On September 1, 2024, the Jewish National Fund (JNF) in Israel signed an agreement with its counterpart in the United States to launch a joint project aimed at rehabilitating and developing southern towns and resettling settlers in the area. Each side is expected to contribute $25 million to land development, job creation, and urban revitalization, all in service of attracting more Jewish immigrants to the region.

This project sheds light on the powerful role the JNF plays in sustaining Israeli settlement and maintaining Israeli presence on Palestinian land—an undertaking it has pursued for more than 123 years, even before the establishment of the State of Israel.

In this installment of our "Civilian Settlement" file, we delve into the hidden origins of the colonial project in Palestine, exploring the foundational objectives behind institutions like the JNF, their pivotal roles before and after the Nakba, and how many of them evolved into state entities that continue their colonial function to this day.

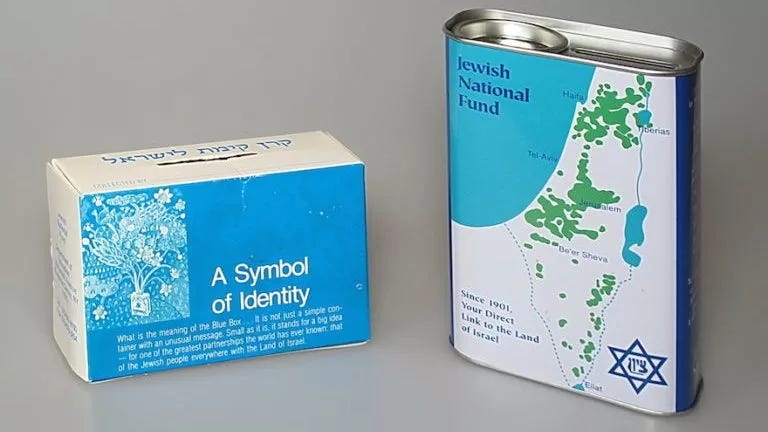

At the heart of this architecture stood the Jewish National Fund—a movement that began with a blue donation tin that traveled the world, funding the purchase of land, the relocation of settlers, their employment and education, and even influencing politicians and reshaping landscapes to suit their vision.

The Blue Tin: Donating for a Homeland

The idea of the JNF was first conceived by Russian-Jewish mathematician Zvi Hermann Schapira, an ardent advocate of settling in Palestine. In 1884, he proposed the establishment of a national fund to support land acquisition in Palestine—a concept he later presented at the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897.

Although initially overlooked, Schapira reintroduced the idea at the Second Congress, presenting a physical model: a large blue metal box, 24 centimeters tall and 9 centimeters wide, adorned with a map of the eastern Mediterranean. It was an invitation to donate toward the creation of a Jewish homeland.

Four years after his death, the blue tin was officially adopted at the Fifth Zionist Congress in 1901, along with Schapira's detailed proposals, which formed the founding principles of the Jewish National Fund, known in Hebrew as "Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael"—“the fruits we eat today are the roots of their future.”

Headquartered initially in Vienna under Russian-Jewish president Johann Kremenetsky, the fund soon expanded globally. Six years after its founding, it was registered as a British-chartered charity aiming to “eradicate Jewish poverty,” and later moved its headquarters to The Hague, Poland during World War I.

Between the two World Wars, the blue box became a prominent fundraising symbol for the Zionist cause. It embodied Jewish unity, linked deeply to religious traditions and the sacred act of giving. The boxes became ubiquitous in Jewish communities throughout Europe and the United States.

Fueled by rising Jewish nationalism, thousands volunteered to spread the message, turning the blue tin into a symbol of Zionism itself. By the eve of World War II, over a million boxes circulated in Europe, channeling all contributions to the JNF under the pretense of “fighting poverty,” though the real aim was colonization.

