At a very early stage, Zionism realized its need for a voice—whether in print or broadcast—to reach its emerging audience in Palestine, an audience that grew steadily with the unnatural influx of Jewish migrants from across the globe.

At that time, confrontation was not its immediate goal. Its priority was to entrench itself, adopting the English language and a conciliatory tone until it secured dominance over the media scene—only then revealing an unrelenting hostility and a torrent of crimes.

If you know how "Bank of Palestine" became "Bank of Israel," and how the Palestinian pound became the Israeli pound, then you've already traveled half the road to truth—and the full distance to understanding the Zionist media machine and its messages. If you don’t, this article explores the evolution of a newspaper that grew into a media conglomerate and eventually a global network, all while maintaining a consistent editorial line and a unified message across its various platforms.

This edition of the "Haaretz and Its Sisters" series focuses on The Jerusalem Post—perhaps the most subtle yet pivotal player in the Judaization of journalism in historical Palestine. It traces the newspaper’s origins, its trajectory, editorial policy, domestic and international positioning, and its portrayal—or lack thereof—of Arabs and Palestinians.

Agronsky’s Dream Realized

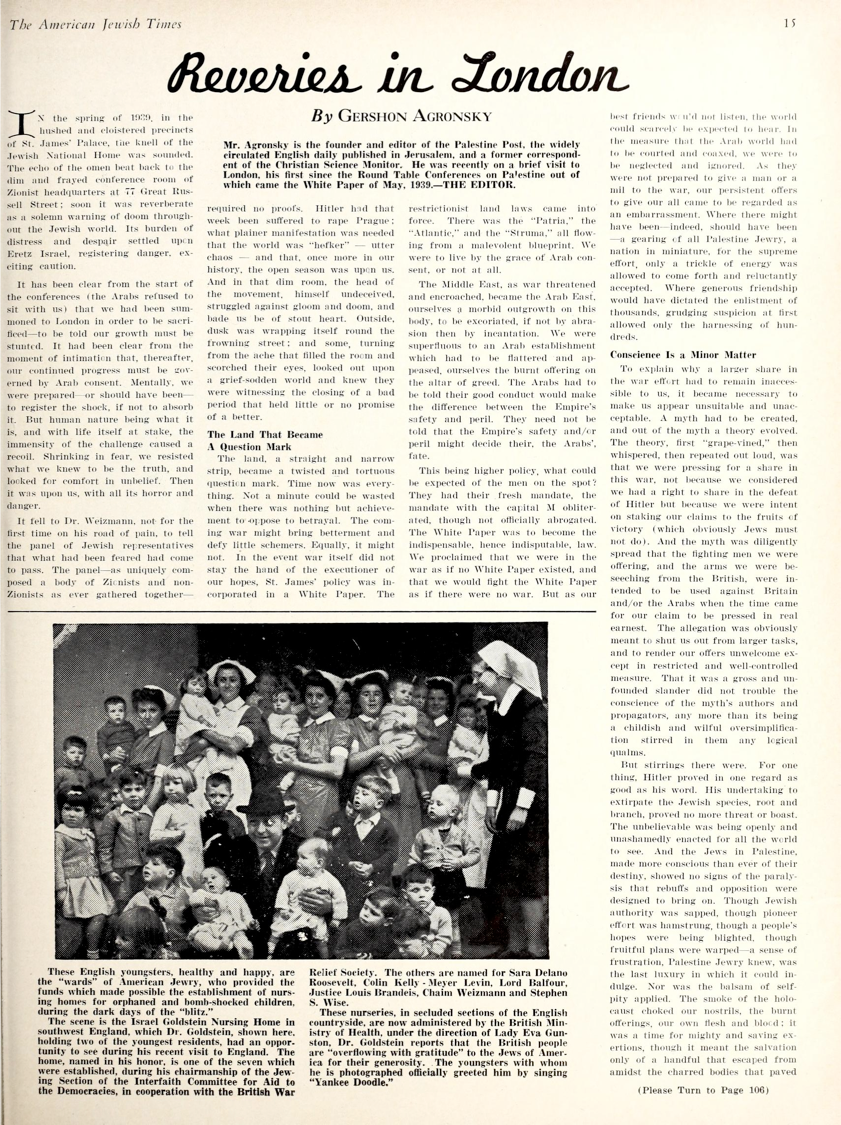

It’s difficult to pinpoint a single moment as the true beginning of The Jerusalem Post, or tie it to a specific event. The newspaper’s launch date does not reflect its ideological essence—a complex blend of Western Zionist imperialism that its founder, Gershon Harry Agronsky, diligently promoted, and which continues to this day.

