In a striking statement that once again brought the Qandil Mountains into the spotlight, Syrian President Ahmad al-Shara described the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leaders hiding there as “people cut off from social life for over 40 years.”

The comment came as part of al-Shara’s emphasis on the need to protect Syria’s Kurdish population and integrate them into national institutions. He warned against “cornering the Kurds into an armed faction with foreign affiliations,” calling it “a strategic error against them.”

Despite the PKK’s announcement of its dissolution and disarmament as part of a historic peace deal with Ankara following four decades of conflict that claimed more than 40,000 lives its fighters and commanders continue to live in the caves of Qandil.

Their continued presence raises questions about the enduring significance of this mountainous stronghold and its complex role in the region’s overlapping conflicts.

A Mountain Fortress at the Junction of Three Nations

The Qandil mountain range lies in the northeastern tip of Iraq, bordering both Turkey and Iran. It is part of the rugged Zagros range and has historically served as a natural border between the Ottoman and Persian empires. Owing to its dense Kurdish population, the region is often seen as part of what is known as “Greater Kurdistan.”

The area’s harsh terrain and towering peaks—some rising above 3,000 meters—have made it virtually impenetrable for decades.

Kamran Qardaghī, former adviser to late Iraqi President Jalal Talabani, recalls a grueling 1974 trek on foot from the town of Rania, crossing seven mountain ridges to reach the remote Qandil outposts. He described the mountains as a “natural fortress,” difficult to invade but easy to defend for those entrenched within.

The lack of paved roads and treacherous geography turned the area into a natural haven for insurgent groups, far from the reach of the militaries of Iraq, Turkey, and Iran.

Following the 1991 Gulf War, Qandil became part of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq an autonomous area creating greater space for militant operations due to the political sensitivity of direct intervention by either Baghdad or Erbil.

These geographic and political conditions laid the foundation for Qandil’s transformation into a near-perfect base for prolonged guerrilla warfare something the PKK quickly recognized and capitalized on.

PKK’s Ascent to the Peaks of Qandil

After the Gulf War and the Kurdish uprising against Saddam Hussein’s regime in 1991, the PKK seized the opportunity to move into Qandil, exploiting the power vacuum and chaos.

Qardaghī, who witnessed the events firsthand, says that PKK fighters first entered Qandil in 1991 and solidified their presence by 1992, slipping in through Iran and establishing permanent bases in the mountains.

Throughout the 1990s, the PKK clashed violently with the two main Kurdish parties in Iraq the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Talabani, and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), led by Masoud Barzani. These parties, under pressure from Turkey and Iran, sought to curb the PKK’s expansion.

One of the fiercest confrontations occurred in 1997 when Kurdish factions launched a regional-backed campaign to oust the PKK from Qandil, temporarily forcing the surrender of some 2,000 fighters. Yet remnants of the group returned to their mountain sanctuaries through complex smuggling routes once the offensive subsided.

