Among the many international positions backing Israel in its war on Gaza, Germany’s official stance stands out as uniquely unwavering. It is a position that reveals profound historical, psychological, and political dynamics rooted in Germany’s past and its post-war identity.

There is near-total consensus in the German Bundestag—from the far right to the far left—on supporting Israel. Media coverage follows suit, almost uniformly embracing the Israeli narrative while discrediting the Palestinian perspective with striking bias. Critics of this narrative are frequently smeared with accusations of antisemitism (Antisemitismus), Jew-hatred (Judenhass), or Holocaust relativization (Relativierung des Holocaust).

Berlin has banned numerous pro-Gaza demonstrations, and those allowed have faced intense media condemnation. Meanwhile, high-ranking politicians have joined rallies in support of Israel. Many Arabs in Germany, while aware of the country's pro-Israel stance, have been shocked by the scale and fervor of its partiality. This has led many to ask a simple but profound question: "Why?"

Germany’s Holocaust Consciousness: A Singular Tragedy

To understand Germany's unwavering support for Israel, one must first understand how Germans view the Holocaust. The prevailing belief, not only in Germany but across much of the West, is that the Holocaust is a uniquely horrific and incomparable event. This is grounded in the "Uniqueness Thesis" — the idea that the Holocaust stands alone in history due to its scale, intent, and ideological purity.

According to this thesis, the Holocaust is incomparable because Jews were targeted for extermination solely for their identity, without any strategic or political aim. As a result, antisemitism is seen not merely as one form of racism among others, but as a distinct and uniquely dangerous ideology.

Opposing this is the "Continuity Thesis," which places the Holocaust within a broader historical context of systemic violence, colonialism, and racism. This view examines structural causes behind mass atrocities and sees the Holocaust not as an aberration, but as a particularly horrific node in a larger historical pattern.

Critics of the Uniqueness Thesis argue that it creates a moral hierarchy of suffering, privileging Jewish victimhood above others.

Shame and the Construction of Modern German Identity

Lara Fricke, a German doctoral researcher, explores these tensions in her paper Insisting on Uniqueness. She identifies two emotions at the heart of Germany's relationship to the Holocaust: shame and guilt.

Shame arises when a person fails to live up to their own values and feels exposed before an external audience. Over time, this collective shame became embedded in the new German identity. In an effort to overcome it, Germans began to derive pride from their renunciation of Nazism and their commitment to Holocaust remembrance.

