“Our border passes, and stops where the Jewish plow lastly plows” — this phrase, recently echoed by Israeli analysts, was not a passing justification for the military and settlement expansion that has reached southern Syria, including the summit of Mount Hermon and nearby Syrian Arab villages and towns.

Rather, the phrase embodies a profound influence left by Joseph Trumpeldor, founder of the “Zion Mule Corps,” on the formation of the Israeli mindset, a legacy adopted by settler groups today in mobilizing and rallying support for expansion projects across both the West Bank, Syria, and Lebanon.

From Zionist groups like “Hilltop Youth” and “Price Tag,” which attack Palestinian towns in the West Bank and burn farms and property, to the group “Ori Tzafon” promoting settlement in Lebanon through architectural plans and children’s stories, and even the settler “Chabad Hasidim,” which recently launched a new settlement core in the occupied Golan.

All these groups reflect Trumpeldor’s thinking — the founding father of the first Zionist military nucleus, close friend of Vladimir Jabotinsky (originator of the “Iron Wall” theory). From those ideas came the notion of creating a Zionist army that fought global wars in many regions, before transforming into organized militias targeting Palestinians by forced displacement, settlement, and even extermination.

In our “Civil Settlement” dossier, we again highlight another component of the Zionist support network, which contributed to the establishment of the Occupation state and reinforcing its political, economic, regional, and cultural survival.

This time we reveal the early military roots of the Zionist emergence, and the stages of its evolution that transformed the “Mule Corps” into a complete army supported by advanced equipment and self‑arming capabilities. A force that carried out operations to erase Palestine’s indigenous population, establishing a renewed colonial settler approach, expanding with every opportunity available on the Palestinian ground.

The Zion Mule Corps (40)

In the Qubari camps and outskirts of Alexandria in Egypt, more than 12,000 Jews who had been forced to leave Palestine under the Ottoman order of expulsion settled. This area became their refuge, along with other Western communities who chose Alexandria to settle amid the great upheavals sweeping Europe at the start of World War I, followed by economic decline that drove many to seek security and livelihood elsewhere.

Among them was Joseph Trumpeldor, a former officer in the Russian army, who served on the Japanese front in 1905. Later, he moved to Palestine, joining the first kibbutz established there, “Degania”, in 1910. He then became a member of the first Jewish guard faction known as “Hashomer”, the security faction which caught the attention of Jamal Pasha, the supreme Ottoman commander in Palestine and Syria, especially after acts implicating him in operations against the Ottoman presence in Palestine.

That discovery led Jamal Pasha to take harsh measures: imprisoning many Jews, deporting around 18,000 of them, 12,000 of whom settled in Alexandria, among them Joseph Trumpeldor, Yitzhak Ben‑Zvi, and David Ben‑Gurion.

In Alexandria, Trumpeldor met Ze’ev Jabotinsky, who had finished law studies at an Italian university. Their relationship crystallized, as their shared awareness grew that “Zionism, as an intellectual movement, cannot flourish except by liberating Palestine from Ottoman rule.”

While Jabotinsky’s articles and press reports failed to significantly influence opinion toward his idea, Trumpeldor adopted a more pragmatic approach, eager to participate militarily alongside Britain during World War I, even if only in a subordinate support unit under British command.

To him, the most important thing was to leverage this military presence to pave the way for forming a Zionist military force within Palestine, believing that “any front hostile to the Turks will lead to Zion.”

Nevertheless, the idea did not gain much acceptance, among Jews themselves or the British. The leadership of the Zionist movement, which was still forming, faced great difficulties raising the idea of supporting British forces in the occupation of Palestine.

The British War Office ignored their proposals, while they faced strong criticism from Jewish currents that opposed the idea of individually uprooting Jews to Palestine, preferring assimilation in their countries of origin. In addition, they were vehemently opposed by left‑wing Jewish groups in Britain, who saw Zionism as a deviation from their principles.

But other factors played a role in the British Army’s acceptance of the idea: the growing political and social pressure on Jews in Russia, the rising phenomena of anti‑Semitism, led many to emigrate to Britain.

There they tried to integrate economically, but their attempts were met with indifference at both government and popular levels. Thus, their employment in the British Army became a convenient outlet for all parties.

Additionally, the Jewish National Fund, in which Jabotinsky was an important figure, played a decisive role in persuading Britain of the idea, showing an exceptional capacity to raise funds and launch campaigns. Its capital reached about 400,000 British pounds, which helped enhance the acceptance of the idea of “Jewish contribution to Brit ain’s occupation of Palestine,” especially as the movement itself supplied much of the financial support, weaponry, and soldiery.

