Read the interview in Arabic

Syria’s momentous transition today-following its liberation from the Assad regime, which ruled by iron and fire for some 55 years-harkens back to a similar pivotal moment in Syrian political memory a century ago: 1920. That year marked the birth of the “Arab Kingdom of Syria,” the Levant’s first pioneering experiment in parliamentary democracy-an experiment that, had it been allowed to survive, would have transformed the face of our country and the entire region.

At that time, the “Syrian General Congress” convened in 1919 under the leadership of King Faisal I bin Hussein. He agreed to become the first Arab monarch to subject his rule to a constitution, enshrining a model of “civil, representative monarchy” where sovereignty belongs to the nation, not the ruler.

Supported by the wisdom of the Congress’s president, the Islamic reformer Sheikh Rashid Rida, the Congress succeeded in that brief period in reconciling Islamic identity with the values of a civil state. They crafted the 1920 Constitution, which established full equality among Syrians regardless of their religious or ethnic backgrounds.

Yet, this nascent parliamentary experiment, which was ahead of its time in the region, soon crashed against the wall of Western colonial ambitions. France and Britain refused to accept a sovereign, free model that threatened their interests.

The decisions of the San Remo Conference legitimized the Mandate, followed by the military advance led by General Gouraud, who crushed the Syrian dream at the Battle of Maysalun in July 1920. Military force thus ended a political project that could have altered the region’s trajectory for the next century.

We revisit this history today with its most prominent historian, Professor Elizabeth Thompson, author of “How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs”. In this interview, we discuss how Syrians today can reclaim that “lost legacy,” and how, in their new republic, they can avoid the traps of “minority protection” and international guardianship-pretexts used a century ago to destroy their first attempt and tear apart the societal fabric.

Who is Professor Elizabeth Thompson?

Elizabeth Thompson is a leading American scholar and historian of Middle Eastern studies. She holds the Mohamed S. Farsi Chair of Islamic Peace at American University in Washington, D.C., specializing in the dissection of political and social transformations in Syria and Lebanon during the Mandate era. Her award-winning work is distinguished by its success in illuminating Arab constitutional experiments that were deliberately obscured from the global historical record.

Professor Thompson is widely regarded as one of the most influential contemporary academic voices deconstructing colonial narratives in the Arab Levant. Her publications serve as international benchmarks for understanding the nexus between citizenship, gender, and the state in post-colonial societies.

The core of her scholarly contribution lies in shattering stereotypes surrounding “Arab Democratic Exceptionalism.” Through her rigorous research on Syria and Lebanon, she has demonstrated that the obstacles to democracy were not cultural, but rather the result of structural and legal interventions imposed by colonialism.

