If someone ever asks you where literature meets audacity, answer them directly: in the “National Library of Israel.” That answer alone is enough to make them understand how heritage, culture, and knowledge confront occupation, dispossession, and looting and how this incongruous mixture is given the name “National Library.”

If this answer is not sufficient, the following lines will reveal how the gang that raped the land and called it “Israel” did more than seize territory. It plundered other things, relabeled them to remove the stigma of theft, justifying its actions with a noble mission under the slogan “preserving heritage and knowledge.”

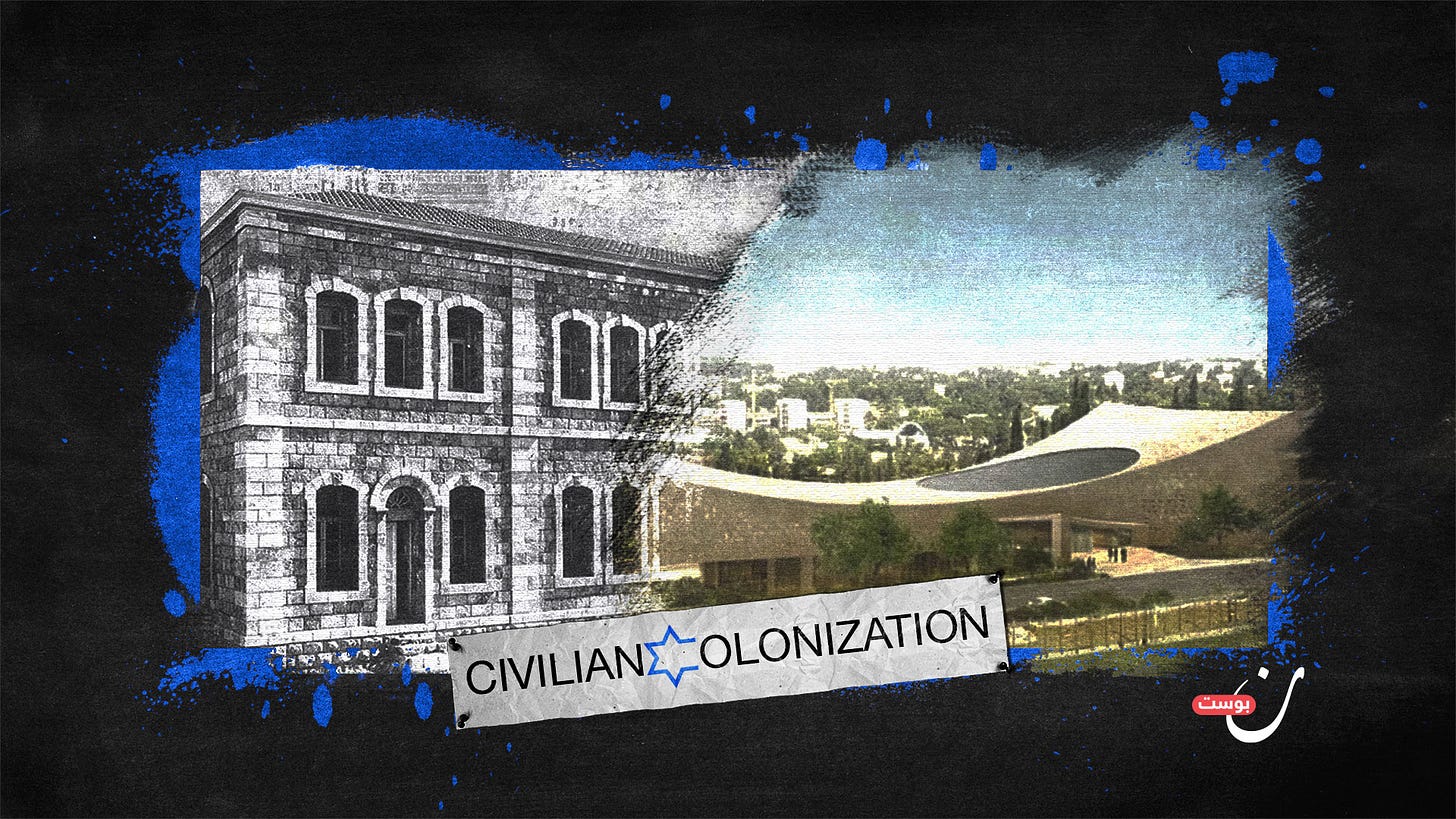

We return here to the dossier of “civil settlement,” to shed light on another aspect of the Zionist support network that contributed to founding the State of Occupation, and strengthening its political, economic, and cultural presence.