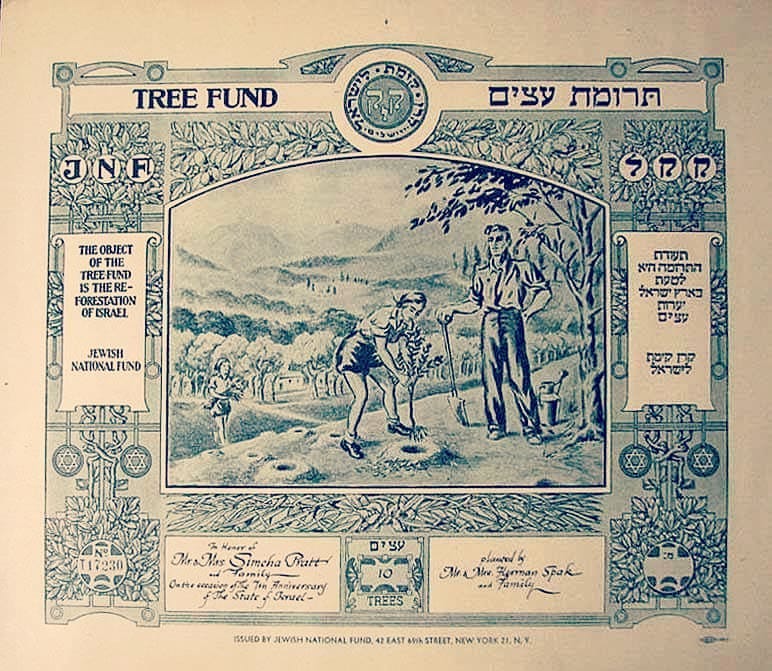

Blue stamps soon joined the campaign, emblazoned with JNF emblems and depictions of the “Land of Milk and Honey.” They featured Jewish farmers, builders, early settlements, rabbis, and slogans like “Your direct route to the Land of Israel” and “Revive and reclaim the Land of Israel”—an ideological bridge between donations and settlement.

Relocating to Jerusalem

In 1919, the JNF saw two major turning points: the appointment of Abraham Ussishkin—Russian-Jewish Zionist and founder of the "Bilu" movement—as chairman, and the relocation of its headquarters to Jerusalem, taking advantage of the newly established British Mandate over Palestine.

With this move, the fund took a more aggressive role, especially under Ussishkin’s rivalry with British Jerusalem Governor Sir Ronald Storrs. Ussishkin preempted the construction of a British university by launching the Hebrew University project, and persuaded High Commissioner Herbert Samuel to recognize Hebrew as an official language alongside English and Arabic.

Within a decade, the JNF had purchased land near Jerusalem, the Jezreel Valley, Haifa Bay, and Beisan. Revenues grew from 70,000 to 600,000 Palestinian liras, and swamplands were drained, wells dug, and deserts reclaimed in the Negev. Wealthy Jewish donors toured these projects, and annual conferences were held on seized lands to showcase progress.

By this point, the JNF had become Zionism’s executive arm. It was hailed as a pioneering force in "sustainable development" for the Jewish state, and any land it owned was declared “the property of the Jewish people,” not subject to sale or transfer.

The fund forged strong ties with global Jewry, drawing on donations, rental income, and investments in elite Jewish professionals and influencers in the West. It helped establish the Technion Israel’s first institute of higher education—and a year later, the Hebrew University, fulfilling Schapira’s dream.

It had already helped found the Bezalel Academy and agricultural schools, and cultivated links between Palestinian research centers and Jewish scientists abroad.

Esteemed figures like Albert Einstein, Chaim Nachman Bialik, Ahad Ha’am, Nahum Sokolow, and Judah Magnes were enlisted as trustees, solidifying Zionist institutions’ academic and cultural clout.

By 1947, the JNF owned over 933,000 dunams of land—6.6% of Palestine. Its reach expanded to military-agricultural kibbutzim, particularly along border areas, and it preemptively acquired strategic land in anticipation of war or political shifts, including swaths of the Negev and the Jezreel Valley, often in coordination with Israel’s water and electricity companies.

