After the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024, the first waves of displaced Syrians began flowing back into the liberated cities and towns. Thousands of families returned, carrying whatever belongings they could, driven by a powerful desire to reclaim what remained of their lives.

The scene was similar across many areas: destroyed homes, desolate streets, and cities weighed down by devastation, their features almost unrecognizable. Yet over the first year of liberation, the experiences of returning families revealed a deeper meaning to this homecoming one tied to belonging, memory, and the possibility of rebuilding the future.

Amid the hardships of returning, the first steps of clearing rubble and restoring homes, the efforts to reestablish daily routines, and the struggles to overcome adversity, Syrians demonstrated a profound ability to turn ruin into a new beginning. They began, with their own hands, to forge a new reality, despite the immense pressures they faced every day.

This report documents testimonies from returnees and sheds light on grassroots efforts to reopen homes and restore what can be restored, even in the absence of sufficient support.

Amid the scenes of destruction and the earliest signs of revival, the Syrian people’s determination to reclaim their lives stands out despite the crushing conditions and the weight of accumulated challenges.

Caravans of Return: When Longing Prevails

In the early hours following the liberation of Damascus on December 8, 2024, the movement of displaced Syrians returning to their hometowns accelerated remarkably. Families began preparing to return, even though their homes remained in ruins and the roads were far from safe.

For many, this return was a declaration of their unwavering attachment to the land and a desire to end years of uprooting and displacement.

On the first day after the capital’s liberation, families began collecting whatever items they could, responding to an inner drive that overpowered all obstacles. In the following days, practical preparations began: organizing group transportation, coordinating travel with neighbors and relatives, contacting those who had already returned to liberated areas, and assembling basic necessities like blankets and simple cookware.

Soon, organized caravans began making their way from Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and northern Syria. Some returnees in Lebanon even took unmarked mountain routes to cross the border, unwilling to wait for official convoys and choosing to risk treacherous paths to reach their homes.

These caravans included modest vehicles and families carrying what little they could. The tears of mothers mixed with children’s laughter, and the Syrian flag was raised amid chants of “Allahu Akbar.” This return was a communal experience a reuniting of a fragmented society.

There was unmistakable joy on the faces of those returning. Tears and smiles mingled, reflecting a mix of longing, pain, and hope. There were powerful scenes: an elderly man weeping with joy despite knowing his home was destroyed, a woman overwhelmed by memories, and children laughing simply because they were “going back to their country.”