This time we pass through the shelves of the National Library of Israel, considered the “pride of Jewish culture,” to show how it became one of the main pillars of cultural Zionism and a tool for its academic and cultural normalization with the world reflecting Israeli audacity in appropriating the properties of Palestinians displaced from their lands, while claiming exclusive and eternal ownership.

An American Project to Zionize History and Heritage

At the end of 1843, one of the oldest Jewish organizations was established in New York under the name “B’nai B’rith.” Its main objective was to care for the Jewish immigrant community from Germany, and to create a fraternal system similar to other organizations based on lodges and conditional membership.

Over the years, the organization used its activities and members to influence U.S. policy to improve the situation for Jews in Europe, especially Germany. It also focused on collecting Jewish literary heritage from all over the world. In 1851 it established the first Jewish library in the United States called “Order Hall,” followed a year later by another library named “Moses ben Maimon Library.”

In 1868, B’nai B’rith achieved its first penetration into Ottoman Palestine through cooperation with the American Red Cross, collecting US$4,522 to assist cholera victims. Over time, its activities expanded in the Arab region: it established a lodge in Cairo in 1887, and another in Jerusalem in 1888 by Eliezer Ben Yehuda, known as “the father of modern Hebrew.”

Thus, B’nai B’rith became the first Jewish organization to hold public meetings in Hebrew, ahead of the First Zionist Congress led by Theodor Herzl in Basel by nine years. By the time that Congress was convened, the organization had already prepared its own agenda establishing a women’s branch called “Jewish Women’s Organization.”

It also established over 500 student Jewish organizations at universities, an organization in high schools named “Alef Sadik Alef,” two organizations for Jewish boys and girls, camps for Jewish children and youth, and an office for career services and counseling.

Despite its many branches, B’nai B’rith did not neglect the need to found a strong Jewish culture. It began launching Jewish libraries in Jerusalem by its lodge members, though the initiative did not completely succeed due to lack of funding.

In 1884, the organization renewed its attempts to establish a Jewish library. The new library included 1,200 volumes. Around the same time it founded The Menorah Monthly in 1886, the first Jewish magazine in the United States. In the July 1889 issue the magazine promoted a library and invited readers to donate to support its continuation.

Although that attempt failed, the organization did not stop trying. In 1892 B’nai B’rith established a new library called “Midrash Abarbanel,” named after the medieval Jewish philosopher and exegete Abarbanel, who lived during the Middle Ages and had a significant role in the courts of the kings of Castile, Portugal, and Naples. The first Jewish synagogue in Spain was also named Abarbanel; it opened on February 3, 1917.

Within three years of its establishment, the Midrash Abarbanel library, which was open and free to Jews, became an important cultural hub for Jewish settlers in Palestine.

As its collection of books and manuscripts increased, it was moved to a new location on B’nai B’rith Street, becoming the only place in Jerusalem offering books in subjects such as mathematics, the sciences, and secular philosophy.

Its expansion was supported by prominent Jewish scholars such as Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Isaac Newton. The library also became a social center for Jewish settlers.

This prompted Zionist leader Theodor Herzl to send a message to the Jewish Russian physician and intellectual Joseph Chazanovich, known for collecting books and manuscripts, urging him to support the library and gather Hebrew books and materials related to Jews and their Torah.

In his letter Herzl wrote: “In our holy city we should preserve all books in Hebrew, and all books in every language concerned with Jews and their Torah.”

