In 1918, the Zionist movement commissioned the architect Patrick Geddes to devise a comprehensive urban plan for Jerusalem, which included a detailed engineering design for the Hebrew University intended to be built on “suitable” land in the Holy City.

Geddes soon produced an architectural vision inspired by Torah symbols, combining Zionism’s ambition to establish its presence on the land of Palestine with a future-facing plan to transform the Mount of Olives into what was considered the “Temple Mount.”

That blueprint reflected a hybrid of Jewish religious heritage and the political Zionist project, positioning the establishment of the university as an initial step toward realizing the “Torah myth” as Zionists conceived it.

In this context, and under our “Civil Settlement” file, we examine another component of the Zionist network of services and support: the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Over the past century, it has played a central role in shifting the Jewish settlement project in Palestine from politics and militarization into arenas of education and culture.

Through detailed maps and plans, we review how this university established academic relationships that supported settlement and provided intellectual and cultural foundations that expanded and reinforced its presence from the years before the first ethnic cleansing in 1948 up to the present day.

No English, No Palestinian

By the end of the 19th century, the Jewish activist, rabbi, and Russian mathematician Zvi Hermann Schapira traveled across Europe propagating his vision of creating a Jewish national homeland in Palestine. While debates among European Jews swirled over the most suitable location for their future homeland, Schapira early on fixed his compass on Palestine.

He joined the Lovers of Zion movement, which was at the forefront of organizing the early Jewish immigrations to Palestine, as well as exploration campaigns aimed at preparing the ground for settlement—thus becoming one of the first to help give shape to the Zionist project in reality.

In 1882, Schapira formulated the concept of founding the Hebrew University, with the aim of creating an institution that would unite Torah and wisdom, reaching every home in “Israel.”

He presented this ambitious vision at the First Zionist Congress in 1897, where he emphasized the university’s importance in reviving Jewish culture and sciences, and in offering higher education grounded in scientific principles for Jews—believing this step would strengthen national and cultural consciousness.

Schapira viewed the founding of the university not merely as an educational project, but as a foundational pillar for building Jewish society in Palestine. He stressed that higher education would serve as an effective tool in forming a scientific and cultural elite capable of leading the Zionist project and cementing its intellectual and political presence.

Schapira’s proposal was more than a general idea. It was reinforced by a clear vision of administrative and academic structures, even the identity of students. He proposed the university be a specialized educational center in Judaic studies, seeking to enhance Jewish cultural awareness and support scientific revival.

His academic vision included multiple faculties: a faculty of Jewish history, a center for modern sciences, including medicine and engineering. As for students, he proposed that admission be limited to Jews from all over the world, and that the development of knowledge serve above all the Jewish people—the university thus becoming a symbol of their civilizational progress.

At the same congress, Schapira introduced another idea not less important than the university: the establishment of the Jewish National Fund, as a means of collecting funds from Jews worldwide via “blue collection boxes,” to buy land in Palestine, develop infrastructure for Jewish settlements, and provide a firm economic base for building a Jewish independent homeland.

One year after proposing these pioneering ideas, Schapira died of pulmonary disease. But his dream of founding the Jewish National Fund did not die, nor did his vision for establishing the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He insisted that the university be an essential part of building a strong and independent Jewish nation.

By 1913, during the 11th Zionist Congress, Zionist leaders officially adopted a resolution to proceed with establishing the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Subsequently, the World Zionist Organization purchased the plot of land where the main campus would be built—land formerly owned by British orientalist John and Caroline Emily Gray Hill, who had arrived in Palestine in the early 20th century.

The Hill couple, exploiting their ties with local landowners, acquired the land, and produced methodical documentation: “curated” photographs meant to reflect the Zionist claim “a land without a people, for a people without a land” as propagandausing a falsified history to obscure the fact of indigenous Palestinian presence.

Zionist efforts reached their peak after the British forces occupied Palestine in 1917. When General Edmund Allenby entered Jerusalem in November of that year, he imposed martial rule over the city, coinciding with the issuance of the Balfour Declaration, in which the British government declared its support for the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine giving Zionist movement huge political and diplomatic momentum to further its settlement project.

Competing Visions for Higher Education

In this climate, opposing visions emerged concerning higher education in Palestine. Sir Ronald Storrs, the British Governor of Jerusalem, sought to establish an English university that would integrate Arabs and Jews into a shared educational and cultural framework. But this idea clashed with a rigid Zionist position, led by Abraham Oseīkin, head of the Jewish National Fund, who insisted on creating a Hebrew university solely for the Zionist project.