Agronsky, a Russian Jew raised in a traditional Jewish family in Eastern Europe, was originally destined to become a rabbi. But fate took him across the Atlantic to the United States, where he met his friend Israel Goldstein in Philadelphia. Together, they founded the "Zionist Boys Club" when Agronsky was just 14.

By 1908, Agronsky had shaped his Zionist identity and began seeking a personal route to settle in Palestine. He wrote to Arthur Ruppin—appointed by the Zionist Organization to establish a Palestine office and coordinate Jewish immigration—asking which career path would most benefit the Zionist project. Ruppin suggested engineering.

As Agronsky moved through American universities—Temple, Gratz College, Dropsie College, and the University of Pennsylvania—he discovered a passion for journalism. He began writing for English- and Yiddish-language Jewish newspapers, eventually becoming editor of Das Jüdische Volk (The Jewish People), founded by the World Zionist Organization in New York in 1917.

A year later, he joined the Jewish Publication Society and worked to supply Jewish soldiers in World War I with religious books. But he didn’t stop there—he enlisted in the Jewish Legion, the first Jewish military formation since the fall of the Kingdom of Judah nearly 1,800 years earlier.

In the Legion’s 40th Battalion, Agronsky worked on recruitment alongside Joseph Trumpeldor, enlisting the likes of David Ben-Gurion, who joined the 39th Battalion, and Louis Fischer, among others. Agronsky was appointed spokesman for American Jewish soldiers in the Legion.

His time in the Legion offered him key advantages. Personally, he visited Ottoman Palestine for the first time, deepening his commitment to the Zionist cause. Institutionally, he leveraged his role to boost the visibility of American Jewish participation in the war and retained Legion records under the pretext of security.

He also authored a booklet titled Survey of the Jewish Battalions, which he submitted to the American Zionist Organization, enhancing his media and organizational status within the movement.

After the British Mandate over Palestine was declared in 1920, Agronsky returned to the US as part of the World Zionist Organization’s delegation, led by Chaim Weizmann and including figures such as Albert Einstein and Menachem Ussishkin. This delegation led to the creation of Keren Hayesod, a major Zionist fundraising body that expanded to more than 45 countries.

Agronsky went on to found the American Jewish Legion Organization, prioritizing settlement in Palestine. He launched the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), which grew into a key global news source for Jewish affairs, with over 400 Jewish and non-Jewish publications subscribing.

Using his political and media connections, he promoted Jewish immigration to Palestine by publishing correspondences with US President Warren Harding and Vice President Calvin Coolidge, and Britain’s ambassador to Washington—letters affirming support for a Jewish state in Palestine.

He showcased American popular support for Zionism, citing $4 million in donations to bolster the legitimacy of immigration and settlement.

While working as editor at JTA, Agronsky wrote extensively about Jewish settlements (Yishuv) and kibbutzim in Palestine, publishing in outlets like The Times, Manchester Guardian, Daily Express, and United Press International—leveraging international media to advance Zionism.

His belief in the world’s need for greater “awareness” about the Jewish role in Palestine led him to create a Zionist press office in 1924, disguised as a “Public Relations Office” in Jerusalem. He served as “Commissioner of Press Relations” for the Jewish Agency’s Political Department. This office eventually evolved into the Israeli Government Press Office, a major player in shaping Zionist media narratives.

He launched a multilingual weekly defending the Yishuv and promoting tourism and immigration to Palestine. Yet, he ran into resistance from the Associated Press, which refused to publish his work due to its policy of avoiding Jewish affairs.

By 1927, circumstances shifted in his favor. When an earthquake struck Jericho, his English fluency and media savvy catapulted him into the spotlight. He secured a cooperation deal with International News Service (INS), then America’s third-largest news agency.

As a correspondent for several papers, he launched the Palestine Bulletin, distributed to Jews in the Arab world. But mounting editorial restrictions and the 1929 Western Wall Uprising pushed him to start a paper that would fully express his political vision—including openly advocating for arming Jewish immigrants.

In 1932, he proposed the idea to American-Jewish businessman Ted Lurie, and after overcoming financial hurdles, The Palestine Post launched on December 1, 1932.

The Palestine Post: Voice of the Jewish Agency

At a time when English-language Jewish newspapers were nearly non-existent, The Palestine Post emerged to give the “Jewish National Home” project a voice in English—delivering an unambiguous Zionist message and entirely disregarding the native Arab population.

