The Layers and Masks of the Nakba: What Was Left Untold About the Fragmentation of Palestinian Society and the "Favored Minorities"

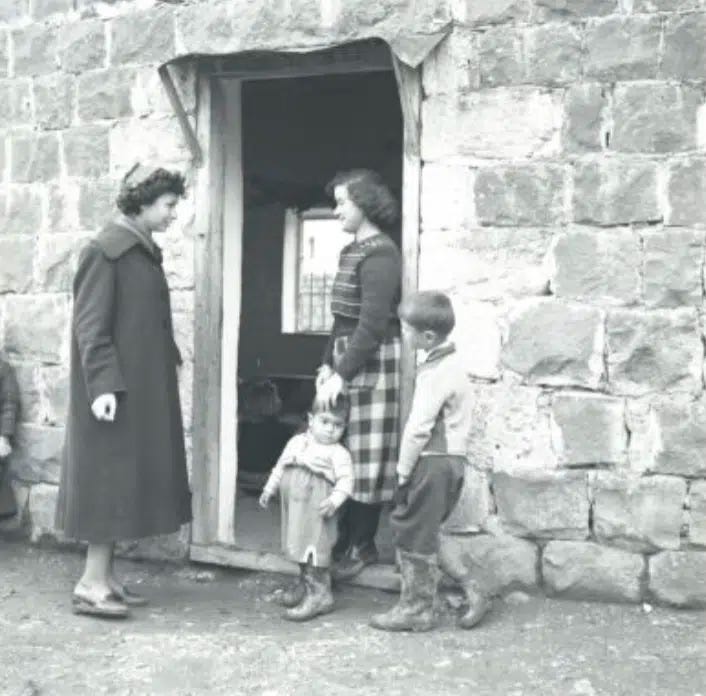

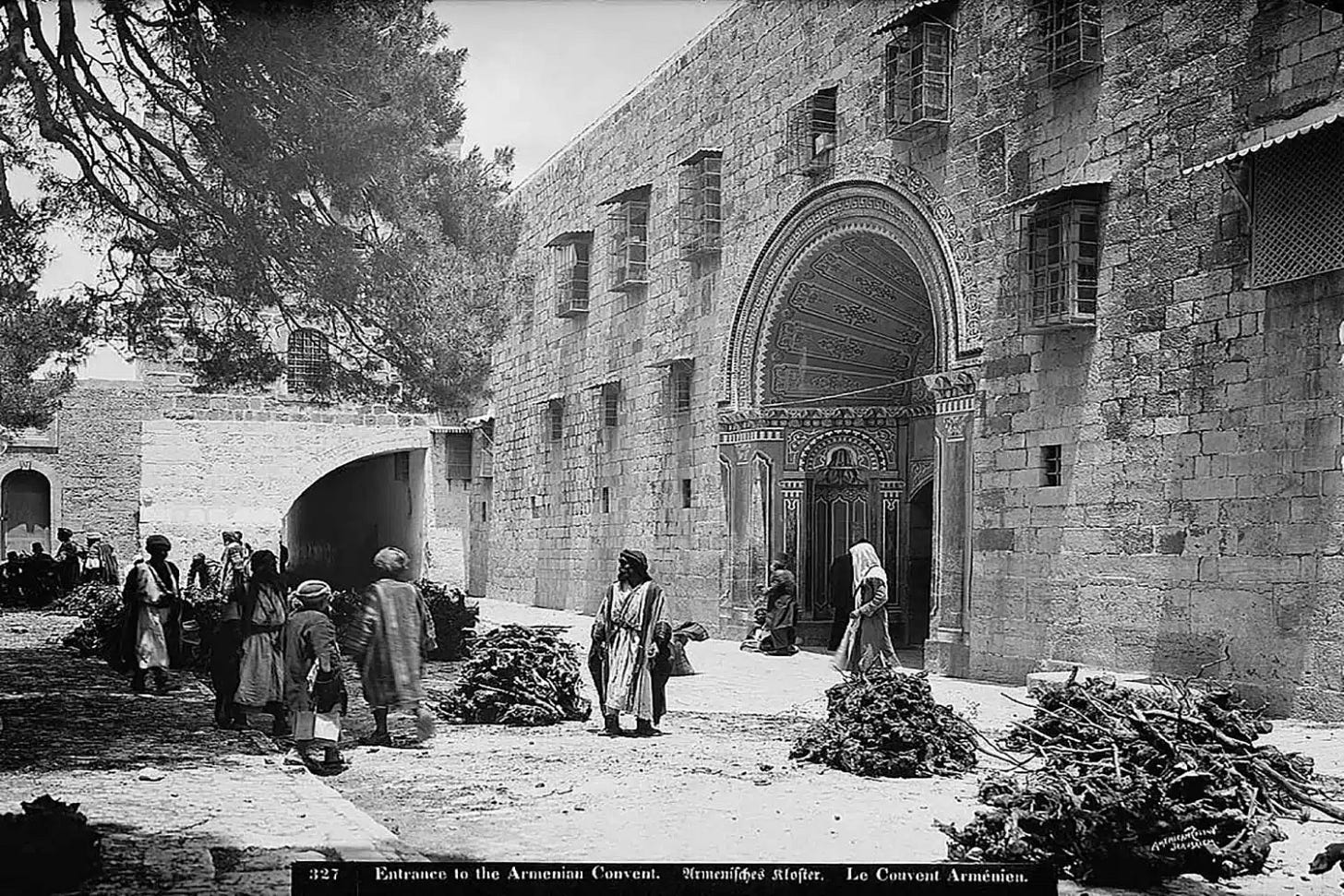

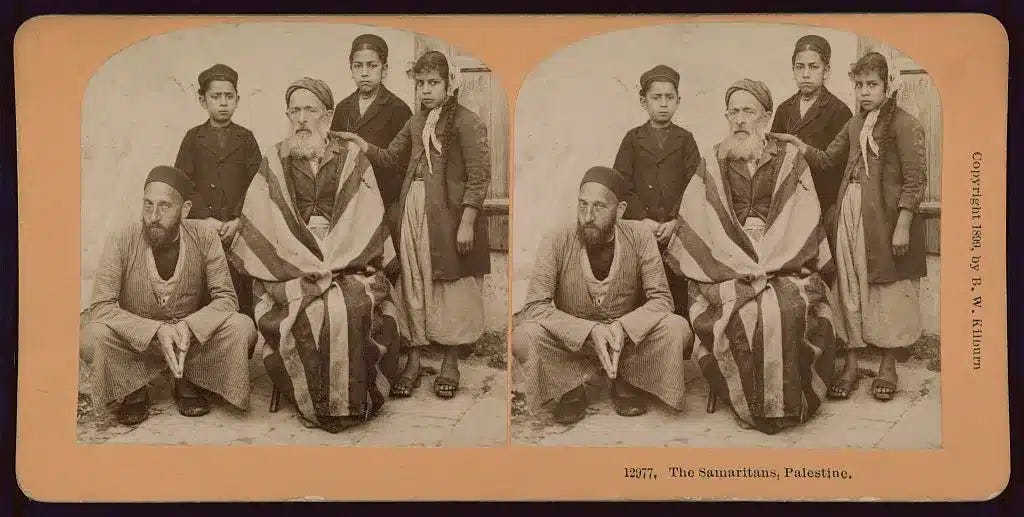

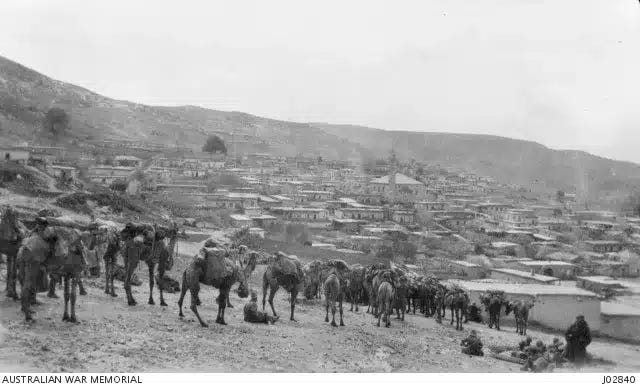

If you have ever come across old photographs of Palestine before the Nakba, you would uncover a different dimension of the Nakba’s story—one invisible even in color. Christian women in the markets of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, Baháʼís in Haifa and Mount Carmel, Samaritans standing atop Mount Gerizim, and Bedouins roaming with their livestock across the plains of Hebron and Bethlehem—these scenes captured colorful ethnic and religious diversity, with only faint religious symbols marking their cultural dress.

This textured mosaic of communities, rendered in black and white or faded greyscale images, was deliberately erased from the historical narrative of Palestine and the decisive moment of the Nakba. The result: a landscape flattened into a binary conflict between Jews and Muslims, as though the Zionist movement carried the mantle of the Crusaders in their war against the Muslims of the Holy Land.

Perhaps that is why the Western capitals erupted in celebration when General Allenby entered Jerusalem in 1917, or when Moshe Dayan marched into the Haram al-Sharif in 1967.