The Nakba—and After

On the eve of the Nakba, the JNF’s staff were preparing for a historic conference—later remembered as the event marking Israel’s founding—held on land owned by the fund. The creation of the state, however, triggered a transformation: the fund now had two urgent tasks—“cleansing the state” and “expanding it.”

Its first mission: erasing Palestinian presence. The JNF took control of depopulated towns and absorbed them into its holdings, which came to represent 13% of occupied Palestine. These lands were exclusively allocated to Jews, excluding Palestinians entirely.

In tandem with military operations, the JNF worked to obscure the devastation of the Nakba: demolishing villages, planting forests atop ruins, converting sites into Jewish heritage parks, and repatriating the remains of “early Zionist pioneers” to reframe history.

In A Charitable Trust Complicit in Ethnic Cleansing, Uri Davis describes the JNF as a vehicle of erasure—creating lush green parks funded by foreign branches, such as Canada Park (built on the ruins of ‘Imwas, Beit Nuba, and Yalo), or South Africa Forest in Lubyah.

Researcher Khaled Mustafa calls these “colonial forests,” engineered to mask ethnic cleansing and replace Palestinian heritage with a European landscape, thereby reducing Jewish settlers’ sense of alienation.

JNF Settlement Director Akiva Ettinger (1924–1932) insisted that the land should reflect the European environment settlers came from. Thus, pine forests were prioritized over native flora like oaks, hawthorns, carobs, and olives—to recreate a European "home."

Restructuring the Fund Post-Nakba

In the years following the Nakba, the JNF underwent restructuring in three phases. The first came in 1953, with the passage of the "Keren Kayemeth Law," which granted the fund public authority status, enormous financial privileges, and planning and ownership rights. Lands it owned were reclassified as “state or public property.”

In 1954, as part of a broader state centralization effort, the Israeli Knesset restricted the JNF’s operations to land inside present and future Israeli borders. The fund’s mandate expanded beyond land acquisition and afforestation to include job creation and health services for new immigrants.

By 1961, in a move to enhance the state’s democratic image, the Israeli government signed an agreement with the JNF defining their legal and financial relationship. It confirmed that the fund’s activities would be financed through global Jewish donations and rental income—without direct state funding.

Despite this reorganization, the JNF never ceased its ecological transformation of Palestine’s geography. From draining Lake Hula to channeling water to the Negev, to foresting the Upper Galilee to create buffer zones with Lebanon, and separating East from West Jerusalem through forested corridors, its projects reshaped the land.

Among them was the Yatir Forest north of the Negev. Under the guise of “development projects,” the JNF continued the internal displacement of Palestinians by converting Arab lands into parks and forests named after Western donors—thus creating physical and environmental barriers separating settlements from Arab towns and granting settlers exclusive access to leisure spaces.

The fund’s influence extended beyond forestry. In 1950, it backed the "Black Goat Law," which equated the presence of black goats with Arabs on the land. Citing a Talmudic passage—“Do not raise lean animals in the Land of Israel”—the law aimed to eliminate black goats, which allegedly harmed pine saplings planted by the JNF.

To justify the law, the JNF imported a Swiss breed of white goat—the Saanen—promoted as docile and productive. It launched public campaigns with slogans like “lovable and harmless,” and created social clubs such as the “Beloved Goat Association.”

Meanwhile, over 42,000 black goats were rounded up and slaughtered. They were labeled “devious, unruly, destructive, and enemies of the environment.” By 1960, the Saanen goat population reached 32,000, while the indigenous black goat was nearly eradicated.

The Green Organization that Swallowed 1967

Driven by its obsession with afforestation, the JNF began marketing itself as the world’s first “green organization.” It claimed to combat climate change, turn deserts into forests, and swamps into fertile plains replacing the “black goat” with the “blonde goat,” and painting a European paradise on stolen land.