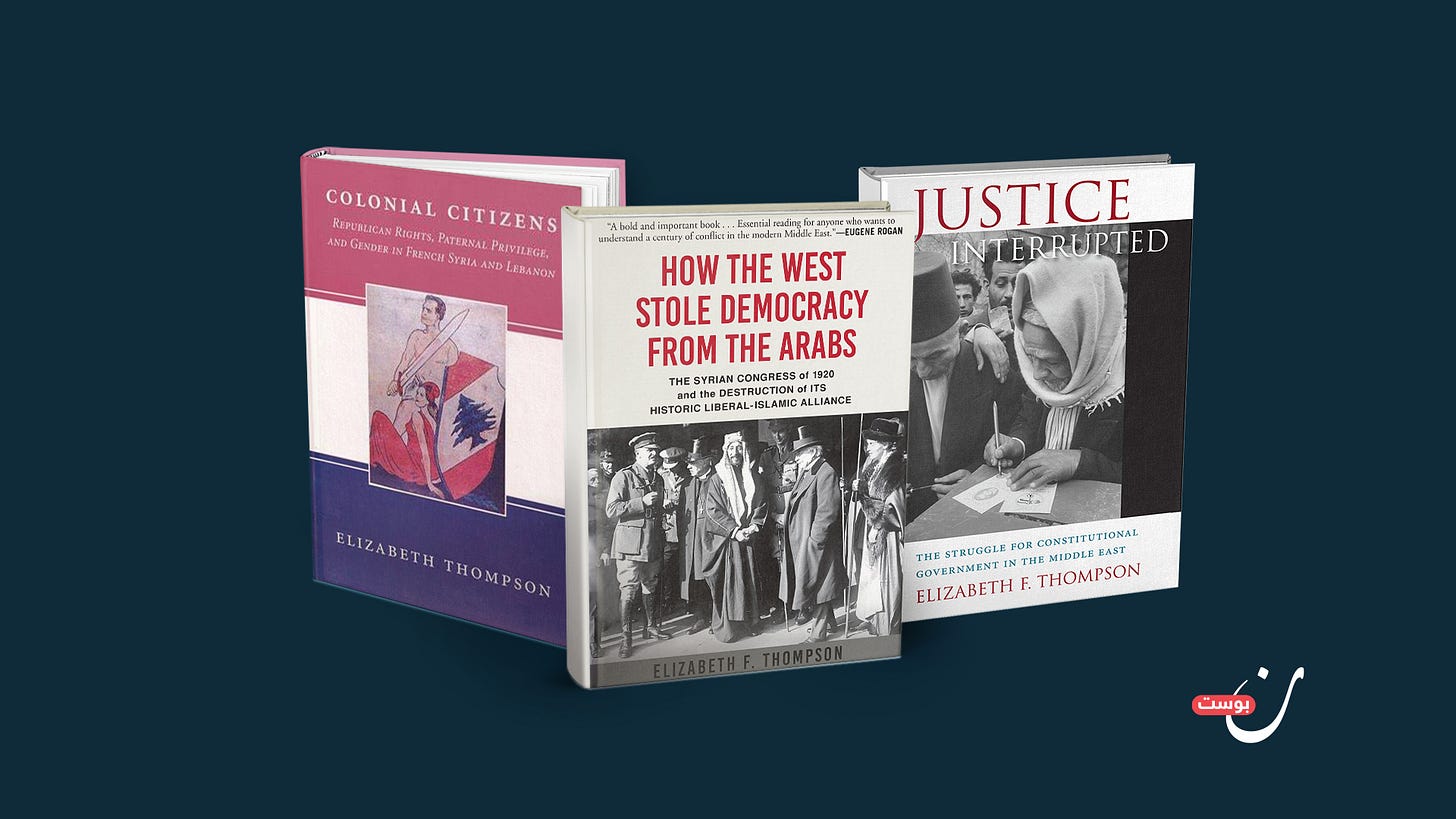

Major Works:

How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs: The Syrian Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of its Historic Liberal-Islamic Alliance

Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East

Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon

In your book “How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs”, you document the Syrian attempt to establish a democratic system in 1920. Now, more than a century later and following the fall of the Assad regime, do you believe Syria is facing a second historic opportunity?

Or do international circumstances continue to obstruct this path as they did a hundred years ago?

A century after Syria’s democratic, parliamentary democracy was demolished by the French, Syrians face an opportunity to recoup the democratic and tolerant political culture that their society held before colonial occupation. In 1920, a religious leader wearing a turban presided over a congress that drafted and ratified what I consider the most democratic constitution in modern Arab history.

It established a representative government based on equality before the law, regardless of religion, class or ethnicity. The congress came close to granting women the right to vote as well. Most important, the constitution was adopted by a Congress including religious conservatives and modernist liberals. They refuted the Orientalist proposition that Islam and democracy don’t mix.

Pious Arabs who still revere the writings of Rashid Rida may be surprised to know that before colonization polarized politics, he agreed to disestablish Islam as a state religion, in favor of Islamic principles of equality and public interest. The monarch, King Faisal, was elected by the Congress and pledged an oath to uphold the constitution and “religious laws,” not Islam.

As Rida argued, non-Muslims would not be equal if the state and its laws were based on Islam. Nonetheless, he argued, the resulting constitution was a state based upon Islamic principles.

The current regime in Syria must heed the lessons of 1920, which expressed political consensus based on the country’s indigenous traditions. Sectarianism – and indeed, Islamism– grew in response to foreign, Christian occupation. It was perhaps a necessary, reactionary phase. But it contributed to political instability that weakened Syria in the mid-20th century, leaving it vulnerable to foreign interference and dictatorship.