This erasure served the Zionist movement on multiple levels: it reframed the issue as a religious conflict between two faiths; it rallied Western Christian support for the Zionist cause; and it underpinned the long-standing strategy of "divide and conquer"—a tactic Zionism adopted both before and after the Nakba.

This strategy helped win over various sects and ethnicities to its project, while also creating the illusion that its crimes only targeted Arab Muslims, sparing others and thus absolving itself in Western eyes.

On the anniversary of the Nakba, this article revisits the selective policies Israel implemented against Palestine’s diverse population, while highlighting the broader context of fragmentation across the Arab world.

Wherever ethnic or sectarian rifts exist, Israel finds fertile ground for expansion—feeding off fractures and multiplying within them, always at the expense of the native fabric of this land.

No Unified Identity for Palestinians

According to the first population census conducted by the British Mandate authorities in 1922, Palestine’s population totaled 757,182 residents, comprising a Muslim majority of 590,390, 73,024 Christians, 38,694 Jews, 7,028 Druze, 408 Sikhs, 265 Baháʼís, 156 Shia Muslims, and 163 Samaritan Jews.

Nine years later, on November 18, 1931, the Mandate government conducted a second census. It recorded a population increase of 36.8%, bringing the total to 1,033,314. This surge was most pronounced among Jews, due to organized immigration, whose numbers had risen by 108.4% to 174,610—surpassing the Christian population, which stood at 91,398.

Meanwhile, the Muslim population reached 759,717, the Druze numbered 9,148, the Baháʼís 350, and the Samaritans 182. As for the nomadic Bedouins in the south, they refused for the second time to cooperate with census officials, prompting the statistics office to estimate their number at 759,717.

The final census before the Nakba was carried out in 1945, jointly conducted by the Mandate’s Statistics and Land Office and the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine (UNSCOP). Its results laid the groundwork for UN Resolution 181, which called for the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state.

According to that census, based on general demographic proportions and supplemented with data from the Jewish Agency and immigration records, Palestine’s total population was 1,764,520, including 1,061,270 Muslims, 553,600 Jews, and 135,550 Christians. The rest—Druze, Baháʼís, Samaritans, and others—were lumped together under the category “Others,” totaling 14,100.

Despite major questions surrounding the census—particularly its reliance on projections based on 14-year-old data for all groups except Jews, and its heavy dependence on Jewish Agency figures that advanced the goal of establishing a Jewish state—the data still proves, beyond doubt, that the Jewish presence in Palestine was unnatural and its expansion aimed not only at displacing Muslims but also targeting non-Muslim Palestinians.

Palestinian identities are deeply rooted, not only in numbers but also in the political, religious, cultural, and economic contributions of all segments of society.