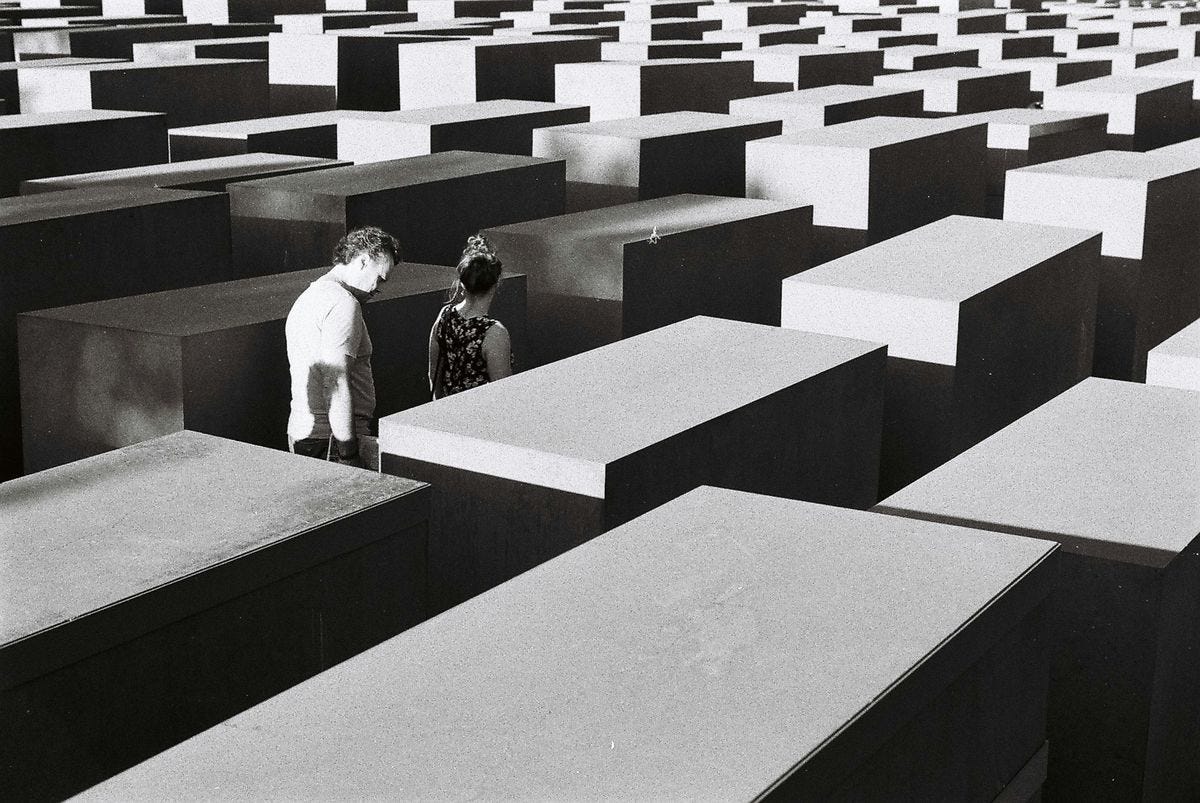

Germany institutionalized this transformation through what is known as Erinnerungskultur (culture of remembrance), a set of commemorative practices that honor Holocaust victims. Yet, because shame is socially dependent, overcoming it requires acknowledgment from an external audience: the global community, Western allies, and above all, Israel.

This creates a fragile identity structure. Any critique of Israel, particularly from Palestinians, is perceived as a threat to Germany’s hard-won moral redemption.

Guilt and Identification with the Perpetrator

Guilt differs from shame in that it stems from internal moral conviction. It does not require witnesses but demands personal accountability. Collective guilt, however, only forms when a group identifies with the perpetrators of a crime. In Germany, many feel a psychological link to their Nazi past and therefore carry a sense of inherited guilt.

This is why Germans often feel compelled to constantly denounce Nazism. Ironically, such repeated disavowals may indicate a subconscious identification with the perpetrator. If Germans truly felt detached from Nazism, they would not feel the need to continuously renounce it.

This dynamic mirrors experiences in other contexts. For example, when ISIS committed atrocities, some demanded that Muslims publicly and repeatedly condemn the group, despite having no connection to it. Those who complied often did so under the burden of imposed guilt, while those who didn't felt no identification with the perpetrators.

Selective Memory: The Limits of German Remembrance

Germany’s guilt has been narrowly channeled into Holocaust remembrance, often at the expense of acknowledging other crimes—especially those related to its colonial past. By maintaining the uniqueness of the Holocaust, Germany effectively absolves itself of further responsibility.

Support for Israel becomes a political and psychological mechanism to alleviate guilt. But Palestinian narratives, which frame Israel as a settler-colonial state, expose the continuity of colonial injustice—something Germany has yet to reckon with. Consequently, Palestinian voices, and even Jewish ones critical of Israel, are often silenced.

The Utility of the Uniqueness Thesis

Fricke’s paper identifies three key functions of the Uniqueness Thesis:

Preserving the West’s self-image. It portrays the Holocaust as an anomaly in an otherwise enlightened Western history.

Avoiding systemic change. By isolating the Holocaust, Germany sidesteps a broader reckoning with colonialism and systemic racism.

Sustaining national pride. Remembrance becomes a tool to transform shame into pride and maintain a coherent national identity.

