Just ten days after the launch of “Al-Aqsa Flood,” the brutal campaign of killing and destruction in Gaza forced Western audiences to confront a historic dilemma: Is Israel a colonial occupier? The portrayal of October 7 as the starting point of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian people emerged as an untenable distortion.

While the Israeli occupation insists on playing the victim and using the events of October 7 as justification for its war on Palestinian existence in the West Bank, Gaza, and the occupied interior, Palestinians continue to assert that the conflict began with the Nakba in 1948, when the Israeli apartheid regime cemented its settler-colonial presence on their land.

What Zionist historians have dubbed the “War of Independence” was, in truth, a defining rupture in the history of the Palestinian people and their land—a violent climax of a process that began earlier and intensified through key turning points in 1948 and later 1967, followed by the so-called “external peaks” such as the Oslo Accords in 1993 and the Abraham Accords in 2020.

At every juncture, the Zionist project has been buttressed by a sophisticated ecosystem of quasi-governmental institutions that ensured its survival, expansion, and ability to outmaneuver adversaries by maintaining robust international ties—channels through which it has continuously received a lifeline of money, weapons, expertise, land, and education.

In our “Civilian Settlements” file, we explore the hidden roots of the colonial project in Palestine, tracing the foundational institutions of this system and examining their critical roles both before and after the Nakba in supporting and expanding the settlement enterprise. Many of these institutions later evolved into official government bodies that continue to carry out their colonial mission to this day.

Among these institutions was the Jewish Colonial Trust, which played a vital role in collecting funds and financing the establishment of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine. It became the financial backbone of the Zionist movement in the early 20th century, aligning itself with the settlers’ ambitions and adapting to their ever-expanding goals.

Financing as the Backbone of the Project

While the First Zionist Congress and the organization it spawned are commonly regarded as the cornerstones of the colonial settlement in Palestine, the Jewish Colonial Trust predates both. Its founding idea dates back to 1896, when Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism, concluded that the establishment of a Jewish homeland would require financial backing—specifically, the leasing of land, including from the Ottoman state in Greater Syria (the Levant), to lay the groundwork for a permanent Jewish presence.

At the First Zionist Congress, held under Herzl’s leadership in Basel, Switzerland, in August 1897, he called for uniting Jewish efforts to establish a national homeland. The options on the table included Argentina, Uganda, or Palestine.

After extensive discussions with Jewish communities in Europe and the United States, Herzl solidified his vision of Palestine as the Jewish homeland. Two institutional arms emerged from this decision: the World Zionist Organization (administrative) and the Jewish Agency (executive).

At the Second Zionist Congress—now a global event—several executive bodies were formed under the Jewish Agency, including the Jewish Colonial Trust. Its mission was to raise money to support Zionist immigration to Palestine, buy land, build settlements, and stimulate economic development. The trust was designed to overcome earlier failures (1882–1897) in establishing a viable Jewish presence in Palestine and to introduce financial and economic planning to ensure expansion.

It’s important to distinguish between the Jewish Colonial Trust and the Jewish National Fund (JNF). The Trust served as the financial and banking organ of the Zionist movement, aiming to reduce its dependence on European states until full independence could be achieved. The JNF, by contrast, functioned more as a charitable fund that collected donations from global Zionists specifically for land purchases and settlement building—without engaging in commercial or banking activities.

Zionist scholar Joseph Jacobs argued that the Trust’s establishment reflected the founders’ belief in the need for a dedicated financial institution to manage Zionist funds with the efficiency of a modern bank—modeled on British commercial systems. The idea was that Jewish immigration and settlement in Palestine should not rely on sporadic donations but on a financially independent and strategically managed operation.

Thus, in 1898, the Trust began operations. A preparatory committee comprising David Wolffsohn, Bodenheimer of Cologne, and Rudolf Schauer of Mainz issued a founding statement and opened subscriptions. Its stated goals included economic development, strengthening Jewish colonies in Palestine and Syria, and buying land for new settlements “under publicly and legally recognized frameworks.”