Christians in Palestine, for instance, were never marginal or peripheral; they played central roles in politics and national movements, producing influential figures such as Yusuf al-‘Isa (founder of Al-Karmel newspaper), George Antonius (author of The Arab Awakening), and Issa al-Bandak (mayor of Bethlehem and editor of Sawt al-Sha‘b).

This list also includes pioneering writers and publishers like Khalil Baydas, Emil al-Ghouri, Iskandar al-Khuri, Najib Nassar, Emile Habibi, and Hanna Abu Hanna—intellectuals who shaped an inclusive national discourse that transcended sectarian divides.

Economically, Christians were also trailblazers—establishing workshops, trades, banking institutions, and a robust press (Falastin, Al-Difa‘, Al-Karmel). In education, they founded schools, printing presses, and cultural clubs such as the Arab Orthodox Club, and connected Palestine to the Arab world in Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt.

The Druze contributed significantly to agriculture and livestock herding, maintaining a cohesive local economy and balanced relations with Muslims and Christians, despite their religious conservatism and relative isolation.

The Armenians, meanwhile, introduced photography to Palestine, established its first printing press in Jerusalem, and became renowned goldsmiths—forming an artisanal class that played a key role in Jerusalem and Jaffa, including the upkeep of churches and religious landmarks.

This applies also to other minority groups like the Circassians, Baháʼís, and Samaritans, who enriched Palestinian life through their contributions across sectors, solidifying Palestine’s place as a vital part of Greater Syria—“Southern Syria”—and as a bridge linking Istanbul, Damascus, Beirut, and Alexandria. This significance carried into the diaspora experiences of Palestinians after the Nakba.

The economic and cultural vitality of some communities, along with tendencies toward neutrality or seclusion, may explain why Zionist policies were often lenient toward them—or excluded them from direct expulsion plans.

In this sense, the Nakba was more than a sweeping act of ethnic cleansing; it was a complex scheme of population engineering that preserved certain groups in targeted areas for long-term strategic use, redistributed others functionally, and uprooted the majority to fulfill a larger settler-colonial goal.

The Nakba as a Selective Policy: Who Is Displaced and Who Remains

Ethnic composition, population distribution, and political, economic, and cultural engagement all play critical roles in deconstructing the Nakba through the lens of minority communities. This reveals how Christian, Druze, and then Bedouin populations experienced the Nakba differently from the Muslim majority, their presence reshaped rather than obliterated.

This disparity is evident in areas where these communities concentrated—Galilee, the coast, and the south—and in how they were redistributed after the Nakba under Israel’s strategic logic: Who lives near “secure” borders? Who is deeply integrated into the broader Palestinian or Arab landscape? Who can be politically or economically co-opted? Who can be separated from Palestinian national identity through isolation, fragmentation, or reinvention?

Christians of the Holy Land

From this angle, it becomes clear that Israel, after dealing with the Muslim majority, focused on demographic density as a means of controlling the demographic balance. This explains why Christians, like Muslims, were expelled from coastal cities, and why Christian villages along the northern border with Lebanon and Bedouin concentrations in Wadi Ara and Beersheba were similarly targeted.

The Druze, meanwhile, were “retained” for purposes of political co-optation and containment.

Prior to the Nakba, Christians lived across Palestine—in Jerusalem, Haifa, Jaffa, Nazareth, Bethlehem, Ramla, Lydda, and Safad—and often constituted significant portions of these populations. They played pivotal roles as thought leaders, entrepreneurs, and influential cultural and political figures.

After the Nakba, however, Christian presence was largely confined to Nazareth and surrounding villages in Galilee. More than 60,000 Christians were displaced from cities like Haifa, Jaffa, Ramla, Lydda, and Safad.

Their share of the population fell from roughly 10% to less than 2% today. Their involvement in the national movement, especially during the 1936–1939 revolt, likely accelerated Zionist efforts to expel them from central and coastal regions.