This blend of ambition and exclusivity helped the paper quickly gain traction, especially among Ashkenazi immigrants. The first issue ran just 1,200 copies, filled largely with British Mandate communiqués and military news from Egypt. The paper had more typesetters than writers—but within a year, its circulation quadrupled. It became more consistent and diversified in content.

In just two years, The Palestine Post became the leading newspaper in Haifa, Tel Aviv, and Jaffa—hubs for Jewish immigrants from Western Europe, Germany, and the US. It also attracted British Mandate officials, Jewish residents, and Western civilians, eventually reaching readers in Egypt, hiring correspondents in Arab countries, and opening a Beirut bureau. It added a cartoon section and sports pages focused on cricket, a favorite British pastime.

Politically, the paper was affiliated with Mapai, the forerunner of today’s Labor Party. It received financial and moral backing from the Jewish Agency, which used its pages to promote immigration, settlement, and the seizure of Palestinian land. It reinforced the Zionist narrative that Palestine was “a land without a people,” catering to a Western mindset that ignored Palestine’s deep-rooted Arab presence.

Over time, The Palestine Post, or “The Post” as it was nicknamed, became the unofficial mouthpiece of the Jewish Agency. It enjoyed British Mandate support, publishing official notices and speeches, which boosted its credibility among Western media. British High Commissioner Harold MacMichael called it a paper that “presents facts fairly, respects secrecy, and avoids both sensationalism and arrogance.”

By 1939, the paper openly criticized Britain after the White Paper restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine—deeming it a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration. It documented violent clashes between Jewish immigrants and Palestinians, consistently offering a pro-Zionist perspective.

By 1942, the paper severed ties with the British Mandate amid mounting tensions with Zionist paramilitaries like the Irgun and Lehi. It shifted focus to Jewish suffering in Europe during the Holocaust and intensified calls for Jewish immigration to Palestine—especially from the US. The paper highlighted Jewish participation in WWII, portraying Jews as a credible military force ready for statehood.

In 1947, following the UN Partition Plan, the paper devoted major coverage to promoting the plan as a stepping stone to a Jewish state. As violence escalated, the paper ran daily logs of the clashes. Agron described them as tools to “boost morale and rally spirits,” reinforcing the paper’s propaganda role in Zionist political and military efforts.

Amid curfews and street battles, Agron and his staff risked their lives just to reach the newsroom. The paper actively supported the Jewish paramilitary campaign. Consequently, The Palestine Post became a target: on February 1, 1948, Palestinian fighters bombed its headquarters—located near British censorship offices, Haganah command, and Jewish police stations—killing four settlers, including three staffers.

Abdul Qader al-Husseini claimed responsibility, with fingerprints of resistance leader Fawzi al-Qutb evident to both British intelligence and Zionist militias.

Despite the attack, the paper resumed publishing within a week, now more aggressively inciting violence against Arabs and urging recruitment for the coming showdown with the British Mandate—seen by Zionists as a critical juncture.

