The Volga Tatars have lived under Russian domination for more than fifteen generations, the longest such relationship with a colonial power of any Muslim-majority community in the world. Despite continuous assaults—including attempts to strip them of their identity—they have rarely risen in rebellion.

Even during the Soviet era and its aftermath, the Volga Tatars followed a path of quiet endurance, accepting their reality and making compromises that have steadily eroded their cultural identity. Today, their survival as a community faces a rapid and alarming decline.

This report is part of our special series "The Lands of Islam in Russia," which explores the history of Siberia and the North Caucasus republics, including Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, as well as the republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. These are predominantly Muslim regions within Russia, home to roughly 25 million people.

Place and Identity

The Republic of Tatarstan derives its name from the Tatar ethnic group and the Persian suffix "-stan," meaning land or country. It lies at the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers in eastern Russia, covering an area of about 70,000 square kilometers. It is bordered by four other Russian federal republics: Bashkortostan to the east, Udmurtia to the north, Mari El to the northwest, and Chuvashia to the west.

Its capital, Kazan, is over 1,000 years old, situated atop fertile, verdant hills. Archeological evidence suggests that Kazan predates Russia's major cities—Moscow and Saint Petersburg—by centuries.

With a population of 5.5 million, the Tatars are the second-largest ethnic group in the Russian Federation. However, they do not all reside in Tatarstan. Many were forcibly relocated by Russian authorities to different areas.

The largest concentration of Tatars today is in eastern Tatarstan, home to four million people and a demographic blend of Tatars and Russians. Yet Russians always enjoy the backing of the central government in Moscow.

Most Tatars are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school and speak a language rooted in ancient Turkic. Today, they face a dual threat: one of cultural erasure through Russification, and another of demographic manipulation in their ancestral lands.

The Volga Bulgars and Tatar Origins

Following centuries of migration from Central Asia to Europe, a Turkic-speaking ethnic group from the Black Sea steppes eventually settled in the central Volga region. Initially pagan, they established a civilization and a state on the Volga River known as the Bulgar State.

Historical and archeological evidence points to a highly organized and well-governed society that gradually absorbed various ethnic groups, including Bulgars, Finns, Varangians, and Eastern Slavs.

Islam reached the Bulgar State in the early 10th century through Muslim traders. The Bulgars voluntarily adopted Islam and replaced their old Turkic script with the Arabic alphabet. Their ruler, Almış ibn Yiltawar, sent an envoy to the Abbasid caliph, Ja'far al-Muqtadir, requesting a delegation of scholars to educate his people in Islam.

In 922 CE, the Abbasid Caliphate officially recognized the Bulgars as a Muslim land, dispatching a diplomatic mission led by Ahmad ibn Fadlan. Both Ibn Fadlan and al-Masudi refer to the state as "al-Saqaliba."

At its peak, the Bulgar State witnessed the decline of the Eastern Slavic principalities. In 1164, the Bulgars clashed with the Eastern Slavic army. Over the next few decades, they increasingly faced military threats from the west. By the early 13th century, under Russian pressure, they moved their capital from Bulgar to Bilär.

In September 1223, near Samara in southeastern Russia, Genghis Khan's forces, led by his general Oran, clashed with the Volga Bulgars but were defeated. However, in 1235, the Mongols returned with a massive army under Batu Khan and conquered the Bulgar lands, then embroiled in internal strife.

Though the Bulgar State fell under Mongol rule, much of its society and culture survived. In 1242, Batu Khan established the Golden Horde, and after his death, his brother Berke Khan succeeded him. During Berke's rule (until 1267), most of the Golden Horde converted to Islam.

The new state’s domain stretched from the Arctic Ocean to Azerbaijan, and from Turkestan and central Siberia to Poland and Hungary, blending Islamic Bulgar traditions with Mongol Tatar elements.

The origins of the modern Tatars remain a subject of debate. Are they the direct descendants of the Islamic Bulgar state in the central Volga, or of the Mongol Tatars? Genetic analysis shows Volga Tatars have primarily Eurasian Turkic and Caucasian ancestry, not Eastern Eurasian.

Today, both Tatars and Chuvash identify strongly with the Bulgar heritage. Despite the Russian-imposed name "Tatars," some modern Tatars prefer the terms "Kazan Turks" or "Bulgars."

The Kazan Khanate

In the 1430s, Ulugh Muhammad, a khan of the Golden Horde, seized the Bulgar fortress of Kazan and declared independence amid ongoing power struggles. He became the first ruler of the Kazan Khanate (1438–1445), making Kazan its capital.

Despite political turmoil stoked by Moscow and the Crimean Khanate, Kazan thrived for over a century. Its mosques, markets, crafts, and industries, especially leather and furniture making, flourished. Strategically located, it served as a key trade hub linking East and West.