Psychological Defense Mechanisms: Reaction Formation and Projection

These attitudes are reinforced by unconscious psychological mechanisms. One is reaction formation: when people overcompensate to conceal forbidden or shameful impulses. Some Germans may harbor unconscious antisemitic feelings, which they repress through excessive, unquestioning support for Israel. This behavior infantilizes Israelis by denying them moral agency.

Another mechanism is projection: attributing one’s own unacceptable thoughts or feelings to others. Some Palestinians in Germany say they feel punished for the Holocaust, accused of antisemitism for crimes they did not commit. This, they argue, reflects Germany’s unprocessed guilt.

The Misuse of Antisemitism

Importantly, antisemitism is historically a European phenomenon, deeply rooted in Christian Europe. In contrast, there is no equivalent legacy of Jewish persecution in Islamic history. Jewish communities lived for centuries in Arab and Muslim lands without state-sponsored extermination.

Thus, while anti-Jewish sentiment among some Arabs today exists, it is largely a modern reaction to the policies and violence of the Israeli state. Conflating this with European antisemitism distorts history and serves political ends.

State Policy and Political Consensus

Germany’s state apparatus actively shapes public opinion. Its educational system repeatedly emphasizes the Holocaust and often presents Israel as a model democracy. School trips to Holocaust memorials are common. Even language courses for immigrants highlight Holocaust history.

The political consensus is striking. Support for Israel is one of the few issues that unites all parties in the Bundestag. Media outlets across the political spectrum echo the official line, including publicly funded institutions that are theoretically independent. Such unanimity suggests top-down enforcement, not spontaneous public consensus.

Chancellor Angela Merkel was the first to describe support for Israel as a Staatsräson (reason of state)—a core national interest that supersedes even domestic concerns.

A Divided Public

Despite the state's position, the German public is more ambivalent. A 2012 poll found that only 33% of Germans believed their country had a special responsibility toward Israel. A 2014 government report found that 55% of Germans resented being constantly reminded of Nazi crimes. The report labeled this resentment a form of antisemitism.

Germany’s support for Israel is at times more zealous than that of many Jewish communities. Jews critical of Israeli policy face the same suppression as non-Jews. Yet the state continues to promote the idea that Israel speaks for all Jews, despite growing dissent among Jewish voices.

In truth, policies framed as protecting Jews often aim to protect Israel. Political leaders dress these policies in moral language, but their real objective is geopolitical.

Germany, the United States, and Strategic Interests

The United States also offers unconditional support to Israel—not out of guilt, but strategic interest. In 1986, then-Senator Joe Biden declared that if Israel didn’t exist, the U.S. would have to invent it to protect its interests in the Middle East.

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier echoed this logic in a 2023 speech, thanking Israel for its reconciliation, which he said enabled Germany to rejoin the international community.

Germany’s support for Israel helped rehabilitate its image after World War II. As the defeated instigator of the war, it was eager to signal loyalty to the Western bloc. Backing Israel, the West’s colonial outpost in the Middle East, became a way to cleanse its reputation.

Unlike the British or French, who emerged victorious and retained their global stature, Germany’s identity was shattered. Supporting Israel offered a path to moral rehabilitation, even if it did not stem from deep ethical transformation.

This is not a call for Germans to avoid accountability for Nazi crimes. Quite the opposite: Germans—alongside the British, French, Spanish, Italians, Belgians, and Americans—must reckon with both their past and present injustices.

What we see in Germany, however, is a selective reckoning shaped by geopolitical subordination to the United States and postwar anxieties. Western leaders repeatedly declare that "Israel has the right to defend itself"—a statement that, if truly self-evident, would not need constant repetition.

The reason for such insistence is clear: Israel is the last surviving colonial outpost of the Western order in the Middle East. This alone explains much of the West’s exceptional treatment of Israel’s actions, and its refusal to extend the same moral standards to others.