Between 1901 and 2001, the JNF claimed to have planted 250 million pine trees, built over 200 dams and reservoirs, controlled 250,000 acres, and established more than 1,000 parks. But beneath the greenery lay a legacy of uprooted people, trees, animals, and communities.

Following the 1967 war, the JNF quietly expanded its settlement role in the occupied Palestinian territories. Through its West Bank subsidiary, Himanuta, it acquired over 65,000 dunams between 1967 and 2019.

The fund spearheaded settlement construction along the Jordan Valley from the Dead Sea to the Red Sea. In the early 1990s, over a million Russian and Ethiopian immigrants were settled in the Hula Valley and employed in West Bank settlement projects.

The JNF also funneled roughly 88 million shekels into West Bank settlement activity, and undertook legal procedures to evict Palestinians from their homes.

In Jerusalem, its affiliate Elad (the “City of David” Foundation) led the seizure of Palestinian homes in Silwan and Wadi Hilweh, claiming to restore properties allegedly owned by Jews before 1948. Elad became the JNF’s legal front, fighting courtroom battles that resulted in the confiscation of Palestinian homes under Israel’s “Absentee Property Law.”

In the past decade, the JNF took charge of the “Israel 2040 Resettlement Project,” aiming to expel Palestinians from the Negev and settle one million Jews in their place, and another half million in the Galilee.

The project promised a “renaissance” for Israel’s north and south, in coordination with the government, military, academia, and the private sector. Plans include establishing over 750 companies and attracting 150,000 Jews to the labor force.

It dovetails with regional transport initiatives, seeking to turn the Negev into a hub between Haifa and neighboring Arab ports. The region is also slated to become Israel’s weapons manufacturing capital.

But in 2021, tensions flared with the US Reform Zionist movement, which opposed the JNF’s renewed focus on settlement. Ignoring objections, the JNF allocated $1.2 billion to purchase West Bank land—effectively nullifying the 1954 law limiting its jurisdiction to sovereign Israeli territory.

Corruption Beneath the Surface

Despite its vast assets and global reach, the JNF has not been immune to allegations of corruption, financial mismanagement, and illegal privatization of “state” land. Its international branches, particularly in the US, manage assets worth over $2.5 billion and collect over $100 million annually in donations.

Critics have called for the fund’s dismantlement and transfer of its assets to the state. In 2014, to avoid public scrutiny, the JNF launched a campaign to exempt itself from state audits, allocating millions of shekels in political donations to Likud, Labor, Shas, Yisrael Beiteinu, and Meretz. Likud alone received 1.3 million shekels.

On the international stage, the JNF came under fire after October 7, when it was revealed that its branches in the US, UK, Australia, Germany, and Canada had funneled money to politicians and influencers, and financed trips to Israel.

In the UK, over a third of Conservative MPs—126 members—received donations and hospitality worth more than £430,000, attending over 180 “solidarity missions” to Israel sponsored by pro-JNF groups.

The latest scandal came in July 2025, when Canada’s revenue agency announced plans to revoke the JNF Canada’s charitable status for using donations to build infrastructure for the Israeli military—violating Canadian tax law.

The notice cited the JNF’s ties to Himanuta and Elad and their role in land grabs across the West Bank, with the goal of stripping Palestinians of their property.

In the End…

Despite the exposure following October 7, it is unlikely that any scandal—no matter how egregious—will alter the JNF’s trajectory.

What is striking, however, is how every Zionist initiative began with something small—often a single coin or a symbolic object—then expanded through focused messaging, strategic vision, and relentless execution to become a massive financial and institutional power, a “state within a state.”

And yet, this only deepens the admiration for Palestinian resistance and steadfastness, from before the Nakba to today. This resistance has stood firm against a global Zionist machine with far-reaching capabilities and influence. It has faltered at times, but rebuilt itself time and again, always rising to fight from the origins of oppression to its modern manifestations—undaunted, undeterred, and unbroken.