Between Istanbul — where Jabotinsky held the post of head of the Zionist press network — and Alexandria, where Trumpeldor set about preparing men and materiel, signs of forming a Jewish legion began in 1915, after the British government agreed to recruit a limited number of Jews into its army.

At first, a military unit was formed bearing the number 40, comprising 650 Jewish mule drivers, under the British commander John Peterson, assisted by deputy Joseph Trumpeldor. Trumpeldor soon assumed command alone, giving the unit a distinctly Jewish identity: orders were issued only in Hebrew, and the Star of David within the British Lion was adopted as its official emblem, to embody the Zionist character in its military action.

The unit called the “Zion Mule Corps” did not begin operations in Palestine or its immediate environs, but performed in Asia Minor, on the Gallipoli front against the Ottomans, transporting supplies to frontline lines, supporting the British attempt to breach Ottoman defenses.

Despite the Corps’ success helping secure control over the Dardanelles straits, and its ambition to help conquer Istanbul and topple the Ottoman Empire, British military setbacks in early 1916 led to ending the Corps’ operations and its disbandment, with its members redistributed elsewhere.

The end of the Corps was not considered a failure by the Zionist movement, even though 12 of its members were killed and 5 wounded. On the contrary, its distinguished performance in support and logistical tasks, and its receiving three high military medals and a medal for distinguished conduct, in addition to its symbolic status as the first Jewish military unit organized after more than 1,800 years since the fall of the Kingdom of Judah, marked a turning point in Zionist military thought, a foundation ready for later building.

The Jewish Legion

Thanks to sustained pressure, military and political courting, the Zionist movement succeeded in persuading British military leaders to re‑establish Jewish military units to support British forces, provided their theater of operations would be Palestine and its surroundings.

Accordingly, volunteers were recruited again from Britain and Egypt, and three new Jewish military formations were founded. They were fully composed of Jews, and Hebrew was used exclusively for orders; they flew the symbol of the Menorah (the Jewish candlestick).

Between 1916 and 1917 these formations – later known as the “Jewish Legion” – were organized, starting with Battalion 38, called the “Royal Rifles Campaign,” up to Battalion 42, their numbers reaching about 6,400 recruits. Ze’ev Jabotinsky was elevated to the rank of “Officer” (or “Team Leader”) of Battalion 38, while Joseph Trumpeldor continued to lead the earlier unit (the “40th Battalion”), emphasizing its Zionist military character.

Meanwhile, Battalion 39, formed after the United States entered the war alongside Britain in January 1918, was organized by David Ben‑Gurion and Yitzhak Ben‑Zvi, composed of American Jews from the U.S., Argentina, and Canada. While most battalions were based in Egypt, the 39th Battalion trained in East Jordan.

Despite significant military preparation, that did not necessarily mean active combat in Palestine. Between 1917 and 1920, the Jewish military units did not participate in any major combat operations inside Palestine. Still, part of these units entered Palestine with British southern advances at the end of 1917, after the southern region fell under British control.

Units based east of the Jordan River suffered from malaria, causing a dramatic drop in the number of active soldiers; from roughly 800 down to about 150. As a result, these units were assigned to guard the Jordan crossings and surrounding areas. After two attempts, Battalions 38 and 39 managed to cross the river and seize control of the city of Al‑Salt, which the British General Allenby considered “a contribution to the great victory in Damascus.”

That mission was the only military operation the Jewish Legion carried out during WWI before the British completed the occupation of the whole land of Palestine. This allowed Battalions 38, 39, and 40 to station freely inside Palestine. Over time, the Jewish Legion became known as the “Yehuda Regiment,” shifting its tasks toward securing communications, supporting security, and controlling occupied locations.

By that time, the three battalions had reached about 5,000 Jewish soldiers. Faced with the urgent British need to maintain colonial expansion in other areas, the British reduced their own military deployment in Palestine in favor of expanding the Jewish military presence, which had by then reached around 15% of the total British force on the ground in Palestine.

As World War I escalated, Jewish military presence in Palestine gained great momentum and British support, and the participation of Jewish Legion members in British camps became standard. The Zionist movement took responsibility for developing these units, equipping them with arms, and renewing military expertise among their members.

Although training took place alongside British forces and there were attempts to integrate Arabs alongside them, the Jewish formations preserved a pattern of secrecy and autonomy. They remained committed to the Zionist strategic plan aiming to establish a permanent presence in Palestine, backed by military force. Accordingly, they modernized their battalions and gave each of them different names, like “The Guard,” “Self‑Defense Forces,” and “Labor Troops.”