Within a year of British rule, the Zionist movement organized an official ceremony to lay the cornerstone for the Hebrew University. Oseīkin employed his influence to persuade Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner and a prominent Zionist supporter, to recognize the Hebrew language as an official language in Palestine—providing legal and cultural cover for embedding Jewish character in Zionist institutions.

Meanwhile, as the Hebrew University’s buildings were erected and academic programs developed, the Zionist movement persisted in undermining any attempt to establish an English or Palestinian university representing the indigenous inhabitants.

Historian Ilan Pappé notes that in 1922, Storrs formed a committee including Palestinians, British, and Jews to explore establishing a “university for all”; this committee's efforts were thwarted by Zionist maneuvering, acting out of concern that any multi-identity educational institution would threaten its cultural and scholarly hegemony in Palestine.

Facing continued Zionist pressure, which insisted that any new university in Jerusalem cater only to Hebrew culture and obstruct the completion of the Hebrew University project, Storrs excluded Jews from meetings in the committee he had formed. In 1923 he instead founded an independent body called the Palestine Council of Higher Studies, aimed at crafting a practical alternative—i.e., a Palestinian university.

The Council’s mission was to plan for a Palestinian university, focusing on preparing Palestinian students for higher education. They reached out to the Director of Education in the British Education Ministry in London to design curricula and suitable courses. They also launched a “Higher Certificate” system, which was quickly recognized by major universities like the American University of Beirut (1924), Cambridge, and Oxford.

This certificate system allowed its holders to enter major universities and also prepared them to become teachers in Palestinian schools, raising the level of education in cities and rural areas alike. Yet the project for a Palestinian university remained under planning and research for years, until late 1929, when the British administration abandoned its support under political pressure and Zionist lobbying, which strove to solidify academic dominance through the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Zionism Opens Its Academic Ceremony, Arabs Protest

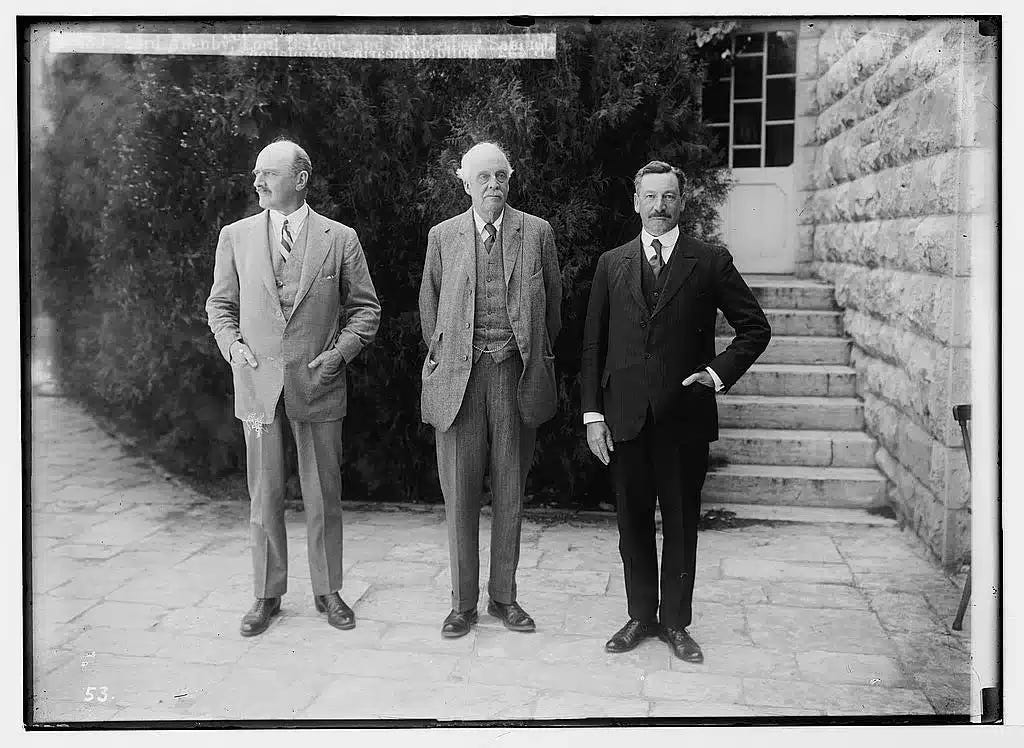

Seven years after laying the cornerstone, Zionist organizations announced the inauguration of the Hebrew University on April 1, 1925, in a large ceremony attended by prominent political and religious figures: most notably Lord Arthur James Balfour, author of the Balfour Declaration; the British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel; Zionist leaders such as Chaim Weizmann, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, and Chaim Nachman Bialik.