Chazanovich responded swiftly. He transferred more than 10,000 books from his personal library in Bialystok, Poland to Jerusalem, contributing the nucleus of the library called Beit Hamachtarot (“House of Treasuries” in the European Jewish tradition — a term used for hiding precious possessions, underground resting places). In honor of his donation, the library was renamed “Midrash Abarbanel Jeinzai Yosef.”

In the same context, Herzl donated 300 rubles to the library, calling on Jews worldwide to donate books, manuscripts, and money. By 1903, the library held over 22,000 volumes in various sciences and languages, managed under the supervision of Samuel Hugo Bergman, who later became the first dean of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, a close friend of the writer Franz Kafka. He oversaw collecting manuscripts and ensuring their deposit in the library.

Amid this cultural-scientific surge, B’nai B’rith held its first conference in Jerusalem in 1905, supported by Jewish scholars and writers who sought greater settlement and expansion.

With the outbreak of World War I the library was closed by the Ottoman authorities; at that time its holdings had exceeded 30,000 volumes, and it was under the management of Avraham Cohen Reiss. After the war, the efforts of the library merged with the World Zionist Organization under the British Mandate, which supported transferring part of its collections to the Hebrew University when it opened on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem in 1925.

Simultaneously, the library adopted several names: “The National Library”, “The Jewish University Library”, or “Library of the Jewish People,” bearing a prominent Zionist slogan known as “making a nation for the people of the book.” The library contributed significantly to strengthening scientific, cultural, and academic relations between Jewish settlers and Western societies via B’nai B’rith and the World Zionist Organization.

From “Land Without a People” to “Books Without Owners”

After the partition of Palestine and the stages following that decisive era, the National Library of Israel entered a new phase in its history one that is especially clear to researchers and writers.

Although many of the Zionist foundations from which the library sprang are absent in much public awareness, it served as the cornerstone for cultural colonization of Palestinians causing a cultural Nakba that parallels in its severity the physical, human, and material losses inflicted upon land and people.

During that period, the Zionist militias carried out a systematic campaign against Palestinians, targeting Arab neighborhoods considered elite and educated such as Qatamon, Bak’a, Abu Tor, Talbiya, Musrara occupying them and displacing their residents. They replaced them with settlers, in an attempt to erase the cultural and human identity of those neighborhoods, as part of a deliberate cultural settlement.

Alongside that came military Zionist policies aiming to seize Arabic books and preserve Jewish ones. Some contents of the Jewish National Library were smuggled to multiple buildings in Jerusalem to preserve them from ongoing fighting. In contrast, Palestinian homes and libraries were looted and stolen by Zionist groups, which targeted books and manuscripts of educated Palestinian families.

In Jaffa, in the Nakba year 1948, the military governor Meir Laniado issued a military order banning removal of any Arabic book from the city, assigning the task of collecting books to the Minister of Minorities, Israel ben Ze’ev, specialist in Arabic literature and history.

In Qatamon books were collected from houses in a coordinated operation between the Israeli Army and Hebrew University showing coordination between military and cultural institutions in confiscating Palestinian books and manuscripts in a step meant to reinforce cultural settlement and marginalize Palestinian Arab culture.

According to a manuscript from the archives of the National Library written by a librarian in early 1949, the systematic theft involved over 50 prominent Palestinian figures whose personal libraries were seized including Mohammad Is‘af al‑Nashashibi, whose library held tens of thousands of books; Khalil al‑Sakakini, a Christian Arab educator and writer; also the library of Ya‘qub Faraj, leader of the Orthodox Greek community; Henry Cattan, member of the Palestinian judiciary between 1940‑1948.

In addition, the private libraries of writers and translators such as Khalil Beidas, translator from Russian; Dr. Tawfiq Kanaan, interested in folklore and descriptive ethnography; also Fuad Abu Rahma, former member of the Palestinian Council; Yusuf Heikal, mayor of Jaffa in 1947‑48, were targeted.

Despite the gravity of the crime committed by the National Library of Israel in seizing books and manuscripts belonging to Palestinians, it did not try to hide its actions. On the contrary, it sought to beautify them and depict them as part of original Zionist idea: “a land without a people for a people without a land.”