It’s crucial to note that their survival in Nazareth was not due to some special immunity, but rather Israel’s deliberate policy to preserve a marginal “image of religious diversity” to placate the international community—particularly given Nazareth’s global Christian symbolism and its churches, notably the Church of the Annunciation.

Just as demographics drove the expulsion of Christians from most areas, international pressure helped preserve their presence elsewhere. For example, the few Galilee villages that remained were not in direct geographic contact with Lebanese or Syrian villages across the border.

Villages on the “first line” like Maalul, Rameh, Iqrit, and Kafr Bir’im were cleared and replaced with Israeli settlements.

This distinction also played out in how expulsion occurred. For Muslims, Zionist militias employed mass killings, forced deportations, bombings, house burnings, and demolitions—blunt tools of terror and displacement.

For Christians, the methods varied: direct expulsion as in Lydda and Ramla; “encouraged departure” in places like Haifa; or “temporary evacuation” based on false promises of return, as in Iqrit and Kafr Bir’im. In some cases, churches, Western institutions, and Christian dignitaries intervened to halt displacement, as happened in Nazareth.

This differentiated treatment produced a new post-Nakba demographic reality. Some Christian families remained in neighborhoods in cities like Jaffa and Haifa, while most Muslim residents were expelled.

Some Christians returned to their villages; in mixed areas, both Muslims and Christians were expelled under the guise of “non-discrimination.” While some historic Christian villages in Galilee survived, Muslims were erased from most.

One striking disparity post-Nakba was that Palestinian Christians in Nazareth and Bethlehem retained urban, economic, and social infrastructure—and support from Western churches.

Their continued presence was later exploited to promote Israel’s image as a pluralistic state, in stark contrast to Muslim Palestinians, who lost their economic centers and social cohesion with the fall of major cities that linked them to administrative, financial, and academic networks.

Israel’s gain from selectively displacing Christians and Muslims went beyond propaganda. It was a calculated strategy of demographic curation. Christian Palestinians were, in general, urban, middle-class or above, and had longstanding economic ties to European and American markets.

Their education levels—both before and after the Nakba—were higher than among Muslims, Jews, and other minorities. Additionally, they had the lowest birth and natural growth rates in the country.

The Bedouins: Palestine’s Forgotten

This selective policy also applies, in part, to the Bedouins—whom Ghazi Falah once called “the forgotten Palestinians.” Indeed, they were marginalized before and after the Nakba. Urban Palestinian society did not fully integrate the Bedouins, which left them in a state of isolation that made them more vulnerable to Israeli targeting after 1948.

Yet, that isolation was not always a disadvantage. Bedouins actively resisted Jewish immigration and British colonial rule, and participated in the Palestinian Revolt by attacking British police posts and Zionist settlements, particularly around Baysan and Mount Carmel. They also sabotaged railway lines and blocked roads between colonies.

They joined early in the al-Qassam Revolt and in protests against British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel. Notable tribes like Arab al-Suqur, Arab al-Ghazzawiyya, and Arab al-Tarabin played major roles.

From a wide geographic spread that once extended from Beersheba to Gaza’s outskirts, from Marj Ibn Amer to Baysan and the depths of the Negev, Bedouins are now confined to unrecognized villages in the Negev.

These are subject to routine demolitions and forced evictions—like al-‘Araqib, which has been razed over 200 times, denied water, infrastructure, schools, and transportation.

In coastal, Carmel, and Marj regions, most Bedouins were displaced into limited enclaves like Zarzir, Tuba-Zangariyya, and Arab al-Shibli near the Jordan Valley. This displacement continued well beyond 1948, escalating between 1951 and 1953 under policies of “Negev development,” “soft transfer,” and population relocation.

Ironically, Bedouin survival in some regions had less to do with Israeli leniency and more with their own knowledge of the land. Their familiarity with the terrain allowed them to repeatedly return after expulsions, exploiting gaps in Israeli geographical knowledge.

