From the earliest months of the genocidal war on Gaza, the name Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, has forcefully resurfaced; the man has moved across wide advisory circles, oscillating between the corridors of power in the United States, the Israeli occupation government, and even the office of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

Blair, who once served as the Quartet’s Middle East envoy, carries no positive legacy in Palestinian memory nor in the consciousness of the region’s peoples, for his name is linked with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and near‑absolute alignment with U.S. policies in the “War on Terror.” He is also remembered for helping derail the Second Intifada and repeatedly attempting to engineer the Palestinian internal scene to suit the occupier’s demands.

Today, Blair is presented as the foremost candidate to manage Gaza’s “day after” file, as part of a plan he played a central role in formulating. It is described as a reproduction of the “High Commissioner” concept, vesting him with supervisory powers beyond merely reconstruction: these extend into Gaza’s social and political structures.

In so doing, the current U.S. project attempts to produce a Palestinian space stripped of national character, reintegrated into a new political‑administrative dependency system aligned to international norms and Israel’s vision for the future of Palestinian governance.

Birth, Education, and Early Years

Anthony Charles Lynton Blair was born on May 6, 1953, in Edinburgh, Scotland, into an upper middle–class family. His father, Leo Charles Blair, was a prominent lawyer with political ambitions—indeed, in 1963 he nearly stood for Parliament, until a stroke left him unable to speak.

That early crisis forced the family into harsh adaptation. For young Tony, the event left a deep impression and became an implicit motivation to carry on what he perceived as his father’s “unfinished mission,” whether in law or politics.

Blair spent his early childhood in Edinburgh, but the family soon relocated to Durham, England, where he attended Shire’s (Shore?) School. In this period he showed a bold, sometimes rebellious temperament, eager to test new experiences.

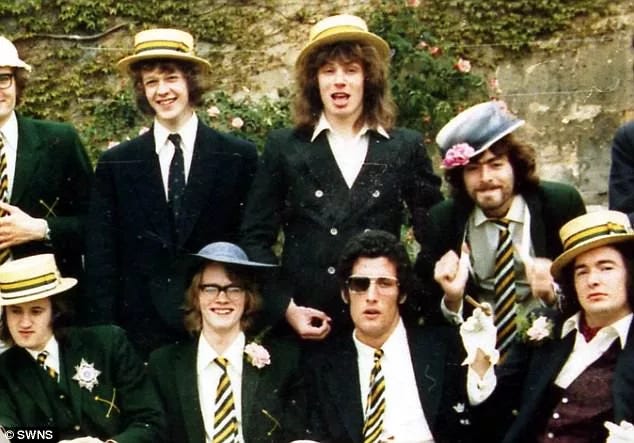

Outside academia, he loved music which became evident at Oxford, where he became lead singer of a rock band called The Ugly Rumors, performing well-known songs of the era. This small artistic venture was more than a pastime: it revealed his social flair, his capacity to connect with audiences and draw attention traits that later accompanied his political career.

In the early 1970s, Blair matriculated at St John’s College, Oxford, to study law. His university years coincided with intense intellectual and political ferment in Britain and Europe, shaping his early worldview.

He graduated in 1975 with a law degree, the same year his mother, Hazel Cornell Blair, died of thyroid cancer an emotionally compounded loss that pushed him toward greater seriousness in his professional life.

After graduation, Blair undertook legal training under the supervision of the Queen’s Counsel Alexander Irving, who later became a major figure in Labour politics and a political companion. Blair quickly demonstrated intellectual agility and the ability to cultivate connections in legal and political circles, and this phase served as the bridge to his entry into active politics.

On the personal front, Blair met Cherie Booth during his training herself a barrister and London School of Economics graduate and in March 1980 they married. They had four children: Euan, Nicholas, Catherine, and Leo. Beyond being his life partner, Cherie played an influential role in his career, later emerging as a prominent barrister and judge, helping Blair interpret British public opinion and social justice issues.

Labour’s Reformer and Symbol of Right‑leaning Policies

Blair entered politics via the Labour Party in 1978, at a time when Labour was mired in internal crises and deep factional divisions, unable to return to power since the late 1970s.