Thus, the stolen book becomes as though it were a “book abandoned without a reader, for a reader without a book.” The library even established what is called the “Abandoned Property Section,” which holds the stolen books although some Israeli sources estimate the number at 80,000 books, the archive of the library itself limits the number to more than 8,000 books only.

This cultural theft justification aligns with the view of Zionist historian Eliahu Ashtor, who described the seizure of the books as “collecting and preserving them from damage,” considering that removing them from Palestinian owners amounted to “liberation” of those books transferred to hands of others who “know how to benefit from them for science and humanity.”

On the homepage of the National Library of Israel, there is a blunt statement that the books left by Palestinians “just as they left their land,” were seized by the Israeli army and protected, while library employees collected them carefully.

These books include multiple languages Arabic, English, French, German, Italian which indicates that the looting was not limited to private homes but also targeted educational institutions and various churches.

In the archives of the National Library there are on display private works of the Palestinian intellectual Khalil al‑Sakakini, with his Arabic signature in black letters, alongside the library of Mohammad Is‘af Nashashibi, whose tens of thousands of books the library refuses to return to his heirs, despite repeated family requests.

The transformation that befell the National Library of Israel did not remain at simply expanding its holdings with stolen books. It coincided with further settlement: the library’s headquarters was moved to Givat Ram on the Hebrew University, built on the ruins of the Sheikh Badr neighbourhood the Palestinian village of Lifta, seized by Zionist militias, transformed into a site for Israeli government institutions, named Givat Ram.

With Hebrew University entering the process of cultural looting, a joint “Treasures of Exile Committee” was established between the university and the National Library, aiming to assemble cultural property in Jerusalem embodying Herzl’s vision of gathering the dispersed books in “our holy city.”

The work of the Treasures of Exile Committee included gathering books from Europe, instituting laws encouraging enhancement of the National Library’s cultural collection, expanding acquisitions and cultural appropriation in various ways. It also worked to reinforce the sovereignty of the Hebrew book, discarding manuscripts that did not serve Jewish literature.

By 1952, the committee had collected more than 439 manuscripts from Germany, which were distributed between Jerusalem, the U.S., and Canada. Additionally, more than half a million books were deposited in the National Library in Jerusalem during the three decades following World War II, helping to strengthen the library’s position as a cultural-academic center for the Jewish historical narrative.

That expansion was accompanied by the Israeli Knesset’s 1953 passage of the Legal Deposit Law, which required that two copies of every publication in Israel be deposited in the National and University Jewish Library, so as to preserve these publications for future generations.

The law applies to any book published within the borders of “Israel,” regardless of topic or language, which greatly expanded acquisitions of rare Islamic, Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern manuscripts. The library acquired manuscripts in hadith, poetry, Sufism, including works by Ibn Arabi, especially his Shams al-Ma‘arif.

In contrast, the library destroyed about 27,000 books belonging to Palestinians, under the claim they were worthless or contained content considered threatening to the State. Also, the cultural looting expanded: it targeted private manuscripts of Yemeni Jews, like Yemeni Torah manuscripts and personal religious contemplations of their sects, during the late 1940s and mid‑1950s.

More than that, the Yemeni book theft, estimated at thousands of books and over 300 Torah manuscripts, parallels that of the Palestinian books: both stem from a colonial premise that seeks to unify the Jewish community under a Western imperial umbrella — one in which multiplicity of affiliations and cultures are erased, and only the version preferred by Zionism endures.

By the early 21st century, the National Library had expanded its operations into three main divisions: the National Library of the State of Israel; the National Library of the Jewish People; and the Central Research Library of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, including four fields of study: Israeli Studies; Jewish Studies; Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies; and General Humanities.

The library achieved large cultural leaps with its collection of manuscripts in many languages. It possesses over 2,400 manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Turkish some dating as far back as the ninth century; it also owns an exclusive collection of 1,186 manuscripts from the Islamic world, over 630 Arabic manuscripts obtained by various means enhancing its status as a central cultural-academic institution in the region.