Yet, despite their resistance, continued Israeli efforts forced a drastic decline: from around 95,000 Bedouins before the end of the Mandate to just 13,000 afterward. The rest were expelled to Gaza, Jordan, Sinai, Khan al-Ahmar, and Masafer Yatta.

The Bedouins of southern Palestine refer to their uprooting as “Kasrat Bir al-Saba‘”—the shattering of Beersheba, a phrase that embodies their catastrophe. Sixteen tribal leaders, out of 95 displaced tribes, formally petitioned the occupation authorities to remain on their ancestral Negev lands.

A month and a half later, the committee—comprising Yosef Weitz (known as the “father of afforestation”), General Yigael Yadin, and Yigal Allon—rejected the request, stating only “friendly tribes” would be allowed to remain. This prompted pledges of loyalty from some tribes, while others—like the al-‘Azazmeh—resisted, resulting in the expulsion of 700 of their members.

Today, only seven Bedouin villages in the Negev are officially recognized, compared to 180 Jewish settlements. The rest remain “unrecognized,” constantly threatened by demolition and eviction.

Despite the sweeping nature of the Nakba, some Bedouin leaders chose to negotiate separately with Israel. Under military rule, which deprived Bedouins of freedom and space, and given the deep attachment to land among Bedouins, Israel exploited this vulnerability.

Upon completing military service, Bedouin soldiers were allowed to apply for loans to purchase land and build homes—an option unavailable to other recruits. This lured some into homeownership at the cost of surrendering communal lands and collective identity.

Today, Bedouins constitute 5–10% of Israel’s military, mainly in the 585th Battalion, known as the “Bedouin Reconnaissance Battalion.” Founded in 1970, it handles tracking, border patrol, and infiltration interception along Gaza, Egypt, Sinai, and Jordan, and supports field operations. About 1,581 Bedouin soldiers serve in this unit alone.

Still, this figure remains small compared to the 300,000-strong Bedouin population. Recruitment is technically voluntary, but often incentivized through economic perks like loans and land ownership.

Nevertheless, deep-rooted national consciousness endures among many Bedouins, with numerous examples of resistance—such as detainee Shatila Abu ‘Ayadah, who carried out a stabbing operation and remains imprisoned, and activists Suleiman al-Hurbaid, Ya‘qub Abu al-Qi‘an, and Haitham al-Hawashleh.

One version of the battalion’s origin, cited in Israeli archives, recounts that during Operation Yiftach on the eve of “Independence Day” (the Nakba), Yigal Allon and the Palmach were unable to gather intelligence from Safad, which was under Arab control.

He turned to Sheikh Yusuf Hussein Muhammad al-Hayb of Tuba-Zangariyya, who sent two villagers to Safad. One was killed after refusing to swear on the Qur’an that he had no ties to Jews; the other survived. This led Allon and the Sheikh to form a Bedouin unit in the Palmach called “Balhayb,” named after the tribe.

Yet this recruitment was never an equal partnership—it was bait. Israel exploited Bedouin tracking skills unavailable to others and then discarded them. Even those who served were later denied equal rights.

Today, this reality persists. Homes of Bedouin soldiers from Tuba-Zangariyya—who served along the Lebanese border—were demolished while they wore IDF uniforms. Discrimination extends not only to infrastructure but also within the military, where non-Jewish units face systemic condescension and marginalization.

The Druze and Circassians: Isolation Toward Separation

In a rare act of principled resistance, the late scholar Qais Firro produced critical academic work on the Druze community's relationship with the Israeli occupation and the history of their conscription. He stressed that the mainstream Israeli narrative surrounding Druze conscription is incomplete and must be approached cautiously—especially when based on Zionist archival sources.

According to these archives, in May 1948, the Israeli intelligence officer Giora Zaid established the so-called “Minorities Unit” and issued orders forbidding Arabs from harvesting or burning wheat fields—except for those from the Druze community. Druze villagers were given a grim ultimatum: retain their lands in exchange for mandatory military service.