Interestingly, his father had once briefly joined the Communist Party in youth before ending in the Conservative Party; Blair himself chose the opposite trajectory, rapidly establishing himself as a rising face in Labour.

His first attempt to enter Parliament in 1982, for Beaconsfield, failed but it raised his visibility. A year later he won the safe Labour seat of Sedgefield (near Durham), beginning his lengthy parliamentary career.

During that time, the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher dominated governance, while Labour under Neil Kinnock attempted to regroup. Kinnock offered early backing to Blair, clearing the way for him into key positions within the party.

From the mid‑1980s into the early 1990s, Blair held successive shadow cabinet roles—spokesman on economy and treasury, trade and industry, and later Shadow Home Office. Through these roles he built a reputation as a hard worker capable of crafting a hybrid message: merging traditional left rhetoric with reformist appeals that reached new voter segments.

In 1992, after Labour lost again, Kinnock resigned. John Smith succeeded him, but Smith died unexpectedly in 1994, paving the way for Blair’s meteoric rise. Blair became Labour leader, the youngest in the party’s history.

From the outset of his leadership, he launched the “New Labour” project, a reformist current that broke from the dominance of the old left in the party. He rewrote the party constitution, scrapped Clause IV (which had called for nationalization of production), a radical shift many saw as a betrayal of Labour’s socialist roots yet it cleared the path for Labour’s return to power after 18 years in opposition.

Blair’s policies were marked by centrism and greater affinity with conservatives than his left wing preferred. He adopted a presidential style, more akin to a strongman leader than a constrained prime minister. He embraced free-market economics, tougher law-and-order measures, anti‑crime initiatives, and greater autonomy for local governments. In foreign policy, he aligned closely with the United States and moved closer to the European Union.

In 1997, Blair led Labour to a landslide electoral victory, ushering in a decade of governance lasting until 2007. During this period, conservatives admired him as a “right‑leaning” leader more than a typical leftist, and even David Cameron later claimed to consult him frequently. Yet his approach enraged Labour’s left, who accused him of sacrificing socialist principles for political and economic expediency.

The ultimate paradox emerged in his support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. While some argued that any British prime minister especially a conservative might have allied with the U.S., Blair’s Labour identity made the decision far more controversial. It deeply split his party and the public.

In sum, Blair cast himself as Labour’s reformer but embodied a drift toward centrism and even the right, transcending traditional party lines and tethering Britain closer than ever to the U.S.

Architect of U.S.–Led “War on Terror”

From the day of the September 11, 2001 attacks, Blair positioned himself at the heart of the U.S.’s “War on Terror,” becoming Europe’s staunchest defender of that agenda. He framed the attacks as a “declaration of war on the West,” and without reservation aligned behind President George W. Bush in Afghanistan and then the 2003 Iraq invasion.

In Iraq, Blair was integral in providing international legitimacy to the war. He urged the White House to pursue a United Nations resolution a case for Resolution 1441 in November 2002, which was later used to justify the invasion when Baghdad failed to demonstrate it had no weapons of mass destruction.

Despite opposition from 139 Labour MPs, Blair pressed ahead with support from British conservatives leading to one of the deepest party schisms in recent British history.

Later revealed documents and the Chilcot Inquiry (2016) showed that Blair’s government exaggerated Saddam Hussein’s threat and ignored warnings that the invasion would unleash regional chaos and strengthen extremist groups. (Wikipedia)

Despite this, Blair continues to defend his decisions, insisting that the world is “safer” after Saddam was overthrown—even as he acknowledges the catastrophic results: hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths and the collapse of the Iraqi state.

Though he was never criminally indicted, public perception in Britain remains blisteringly critical: many consider him a figure of duplicity. In 2022, over half a million Britons petitioned to strip his knighthood, labeling him a “war criminal.”

Today, Blair remains unrepentant. He has repeatedly said that, given the same information, he would make the same choices. He has even advocated for military action against Iran to force it to abandon its nuclear program a continuation of the same mindset that made him Europe’s most American‑aligned leader in the War on Terror.

Thus, Blair was not merely a partner in those wars, but a key architect and moral apologist. His name has become synonymous with full alignment with the American agenda—and proof of the UK’s shift from “New Labour” to a pliant Washington ally.

