third took place with the caravan of provisions and the Kiswa (covering) sent from the Fatimid court. On the fourth, he remained six months in Mecca, documenting his experience in his renowned Safarnama—one of the earliest Persian travel-hajiograhies—detailing the political, social, and cultural reality of 5th-century AH pilgrimage life.

The Hijāz Through Khusraw’s Eyes

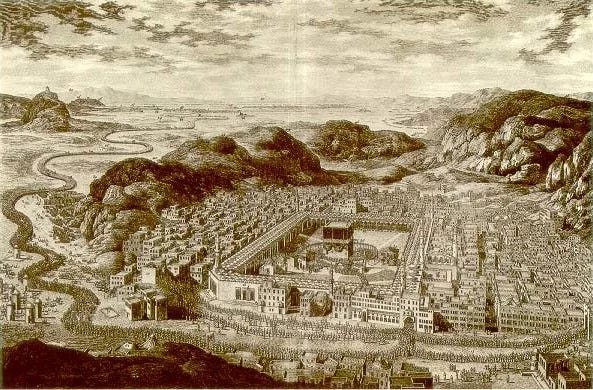

Khusraw admired the Kaʿba with reverence and drew a vivid picture of the rituals, cityscape, alleys, souks, urban texture, security apparatus, and the procession to ʿArafat. He noted the surrounding steep mountains enclosed by fortified walls, the arid land save for trees near the Kaʿba’s western gate (Bab Ibrahim), and the symbolic whiteness of the Fatimid Kiswa—a statement against the Abbasid black—surrounding structures such as the Zamzam well, Hajj fountain, and oil repository.

He observed chests inside the Haram used to store pilgrims’ belongings, originating from diverse regions like Maghreb, Egypt, Syria, Rome, Iraq, Khurāsān, and Mā Warāʾ al-Nahr. He described the plains of ʿArafat, the masjid where pilgrims prayed two units led by the Prophet Ibrahim, the Ḥajrat al-Jaʿrānah—four farsakhs north of Mecca—with two wells attributed to the Prophet and ʿAlī. Pilgrims baked dough there, sending bread across lands for blessing, and pointed out a rock from which Bilāl al-Habashī is said to have performed the call to prayer.

Khusraw detailed communal rituals—drumming to mark prayer times and the start of pilgrimage seasons, recital of the Qur’ān copied in ʿAlī ibn al-Zayd’s script, and pilgrims circling it with shaved heads. He listed 18 gates of the Haram, though names varied over centuries—a clue to historiographical change.

Population figures reveal about 2,000 Meccans and 500 outsiders. He marveled at rare fruits and vegetables and the bustling pilgrim season markets. A market before Mount Marwah hosted 20 shops for cupping and barber services, plus an apothecary market where Moroccan dinars were standard exchange. He noted that scholars were exempt from tax—he was welcomed by a prince accordingly.

Infrastructure & Patronage

He praised Abbasid water works: wells, reservoirs, cisterns, pilgrim lodgings, and campgrounds built by Baghdad’s caliphs. Provincial rulers too, such as Ibn Shaddāl of Aden, provided water to Mecca and ʿArafat via underground channels, completing cistern projects for pilgrims. Independent water vendors fetched water from nearby wells like Biʾr al-Zāhid, and the emir of Mecca lived in al-Barqah—four farsakhs north—surrounded by trees, water, and a private troop.

Khusraw recorded social and natural hazards of Hajj: Bedouin extortion, floods at Juhfah (the miqāt for Maghrebī pilgrims), famine caused by drought—wheat priced at 16 Moroccan dinars during his second pilgrimage in 439 AH—and plague-driven mob retreats to Egypt. In 440 AH, the Fatimid Sultan formally suspending Hajj due to famine.

The Hard Road Home

Post fourth-Hajj, he journeyed via southern Yemen. Braving deserts, he survived a bandit attack with his companions. After three grueling months, he arrived in al‑Baṣrah, impoverished and unable to enter even a public bath. He traveled through Isfahan and reached his birthplace, Balkh, in Jumādā al‑Ākhirah 444 AH, aged 50.

Although Sunni—or, as some claim, Twelver Shīʿī—early in life, Khusraw embraced Ismaʿīlīsm in Egypt. He was appointed the daʿī of Khurāsān and later hajjāt (a rank for Ismaʿīlī missionaries). Serving as a contender to spread the Fatimid creed, he was eventually seen as a threat by the Seljuqs, forcing him east to Badakhshān. There he settled in Yamgān, under local protection, and spent his final 25 years before passing in 481 AH—buried there.

A traveler of profound insight, Khusraw emerged a changed man after his pilgrimage. His post‑444 AH works reflect a total transformation: he renounced vanity to dedicate himself to spiritual and intellectual pursuits as a faithful follower of the Fatimid movement.