International intervention was then, as it is now, a threat to Syrian society. But Syrians in 1920 met that threat by uniting. Syrians must do the same today if they wish to put the violence of the colonial and Baathist past behind them.

In your writings, you argue that international intervention often reproduces authoritarian structures. What risks do you foresee today that could cause this pattern to recur in post-liberation Syria?

Under the French mandate, Syrian political life was deformed by foreign support for some interests against others. To impose their will, foreigners align with those who can repress resistance sectarian religious leaders, powerful economic leaders and landowners, and tribal elements.

In other words, colonizers were able to occupy and oppress societies around the world by dividing them according to class, religion, and ethnicity. Syrians must be careful today, as in 1920, that those who offer aid will repeat these tried-and-true tactics.

In your scholarly experience, where does the constitutional project typically falter in the Arab world: in the legislative texts or in the balance of power? How does this apply to the current Syrian moment?

Constitutions have failed where they have been imposed from above and outside by elites and by technocratic outsiders.

I find much wisdom in the writing of Nathan Brown on errors made in Iraq after the American invasion of 2003. There, and in other historical cases, a small elite in collaboration with outside experts engineered a document to which normal people had no allegiance.

A constitution is sustainable when it is written as a product of debate, discussion and compromise. That way, all parties in the society have “buy in”. That said, a constitution cannot be sustained if powerful forces, aligned with the military oppose it.

A prerequisite for establishing a constitutional system is the subordination of the military to civilian control and to checks and balances that prevent the executive’s unilateral deployment. Sadly, these conditions did not hold in other Arab countries after 2011. Sadly, after 250 years, they are being undermined in my own country

Today, Syrians have the chance to get it right. But the challenges are formidable. The population is in desperate, immediate need of assistance. Space for open political debate has been diminished by decades of tyranny and war. The educated, middle classes have been dispersed.

They are essential to political development, but they cannot find homes or jobs. This vacuum, and the social emergency, might tempt the regime to short-circuit the process of constitutional debate. That would be a mistake in the long run.

What lessons can Syria draw today from the history of Arab constitutionalism from the 19th century to the Arab Spring particularly regarding the separation of powers and the establishment of civilian oversight over the military?

Syrians must restore and take pride in their own history. In 1920, and again in the 1950s, Syria was a beacon of Arab democracy. Syria did not have as large a landed oligarchy as Egypt and Iraq did. Syrians had developed in Ottoman times a political tradition of tolerance and relative egalitarianism.

After World War I, it had resisted the sectarianism that disastrously undermined Lebanon. It is essential that Syrian schools and the press recall this proud tradition. Syria can and should again become a leader in Arab democracy.

You write often about historical alliances between conservative and liberal movements. Do you see the possibility for the birth of a new social alliance in Syria between the civil, Islamist, and nationalist currents to rebuild the state? What can be learned from the lessons of the past?

Syrians must reject the lies told by the Asad regime that they are a fundamentally divided people. I studied under one of Syria’s foremost historians, Abdel Karim Rafeq. He was a Christian from Idlib, but a Syrian nationalist too. He told stories about how his mother wore a headscarf outside of church in solidarity with her Muslim neighbors.

Aside from Rashid Rida and the Congress, Syrians must also recuperate the spirit of the Arab Socialist Party of the 1940s and 1950s, led by Akram Hawrani. While he was controversial, he was also important figure in Syrian history he was a socialist from Hama whose father was a Sufi leader.

That enabled him to connect with ordinary people. He built the Arab world’s first peasant movement. He was a devoted democrat who helped to re-open Syrian politics in the mid-1950s again on the basis of uniting Syrians across religion and refusing the idea that Islam and democracy are unreconcilable.

Sadly, he fell victim to the imperialist, Cold-War politics of the 1950s. I urge Syrians to revisit his four-volume memoir. It reveals in rich detail the popular, democratic, and tolerant political culture that runs deep in Syrian history.

How can Syrian society, with its diverse components, transcend the narratives of fragmentation and the antagonistic identities that the Assad regime has sowed over the course of 50 years?