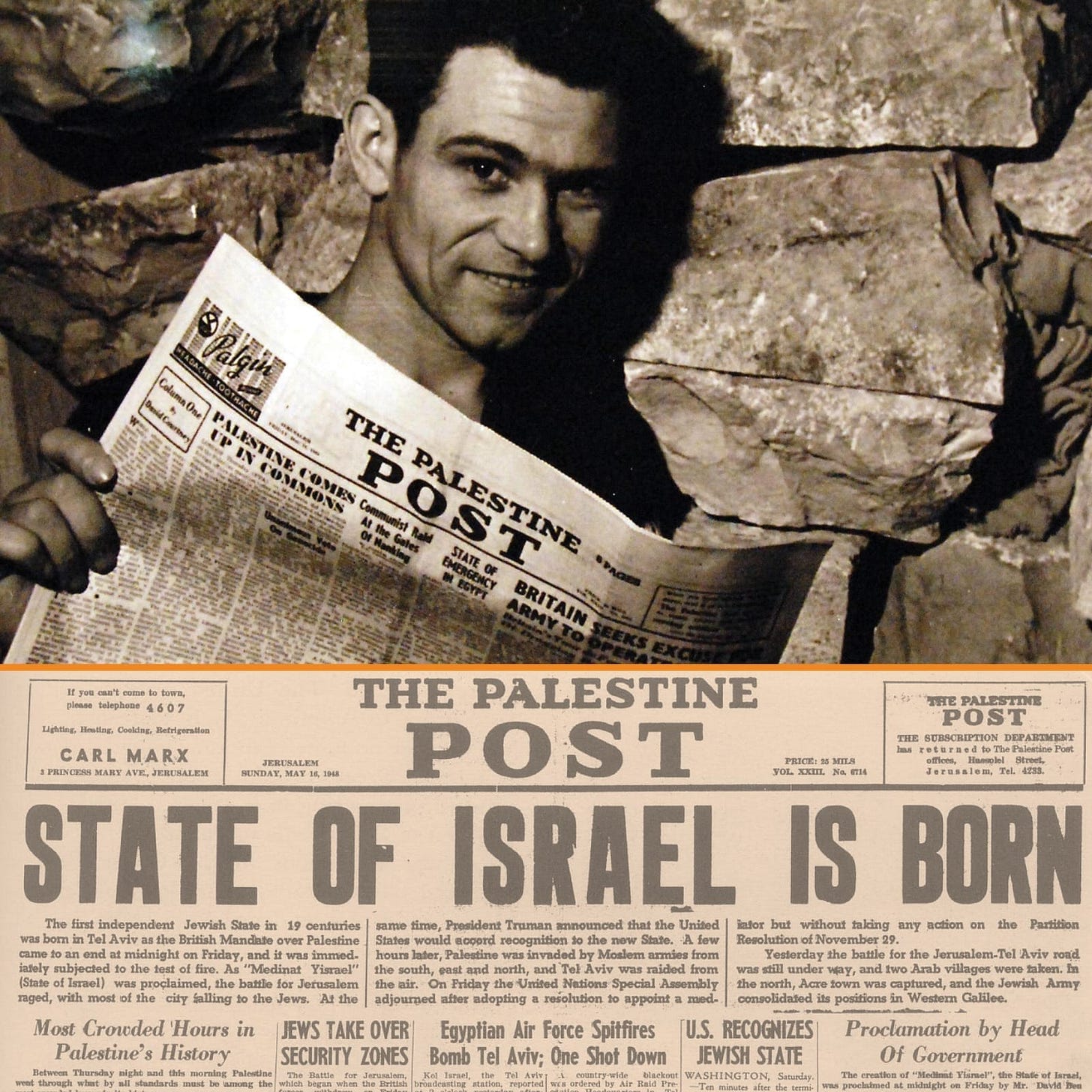

In mid-May 1948, the paper released a special edition titled “The Birth of the State of Israel,” filling its pages with David Ben-Gurion’s declaration, last-minute preparations, and early recognitions by the US and France. Even after the state's establishment and occupation of Palestinian lands, the paper continued to publish under the name The Palestine Post for two more years.

A well-known anecdote from the second anniversary of the state recounts editor Meir Ronen asking Agronsky: “Why keep the name Palestine when it hasn’t existed for two years?” Agron agreed. The next issue appeared as The Jerusalem Post—coinciding with Agronsky’s adoption of a more Jewish-sounding surname: Agron.

The Jerusalem Post in the Eyes of Global Media

Although founded before the creation of the Israeli state, The Jerusalem Post has consistently maintained its editorial line, policy, and target audience—unchanged to this day. Initially the voice of the Jewish Agency, it later evolved into a staunch defender of Israeli government policies, using its pages to advocate for Jewish immigration, military aggression against Palestinians, settlement expansion, and the expulsion of Arabs.

Its international press ties enhanced its reach. With links to The Times, Manchester Guardian, Daily Express, and United Press International, the paper became the most widely circulated in the Middle East during WWII and the favorite among Allied troops.

Agron treated the newspaper as his personal mission. He covered key events like the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt, the 1939 White Paper, the sinking of the Struma off the Turkish coast in 1942, and the deportation of Jewish immigrants to Mauritius by British authorities—earning recognition as a war correspondent.

By 1945, he was writing for The Daily Telegraph and Exchange Telegraph, while The Jerusalem Post became the go-to English-language news source on Israel for foreign media.

Understanding its role as a bridge between Israeli policy and the global community, the paper launched IVRIT, a Hebrew-learning magazine, followed in 1959 by a weekly international edition summarizing domestic news. In 1990, it launched The Jerusalem Report, distributed in France, Canada, the US, and Israel. Later, it embraced the digital era with online magazines.

Despite its unwavering support for Israeli state policies—including the repression of Palestinians inside Israel, the occupation of Palestinian territories after 1967, and the Judaization of holy sites—the paper continued forging international partnerships.

In 2008, it partnered with The Wall Street Journal to co-market and distribute the American paper exclusively in Israel. Earlier, it had launched a simplified Hebrew monthly.