Recycling History on Stolen Shelves

The feverish effort to assume culture, import history, and plant literature into the Jewish body did not stop at the 1948 Nakba or the 1967 setback. It went beyond after the looting of Palestinian libraries and institutions. Museums in the Middle East that saw wars and conflict have also been targeted including Syrian museums. Multiple accounts indicate that Jewish manuscripts from Syria were stolen by deceit, including intelligence operations via agents. These include manuscripts known as the “Damascus Crowns.”

These manuscripts were smuggled from Syria in 1993 in an operation carried out by Mossad in cooperation with Syrian Jewish activist Rabbi Abraham Hamra. Israelis boast about the operation, which was conducted with help from a Canadian diplomat who carried one of the crowns in a black plastic bag.

In 2020, Israeli courts confirmed the theft by ruling that the manuscripts should not be returned, considering them “treasures of the Jewish people, of historical, religious, and national importance,” and that the best way to preserve them is for them to remain in the National Library under public guardianship.

The looting of Iraqi museums also fits into this recurrent pattern. Manuscripts and documents from Iraq suffered widespread looting during the U.S. invasion in 2003. It is estimated by specialists that the National Library of Israel, which holds over 100,000 books and 2,000 Islamic manuscripts, obtained a significant portion of them through thefts from the Central Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, with support from the U.S. military.

Israeli statements revealed that trafficking of these manuscripts passed through Kurdistan and Amman on route to Israel. Among the most important stolen items is a rare Torah known as “the Iraqi version of the Old Testament scrolls,” written with concentrated pomegranate juice on deer skin. This version was once under U.S. custody before later surfacing in Israel.

These cultural appropriation operations have not been considered a weakness or deficit by Israel; instead, they have been legitimized by official legislation. One example is the National Library Law passed by the Knesset in 2007, which redefined the goals and mission of the library, centered on “collecting, preserving, and caring for heritage, knowledge, and culture,” with special emphasis on the land and State of Israel and the Jewish people embodying the Zionist notion of the “people of the Book.”

In 2010, the National Library adopted a new approach aimed at strengthening its role as a central scientific and cultural research hub in the Middle East. To achieve this it launched a massive digitization project in 2012 to image, catalog, and classify tens of thousands of rare Arabic books and manuscripts; this project was financed by the European Union.

This allowed the library to control Arabic-language digital search results, thus surpassing all Arab libraries in archiving old and modern books.

In 2020, the account “Israel in Arabic” of the Israeli Foreign Ministry stirred controversy by announcing that the National Library in occupied Jerusalem had acquired the digital archive of the Egyptian Al‑Ahram newspaper via a deal described as dubious, involving a sale by the chairman of Al‑Ahram to an American company called East View, which provides research and classified document services raising widespread resentment for letting go of this Egyptian cultural heritage to foreign and non‑Egyptian hands.

It was later revealed that the National Library holds a large collection of Arabic manuscripts with ambiguous sources. In 2017 the library declared that it contains over 2,400 Arabic manuscripts, among them 100 rare Qur’anic manuscripts, but refused to disclose how it obtained them.

Among these are extremely rare Qur’ans the earliest of which dates to the ninth century (3rd century Hijri), such as one written in Kufic script, one from Morocco dating to the eleventh Hijri century, and others raising questions about their provenance.

Cultural dispossession did not end there but continued repeatedly, especially during wars on Gaza. The occupation targeted libraries, cultural institutions, and archival centers, causing systematic destruction of cultural infrastructure. Despite that, waves of cultural and intellectual theft continue clandestinely, as cultural and human heritage of Palestinians is perpetually looted.

Meanwhile, the National Library of Israel’s holdings grew to more than 4.5 million books, 2.5 million images, archives including over 106,000 newspapers and periodicals, over 600,000 manuscripts, and 12,000 map cementing its status as a focal institution in the Zionist project.

The library moved into a new building in early 2023, located between the Knesset and the Israel Museum, in architectural design reflecting philosophy of expansion and domination that is central to the Zionist project.

Yet history is broader than what can be stolen, and memory greater than what can be erased or monopolized. The expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians in 1948 constituted a human calamity but it did not succeed in breaking the dream of return one day.