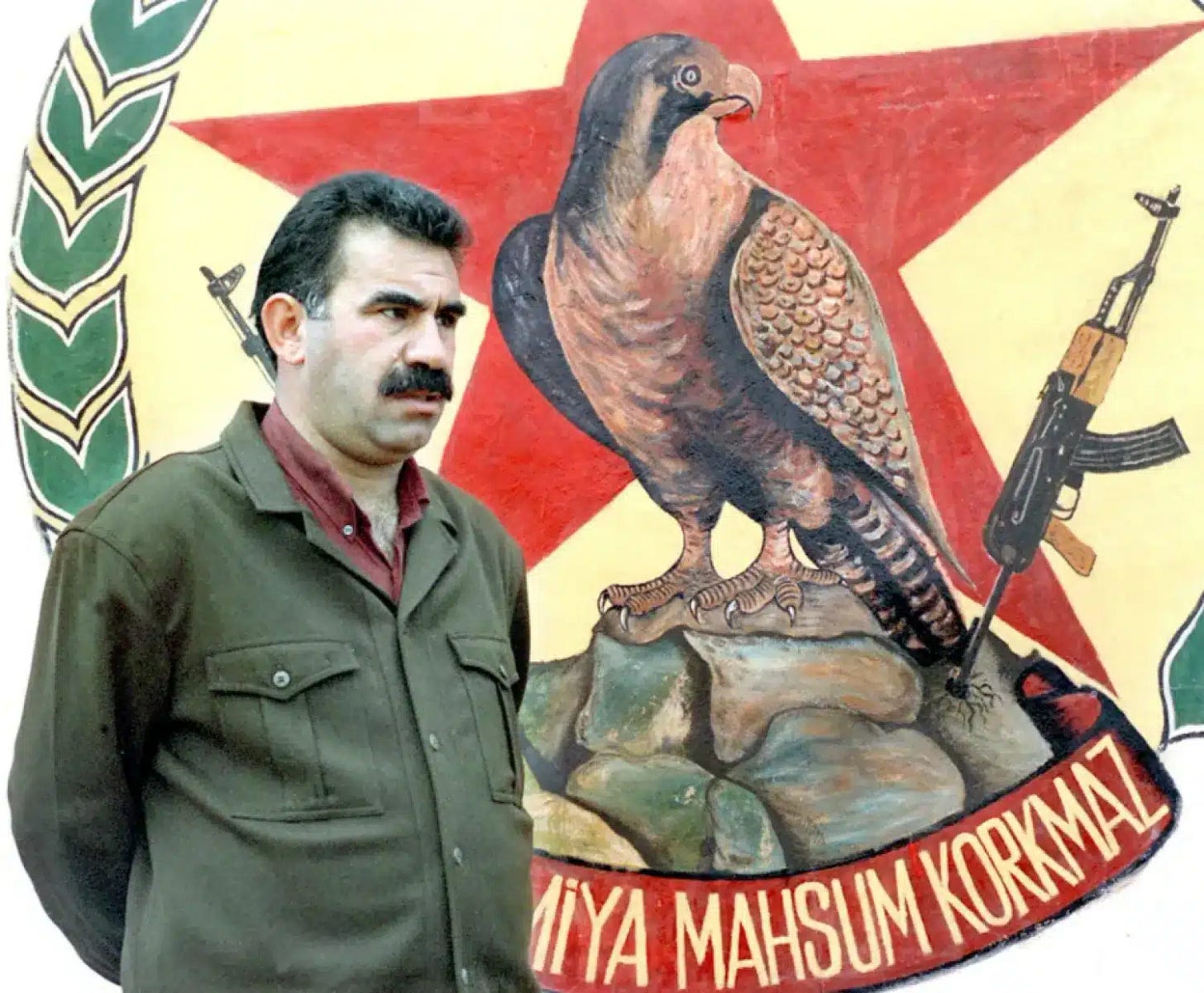

By the late 1990s, the PKK had firmly established Qandil as its strategic command center. After Turkey captured its founder, Abdullah Öcalan, in 1999, a new leadership took over figures like Murat Karayılan, Cemil Bayık, and Duran Kalkan, collectively known as the “Qandil Command.” Most are Turkish-born Kurds.

Under their leadership, the PKK evolved from a secretive Marxist movement into an organization with its own ideological framework ”Democratic Confederalism” inspired by Öcalan’s writings during his imprisonment. The group also reorganized under a broader umbrella, the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK), uniting various Kurdish militant factions from Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran under a central command in Qandil.

Qandil’s role expanded beyond sheltering Turkish PKK militants. Starting in 2004, it became home to the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), the PKK’s Iranian wing, which launched insurgent operations inside Iran. Similarly, early cadres of Syria’s People’s Protection Units (YPG) found refuge and training in Qandil.

In effect, the mountains became a transnational Kurdish reservoir, uniting fighters from across the region under a shared nationalist vision. By recent estimates from the International Crisis Group, some 7,000 fighters were entrenched in Qandil a testament to the scale and sophistication of its militarized infrastructure.

Qandil Becomes a Regional Knot

The Qandil Mountains have become a symbol of resistance to regional powers, and at times a battlefield for proxy wars between them and Kurdish factions.

For decades, Turkey has viewed Qandil as a “terrorist hub” from which the PKK launches attacks. Ankara has regularly bombarded the area and, on several occasions, threatened ground invasions. One of the most notable came in mid-2018, when President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan vowed to “drain the terror swamp in Qandil” and raise the Turkish flag there.

While Turkish forces have carried out limited incursions into northern Iraq, fully seizing Qandil remains elusive—a challenge analysts attribute to the scale of military resources such an operation would require, particularly as the Turkish army remains entangled in the Syrian theater.

In recent years, however, Ankara has adjusted its tactics, establishing forward bases inside Iraq and deploying drones to target PKK leaders even in remote enclaves undermining the fighters’ longstanding sense of security in the rugged terrain.

To the east, Iran also sees the Kurdish presence in Qandil as a security threat. The Iranian PJAK has engaged in bloody clashes with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps over the past two decades. Tehran has frequently responded with cross-border artillery strikes targeting Qandil’s highlands, often forcing the evacuation of Kurdish Iraqi villages.

Beyond Turkey and Iran, Qandil’s complications extend to Syria. Ankara has long maintained that Syria’s YPG is essentially an offshoot of the PKK headquartered in Qandil.

During the Syrian civil war, PKK commanders in Qandil maintained strong ties with YPG leadership. Notably, senior PKK figure Bahoz Erdal was widely reported to have advised Kurdish forces in Syria further weaving Qandil into the region’s tangled conflicts.

Life Inside the Mountains

Within the caves and scattered camps of Qandil, a self-contained society has emerged over the years one governed by its own rules, far removed from civilian life. Former defectors from the PKK have described life there as follows:

Fighters live in isolated barracks and undergo daily ideological training centered on Öcalan’s teachings.

A self-sufficient system includes schools, training camps, field hospitals, internal courts, and even centralized media.

The environment is tightly controlled, resembling a real-life version of Squid Game, as one defector put it.

“Mountain law” enforces strict discipline and punishes dissent or attempted defections harshly. Solitary confinement cells in Qandil are reportedly rarely empty.

In 2007, Abdullah Öcalan’s brother Osman was placed in solitary for three months simply for suggesting internal reforms.

The Qandil leadership promotes a lifestyle that cuts fighters off from the temptations of civilian life. Romantic relationships and marriage among members are strictly prohibited, as they are seen as distractions that undermine revolutionary discipline.

An internal manual explicitly states that “emotions are a weakness” unworthy of a “committed revolutionary.”

A Perennial Enigma

Today, even amid calls for peace and disarmament, particularly after 2025 initiatives, Qandil remains a mysterious and unresolved chapter. The stronghold still poses a significant challenge to any comprehensive settlement of the Kurdish issue especially given the fighters’ refusal to descend from the mountains and the lack of a clear plan to reintegrate armed Kurds in Syria.

And so, as many hope for an end to the conflict, one question persists:

Will the world ever witness the final descent of fighters from Qandil’s peaks, closing the book on the “mountain war”?

Or will the region’s geopolitical terrain prove even more forbidding than Qandil’s crags, keeping the embers of conflict smoldering beneath a fragile ceasefire?