Kazan’s growing prominence made it a target for Moscow. The khanate’s army successfully repelled multiple attacks, including from other rival khanates like Sarai, Astrakhan, and Sibir. Its military spending reflected a robust economy.

By the early 16th century, Kazan began to weaken. Internal disputes among its rulers fatally fragmented their power. Unlike the Crimean Khanate, which received Ottoman support, Kazan lacked strong external allies.

Between 1438 and 1552, Kazan saw no fewer than 15 khans take power, leading to chronic succession crises. This instability allowed Russia to meddle continually. The failure of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Crimea to form a united front left them vulnerable to Moscow.

Imperial Dreams: A Past That Won’t Fade

In his book A History of Tatarstan, historian Kees Boterbloem describes the 1552 Russian conquest of Kazan as a geopolitical turning point. It transformed Moscow into a global power and marked the first Orthodox Christian victory over Islam since the fall of Constantinople.

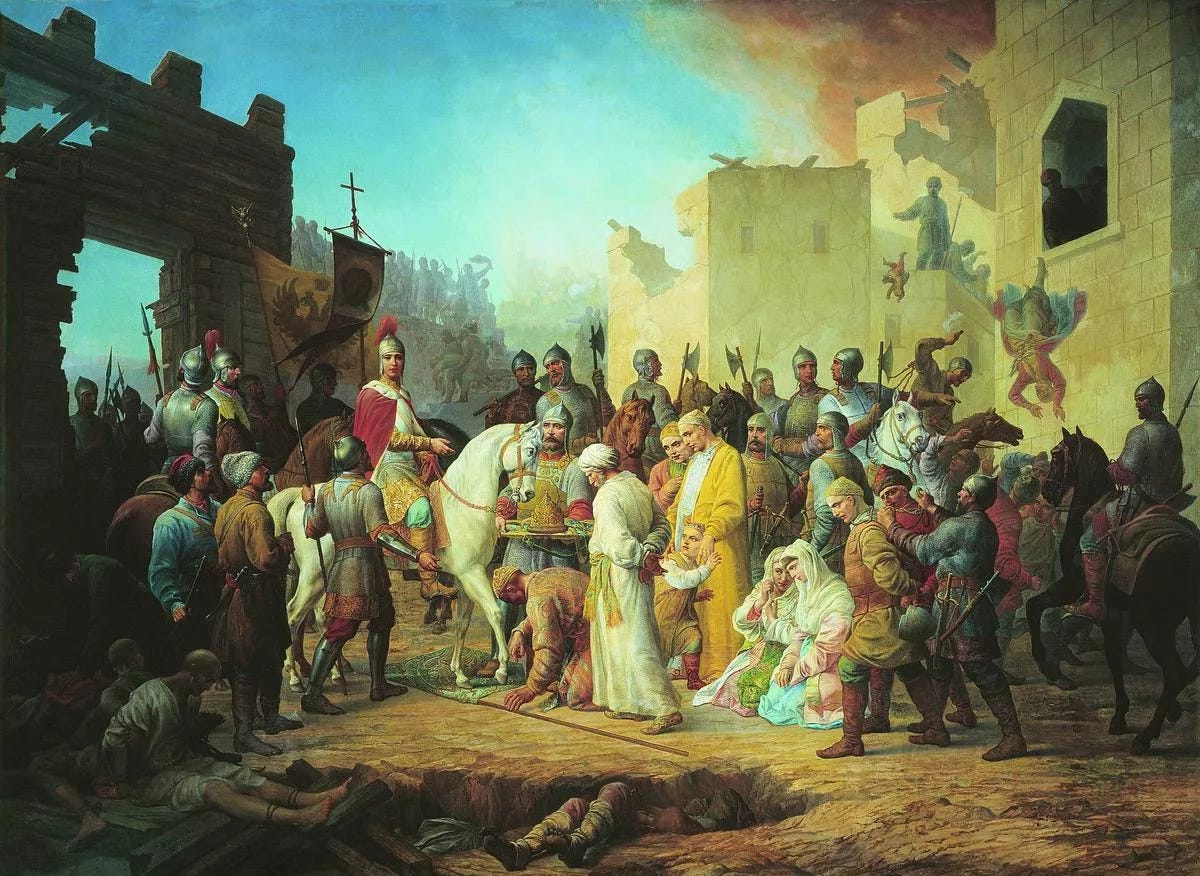

After a series of wars, Tsar Ivan IV launched a final, massive assault. His strategy involved encircling Kazan by controlling all its river routes and establishing a fortress at the mouth of the Sviaga River. In 1551, the newly built fortress at Sviyazhsk became the staging ground for a devastating siege.

Ivan led an army of 150,000 men against Kazan’s 63,000 defenders. The Russians had superior artillery, forcing the Tatars to remain behind their city walls. After 41 days of siege, a key defensive tower collapsed, and Russian troops poured in.