The Quartet, Controlling the Palestinian Resistance

After leaving the prime minister’s office in 2007, Blair did not exit the international stage: he assumed the role of Middle East envoy for the Quartet (U.S., EU, U.N., Russia), the mechanism created to promote Israeli–Palestinian peace. Though that appointment was pushed by President Bush, it bore an overtly American stamp, while the other actors played a lesser, symbolic role.

The Quartet, born amidst the Second Intifada and the U.S. invasion of Iraq, launched its 2003 “Roadmap” plan, which envisaged a temporary Palestinian state in return for Palestinian efforts against “terrorism,” while Israel would freeze settlement and withdraw from Palestinian cities.

The Roadmap soon faltered, but Blair returned in 2007 to revive the plan, deploying his authority as envoy until 2015.

Throughout his tenure, Blair was not viewed as a neutral mediator but as an executor of a policy aimed at remaking Palestinian consciousness and the internal political scene in ways compatible with Israeli demands and the Quartet’s conditions.

He concentrated on excluding forces of Palestinian resistance, preserving the Authority as a security proxy guaranteeing West Bank calm far from real political prospects. He deepened the split between Gaza and the West Bank, reinforcing isolation of Gaza and obstructing any serious national Palestinian partnership.

The Quartet’s conditions became gatekeepers for international recognition of any Palestinian unity government.

Blair also emphasized the economic pacification of Palestinians via “economic peace” initiatives, which prefigured the more expansive “Deal of the Century” later advanced by Jared Kushner under Trump. Thus, Blair’s policies formed a connective tissue between successive U.S. strategies aimed at confining Palestinian rights to minimal improvements in material conditions rather than broad political change.

Blair’s stint with the Quartet coincided with three brutal Israeli wars on Gaza (2008, 2012, 2014), during which he frequently provided diplomatic cover for Israeli arguments and framed Palestinian resistance as “incitement” or “terrorism.”

In doing so, he blurred the line between a people resisting occupation and extremist violence and in that stance, revealed his clear bias against Palestinian national identity grounded in struggle.

Though he later admitted that excluding Hamas was a “mistake,” his record as envoy is viewed by many Palestinians as a project of taming and exclusion not a serious bid for a just settlement.

“Gaza Riviera” and Investment on Rubble

Amid intensified Israeli aggression and mounting destruction in Gaza, Blair’s name again surfaced at the center of planning. Israeli press, including The Times of Israel, reported that the Netanyahu government offered Blair the post of “humanitarian coordinator in Gaza.” The Tony Blair Institute denied any formal offer, but his intense visits to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv since the war’s onset further fueled speculation that he is intimately tied to “day after” designs.

The proposals go beyond humanitarian coordination. Israel’s Channel 12 claimed Blair would become “general coordinator for voluntary displacement of Palestinians.” Though denied publicly, the Palestinian leadership saw his involvement as a war crime, and Fatah likened him to a new Balfour. The Palestinian Authority declared him persona non grata in Palestinian lands.

Perhaps the most controversial plan came in The Economist, reporting that Blair’s institute is promoting the “Gaza International Transitional Authority” (GITA). The proposal envisions a five‑year international authority running Gaza, led by a seven‑member council funded by Gulf states, initially from Al‑Arish (Egypt), before finally entering Gaza accompanied by an international force.

The idea was reportedly presented to Trump, with backing from Kushner and Netanyahu’s inner circle.

For Blair, GITA is not a mere technical proposal but an extension of his longstanding philosophy: exclude resistance, impose international guardianship, and perpetuate bureaucratic dependency over Gaza under the guise of reconstruction mirroring experiments in Kosovo and East Timor.

Polls by his team in Gaza suggest some residents might accept such oversight in return for improved living conditions. The plan is pitched as an alternative to extreme ideas of mass displacement or converting Gaza into a “resort” managed by AI systems plans floated in prior Trump proposals.

But in Palestinian consciousness, these projects echo the colonial mandates of the past—especially Britain’s legacy in Palestine. Blair’s imminent role in “New Gaza” is perceived not as peace-building but as the restoration of a disguised mandate, seeking to craft a “Gaza Riviera” on the ruins of a besieged and shattered people.