Following the example of The Times, it began publishing an annual “Top 50 Most Influential Jews” list each Jewish New Year. In 2012, it launched international events, including a high-profile conference in New York that brings together key global Jewish figures and Israeli officials to discuss media and political influence. The initiative was spearheaded by the paper's CEO, Inbar Ashkenazi.

These partnerships extended beyond journalism. In 1989, the paper was sold to Hollinger International, a Canadian media empire and then the world’s third-largest, which also owned The Daily Telegraph, Chicago Sun-Times, National Post, and hundreds of local papers in North America.

From 1990 to the early 2000s, editorial leadership shifted repeatedly, including Jewish, American, international correspondents, ex-military personnel, and politicians—ranging from centrist to hard-right ideologies. Notable editors include Bret Stephens (now a New York Times columnist and NBC News contributor, and former Wall Street Journal editor), and Yaakov Katz (former military correspondent and defense editor).

Palestinians in the Margins of The Jerusalem Post

From its founding by Agron in 1932 through its rise as a leading Israeli publication, The Jerusalem Post has never strayed from its uncompromising Zionist line—whether in supporting settlements, justifying Israeli aggression, or manipulating media narratives in favor of the occupation.

From Agron, who led the paper for 23 years aligned with Mapai and David Ben-Gurion, to the editorial instability between 1990 and 2004 marked by seven successive editors, the editorial stance against Palestinians remained unchanged.

Whether under centrist editors like David Makovsky and David Horovitz, or far-right ones like Bar-Ilan and Bret Stephens, the paper has consistently rejected Palestinian recognition or political legitimacy.

Despite presenting itself at times as “independent”—free of British Mandate influence, labor governments, or Likud politics—the paper has never opened its platform to Palestinians. It has clung to an absolute Zionist ideology since inception.

On settlements, the paper consistently supported expansion and published voices in favor. As for the two-state solution—which implicates either ongoing annexation or territorial compromise—every editor has deemed it “unfeasible and undesirable.” Katz, formerly a military correspondent and later appointed to Naftali Bennett’s government before returning as editor-in-chief in 2016, openly opposes any form of Palestinian political recognition.

Bret Stephens took this rhetoric further, describing Arabs as “mentally ill with antisemitism” and promoting the racial superiority of Ashkenazi Jews.

When addressing displacement, the paper used euphemisms like “evacuation,” “resettlement,” and “relocation,” framing it as a security need while legally justifying Israeli land ownership and criminalizing Palestinian presence or expansion.

This approach extends to coverage of genocide, where Israeli war crimes are downplayed or reframed as “anti-Israel incitement.” Rather than calling out atrocities, it promotes the narrative of “legitimate defensive war” and brands military campaigns as anti-terrorism operations.

The paper has long questioned peace accords with Egypt and Jordan while celebrating normalization with Gulf states and North African countries. Investigations, however, revealed its role in coordinated media manipulation for friendly Arab regimes.

In 2020, Reuters exposed The Jerusalem Post and three other Israeli outlets publishing ghostwritten propaganda articles. The Daily Beast reported the paper was part of a 19-avatar network that published over 90 articles glorifying the UAE and attacking its regional rivals, including Qatar, Turkey, and Iran.

Unlike other outlets that later apologized or removed content, The Jerusalem Post ignored the scandal—reflecting its commitment to using media as political leverage for Israel and its allies.

These incidents underscore the paper’s influence in shaping Western opinion—and the weakness of Arab media, which often echoes its reporting, particularly outlets labeled as “moderate” in Israeli discourse.

This includes Al Arabiya, Sky News Arabia, Alhurra, and others that reprint or adapt its articles. Post-Abraham Accords, Bahraini and Emirati media even publish its content verbatim—especially regarding bilateral ties and security cooperation.

Researcher Karim Qurt explains that The Jerusalem Post differs from other Israeli newspapers mainly in its credibility among Western audiences, helped by its English-language format. This grants it significant global reach and influence.

He stresses the need for a critical, cautious Arab approach to Israeli media, noting that content is subject to military censorship. Contrary to the belief in full media independence, Israeli outlets operate under tight control, especially during war.

Qurt adds that Israeli media follow self-imposed boundaries—most importantly national security, which many Israelis treat as a parallel religion.

In conclusion, The Jerusalem Post is not isolated. It is part of a larger, highly coordinated Israeli media system that serves its audience and advances Zionist narratives at every level—local, regional, and global. This system, composed of both left- and right-wing outlets in Hebrew and English, operates as interconnected gears in a single machine.