At the onset of the Israeli invasion of Gaza following October 7, 2023, an estimated 50,000 pregnant women—around 5,000 of whom were in their final month—were plunged into severe health and food crises due to Israeli attacks, according to Gaza’s Ministry of Health.

However, this suffering existed even before the Al-Aqsa flood. Reports from UNICEF confirmed that one in every four pregnant women in Palestine—25%—was at risk of dying during childbirth, a consequence of the occupation’s policies aimed, as described by the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, at restricting childbirth in Gaza.

What were already perilous pregnancy and birth conditions before the Al-Aqsa catastrophe worsened into “something worse than Hell after the deluge,” when childbirth had previously been a source of joy and celebration. Below, we explore the childbirth and nursing rituals in Palestine before the existence of “Israel,” drawing from contemporaneous sources:

Gustav Dalman, German orientalist, in Work, Customs, and Traditions in Palestine (early 20th century);

Alois Musil, Austrian orientalist, in Arabia Petraea (late 19th–early 20th century);

Tawfiq Kanaan, Palestinian researcher, in The Saints and Islamic Shrines in Palestine;

Sharif Kanaaneh et al., Procreation and Childhood: A Study in Palestinian Culture and Society;

Nidal Taha, Popular Rituals and Beliefs from Palestine.

Birth and Its Rituals: “Relief upon your head, relief from your distress.”

Late in pregnancy, women prepare by gathering wild herbs—bluf and basa‘miya—drying and grinding them into a flour with oil. The expectant mother eats this during labor, believing it nourishes and aids delivery.

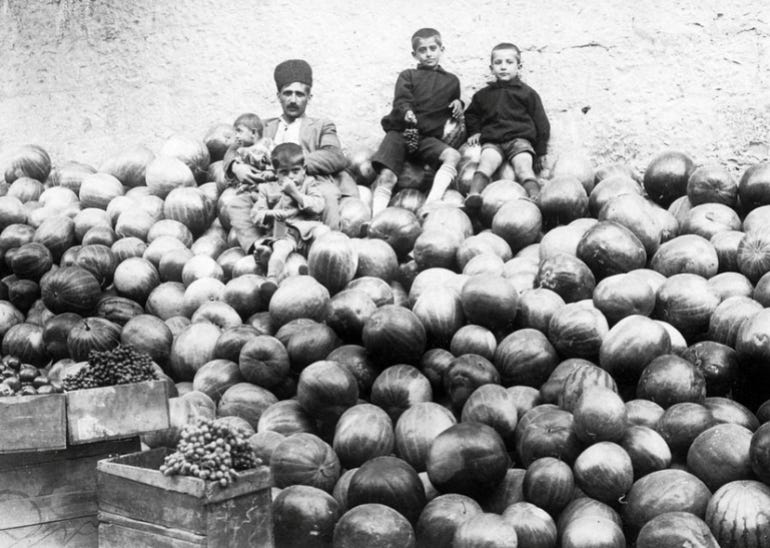

The mother-to-be receives chickens, rice, and other essentials called al-hamoola (“the load”) from family in her final month for extra nourishment during childbirth.

She might visit a local shrine, making vows—offering dates, the dish mujaddara, or even a sacrifice—asking for a safe delivery of a male child.

To protect against evil spirits or envy, she may receive a protective amulet or blue bead from a religious elder, wear a prayer-bead necklace over her belly, recite the Quran, and pray.

When labor begins, the woman sits on a birthing stone (hajar al-julus) rather than lying in bed, flanked by female relatives and attended by a midwife (dayyah), with her mother often present. If no stone is available, alternatives include a chair, an overturned clay pot, or a stack of bricks.

If labor stalls, those around chant prayers and place blessed rosaries on her belly and neck. The midwife recites an ancient, folkloric blessing invoking prophets and divine power:

“Relief upon your head, relief from your distress, O Noah, O Noah, O spiritual deliverer...”