Firro argued that this move was not primarily military in intent but aimed at severing the organic connection between Druze and Arabs, especially their ties to Syria and Lebanon. It was also part of Israel’s image-making efforts—like with Christians—leaving Druze as a symbolic minority within the “Jewish state.”

He further noted that the Minorities Unit was not under the Ministry of Defense but rather the Ministry of Foreign Affairs—emphasizing the political and propaganda nature of the project.

Supporting Firro’s analysis are records showing that 23% of Druze Arabs participated in the 1948 war on the side of the Arab Liberation Army—exceeding their proportion in the Palestinian Arab population.

Druze Palestinians also took part in attacks on Jewish settlements during the 1920s as members of the “Green Hand Gang” led by Arab-Druze rebel Ahmad Tafesh. The group operated in northern Palestine for three years.

Druze involvement in Palestinian and Arab affairs remained strong until the early 1940s when Zionist leader Yitzhak Ben-Zvi recognized the strategic value of co-opting them. He supported efforts to challenge the dominance of Grand Mufti al-Husseini, promoted the sale of Druze tobacco via Jewish merchants, and encouraged friendly visits to Druze villages.

Despite these efforts, Israel’s “Minorities Unit”—which included limited Druze, Bedouin, and Circassian participation—failed in its first operation: an assault on the Druze village of Nahaf.

Local Druze, aligned with the national movement, inflicted heavy losses—41 Israeli casualties, including 11 Druze. Yet, this assault laid the groundwork for the later formalization of Israel–Druze relations through the so-called “Blood Pact” signed on October 29, 1948.

Under this pact, Druze were allowed to enlist in the Israeli military in exchange for unique privileges not extended to other minorities. Still, initial attempts to impose conscription faced resistance. Only 127 of 472 draft orders were fulfilled, and entire villages refused to comply.

At that time, strong Druze leadership—figures like Sheikh Farhoud Qassem Farhoud—galvanized opposition to conscription. But with the loss of Arab backing after the Nakba, the Druze became increasingly vulnerable to Israeli policy.

Even so, until 1965, Sheikhs Farhoud Farhoud and Amin Tarif supported draft resistance and enforced social boycotts on conscripts, including bans on marriage.

This changed in the early 1970s when Israel confiscated 83% of Druze agricultural land, their main livelihood. This economic blow drove many Druze into the military and security sector, beginning a shift toward forced conscription.

During this period, Israel passed laws separating Druze and Circassians from Arabs and Muslims—designating them as distinct ethnicities, imposing separate curricula, replacing Islamic holidays with Prophet Shu‘ayb Day, and creating separate administrative and legal systems.

This coincided with the decline of historic Druze leadership and the rise of a more pliant, less educated elite—facilitating mandatory conscription.

Today, about 85% of Druze youth are drafted into the Israeli army. Service begins at age 18, a result of systemic pressures including land confiscation and the collapse of traditional agriculture, driving young Druze to seek social and economic benefits through military service.

This situation parallels that of the Circassians, though with unique historical distinctions. Unlike Druze, Christians, or Bedouins—whose roots in Palestine go back centuries—the Circassians arrived more recently, between 1876 and 1878, after being expelled from the Caucasus by Tsarist Russia. The Ottoman Empire resettled them across Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine.

Roughly 950 Circassians settled in Palestine before the Nakba, belonging to the Shapsugh and Abzakh tribes, concentrated in Kafr Kama and al-Rihaniyya. They preserved their language and customs and were relatively new converts to Islam.

Their recent arrival, coupled with Ottoman decline and increased Jewish immigration, limited their integration into Palestinian national identity. Like other minorities, they adapted to shifting political powers and maintained cordial relations with various sides.

Some participated in the Palestinian Revolt—figures like Idris Hasan La‘sha and Ishaq al-Sharkasi engaged in clashes with British forces and Zionist guards.

