In a gesture reminiscent of French President Emmanuel Macron, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi made a brief evening visit on Monday, June 3, to the famed Khan El-Khalili heritage district in the heart of Cairo. He strolled through its historic alleyways and performed the Maghrib prayer at the Imam Hussein Mosque, during his regional tour that includes stops in Egypt and Lebanon.

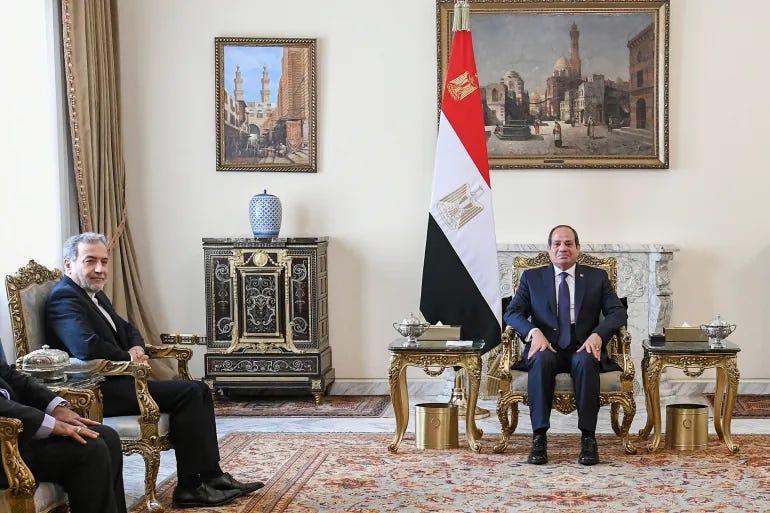

During his two-day visit to the Egyptian capital, Araghchi met with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and his Egyptian counterpart, Badr Abdel Aaty. According to Iran’s state news agency IRNA, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Esmail Baghaei reported that the talks focused on bilateral relations and consultations on regional and international developments, especially the situation in occupied Palestine and water security issues in the Red Sea.

This visit cannot be viewed as routine or part of a traditional diplomatic agenda. It comes amid intense regional and global pressures on both countries—efforts to marginalize Egypt and diminish its regional role on one side, and mounting pressure on Iran over its nuclear program on the other.

Over the past two years, there have been signs of a mutual and growing desire between Cairo and Tehran to reach a diplomatic convergence that could restore relations to their pre-1979 rupture. Both foreign ministries have been working extensively to craft a new normalization roadmap, based on entirely different premises than in the past.

Redrawing the Middle East

Araghchi’s visit comes at a time when the Middle East is undergoing a profound reengineering of its regional architecture. Longstanding foreign policy paradigms are being upended, compelling both Cairo and Tehran to reassess their positions in light of the evolving landscape.

Among the most consequential shifts has been the rapprochement between Tehran and Gulf states, along with pressure on Syria’s new administration to normalize ties with Israel—whose growing influence in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine is raising alarms. Recently reopened channels between Riyadh and Damascus and the signing of multiple economic agreements have further unsettled Cairo, particularly amid rising tensions with Ethiopia over the Grand Renaissance Dam.

These developments unfold against a backdrop of mounting—though officially denied—tensions between Egypt and Washington, as well as with Gulf capitals, notably Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. Meanwhile, Iran’s nuclear negotiations have entered a new phase of complexity, with the Trump administration again hinting at renewed sanctions.

Added to this is the uptick in regional security tensions, including intermittent Israeli military operations against Iran, which threaten regional stability and maritime safety in the Red Sea—developments that could have disastrous ripple effects throughout the region.

At the same time, Washington is attempting to impose a new regional alignment shaped by different rules—ones that suit the Israeli agenda. This emerging order places Gulf capitals at the center of influence, often at the expense of traditional powerhouses like Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, and Tehran.

In such a climate, traditional alliances have become practically irrelevant. Marginalized and ineffective, they have prompted regional powers—including Egypt, Iran, and Iraq—to explore alternative alignments that could restore balance and counter the influence of new coalitions inviting Western military re-engagement in the region.

What Does Cairo Want?

Crucially, it was Egypt that extended the invitation to Araghchi—perhaps for the first time as a standalone bilateral initiative, rather than within the context of multilateral conferences or regional forums. This marks a clear indication of Cairo’s intent to step up rapprochement with Tehran.

The invitation coincides with a notable decline in Egypt’s regional clout. Once a key player in Sudan, Libya, Yemen, Lebanon, and Syria, Cairo now finds itself increasingly sidelined—even in the Palestinian file, where its geographic proximity once ensured a pivotal role. That influence has diminished considerably, especially since the U.S. administration opened direct lines of communication with Hamas.