Strikingly, the event—a mix of cultural and political activities in Jerusalem—drew over ten thousand people under British security. Despite popular anger, a general strike declared by the Palestinian national movement, and denouncements in Palestinian newspapers (which marked the event with black frames to protest Balfour’s visit), the presence of Arab and Palestinian officials stirred controversy.

Prominent Arab figures attended: the Egyptian government’s delegate Ahmed Lutfi al-Sayed, known as “Professor of the Generation”; the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Maknas; the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Kamil al-Husayni. Taha Hussein, one of the pillars of Arab intellectual life, sent a congratulatory telegram and later visited the university, praising its academic level—a gesture that added another dimension to the debate about this university, viewed by many as part of the Zionist settlement project in Palestine.

Amid widespread Palestinian popular rejection and accusations of early academic normalization, some Palestinian notables—backed by the British—defended the participation of Arab figures in the 1925 inauguration. Among them was Haj Amin al-Husayni, who justified his attendance by saying it did not amount to acceptance of Zionist hegemony, arguing that confronting occupation requires knowledge and learning, not only protest.

Nevertheless, despite the pluralistic appearance of the opening, the Hebrew University remained a distinctly Jewish institution. Beginning with its board of governors, which included leading Zionist figures like Chaim Weizmann, Albert Einstein, Chaim Nachman Bialik, Nahum Sokolow, Yehuda Leib Magnes—and going through admission policies that restricted enrollment to Jews only, along with the requirement of Hebrew proficiency.

In its first year, the university launched three scientific institutes: the Institute of Jewish Studies; the Institute of Microbiology; and the Institute of Chemistry. Its student body comprised 141 students and over 30 professors. By the early 1930s the university had begun awarding the second academic degree.

The Nakba Excludes the Hebrew University

During its first two decades, the Hebrew University built strong academic ties with Western research circles, in spite of the mounting political unrest in Palestine. Even as World War II raged, the university strove to present itself as an institution separate from regional political tumult.

At the same time, Zionist militias continued land seizures and displacement, and academic support for the university formed part of efforts to sustain its existence and the legitimacy of its project in Palestine.

During the Nakba and the Zionist takeover of Palestinian land, the Hebrew University was forced to move its main activities from Mount Scopus, its original site, to another location in “West Jerusalem,” after Mount Scopus became difficult to access due to tense military and political conditions.

This forced relocation led to an academic decline particularly in scientific fields since the university struggled to maintain its academic standing. To compensate for losses caused by interruption of operations, Zionist leadership constructed a new campus on the ruins of the Sheikh Badr neighborhood in the Palestinian village of Lifta, which had been depopulated by Zionist forces.

This new campus was named Givat Ram, intended as a new academic center, reinforcing Zionist presence in “West Jerusalem.”

Due to strong Israeli alignment with Western communities, the early period after opening the new campus saw students and faculty arriving from around the world; new majors in science and engineering were inaugurated, contributing to its positioning as a research institution in “Israel” and within Western academia.

Meanwhile, the Hebrew University pursued a systematic erasure of all that was Arab, Palestinian, or Eastern—starting from agricultural and industrial disciplines, to engineering, urban studies, and geography. It used its scholarly output to erect a Western academic and societal reality resembling the settlers’ country of origin, denying the land’s history and place.

Nevertheless, in just a few years, the university managed to reactivate the original Mount Scopus campus. Because of its status as a civilian establishment, it enjoyed international protection, and every fortnight it received a regular supply from the Western sector: 86 policemen and 35 Israelis every two weeks, backed by international forces to ensure that the Jordanian side respected the principle of protection.

By 1953, the new Hebrew University campus had begun welcoming students and researchers. It was joined by other major institutions in “West Jerusalem,” such as the Knesset, Israel Museum, Museum of the Biblical Lands, the Supreme Court, Bank of Israel, and the Academy of the Hebrew Language.

All these institutions, together with the national library and many Israeli government ministry offices, reinforced the Zionist and scientific character of the areas under Israeli control in “West Jerusalem,” giving a strong boost to academic and research activity at the university.

Despite the political difficulties in Palestine, the early years after the new campus’s inauguration saw registrations of students and professors from around the globe. New scientific and engineering programs opened, reinforcing the university’s reputation as a leading research institution in Israel and in the Western academic world.

However, simultaneously, the Hebrew University implemented systematic policies to erase Palestinian and Eastern Arab identity through research and academic policy. It concentrated on agricultural and industrial studies, engineering, urban and geographic disciplines—fields used to build a Western academic reality for the Jewish settlers—while neglecting the Palestinian history of land and place.

