The question of whether Syria qualifies as a “resource-rich country” has sparked ongoing debate across economic and public spheres alike. While Syria indeed possesses a diverse range of natural resources, a deeper economic analysis is required to understand what “resource richness” truly means and what factors determine a country’s ability to convert these resources into real financial value.

By examining production data, revenues, and consumption figures objectively, it becomes possible to assess Syria’s actual position relative to rentier states, and to form a clear picture of its economic prospects.

Natural Resources and the Population Factor

In public discourse, the term “resource-rich country” is often misunderstood and reduced to merely having oil, gas, or mineral reserves. In economic terms, however, resource wealth is not defined by what lies underground but by the market value these resources can generate when extracted and sold. A natural resource only becomes valuable if there is global demand for it and if it can be sold at a price significantly higher than its production cost.

Even this factor alone, however, does not suffice to classify a country as resource-rich. Economically, what matters is not the absolute value of the resource, but its per capita share the resource income relative to population size and financial needs. A resource that generates substantial revenue in a sparsely populated country may be entirely insufficient for a nation with a large population.

Thus, the notion of resource richness hinges on a balance between two elements: the realizable market value of a country’s resources and the population size it needs to support. The higher the market value and the smaller the population, the greater the state’s capacity to fund its expenditures using those resources.

This is what enables countries like Qatar or Kuwait to finance their governments almost entirely through oil and gas revenues despite having smaller reserves than other nations with far larger populations.

On the other hand, a country may have diverse and even valuable resources but still not be considered resource-rich if the market value generated per capita is too low to meet public spending needs through natural resources alone.

Diverse Resources, But Limited Abundance

A look at Syria’s natural resources prior to 2011 offers a detailed picture of its oil, gas, phosphate, and agricultural sectors not just in terms of their presence, but their actual market value.

By analyzing production, consumption, and net revenue, one can understand the real role each resource played in supporting the Syrian economy at that time.

These figures form the necessary foundation to evaluate whether Syria can compete or build a rentier economy comparable to resource-rich states.

Oil: Capacity and Revenues

Before 2011, Syria’s oil sector operated near its natural capacity and served as a major pillar of the national economy. Proven reserves stood at about 2.4 billion barrels, which, based on a price of $58.5 per barrel, equates to a present-day value of $140.4 billion.