These practices transcended religious lines. Even Christian families in areas like Beit Jala sought help from Mary and saints, with priests praying and women wearing crosses for protection.

Once the baby’s head appears, the midwife prays:

“I stretch my right hand and trust in You, Lord of the Worlds... I stretch my left hand and trust in You...”

After the birth, she performs a blessing:

“I have enveloped you with Jacob’s children under the tree… in the name of He who gave you breath…”

She then carefully delivers the placenta, known as al-khalasah (“the deliverance”), thought to be the child’s spiritual twin and guardian. It’s tied and placed respectfully—often buried or stored in a clay jar—to preserve the child’s well-being and future fertility.

Muslim families avoided Friday births, seeing them as bad omens—they would sacrifice an animal and sprinkle its blood on the home and child. Generally, an aqiqa sacrifice was performed for newborn boys (and sometimes girls), but the blood was not sprinkled unless the birth fell on a Friday.

Welcoming the Newborn (Al-Khiryān) and Naming

Three days after birth, the newborn is anointed with oil, swaddled, washed with sheep’s urine, swaddled again, and nicknamed khiryān until they are formally named. On the seventh day (al-sabu‘), they’re bathed again with clean water.

Some families delay the newborn’s first bath up to a month, believing angels wash the baby at night. When the bath finally occurs, they sing lullabies and sprinkle perfume, salt, and blessings.

On day seven—or sometimes at the 40-day milestone—the baby visits their paternal or maternal grandfather, accompanied by a sheep or goat for an aqiqa. A green ribbon is tied to the animal, and the grandfather gives the baby its name in a ceremony:

“O Lord, accept this (goat or lamb) as an offering for the son of so‑and‑so...”

Friends and relatives are invited to a feast and bring gifts, especially for the new mother.

In traditional folktales, male births are preferred over female ones—“A daughter is a house-breaker; a son builds the home.” Both Muslim and Christian families share this cultural bias, separate from religious decree.

At the aqiqa, a lock of the baby’s hair is cut. In many areas, this happens a year—or even two—after weaning. Parents may keep hair, tucking it in the mother’s pillow or wall; headaches in the mother could signify the hair’s misuse.

Names reflect religion and lineage: Muslims favor prophetic or theophoric names (e.g., Muhammad, Abdullah), and Christian families choose Biblical names in Arabic, especially ones linked to saints' feast days. Others select aspirational names like Sa‘d, Saeed, Tawfiq, or naturist names referencing animals, plants, or months.

Christians name newborns immediately but formalize the name at baptism around day 40. A priest submerges the baby three times in holy water, cuts a cross-shaped lock, anoints them, and officiates with godparents and celebratory gifts and feast, similar to the Muslim aqiqa.

Nursing and Lulling: “Nurse, little fava bean...”

Nursing was intended for two years per Quranic guidance, though often interrupted due to rapid subsequent pregnancies. A mother’s success in breastfeeding was culturally esteemed, associated with fertility and strength.

During lactation, families performed a ritual: placing seven fava beans in water and chanting:

“Nurse, little fava bean, grow like the little stalk...”

As the beans swell, it symbolized the baby’s growth and appetite.

Babies were soothed through hadhhadah (gentle rocking and lullabies) by a family member, allowing the mother to complete household chores before breastfeeding. Lullabies included:

“O valley dove, bring sleep to my child...”

At six months, with the eruption of first teeth, an aunt would massage the gums—never the maternal aunt, as it was believed only a paternal aunt (‘ammah) could ensure strong teeth.

Weaning in summer was avoided; spring was preferred when animal milk supply peaks (“Wean in March even if the child is a tear”). Goat’s milk, boiled and sweetened, often supplemented.

These joyful and deeply human childbirth and nursing traditions, even when interwoven with superstition, honored the child as more than a physical being—but a spiritual continuation of ancestral life and identity.

Today, Palestinian birth remains a form of resistance—a tool against the settler-colonial erasure of indigenous inhabitants. The newborn embodies hope in the face of loss: “He who reproduces never dies.”