In commercial terms, the Trust aimed to promote trade, industry, and commerce within Jewish colonies, offer loans via bonds and mortgages, provide settlement advances, and establish savings banks or financial offices within the colonies. It also prioritized acquiring concessions in Asia Minor especially in Syria and Palestine—with a focus on railway concessions and port construction. Despite its ambition to raise £8 million, it managed only £395,000 in its first year.

By the second and third years, subscriptions increased with contributions from Russian and American Jews, raising over £2 million (more than 5 million gold lira). Herzl later offered this sum to Sultan Abdul Hamid in exchange for a decree allowing Jewish immigration and autonomous rule in Palestine. The offer was rejected.

Israel’s First Bank: The Anglo-Palestine Bank

As the financial arm of the Zionist movement, the Trust established its own bank within the British banking system. In late 1902, it opened a branch in London under the name Anglo-Palestine Bank, explicitly to finance “the establishment of the Land of Israel.”

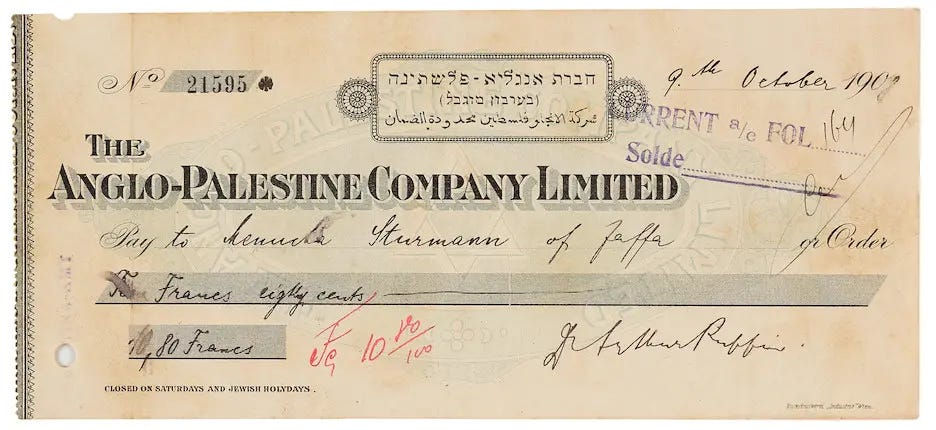

With a modest capital of £40,000, the bank quickly opened a branch in Jaffa, aided by the influence of Russian-Jewish banker Zalman David Levontin, whose ties to the British consul and leadership among Jewish settlers—particularly in the nearby Rishon LeZion colony—proved pivotal.

The bank gained a reputation for reliability and quickly expanded beyond commercial transactions. It bought land, acquired industrial and agricultural concessions, and began dominating import chains. It also formed a network of credit unions for emerging settlements and offered long-term loans to farmers.

It financed the first 60 homes in Tel Aviv’s earliest Jewish neighborhood through loans to the settlement association Ahuzat Bayit, circumventing Ottoman laws that prohibited land transfers to Jews, even those who were Ottoman subjects. Over the following years, it opened branches in Jerusalem, Beirut, Hebron, Safed, Haifa, Tiberias, and Gaza.

As the bank grew, accumulating land and funding kibbutzim and settlements, the Ottoman authorities designated it a hostile institution due to its British registration. Moves were made to shut it down and confiscate its assets.

During World War I, facing economic depression and the Ottoman seizure of its deposits, the bank’s activities became clandestine. Levontin traveled across Europe to raise new funds for the struggling settlement project, eventually relocating to Alexandria, where he opened a temporary branch to assist Jewish settlers expelled from Palestine and to collaborate with the British military.

In early 1918, he returned to Palestine, reopened the bank, and inspired Jewish investors to establish more banks under Ottoman law. These included the Palestine Cooperative Bank in Tel Aviv, known as Kupat Ha’am (“The People’s Fund”), which supported small to mid-sized agricultural, commercial, and industrial settlement projects.