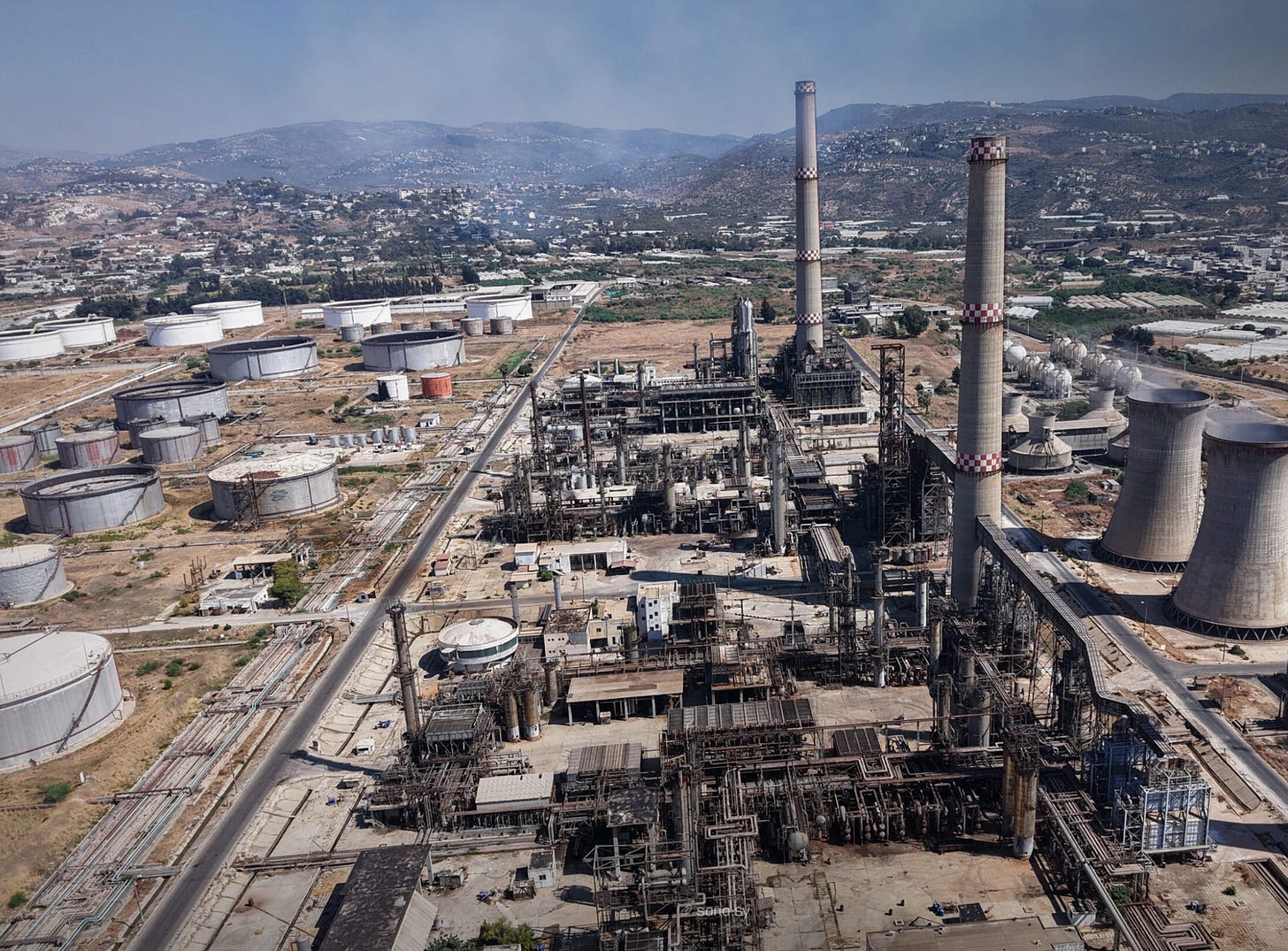

Production averaged roughly 350,000 barrels per day or 127.75 million barrels annually with a market value close to $7.47 billion. Of this, around 200,000 barrels per day were refined domestically in the Homs and Baniyas refineries to supply the local market with gasoline, diesel, and fuel oil. This allowed Syria to export about 150,000 barrels daily generating an annual revenue of around $3.2 billion.

Domestic consumption, however, hovered at 300,000 barrels per day, necessitating the import of about 70,000 barrels daily due to limited refinery capacity. At the same price, this translated to an annual import bill of approximately $1.49 billion. The net annual oil income was thus around $1.71 billion, highlighting the sector’s vital role before the conflict.

Gas: Reserves and Revenue Potential

Natural gas also played a key role in Syria’s energy structure, complementing oil. Proven gas reserves were estimated at 240 billion cubic meters, with a market value of around $72 billion at an assumed price of $0.30 per cubic meter.

Syria produced about 30 million cubic meters of gas per day roughly 10.95 billion cubic meters annually with an estimated yearly value of $3.285 billion. Of this, domestic consumption was around 18 million cubic meters per day (6.57 billion annually), valued at $2 billion.

The exportable surplus around 12 million cubic meters per day amounted to 4.38 billion cubic meters annually, generating approximately $1.314 billion in yearly export revenues.

Phosphate: Vast Reserves, Underused Potential

Syria holds substantial phosphate reserves exceeding 1.8 billion tons, valued at about $234 billion based on a price of $130 per ton.

Annual production before 2011 was around 3.5 million tons, with only 600,000 tons used domestically. The country still had to import 40% of its fertilizer needs reflecting weak local manufacturing capabilities.

Nearly the entire phosphate output was exported in 2010, yielding about $455 million in revenue. Current plans aim to raise production to 6 million tons by 2026 and 10 million tons by 2027, potentially generating up to $1.3 billion annually, with markets such as China and India being key targets.

Agriculture: A Foundational Sector with Export Power

Before 2011, agriculture was a cornerstone of the Syrian economy, contributing about 17.6% to the country’s GDP in 2010 a testament to its role in employment, income generation, and economic activity.

In foreign trade, agriculture was crucial in supporting the balance of payments. Agricultural exports accounted for about 30% of total Syrian exports. With overall exports valued at roughly $8.8 billion in 2010, agricultural exports brought in around $2.6 billion annually.

This made agriculture not only a vital source of hard currency but also key to food security and rural employment a strategic sector that could serve as a foundation for future economic recovery.