Though the khan was pardoned after surrendering, street battles continued. Muslim clerics and students, led by the Sufi master Syed Qol Sharif, fought to the bitter end.

Russian forces showed no mercy, slaughtering civilians indiscriminately. According to Boterbloem, Ivan’s army in 1552 was more brutal than Batu Khan’s forces three centuries earlier.

Following the conquest, Slavic settlers moved into Kazan, while surviving Muslims were banished to a suburb called Posad. Religious sites were demolished or converted into Orthodox churches. Only the Soyembika Tower was preserved—as a stark warning to any who dared dream of Kazan’s Islamic revival.

By 1558, resistance was crushed. Some Tatars later returned to Kazan but were forbidden from living inside the kremlin walls. Many Tatar towns vanished, and Tatar author lamented, “After 1552, Islam became the religion of the villages.”

Renewed Oppression: Reconstructing the Tatars

After Kazan’s fall, Christianization efforts began in earnest. In 1565, forced baptisms were implemented. By the 1590s, Orthodox priests complained to Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich that the new converts were skipping church and not wearing crosses.

In 1593, Fyodor ordered the torture and execution of Muslims unwilling to convert. Mosques were destroyed, yet Tatars continued to build secret ones.

During the brief reign of Sophia (1682–1689), Christianization halted, and Tatars rebuilt mosques. However, in the early 1700s, conversion became mandatory again. Tatar elites who wished to retain land and status had to force their Muslim subjects to convert.

Peter the Great’s daughter Elizabeth (r. 1740–1762) aggressively renewed conversion campaigns. A 1742 decree demolished 418 of 536 mosques in Kazan and banned new ones.

Catherine the Great reversed course somewhat. To avoid unrest, she allowed limited religious freedom, sanctioned Quran printing in Saint Petersburg in 1786, and appointed a Muslim mufti—Muhammad Jan Khusainov—in 1788. But this leniency came at a price: Tatars had to pay taxes and pledge loyalty and military service.

Later, Alexander II (r. 1855–1881) abandoned Catherine’s approach, reinstating Russian-language mandates and promoting conversion to Orthodoxy.

The Fall of the Tsars: Soviet Tatarstan

By 1914, the Tatar nationalist movement was still nascent. Some favored a distinct Tatar identity, others an Islamic internationalism, and some a pan-Turkic ethnic unity.

Tatars were conscripted into the Tsarist army for World War I. After the revolution, Lenin and the Bolsheviks promised justice and autonomy, which won the support of prominent Tatar figure Sultan Galiyev.

For a brief time, a Tatar-Bashkir republic, known as "Idel-Ural," was declared. Its influence was limited to Tatar neighborhoods in Kazan.

By 1920, the Bolsheviks abandoned promises of self-determination. Stalin disbanded Idel-Ural and created a much smaller Tatar republic—Tatarstan—subordinate to Russia.

The revolution dramatically altered Tatar life. Islamic councils were dismantled, and Tatars were forced to conform to Soviet ideology.

An Empty Shell: Post-Soviet Tatarstan

The early 1990s brought a surge of separatist sentiment. In a 1992 referendum, over 60% of voters supported independence, despite Russian tank drills along Tatarstan’s borders.

Soon after, President Mintimer Shaimiev signed a special autonomy agreement with Moscow. While it granted Tatarstan control over taxes and resources, its effects were weakened by Russia’s wars in Chechnya.

Shaimiev worked to revive Tatar education and culture, but under Vladimir Putin, regional autonomy has steadily eroded. Putin forced Tatarstan to revise its constitution to align with federal laws.

Tatar officials lament linguistic inequality: all Tatars must speak Russian, but few Russians learn Tatar. To address this, Tatarstan mandated Tatar language and history classes. Yet between 2007 and 2009, 111 Tatar schools were shut down.

A 2009 law required Tatar students to pass Russian exams for university. In 2016, Kazan University closed its Tatar language and history faculty. Plans for a national Tatar university stalled.

Today, Russian is the main language even in Tatar Islamic schools. In 2017, Tatar was removed from the public school curriculum—a devastating blow to cultural survival.

Volga Tatars now must share everything with Russians, including rights they can no longer fully exercise. Religious freedoms are tightly regulated, and even "religious clothing" is banned in public institutions.

Moscow continues to erase Tatar collective memory. In 2021, it banned “Remembrance Day,” commemorating the 1552 fall of Kazan. This defied a 2020 Tatarstan court ruling deeming the ban illegal.

In 2022, Putin stripped Tatarstan’s president of his title. Now only Moscow can nominate candidates for the post. Although many Tatars disapprove of current leader Rustam Minnikhanov’s deference to the Kremlin, they still see him as a final line of defense.

In the end, the dream of an independent Tatarstan seems increasingly illusory. The ancient culture of the Volga Tatars, long under siege, now faces its most aggressive threat yet: rapid Russification and cultural extinction.