Despite this academic and cultural orientation toward Western strategy, the university reactivated its original campus at Mount Scopus, which had been shut down during the military conflicts following the Nakba. Its civilian status secured international protection that allowed its academic activity in this disputed territory to continue.

Through that protection, the campus received regular supplies from the Western section of Jerusalem (86 policemen and 35 Israelis biweekly), together with international forces ensuring compliance with the protection principle and protection from threats by the Jordanian side.

This international protection smoothed the way for unifying the old Mount Scopus campus with the new Givat Ram campus—a matter settled after the 1967 war—making the university a central academic node in Israel.

Roles Beyond Academia

From the beginning, the founding of the Hebrew University was part of the Zionist project that aimed to strengthen Jewish culture in Palestine at the expense of the local cultures of Arab citizens. Colonialism and racism were basic elements in forming this educational institution. It adopted purely Jewish academic curricula, encouraged the strengthening of the Zionist narrative, and ignored Palestinian identity.

In the plan Geddes prepared for the university, the goal was to combine orientalism and Jewish heritage, in pursuit of the Zionist dream of building a Jewish nation in Palestine based on the Torah. That design carried a clear colonial flavor, exceeding the concept of an academic institution to become a political tool to consolidate settlement and occupation.

During the Nakba, the Hebrew University contributed to the occupation through the participation of the Haganah in establishing a “Science Corps” inside the university campus. This corps was not merely a research unit but a center for supporting military capacities and weapons production; professors and students participated in developing techniques that directly served military operations aimed at displacing Palestinians from their lands.

Following the Nakba, the second campus of the University was built on lands of the depopulated Palestinian village, Lifta, making the Hebrew University part of the settlement process in Jerusalem. Thus the institution became an instrument to uphold and institutionalize occupation by integrating education with settlement policies in the Arab city of Jerusalem.

Between the Nakba and the Naksa, and amid Arab efforts for higher education advancement, the Hebrew University early on presented itself as an institution open to Arab students—a claim later shown to be mere political promotion. Under growing oppression, it closed its doors to Arabs, imposing discriminatory laws and increasing restrictions.

As the university expanded, its role as supporter of the settlement project increased. In recent years, it issued tenders to build buildings on occupied Palestinian land—for example, for faculty housing of 700 rooms and 90 apartments in 2022, stretching from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood to the French Hill, on lands seized from the Palestinian villages of al-Issawiya and Shuafat.

Additionally, the university participates in the “Hafetselot” project, which aims to train elite soldiers in the Israeli army. Military students are required to attend academic programs at the university, to establish military barracks within the campus. They must appear on campus in uniform, carry their weapons, reinforcing security oversight and integrating soldiers into academic settings.

As a result of these roles, Palestinians have waged continuous struggle against Israeli academic institutions, primarily the Hebrew University. Key moments include the founding of the Arab University Students Movement in 1959, which expanded after the 1967 defeat (Naksa) to student committees at Haifa University, the Technion, and Israeli universities such as Bar-Ilan and Ben-Gurion.

Though its demands were simple—equality in education, housing, scholarships, employment they maintained a nationalist character that led to severe repression by university and government authorities.

In 2004, a group of Palestinian academics launched a campaign for academic and cultural boycott, calling on researchers worldwide to boycott Israeli academic institutions. They argued these were for decades part of the “regime of oppression” against Palestinians, that they played a primary role in planning, justifying, and implementing Israeli occupation and apartheid policies.

This campaign later crystallized into the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which gained support from more than 170 Palestinian civil society groups, including labor unions, refugee rights associations, women’s groups, grassroots popular committees, and other NGOs.

Today, the Hebrew University continues to support academic programs focused on training Israeli soldiers and enhancing their military capacities. Responsible for more than 41% of the startups founded on scientific research, it maintains its support for Israeli military industries. It contributes to development of engineering and industrial technologies serving companies like Rafael and Israel Industries.

University students also get the chance to test their experiments and research in the Palestinian field—on people, land and environment—making Israeli scientific work part of its capacity to field-test its products and prove their effectiveness, even as these cause destructive psychological, social, health, and environmental effects upon Palestinians.

In conclusion, despite the Hebrew University’s efforts to portray itself as a center of pluralism and political openness, the dynamics of the conflict between occupier and the original inhabitants continually return it to square one: a stronghold of settlement striving to stay in place and expand whenever possible at the expense of land, history, future, and people using military tools wrapped in academic and cultural trappings. The important thing is that it not collapse, so that the last citadels of Zionism do not fall with it.