Others, however, protected Jewish settlements and opposed Palestinian fighters. A school principal from Kafr Kama testified that Circassians aided nearby Yavne’el during the 1936 Revolt.

Palestinian fighters tried to recruit them during the 1948 war, but they declined, preferring neutrality—unlike their counterparts in Jordan and Syria who fought in the Arab Liberation Army and suffered casualties in Palestine.

During the Nakba, while Zionist forces ethnically cleansed much of Galilee, Circassian villages like Kafr Kama and al-Rihaniyya were left untouched. Explanations range from Israel’s divide-and-rule strategy to their low population numbers, longstanding ties with nearby Jewish settlements since the 1930s, and tensions with local Arabs stemming from past Ottoman allegiances.

Yet, this did not last. Within two months of the Nakba, Circassian volunteers from Kafr Kama participated in military operations in Nazareth, Shefa-‘Amr, and western Galilee alongside Haganah forces. They became part of the 12th Battalion of the Golani Brigade. With the formation of the “Minorities Unit,” Circassians, like Druze and Bedouins, were swept into Israel’s mandatory conscription system.

Historian Ilan Pappé noted that promoting Circassian participation in the Minorities Unit aimed to provoke Arab resentment. In fact, only five Circassians served—one from al-Rihaniyya, three from Kafr Kama, and one Syrian Circassian residing in Palestine.

In 1953, when the mukhtar of al-Rihaniyya, Hassan Bek, died, villagers nominated Rashid Ghash. Israeli authorities rejected him and appointed pro-Israel figure Jamal Khurshid instead. This triggered internal division and escalated after the assassination of a notorious informant. Israel responded with a village siege, arrests, and exile of seven families—more followed in 1957 amid land confiscations.

Kafr Kama’s land shrank from 8,500 to 6,500 dunums; al-Rihaniyya’s from 6,000 to just 1,600. To deepen the divide between Circassians and Arabs, Israel designated them as a separate ethnic group, imposed distinct school curricula, and enforced conscription—adding a new official holiday: “Circassian Exile Day.”

Today, there are about 4,000 Circassians in Israel, with around 75% serving in the Israeli military. They are considered among the most assimilated minorities, likely due to their small numbers and lack of institutions to preserve their cultural identity.

But that assimilation has not spared them from discrimination or racism—only repurposed them for Israel’s showcase of diversity in a state built on ethnic cleansing.

As such, both Druze and Circassians were placed in the same category—subject to the same racist laws that excluded everyone but Jews. The 2018 Nation-State Law (Jewish Nationhood Law) made this official.

Despite advances in education and living standards among some minorities, conscription remained compulsory, and nationalist movements among them were left isolated—ignored by the Arab world and manipulated by Israel.

What precedes raises a series of fundamental questions about what is hidden and what is revealed in the Nakba—its true nature and deeper reality.

Was it merely a case of ethnic cleansing, or a multi-layered project of minority engineering disguised as “positive discrimination,” often implemented under false pretenses?

What legal, administrative, political, and military tools did Israel use—before and after the Nakba—to intentionally fracture what remained of Palestinian society under the banner of “favored minorities”?

In Conclusion...

In this context, the question of narrative becomes urgent. The Nakba’s story cannot be singular. It must reflect the multiplicity of sects, identities, and affiliations.

There is a pressing need to return to the diverse Nakba narratives found in memoirs, oral histories, literature, and lived experience—and to reincorporate them into the broader Palestinian story.

The exclusion of minorities and sects from the collective memory is no accident; it is a deliberate erasure that serves one party alone.

But what is the purpose of all this?

The goal is to reframe the Nakba not as a one-time event but as an ongoing structure—1948 and the present Nakba—as the contexts evolve but the policies remain. The essence is unchanged. Another goal is to restore silenced voices—ethnic and sectarian—and return them to their rightful place in the collective national narrative.

Not for tokenistic inclusion, but to affirm a shared destiny and unify efforts in the face of collective annihilation—rather than scattering into isolated struggles for survival under overlapping threats of erasure.