Meanwhile, Joseph Trumpeldor returned to Russia, where he began organizing a Jewish army of between 70,000 and 100,000 recruits, aiming to reach Palestine via breaking through the Turkish front. He adhered to his basic plan of training Jewish recruits; he opened membership to all Jewish youth aged 18, and made learning Hebrew, alongside mastery of agriculture and combat, a core requirement for membership.

Ben‑Gurion and Jabotinsky moved toward unifying Jewish military efforts under a single umbrella. With the establishment of the “Histadrut” at the end of 1920, which represented the nucleus of a “Jewish national home,” the three battalions were dissolved and merged into one battalion, called the “Hebrew Battalion,” which soon became known as “Haganah,” considered by the Zionist movement the first Jewish military force independent in origin and purpose.

From Legion to Army

The transition from the Legion to the “Haganah” army was not smooth, especially between Ben‑Gurion and Jabotinsky. The latter aspired to an overt Jewish military force capable of training and recruitment, even if under British authority. By contrast, Ben‑Gurion believed secrecy and discretion should take priority, especially given that Britain, despite its promises, was cautious for fear of an Arab backlash.

The rift between Ben‑Gurion and Jabotinsky also concerned how to deal with British political positions; Ben‑Gurion thought it was important to publicly align with British policies while opposing them in secret, accepting the idea of a Jewish homeland only west of the Jordan River.

Jabotinsky, on the other hand, publicly and privately urged opposing British stances and demanded inclusion of the East of Jordan in the future Jewish national home. This political and military‑strategic disagreement eventually led to a split between them in both military and political spheres.

While the fall of the Russian government undermined Trumpeldor’s project, his ideas about Jewish military volunteerism spread across Eastern and Central Europe as well as the U.S. He later returned to Palestine, where he was killed in an attack by Arab resistant fighters on the colony of Tel Hai, built on the ruins of the village of Talhah in northern Galilee, in 1920.

In his honor, Jabotinsky in 1923 founded the “Beitar Trumpeldor” (Betar) organization, which called for a “Greater Israel” characterized by Zionism neither socialist nor liberal, grounded in strict military training and recruitment. Its emblem included a map of Palestine and Jordan, with a rifle circled by the slogan “Rak Koch” (“Only [and exactly] thus”).

Later the Beitar organization was known as “Irgun” or “Etzel,” which targeted both the British and Palestinians through many operations, including the infamous Deir Yassin massacre.

On the other hand, supported by the Histadrut, Ben‑Gurion moved to transform the “Haganah” into a Jewish Army, with the objective of using it later as a political and military force. However, his efforts did not succeed in recruiting more than 3,800 at that time, because the Jewish minority in the kibbutzim and agricultural yishuvim were unwilling to participate in military action, in addition to the British cautious stance toward Arab reaction.

The situation remained the same until 1931, when the threat of Nazi Germany grew, which drove more Jewish immigrants to Palestine, enhancing the power of the Zionist movement. It began holding public conferences affirming its determination to establish a Jewish state and government on the land of Palestine. Then with the outbreak of the Palestinian Great Revolt in 1936, the Jewish Army’s privileges expanded.

British officers began relying more heavily on Jewish military force to help suppress the Palestinian revolt, and agreed to establish pure Jewish regulatory groups to protect Jewish settlements. Meanwhile, Zionist political and military leaders played the British and American hands, using available opportunities to develop the Jewish army, supported by political decisions that strengthened the Zionist movement’s power.

Thus the Jewish Army emerged publicly through the “Jewish Settlements Police,” which continued engaging in settler expansion and attacking Arab towns and villages, driven by the vision of its leader, Ben‑Gurion, who was comfortable with Jewish political and military superiority, considering that the Zionist movement had emerged from the danger zone, and that the relationship with the Arabs could only be defined through military, not political, resolution.

By the end of 1939, the Jewish Army – including Haganah and the Jewish Settlements Police – numbered over 67,000 recruits, spread across 270 settlement points, receiving training in collaboration with the Jewish Agency, and equipped with advanced hardware totaling over 4,500 rifles, 10,000 pistols, and 230 machine guns.