The Numbers: A Non-Rentier Reality

These data points reveal that, despite their significance, Syria’s natural resources before 2011 lacked both the volume and market value to underpin a rentier economy. Combined net revenues from oil and gas amounted to no more than $3 billion annually, while phosphate and agricultural exports added only a few billion more placing total resource-driven income at about $6–7 billion per year.

Syria vs. the Gulf: An Unbridgeable Gap?

The stark contrast between Syria’s and the Gulf’s resources becomes evident when comparing production value per capita the key metric in assessing whether natural resources can fund a state’s budget.

Even with diverse resources, Syria’s output, value, and population size prevent it from following a Gulf-style rentier model.

In Saudi Arabia, with a population of 35 million, oil revenues in 2024 reached $223.3 billion — or roughly $6,400 per person. This is thanks to the Kingdom’s capacity to produce 3.277 billion barrels per year, backed by massive reserves of 259 billion barrels sold at high global prices. Oil alone covers Saudi Arabia’s government spending and produces significant fiscal surpluses.

Qatar, with just 3.3 million people, earned $132 billion from gas in 2024 about $40,000 per capita based on its vast reserves of 843 trillion cubic feet and annual production of 179.5 billion cubic meters.

By contrast, Syria’s oil and gas revenues before the war stood at $1.71 billion and $1.31 billion respectively, with phosphate adding $455 million and agriculture contributing $2.6 billion. Altogether, these resources generated under $7 billion an amount insufficient to cover the needs of a country with 20–22 million people, giving Syrians less than $300–350 per capita annually from all natural resources combined.

That figure is a far cry from the thousands or tens of thousands seen in the Gulf underscoring why Gulf states can fully fund their budgets through resources, while Syria, due to the nature and value of its resources and population size, cannot.

The core difference is not about having resources but about the wealth they generate per person. Gulf resources are high-value, high-yield, and low-cost. Syria’s, by contrast, are modest in value, limited in output, and unable to produce the necessary revenues to fund a large state budget.

Can Syria Fund Itself Through Resource Revenues?

A review of Syria’s 2010 state budget which stood at $16.55 billion shows just how limited the role of natural resources was, even in peacetime. Oil, gas, and phosphate revenues together did not exceed $4.3 billion annually, covering only about 26% of the total budget. The government thus had to rely heavily on taxes and other revenues to meet its obligations, demonstrating that Syria never operated a true rentier model.

The contrast grows sharper when comparing with oil states. In 2024, Saudi Arabia’s total revenues reached 1.259 trillion riyals ($335.7 billion), of which 756.62 billion riyals ($201.7 billion) came from oil alone more than 12 times Syria’s entire 2010 budget helping fund government spending that exceeds $366 billion.

In Qatar, projected 2024 revenues were 202 billion riyals ($55.48 billion), with $43.67 billion from oil and gas. These figures vastly outstrip Syria’s total resource income and allow Doha to fund nearly all of its $55.18 billion in spending.

In this context, it becomes clear that Syria’s challenge lies not only in the quantity of resources it holds, but in their limited market value and inability to match the needs of a sizeable population. While Saudi Arabia and Qatar fund most of their spending through energy exports, Syria even in its most stable years lacked the structural capacity to do so.

This proves that Syria’s future economic model cannot rely on natural resources alone, as some might imagine.

Toward a New Economic Model: Investing in People

Syria’s economic experience shows that natural resources despite their importance lack the market power and scalability to sustain a population-rich country. As such, they cannot serve as the cornerstone for a sustainable development strategy.

The urgent task now is to transition toward a new economic model based on human and knowledge capital the most renewable and scalable resource available.

This alternative model calls for major investments in education, research, technology, digital skills, and innovation. As seen in the experiences of South Korea and Singapore, countries can become economic powerhouses even without abundant natural resources.

To make this possible, Syria must improve its business climate, attract investment, and develop infrastructure especially in energy, transport, and communications. This would open space for high-potential sectors such as pharmaceuticals, IT, agro-industries, cultural and medical tourism, and specialized agriculture.

This transformation also requires modern fiscal policies: operating budgets should be funded by stable, predictable revenues such as taxes, while resource-based revenues which are volatile and exhaustible should be directed toward long-term investments like rebuilding infrastructure and improving the business environment.

Such a distinction between revenue types can protect public finances from volatility and lay the groundwork for a productive economy built on value creation through knowledge and skills not simply resource extraction.

In this vision, Syria’s real wealth lies not in oil or gas, but in its people.