A long history of interventions and geopolitical entanglements has shaped U.S.–Iran relations, culminating in the current state of open hostility between the two nations. This enmity has become a convenient backdrop for both governments to hang their foreign policies on—not only in terms of their bilateral dealings but across the broader Middle East.

It even goes further to form the underlying framework for opposing alliances and blocs in the global order, where both nations stand at ideological and strategic extremes, challenging the unipolar dominance that emerged after the Soviet Union’s collapse.

Although much of the historical and political literature dates the modern U.S.–Iranian tension to the 1979 Khomeini-led revolution, the roots of hostility run deeper—specifically to the post-World War II period. At that time, the United States and its Western European allies were basking in their victory and attempting to shape a new world order aligned with their interests and regional ambitions.

In our "Memory of Hostility" file, we trace the tumultuous trajectory of U.S.–Iran relations—how hostility became the organizing principle of U.S. policy in the Middle East, justifying arms races, military alliances, and economic sanctions. We also attempt to assess the future of this fraught relationship amid shifting regional and global dynamics.

The Shah and the Supreme Leader: Early Signs of Crisis

At the end of World War II, the Western bloc led by the United States celebrated a political and economic triumph, but its challenges were far from over. Trouble began the very night the Soviet Union signed its surrender in Berlin on May 8, 1945.

As the U.S. and its European allies worked to secure their interests in the East—especially in oil trade—a wave of anti-colonial rebellion swept through their territories. Socialist and communist ideologies began taking root across the region.

The Soviet Union played in the shadows, offering what colonized nations desperately sought: liberation and the right to self-determination, free from the interests of a West that had exploited their resources.