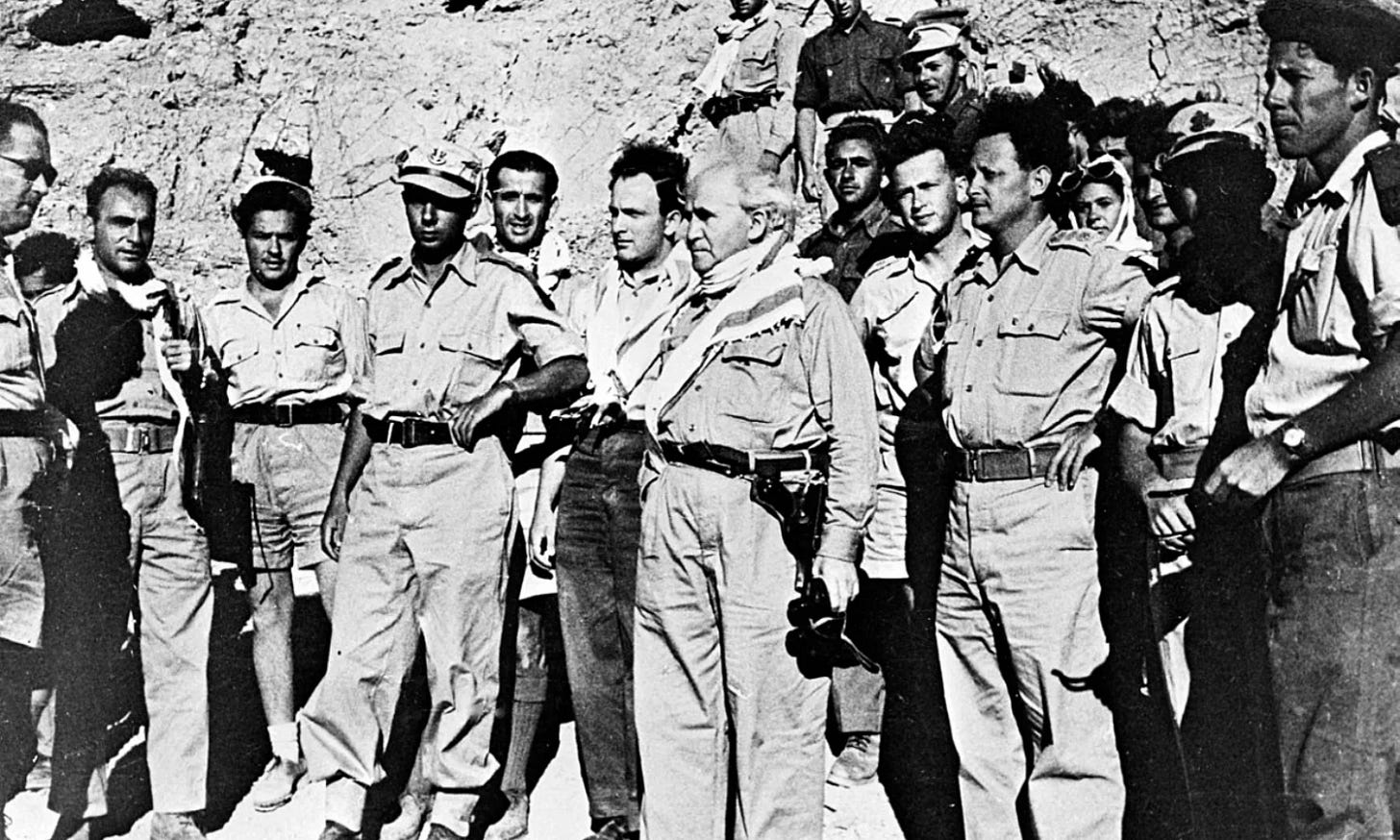

The Polish and British armies supported the Jewish Army with more than 10,000 hand grenades, two million cartridges, 2,750 Polish rifles, 7,860 British rifles, plus 96 machine guns. Among the most prominent fighters in that period were Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Rabin, and Yigal Allon.

By the end of the 1930s, the Jewish Army introduced a compulsory training program for Jewish males and females between fourteen and seventeen years of age for preliminary military training, including medical service and defense mechanisms. This program soon expanded to cover all Jewish immigrants, including training doctors for military medical service and involving scientists in developing the Jewish military industry.

On the Footsteps of War Zionism Flourished

Not long after, the drums of the Second World War sounded, bringing with them a greater American role, a decline in British power, and news of the Holocaust and German‑Arab cooperation. Amid these shifts the Jewish Army achieved a qualitative leap in its history.

This shift began with reactivating the Jewish Legion through service to Britain in its war effort, which helped enlarge the political and military gains of the Zionist project, then ambitions expanded toward Jewish independence, eventually tilting toward American support.