This marginalization may be both a cause and a result of Cairo’s strained relations with the U.S. and Israel, particularly over its public opposition to population displacement schemes and its refusal to comply with American demands. President Biden seems intent on punishing his regional ally by pushing him off the regional stage—a reality underscored by Sisi’s exclusion from the most recent Gulf-Islamic summit in Riyadh following Trump’s visit.

The aggressive regional diplomacy of Egypt’s Gulf allies—often excluding or overlooking Cairo’s views—has compounded the tension. Whether it’s their warming ties with Washington and Tel Aviv or their unilateral meddling in files critical to Egyptian national security, the result is an increasingly isolated Egypt facing a political conundrum.

From this context emerged Egypt’s latest push to reclaim regional relevance—and Tehran may now be a key gateway. Cairo appears poised to act as a mediator between Iran and the U.S. in the nuclear file. Araghchi’s visit coincided with that of IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi, also in Cairo—an alignment too precise to be mere coincidence.

Indeed, a trilateral meeting was held between the Egyptian and Iranian foreign ministers and the IAEA chief, signaling Cairo’s bid to mediate. This comes on the heels of a recent IAEA report accusing Iran of escalating uranium enrichment. From the American side, Egypt’s foreign minister received a call from U.S. Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff regarding the latest developments.

Thus, Egypt views rapprochement with Tehran as a means to expand its restricted regional maneuvering space and reassert its diplomatic agency. The strategic use of Iranian relations is also a message to Washington, Tel Aviv, and the Gulf capitals: Egypt’s regional presence is far from over, despite ongoing efforts to isolate it.

What Does Tehran Want?

Tehran, meanwhile, is facing mounting American and European pressure over its nuclear ambitions and steadfast rejection of U.S. demands to cease uranium enrichment and abandon its bomb-making capabilities. Iran’s defiance has triggered threats of additional sanctions and prolonged its international isolation.

Iran sees Egypt—alongside Riyadh, Doha, and Muscat—as a potential intermediary in bridging the chasm with Washington. Cairo’s historical and cultural weight, coupled with its generally stable U.S. ties—despite recent turbulence—make it a valuable diplomatic conduit.

After setbacks in Syria and Lebanon, Iran is seeking a foothold to maintain at least a minimal level of regional influence. Hence Araghchi’s diplomatic whirlwind in recent months, seeking dialogue with powers across the region, even those with historically frosty ties to Tehran.

In particular, Iran aims to forge an informal regional front with Egypt against American threats, leveraging Cairo’s geopolitical stature to deter the U.S.—and by extension Israel—from military escalation. A full-scale war would be catastrophic, potentially dooming Iran’s long-cherished nuclear aspirations and even threatening the core of its political system.

A Pragmatic Rapprochement

Contrary to common media narratives portraying Egypt-Iran relations as entirely severed, the truth is more nuanced. Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, ties have been more dormant than nonexistent, marked by periods of stagnation rather than total rupture.

Over the past four decades, bilateral relations have seen various fluctuations—often dictated by Cairo’s alignment with Gulf states, which historically discouraged rapprochement with Tehran.

Today, that obstacle no longer exists. The restoration of full diplomatic ties between Iran and several Gulf states has paved the way for Cairo to explore a similar path—especially given the shared regional challenges making such a rapprochement more necessity than luxury.

From a purely pragmatic standpoint, Egypt is now looking to deepen ties with Iran—a country it was once related to by marriage, when the late Shah wed Princess Fawzia, sister of King Farouk, who briefly became Empress of Iran before their divorce.

Many analysts suggest that constructive dialogue and a potential thaw between Tehran and Cairo could unlock significant opportunities for cooperation, particularly in energy and trade. With both countries possessing considerable potential and facing daunting challenges, the conditions seem favorable for a promising partnership that could yield strategic gains on both sides.

Since 2021, early signs of secret diplomatic engagement have emerged. The first came in November 2022, when then-Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry met Iranian Vice President Ali Salajegheh on the sidelines of COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh.

The following month, President Sisi met then-Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian during the “Baghdad II” conference in Jordan. Several other meetings followed—at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank gathering in Sharm El-Sheikh in September 2023, and again two months later between Iranian parliament speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and Egyptian House Speaker Hanafy Gebaly at the BRICS Parliamentary Forum in South Africa.

The rapprochement culminated in the December 2024 visit of Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian to Cairo for the 11th D-8 summit—marking the first visit by an Iranian president to Egypt in 11 years, and only the second in 45 years, following Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s 2013 trip.

Clearly, both Cairo and Tehran now recognize that the current geopolitical climate demands a new level of engagement—one that transcends superficial diplomacy. For Egypt, this relationship could serve as a pressure lever and regional reentry point; for Iran, it may be a lifeline for preserving influence and deterring aggression.

The potential for this rapprochement is vast, grounded in shared interests and historical ties. But its success will largely depend on both sides adopting a rational and balanced strategy—one that advances their mutual goals without jeopardizing their ties with Gulf and Western allies.