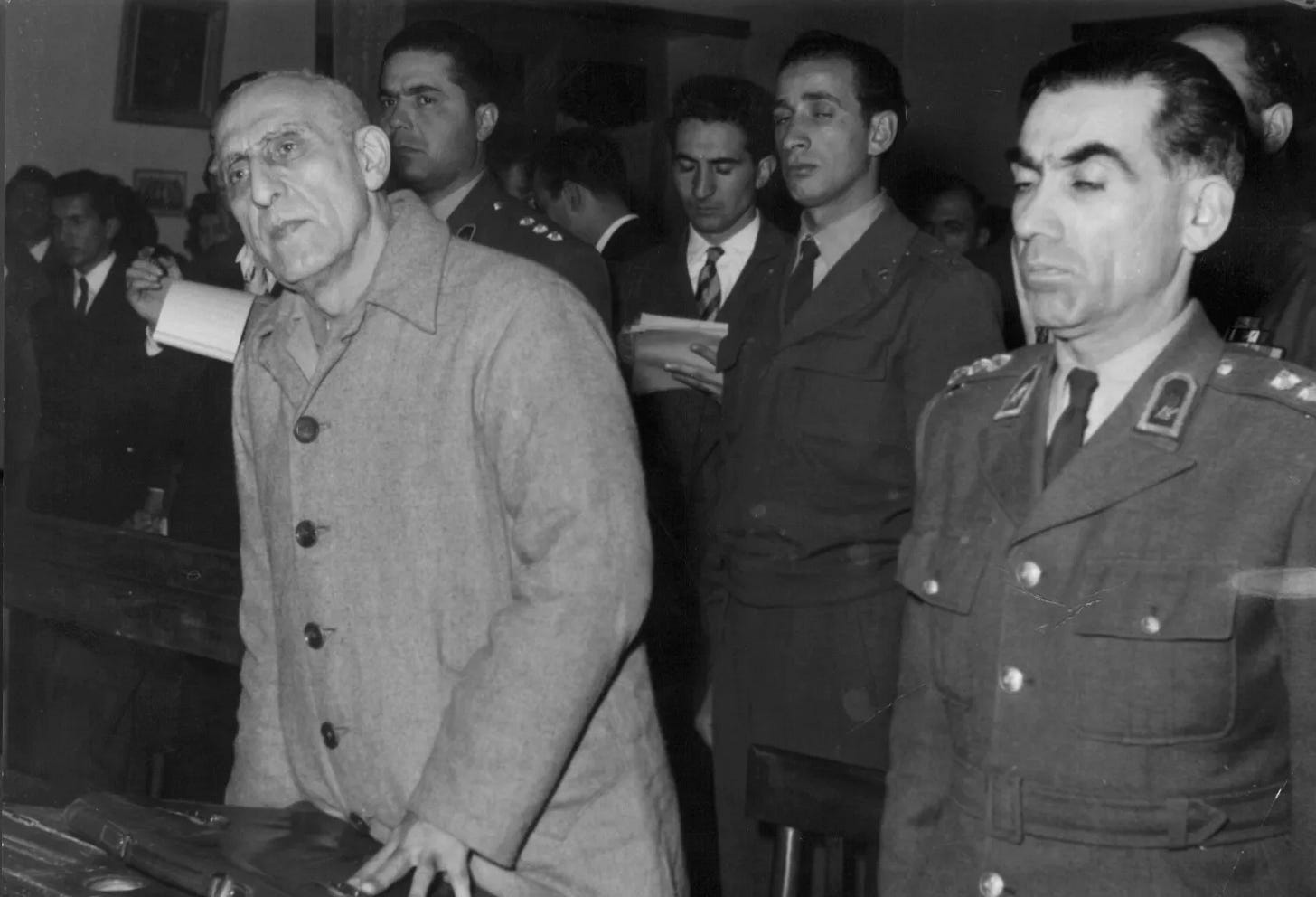

Iran was no exception. The democratically elected government of Mohammad Mosaddegh (1951–1953) showed signs of aligning with socialist thought, alarming the U.S. and the UK, which viewed this as a direct threat to their oil interests. The result: a jointly orchestrated coup in 1953 that reinstalled the pro-Western Shah.

At the time, Britain controlled Iran’s most important oil company, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), reaping most of the profits while Iranians received little benefit. Once it became clear that Mosaddegh sought to nationalize the oil industry for Iran’s benefit, the CIA and British intelligence intervened to overthrow him and restore Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The Shah emerged as a key Western pawn in the region and a staunch U.S. ally in the Cold War. Washington rewarded him with military and economic support, enabling him to modernize Iran’s armed forces and even pursue an early nuclear program backed by the West.

However, the Shah’s authoritarian rule and open allegiance to Washington created fertile ground for radical change. This came in the form of Ayatollah Khomeini, who rose to power following a U.S.-backed regime collapse.

Khomeini's rise signaled further troubles—not only because of his open hostility toward the West and anti-imperialist agenda but because he led an expansionist ideological project that directly challenged Western dominance. Thus, 1979 marked the beginning of a new chapter in U.S.–Iranian hostility that would cast a long shadow over the region.

The U.S. quickly seized on Khomeini’s doctrine of "Wilayat al-Faqih" (Guardianship of the Jurist), branding it a theocratic ideology at odds with American ideals of civil rights and democracy. Washington used this to frame Iran as a threat, though the underlying conflict was more about influence and power than ideology.

