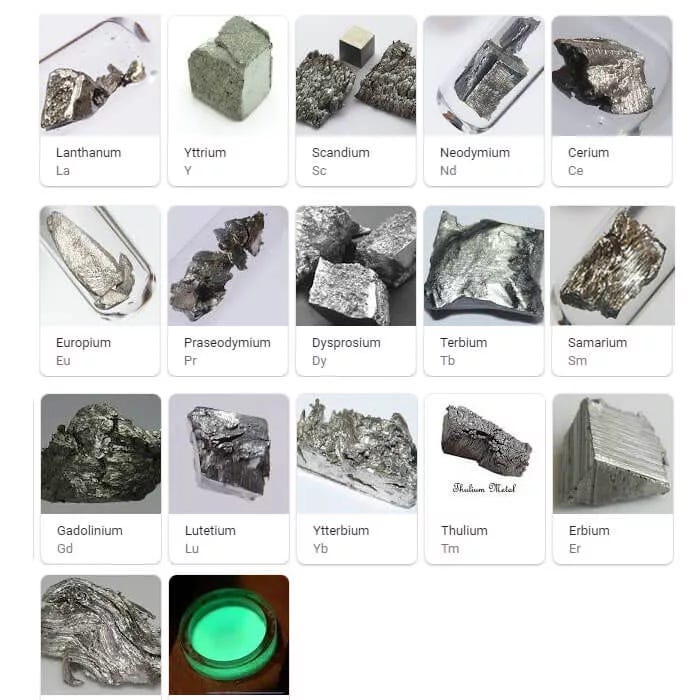

Amid the global race for tomorrow’s technologies, rare earth elements those 17 “magical” minerals have emerged as one of the hidden axes of geopolitical competition in the 21st century. With China controlling the lion’s share of their supply chain, it has become the near-exclusive provider connecting electric vehicles, fighter jets, wind turbines, and even satellites to the world of critical minerals.

On October 9, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced new export restrictions on rare earths and related products, including technologies and equipment used in mining and refining. These restrictions were far from arbitrary they came in response to renewed trade tensions with the United States under Donald Trump’s second administration, which had imposed new tariffs on Chinese imports.

Chinese Sanctions Shake the West

The announcement sent shockwaves through European capitals, where industries such as automotive and defense depend on China for up to 90% of their rare earth supply. In Brussels, the European Commission warned that the move could paralyze vital supply chains, jeopardizing the EU’s green transition goals for 2030.

Washington responded with swift negotiations, culminating in a deal to maintain the flow of critical minerals to Boeing and Tesla factories. In return, China committed to purchasing 12 million metric tons of American soybeans before the end of 2025, and 25 million tons annually over the next three years, alongside the resumption of sorghum and timber imports.

For its part, the U.S. reduced tariffs on certain Chinese imports and extended a moratorium on retaliatory duties for one year, postponing the implementation of a planned 100% tariff on Chinese exports originally slated for next month.

The deal was struck during the October 30 meeting between President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Busan, South Korea their first talks since 2019. But while Trump hailed the agreement as a “huge win,” it exposed stark divergences in Western strategies. Washington opted for a quick bilateral fix, while Brussels rejected unilateral negotiations.

A day after the Busan summit, the G7 met in Toronto and announced the creation of the “Western Wall” a rare earth alliance led by Canada and joined by nine other countries: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway, the United States, Australia, and Ukraine as a strategic partner. Together, they pledged $4.55 billion in investments for 26 projects in graphite, rare earth elements, and scandium processing.

Earlier, on October 20 in Washington, Trump and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese signed an $8.5 billion critical minerals agreement aimed at breaking China’s monopoly over gallium (100% Chinese) and rare earth magnets (90% Chinese). Each country committed to investing at least $1 billion within six months in 12 priority joint ventures supporting defense and clean energy industries.

Unlike its European allies, the U.S. has pursued a trade diplomacy strategy that buys time mindful that Beijing still holds critical minerals as a bargaining chip in future disputes. This strategic divide reflects a longstanding contrast: America’s direct-deal approach versus Europe’s collective, alliance-building strategy to counter Chinese monopolies.

U.S. Rebuilds Domestic Industry, Germany Feels the Strain

Recognizing China’s leverage, Washington began building a domestic rare earth production base, backed by the Department of Defense. More than $550 million was invested in MP Materials and Noveon Magnetics to expand mining and refining in California and develop new magnet factories on American soil over the next decade.

In Germany, China’s export restrictions sparked alarm in the defense sector, which relies on rare earths for fighter jets, submarines, and sensor systems. Berlin is now acutely aware of its vulnerability to China’s dominance in this critical market.

The German auto industry, too, faces serious concerns over potential production halts due to shortages of rare earth elements and magnets essential for electric motors, braking systems, and sensors.