This is an important question, and an essential challenge for political leaders today. I urge the ministry of education to revamp and enrich Syrian students’ study of their own history, to offer an alternative view of their society. I would urge Syrians to produce historical films and television shows, too. I dream that someone might make a television series about the 1920 Congress!

In your writings on gender and citizenship, you have long emphasized the impact of women’s participation in building the modern state. How do you view the role of Syrian women today in this foundational phase?

Furthermore, what risks do states face when they exclude women from the process of drafting the constitution and shaping new policies?

Women were so important to the democratic moments of 1920 and the 1950s in Syria. I was saddened to find, when I first visited Syria in the 1990s, how the Asad regime had disempowered women. And yet, I was heartened by all the smart, motivated, and patriotic women I met, who worked in the government, in education and as writers. Some of the most inspiring stories about the Syrian revolt against the Asads were written by women.

I cannot see how an egalitarian regime can be built upon the repression of their spirit and talent. Should Syria (as I hope) find a way of reconciling with the Kurdish movements of the northeast, I would hope that the liberation of women there might become an example. It is simply a lie to claim that religion requires women to be excluded from the public sphere. Indeed, the subjugation of any group women, or Kurds, or Christians– erodes the stability of any egalitarian, democratic regime.

You documented how France and Britain used the ‘protection of minorities’ card as a Trojan horse to justify the Mandate and dismantle the nascent Syrian state. How did this political exploitation of minorities in the 1920s impact the political sectarianism we see today in Lebanon and Syria?

The pretense that minorities need foreign protection was a widespread colonialist tactic a century ago. Its influence was most destructive in designing a sectarian regime in Lebanon. Syrian leaders refused to adopt anything like the 1926 Lebanese constitution.

In the mandate era and through the 1950s they resisted any attempt to institutionalize sectarianism. Sadly, the 1950 constitution included language basing law on Islam. This lit a flame under a powder keg. It forced non-Muslims to align with anti-democratic forces. It must be resisted today.

Likewise, the exclusion of Kurds in the 1960s violated the very principle of inclusion and tolerance established in the 1920 constitution. Syrian historians and scholars must spread knowledge of the colonial origins of sectarianism and demonstrate the prior Syrian tradition of tolerance.

If we assume the League of Nations had respected the King-Crane Commission’s report and allowed the Syrian Kingdom to endure, how do you imagine the Middle East’s political landscape would look today? Could we have avoided the rise of military dictatorships?

Historians resist counterfactualism. Yet, one cannot avoid thinking about how, if the Syrian Congress of 1920 had not been abolished, how different the Middle East would look. The expulsion of Syria from the rights-bearing family of nations, all members of the League of Nations, was deeply dehumanizing.

In Syria and elsewhere in the colonial world, this exclusion inspired anti-Western and often militant movements that spread violence. Had the Great Powers in 1919 recognized that inclusive democracy was a route to world peace, we would not have suffered decades of violence and war against colonialism in the later 20th century. This is the topic of the book I am now writing.

As a scholar who has spent years studying the early Syrian experience in constitutional governance, which historical moment do you feel most resembles the Syrian moment today?

This moment is unique. History does not repeat itself. However, this is a moment of potential democratic transition such as Syrians witnessed in 1920 and the 1950s. The problem, in both prior cases, was the defense of national sovereignty. Today, unlike 1920, Syria is not seen as a prize in the expansion of empire.

And unlike the 1950s, Syria is not a Cold-War battleground between socialism and capitalism. Precisely because Syria offers no intrinsic interest to Great Powers, it might be free to enact true self-determination.

The main obstacle to this will be the need for reconstruction funds from outside, which may come with strings attached. The Syrian government must remain extremely wary of these.

If you had to summarize the past century in a single sentence as advice for Syrians today, what would it be?

Syria is no longer a political football tossed between regional or world powers, so it has the chance now to unite in establishing a truly inclusive, just government that serves its own peoples’ best interest.

This is the second in a series of written interviews I am conducting with Western scholars and intellectuals whose academic or intellectual contributions have offered valuable insights into issues concerning our Arab region or explored Arab–Western relations. The series seeks, above all, to better understand how our region is perceived within the Western intellectual sphere.