The Hostage Crisis and the Birth of the 'Terror' Label

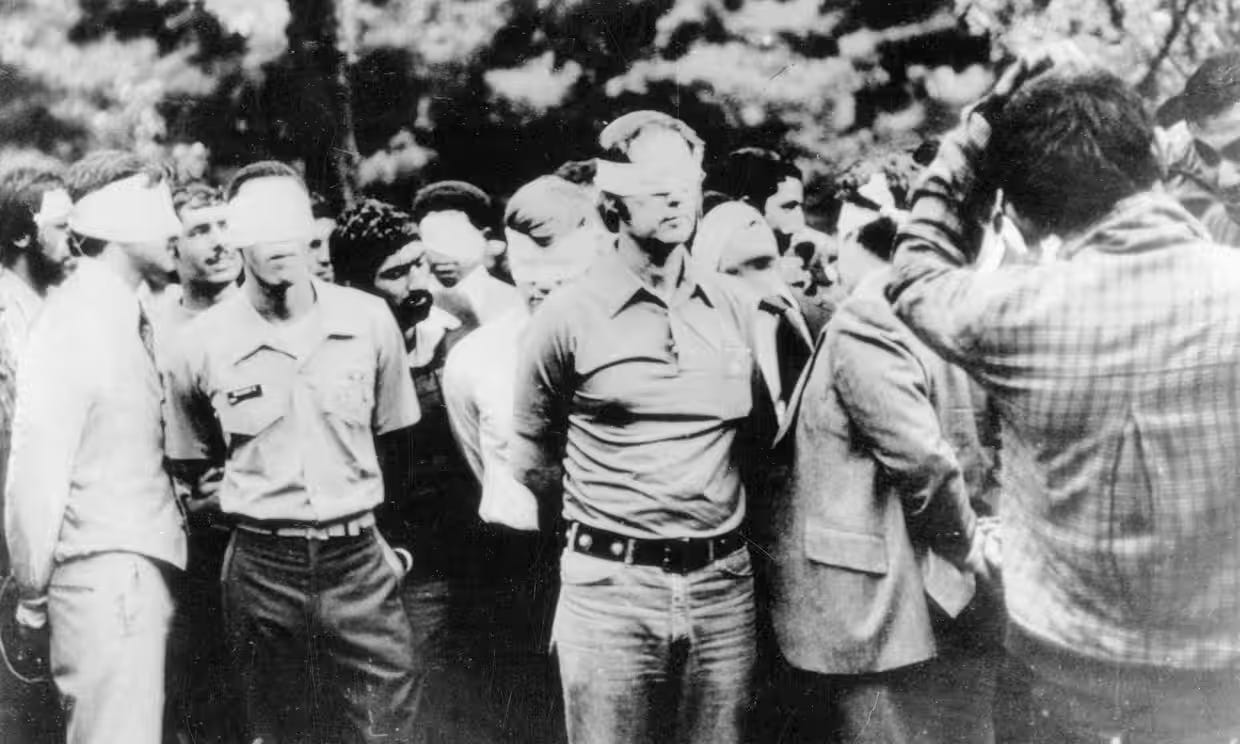

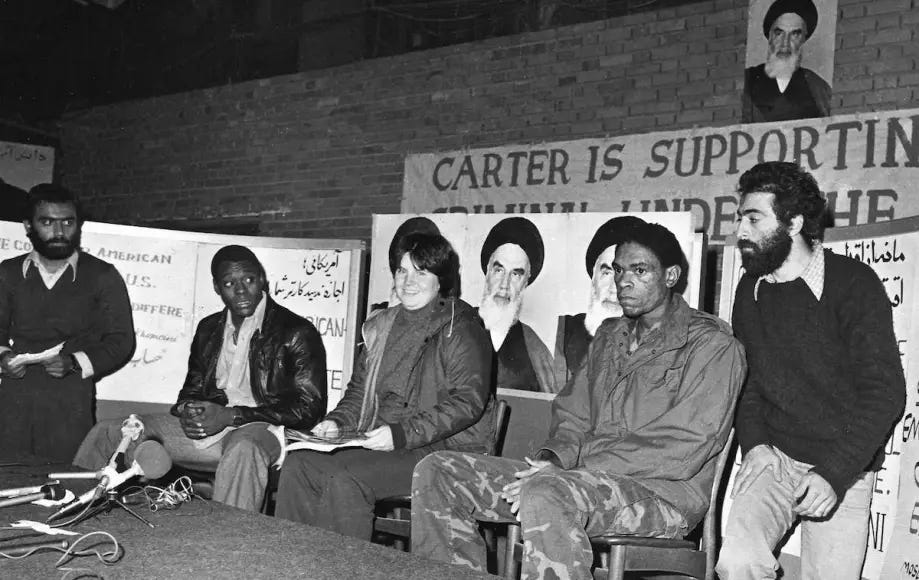

Khomeini’s anti-American rhetoric quickly bore fruit. In November 1979, Iranian students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage, demanding the return of the Shah from U.S. asylum to stand trial in Iran.

The 444-day hostage crisis defined President Carter’s foreign policy, especially toward ideologically hostile regimes in the Middle East. Diplomatic ties were severed, and a prolonged cold war began between Tehran and Washington. The crisis marked the end of formal diplomatic relations.

It also ushered in a new era of U.S. sanctions and laid the foundation for Washington’s war on terror. Carter signed Executive Order 12170, freezing $12 billion of Iranian assets—an unprecedented use of presidential powers under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

Today, at least seven executive orders remain in effect against Iran, targeting its military, nuclear programs, and regional militias, as well as internal human rights violations.

Though Carter tried to internationalize the sanctions at the UN in late 1979, the Soviet Union vetoed the effort, viewing Iran as a useful counterweight to the U.S. Other countries, including China and revolutionary allies like Mexico, also opposed U.S. moves, while some European nations (Austria, Sweden, Poland) strengthened trade ties with Iran.

On the other side, Washington assembled a coalition to isolate Tehran. Portugal, Japan, Australia, and most Western European countries reduced or severed economic and diplomatic ties with Iran.

The economic toll was immense: U.S. exports to Iran plummeted from $3.7 billion to $23 million in one year. Imports dropped from $2.9 billion to $458 million. Allied sanctions cost Iran $3.3 billion in losses between 1980 and 1981.