The German Automotive Industry Association warned that China had issued only a limited number of export licenses insufficient to meet the demands of major firms like Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, and Bosch.

Meanwhile, Paris unveiled a national plan to conduct a comprehensive geological survey of France’s mineral resources. With French industries from EVs to aerospace and defense heavily reliant on Chinese components, President Emmanuel Macron urged the EU to activate its Anti-Coercion Instrument, the bloc’s toughest trade tool to date.

This legal mechanism is designed to deter economic blackmail by allowing retaliatory tariffs or restricting market access to companies from coercive states. However, Macron’s proposal unprecedented in EU trade policy risks triggering retaliatory measures rather than restoring balance, even if France is justified in testing Europe’s resolve.

Amid this industrial alert, the EU funded the opening of the largest permanent magnet plant in Narva, Estonia near the Russian border with €14.5 million in support. Canada’s Neo Performance Materials aims to produce 2,000 tons annually, scaling to 5,000, to meet demand from wind turbine and EV battery makers.

China’s “Silent Weapon”

To date, China retains its grip on global supply chains critical to national and economic security, dominating roughly 70% of rare earth mining and 90% of global refining a result of strategic investments accumulated over decades.

As Western mines declined due to environmental concerns, Beijing became the de facto gatekeeper for the components powering electric cars, satellites, and even F-35 fighter jets each containing over 440 kg of rare earths. A Virginia-class submarine needs 4,200 kg.

China’s quest began in the 1990s when then-leader Deng Xiaoping famously declared in 1992: “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” Since then, Beijing has consolidated control over global supply chains not because it holds the largest reserves, but because it systematically invested in refining and processing technologies. Despite setbacks, China persisted until it secured dominance in the sector.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and other industrialized nations lost much of their processing expertise due to economic slowdowns and disinvestment, while China supported the sector through deliberate government policy making it a pillar of its geopolitical and economic strength.

By 2010, China’s share of global rare earth production peaked at 95%, before dropping to 60% by 2019 amid international efforts to diversify. Beijing doesn’t just possess geological wealth it controls the entire value chain, from exploration and chemical separation to magnet production.

Past Precedents: Japan and Trump

China has at times deployed rare earths as a “temporary gun” in diplomatic disputes. In 2010, during a maritime standoff with Japan over the detention of a Chinese crew, Beijing abruptly cut its rare earth exports to Japan, disrupting its tech industry and forcing Tokyo to back down within weeks.

This showcased China’s ability to convert industrial might into political leverage. However, such moves are short-term and tactical rather than sustained strategic weapons.

A similar pattern emerged during the 2018–2019 U.S.–China trade war, when Chinese state media hinted that rare earth export controls could become a “powerful weapon” against the U.S.

In April 2025, China retaliated against new U.S. tariffs by tightening restrictions on seven rare earth elements. Western automakers faced immediate shortages, with some forced to halt production for weeks due to a lack of critical magnets.

Though some of these measures were later eased or negotiated, China’s record shows a consistent willingness to weaponize its rare earth advantage in times of crisis.

China’s Corporate Octopus

Globally, China has reinforced its strategy through acquisitions and investments in mining projects. In Africa, the past decade has seen unprecedented Chinese flows into strategic mines including stakes in copper, lithium, and cobalt mines across the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar.

In 2023 alone, China committed $21.7 billion to construction and investment projects in Africa the highest for any region with $7.8 billion directed at mining. This includes MMG’s $1.9 billion acquisition of copper mines in Botswana and investments in cobalt and lithium operations in Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Strategic mineral demand is also driving Chinese infrastructure projects across the continent. In January 2024, Chinese firms announced $7 billion in new infrastructure investments tied to revised mining agreements in the DRC.

Through its Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing is also securing major mineral resources in Latin America and Australia. While many projects support civilian industries like renewables and tech, the implications extend to defense. This global web of Chinese companies and projects mirrors Beijing’s domestic rare earth strategy.

The West’s Push for “Mineral Independence”

In response, Western governments are seeking gradual “mineral independence.” The EU launched a Critical Raw Materials Act to encourage local mining and set targets including extracting 10% of domestic needs and processing 40% within the bloc by 2030.

Swedish company Leading Edge Materials is preparing to restart rare earth extraction at the Norra Kärr mine in southern Sweden. State-owned LKAB plans to recover 2,000 tons of rare earths from waste at an old steel mine in the north. In France, the Solvay chemical group is expanding rare earth magnet production to meet 20–30% of European demand.

But reducing dependence on Chinese rare earths requires a comprehensive strategy from financing and technology to flexible regulations and partnerships. While geological alternatives, such as the 2022 discovery in Turkey, offer hope, turning them into commercially viable supply chains will take years and face local and environmental opposition.