From the Palestinian Lira to the Israeli Shekel

After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the onset of the British Mandate in 1920, the Anglo-Palestine Bank expanded openly. The Trust invested in new ventures, including the General Mortgage Bank, Bank Hapoalim, and the Palestine Electric Company.

However, the Trust later faced crises, including deep involvement in dubious Jewish financial operations in Eastern Europe, such as the Lodz Deposits Bank, the Jewish Central Bank, and the Kovno Union, leading to the freezing of over £550,000 in assets.

As a result, the Anglo-Palestine Bank grew in influence at the Trust’s expense. Under financial strain, the Trust collapsed and was absorbed into the bank as a shareholder, losing its commercial and economic privileges. In 1932, the bank moved its headquarters from Jaffa to Jerusalem.

During World War II, Levontin cemented the bank’s status by convincing British officials of its strategic value. The bank began funding Jewish military industries supplying the British army.

Although the Zionist movement had extensive financial and military infrastructure by 1948, the early years after the Nakba revealed how difficult it was for the occupiers to impose their authority—even on the currency.

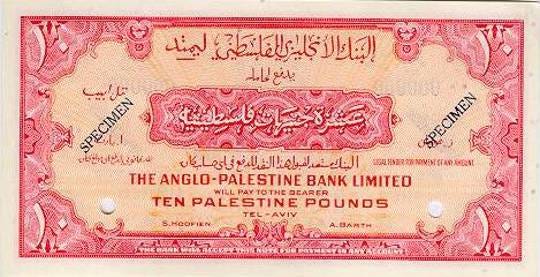

From 1948 to 1952, the Anglo-Palestine Bank continued operations until it was renamed Bank Leumi Le-Israel. By 1954, it became the sole major bank in Israel. Banking regulations were rewritten under Israeli law, and the bank launched over 20 international branches. In 1952, it issued the first Israeli currency, replacing the Palestinian lira.

In 1954, currency authority shifted to the newly created Bank of Israel. By 1969, the Israeli lira was replaced by the old shekel, and the agora coin (Hebrew for "piece of silver") was introduced. The lira remained in circulation until February 1980, when inflation forced a switch to the new Israeli shekel, still in use today.

Despite whitewashing its financial legacy and narrowing its commercial role, Bank Leumi remains implicated in the settlement project. In October 2017, Denmark’s Sampension pension fund divested from the bank due to its involvement in illegal settlements.

In February 2020, the UN published a database of 112 companies implicated in settlement expansion in the West Bank, Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights—classifying their actions as violations of international law and ongoing colonialism. Bank Leumi was included for providing services that enable settlement growth.

In July 2021, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund also divested from the bank. Financially, the bank was hit with a $400 million fine in 2014 for helping American clients evade taxes.

In 2023, Bank Leumi was implicated in an investigation by Israel’s Foreign Ministry, State Comptroller, and Asset Management Unit for withholding Holocaust victims’ bank accounts and failing to return them to their heirs after WWII.

In 1955, the Jewish Colonial Trust was restructured as an Israeli company named Otsar Ha-Hityashvut Ha-Yehudit, and its stake in Bank Leumi was liquidated. In 1969, its capital was increased from 7 to 10 million through bonus shares, with 12% dividends announced for 1968. In the late 1980s, the Trust was sold to private investors.

The Jewish Colonial Trust, which remained active for nearly 70 years before and after the declaration of Israel’s statehood, played a foundational role in building Israel’s banking infrastructure. It facilitated economic ties with Western and Eastern Europe and the United States and helped liberate the Israeli currency from market constraints and crises.

Its rise and decline expose Israel for what it has always been: a modern colonial state. And just as the Zionist project was built with meticulous effort, subversion, and displacement, dismantling it will require an equal measure of determination and persistence.