Though the crisis ended with an agreement in January 1981, the damage was lasting. The U.S. learned that Iran could be pressured into negotiations, while Iran learned not to trust Washington with its assets.

The First Gulf War: Playing Both Sides

U.S. involvement in the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), in which up to a million people were killed, further entrenched the bilateral hostility.

Though officially neutral, the U.S. gradually tilted toward Saddam Hussein, whose war aimed to punish Iran for its support of Kurdish rebels and territorial claims over the Shatt al-Arab. Washington provided Iraq with military intelligence—and possibly even chemical weapons precursors.

Internal memos from the Reagan administration, particularly to Secretary of State George Shultz, hinted at U.S. complicity in Iraq’s chemical warfare campaign. Reagan’s national security policy ignored or downplayed Iraq’s violations of the Geneva Protocol.

The U.S. also sent envoy Donald Rumsfeld to reassure Saddam of shared interests. Only after a U.S. company was found to have sold 22,000 pounds of phosphorus fluoride—a chemical weapon precursor—did the administration condemn Iraq’s use of such weapons.

Even as it backed Saddam, the Reagan administration secretly sold arms to Iran in the infamous 1985 Iran–Contra Affair, revealed in 1986. The arms deal, worth $30 million, violated congressional bans. Only $12 million showed up in official records. The administration later claimed it aimed to rescue American hostages in Lebanon, though it also used the funds to support Contra rebels in Nicaragua.

This duplicitous strategy prolonged the conflict and weakened both Iran and Iraq, while boosting America’s Gulf influence. Diplomatically, Washington’s internal divide meant some policymakers saw Iran as a lesser evil and aimed to prevent a decisive victory by either side.

Proxy Wars and Iran’s Regional Reach

Iran’s growing influence via proxies in the Middle East and Arabian Peninsula has strained its ties with Washington. These groups challenged U.S. authority while giving Iran deniability for regional attacks.

Tensions escalated through a series of deadly assaults: Hezbollah’s 1983 bombings in Beirut that killed over 300 Americans; the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia; hundreds of attacks in Iraq by groups like Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and Kata’ib Hezbollah; and ongoing Houthi strikes on U.S. interests in the Red Sea.

Washington’s policy has varied: labeling some groups terrorists, like Hezbollah; engaging others diplomatically, like the Houthis (briefly delisted under Biden); and even coordinating militarily with others, like Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces against ISIS.

The October 7, 2023 Hamas-led attack and ensuing regional escalation—including Israel’s confrontation with Iran—further consolidated U.S. antagonism toward Iranian proxies. Despite their varying levels of autonomy, Washington views them as extensions of Iran’s Quds Force, especially Hezbollah and the Houthis, whose weapons and air defense systems resemble those of Iran’s IRGC.

Breaking Free and the Nuclear Crisis

The late 1990s saw renewed fears over Iran’s nuclear ambitions, allegedly aided by Pakistan and China. By the early 2000s, revelations about Arak’s heavy-water reactor and the Natanz enrichment site sparked global concern.

Though Iran’s nuclear program originated under the Shah with U.S. support, it was suspended post-1979 and later damaged during the Iran–Iraq War. Tehran resumed efforts in the 1990s, insisting on peaceful intentions while secretly continuing uranium enrichment.

In 2007, the U.S. exposed Iran’s hidden operations, leading to harsh sanctions and international pressure. Tehran stalled IAEA inspections and resisted disclosing full details of its program, prompting concerns over potential violations of the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

President Bush led efforts to contain Iran, freezing assets and sanctioning banks and individuals linked to the program. The issue was also linked to Iranian-backed violence in Iraq.

President Obama maintained sanctions between 2012 and 2014 but pivoted toward diplomacy. In 2015, the JCPOA nuclear deal was signed, imposing limits on Iran’s nuclear activity in exchange for phased sanctions relief under UN supervision.

The deal was short-lived. President Trump withdrew in 2018, launching a "maximum pressure" campaign. Iran gradually pulled out of its commitments, officially exiting in 2020 and resuming full-scale nuclear development.

Efforts by President Biden to revive negotiations have faltered, yielding only partial progress on sanctions and prisoner exchanges. Tensions have surged since Trump’s return to office, with direct U.S.–Iran clashes including strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities and retaliatory Iranian attacks on U.S. bases like Al Udeid in Qatar.

As tensions crest with opposing alliances solidifying, both Tehran and Washington stand on uncertain ground. Whether their animosity will flare into open conflict or simmer under a fragile detente remains to be seen. The coming chapter may yet reveal how far this enduring hostility will go.