A British Jewish Committee formed to press both the British and American governments to expand the capabilities of the Jewish Army. At the same time, Chaim Weizmann, David Ben‑Gurion, and Jabotinsky worked to rally American Jewish support via Zionist‑American organizations such as the “Zionist Emergency Committee” and “American Friends,” aiming to mobilize U.S. public opinion to back the Jewish Army and mitigate fears of dual loyalty in the U.S., and concerns over antisemitism in Europe.

While Jabotinsky died of a heart attack while in the U.S., his followers, and meanwhile Ben‑Gurion and Weizmann, expanded the military infrastructure of the Jewish Army, preparing it to face both Palestinians and Arabs. They also managed to smuggle advanced weapons valued at over $20 million from the U.S. without detection by British authorities.

With Harry Truman coming to the U.S. presidency in 1945, sympathetic to the Zionist movement, British power diminishing after WWII, and the Axis powers’ early successes, plus the active support from Ha‑Haganah for the Allies, the Jewish Army reached an ideal political‑military position.

In late 1944, Britain announced formation of a Jewish brigade within the British Army, where this brigade fought across forty European fronts, carried its own Jewish flag, and its personnel wore distinctive uniforms — granting the recruits a “great satisfaction” by distinguishing them from other ethnicities in the war.

As a result of a Churchill decision, three additional Jewish military wings were formed: first, a tank and artillery brigade with about 6,000 Jewish soldiers; second, the “Palmach” unit, which enjoyed greater operational freedom where British forces were stationed; and third, a Jewish reserve arm. Total Jewish soldiers in these wings exceeded 24,000.

Meanwhile, the British increasingly relied on Jewish military factories that profoundly helped supply war materiel: producing over three million anti‑personnel mines and seven million steel military containers. The military production value for the British army exceeded £33 million sterling.

By mid‑1945, the budget for the Haganah organization had reached approximately 7.5 million U.S. dollars, and the Jewish military industry expanded via purchasing wartime surplus weapons and equipment from the Allies, then recycling them. Hundreds of tons of Allied military materiel were shipped to Palestine at cheap prices, and new weapons were smuggled through this policy at low cost into Zionist hands.

By the end of WWII, the Zionist movement had secured strong U.S. promises supporting the suppression of any Palestinian resistance opposing the Biltmore Program. The British White Paper was undermined, pledges for a Jewish national home were made via a Jewish military force under Jewish command and Jewish flag, and oversight by international authority.

In the three years preceding the Nakba (Catastrophe), Haganah, Irgun, and the Palmach carried out attacks against Arabs and British forces, responding to British political decisions that rejected full Jewish control of Palestine, and opposing international partition plans. Conflict between the British Mandate authorities and the Zionist movement intensified, especially after the British army occupied the Jewish Agency offices in 1946, and the King David Hotel was bombed the same year.

Between late 1947 and mid‑1948, the Jewish army, backed by the United States, launched two major offensives: the first against the British army to force its departure, the second against Palestinians to displace them from their cities and towns.

Meanwhile, Zionist political leaders approved the partition plan in order to delay Arab states’ entry into the conflict alongside Palestinians. They also struck bilateral agreements with Arab leaderships, e.g. the Be’gin‑Abu‑Udhi agreement with Jordan, coordinating military and political positions.

As the British presence gradually withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces expanded control on the ground rapidly. While Britain opposed a Palestinian state under Amin al‑Husayni’s leadership and preferred annexing remaining areas like Ramallah and Nablus to East Jordan, Zionist militias overran most of Palestine.

Supported by more than 94,500 recruits equipped with military hardware and armed with political and military backing from Britain and the U.S., as well as prior Arab‑Jewish agreements that bolstered Jewish presence, the Jewish army by mid‑May 1948 gained control over most of Palestine.

It faced only about 5,000 irregular Arab soldiers, along with a few thousand Palestinians divided between the Husayni and Nashashibi factions, amid division over waiting for Arab armies or resisting with weak, faulty arms.

In conclusion, it is important to understand that present claims about the Israeli occupation army’s superiority over Arab armies or Palestinian resistance cannot be detached from its founding, development, Western support, and the military‑political maneuvers of its leaders. These factors together established a single entity despite differences in borders and policies.

At the same time, this comparison should not be used to show incapacity or failure, but rather should rest on serious ambition both politically and militarily in confronting the occupation. Of course, the gap between the two sides will remain, maybe sometimes wider, sometimes narrower, but that does not mean stopping the constant striving to shift the comparison from the battlefield of arms and preparation to the front of belief in rights and their importance in reclaiming them.