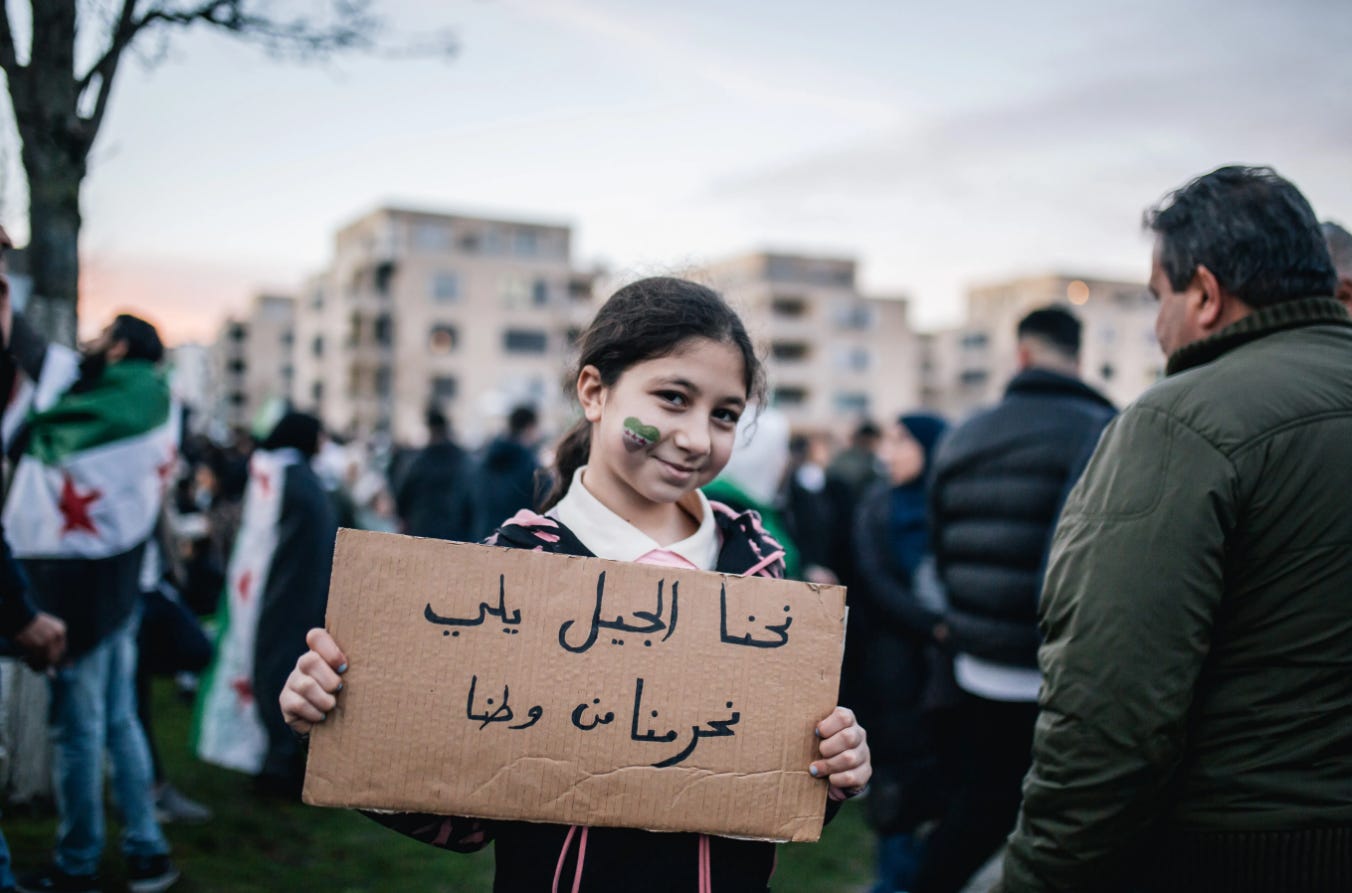

For children who had only known Syria through stories and pictures, this was the beginning of their own journey of discovery.

These scenes carry profound meaning. Tents, hunger, and cold had not broken people’s spirits; their emotional bond to place remained unshaken. Returning wasn’t just about having a roof overhead it was about reclaiming identity.

As one mother who returned with her three children said, “I’d rather live in a tent in my homeland than enjoy comfort in exile. That’s my belief.”

The return of a caravan to the town of Kafr Nabudah after more than 12 years of displacement exemplifies this on the ground. Their testimonies echoed words like dignity, honor, beloved homeland, memories, hope, patience, tears, and grief.

The decision to return was not material it was emotional, rooted in identity and memory, a bid to restore ties severed by long years of war.

The First Return: A Collision of Shock and Hope

From the moment cities and villages were liberated, caravans of returnees began arriving one after another. The first return was a mix of shock and hope: homes without roofs, crumbling walls, and streets transformed beyond recognition.

In the early days, some families pitched tents atop the ruins of their homes. Others began repairing whatever rooms they could salvage. A recurring phrase among returnees was both painful and resolute: “We came back from the tents to the tents.” One returnee summed up the spirit of the moment: “Our house is destroyed, but thank God we’re back in our country, and we will rebuild our lives from scratch.”

Testimonies from returnees express a range of emotions nostalgia, hope, and shock. Children discovered their homeland for the first time with wide-eyed wonder, while adults faced the harsh reality of destruction. And yet, they also felt they were recovering part of themselves.

Umm Abbas, who returned to her hometown in Daraa after 12 years, said, “I was happy when I arrived, but I was shocked by the state of the country. My hope is that God will allow Syria to be rebuilt from scratch.”

Videos of the return show deep emotional loss. In one, journalist Sarah Kazem returns to her home in Homs and says: “They stole our lives from this house.” Her words speak not of broken bricks, but of the severed ties that once shaped an entire life.

Returning wasn’t just about visiting ruins it was about piecing together what remains of the self and salvaging a threatened sense of meaning.

Scenes of return paint a vivid picture of joy clashing with devastation. The thrill of coming home is often tempered by the harsh reality. An engineer returning to his village of Tal Mardikh found streets unrecognizable, houses stripped of their identity, and destruction etched into every corner. The long disconnect from the land turns the joy of return into a deep shock but also awakens a fierce desire to rebuild.

Returnees from Lebanon faced mixed emotions yearning laced with anxiety. After years of adapting to life in exile, uncertainty about the future loomed large. Yet the longing to return to the “embrace of the homeland” outweighed their fears.

This emotional tension is central to the return experience a complex mix of hope, concern, and identity.

Many returnees were resolute: they wouldn’t wait for international aid. Rebuilding their villages was their responsibility. For them, return wasn’t just about geography it was a journey into memory and origin. Syrians weren’t coming back to claim destroyed houses; they were reclaiming parts of their identity.

One man from Homs said, “I left Syria as a child and grew up in Lebanon, but my kids will adapt better here in their own country, with their school and their future. This is their home.”

In a video documenting the return of Chef Omar and his wife after 13 years of displacement, the emotional bond to place is palpable. The journey starts on the road to his old neighborhood, passing familiar yet altered sites, and culminates in a wave of disorientation and grief amid the wreckage.

But when old neighbors and friends begin to gather, the experience shifts from personal to collective memory reaching its peak when he reenters the house, where tears and flashbacks collide.

Tears of joy soften the trauma of the past, but do not erase the daily challenges of return. These testimonies show that returning is not a simple act—it’s an emotional and social transformation, filled with nostalgia, belonging, and the looming burden of uncertainty.

The repeated phrases in videos like “Alhamdulillah” and “May God have mercy on Syria’s martyrs” reflect the sincerity and depth of connection to the land, and the resilience needed to adjust to a country that has lost its former shape.

In one case, a girl returned to her old street after 13 years. She couldn’t recognize her home its familiar doors gone, cracked walls and shattered tiles telling the story of destruction. With a trembling hand, she filmed every corner and called her father via video, hoping he could recognize what remained of their building.

Abdul Rahman al-Tayyib returned to Damascus to revisit childhood landmarks his grandparents’ house, the balcony, the school bus stop reconnecting with the cultural and familial roots he had grown up with. Meanwhile, Abu Khaled returned to his city and neighborhood after years away. His eyes scanned the ruined buildings and battered streets.

With each step, nostalgia crept in memories of his old home, the scent of the street, corners that held echoes of his youth. He stood at the crossroads of past and present: the joy of return intertwined with the grief of loss.

This collision between memory and reality is deeply painful, but it also sparks a drive to rebuild not just homes, but identity and life itself.

How Families Rebuilt Their Homes

Following December 2024, the return journey to liberated towns and cities was as much about confronting memories as facing devastation. Returnees had to accept temporary homes, scarce resources, and persistent environmental dangers—requiring immense psychological resilience.

They were met with a tragic reality: destroyed homes, blocked roads, collapsed infrastructure, and the lingering threat of landmines and unexploded ordnance. Yet their return was an act of resistance a declaration that life could go on, even in the face of ruin.

As families arrived in their hometowns, they began rebuilding, often entirely through their own efforts. With little to no access to essential services, most found their homes badly damaged or uninhabitable, forcing them to live in partially destroyed structures. Community-led initiatives helped clear rubble, reopen roads, and revive small-scale economic activity.

There was no meaningful state support. Residents depended on personal initiatives and unofficial aid including financial help from relatives abroad. The first step was always rubble removal a grueling task, often done with minimal equipment. But these grassroots efforts signaled Syrians’ determination to breathe life back into their homes, regardless of the magnitude of destruction.

With limited tools and materials, many families began with a single livable room and expanded it over time. Individual efforts emerged, such as engineer Abdul Aziz’s project to map damaged yet salvageable homes to present to relevant agencies. Local leaders also played a role in easing the return and organizing rebuilding efforts.

Civil society groups like Unsar applied a “revivable zone” approach restoring a cluster of homes, schools, wells, and basic services, and supporting agriculture and livelihoods. Still, the scale of devastation made these efforts akin to first aid for a body with multiple wounds.

Some families used temporary fixes covering broken roofs or pitching tents over ruins. Others began rebuilding with salvaged bricks, sometimes crushing rubble themselves to make building materials due to the high cost of traditional supplies.

Stories like that of Zeinab Murad reflect this spirit. She returned to the home her family fled in 2013 and began rebuilding with the bare minimum, seeking shelter for her children. “When I feel afraid,” she said, “I read the Quran and put my trust in God.

I say, ‘Lord, I entrust you with my children and my home.’” Her words capture the emotional weight of return it is not the end of hardship, but the beginning of a new chapter in survival.

Life Returns Step by Step: Harsh Challenges, Unyielding Will

In the days and weeks following the return to liberated towns after December 2024, Syrians gradually began rebuilding their daily lives amid the near-total collapse of basic infrastructure.

The crisis extended far beyond ruined homes. Power grids were destroyed, water stations out of service, schools and hospitals in rubble, roads impassable, and local economies shattered.

Still, signs of life began to emerge. A few schools reopened, albeit with difficulty. Some shops resumed operations. Simple, personal efforts were made to restart clinics and classrooms, launch micro-projects to supply bread and water building a slow, fragile rhythm of life infused with hope. Women played a central role in reestablishing emotional and social safety nets, particularly for children and families, fostering a renewed sense of stability.

But the challenges were staggering: dysfunctional sanitation systems, unaffordable utilities, and constant threats from unexploded ordnance in fields and roads.

Returnees’ video testimonies captured these realities. In Homs, Hammoud Seif documented the shock of destruction and empty streets but also the beginnings of collective efforts to revive daily life.

Another returnee noted stark inequalities between neighborhoods some clean and powered, others abandoned and without services. Standing in the dusty, suffocating air, he felt the collapse of services mirrored in every breath.

In a video of a man returning to Syria after 13 years, scenes of destruction in Jobar and Harasta blended with moments of tentative rebuilding.

Many returnees said that coming back was about reconnecting with family and community ties ruptured by exile, and grounding their children in a familiar cultural and emotional landscape.

Return was not the end of suffering, but the start of a new, challenging chapter. With no transport, unusable schools, and constant risks, Syrians clung to the hope of staying seeing their return as a reclaiming of dignity, roots, and identity, and an attempt to raise the next generation in a homeland they could call their own.

In the end, the return to liberated villages tells a story of resilience of people determined to rebuild life, from the ruins of a homeland they never stopped believing was worth returning to.