From investigative exposés to political and diplomatic scandals, through the shadowy corridors of power and palace disputes, and even into an archive that resists erasure, one particular phrase continues to echo across the Arab media landscape. It suggests a kind of dominance many Arab journalists long to possess, and reflects a relinquishing of responsibility for the content and its consequences. That phrase is: “According to Israeli media.”

No matter the context, the phrasing, or the descriptive label—whether “Hebrew media,” “Israeli sources,” or “enemy press”—what emerges from Israeli outlets has long held an allure in Arab societies. It is seen as revealing the unseen and speaking plainly about what is otherwise merely hinted at, from heads of state to the average citizen. Consequently, Israeli censors have long been cautious about what gets published—both to protect their own public and to manipulate the hearts and minds of millions across the Arab world.

This installment in the Haaretz and Sisters series offers an in-depth investigation into the history of Israeli media—or what is often referred to as the “Zionist press network.” It traces the emergence and development of these newspapers and media institutions, their military entanglements disguised as journalism, their editorial paths, and their influence over Arab minds across decades of peace accords, revolutions, wars, and shifting alliances that exposed the fragility of relying on such media narratives.

This particular section focuses on Yedioth Ahronoth: from its founding to its influence, its editorial evolution and political realignments, its ties with the military and security establishment, its internal and regional positioning, and its place in the ethical framework of journalism.

A journey through the Israeli National Library’s archives—tracking major early political, military, social, and sports milestones—reveals Yedioth Ahronoth’s coverage as a key reference for interpreting events through an Israeli lens.

This prominence stems from its early founding—before the 1948 war and the creation of a colonial Israeli state on Palestinian Arab land—as well as its contemporaneity with regional and global developments, which it consistently interpreted through an Israeli perspective that aligned with prevailing public sentiment. This editorial approach helped sustain its circulation and growth to the present day.

It dates back to the British Mandate era, amid increasing Jewish immigration and the implementation of early Zionist Congress resolutions (1897–1906), which sought to create ideological and cultural cohesion among Jewish migrants and to revive Hebrew as a modern lingua franca. Jewish libraries were established in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and historical Jewish books were imported from Russia, Germany, and across Europe. Newspapers began to emerge, promoting the ideas of settlement and migration.

Among those newspapers were HaAhd, launched in 1909 by the Zionist Office in Jaffa; Haaretz, established in 1919 as the first left-leaning daily targeting the Jewish cultural elite; Davar, founded in 1925 by Berl Katznelson to support the Histadrut and develop Zionist labor politics; and HaBoker, launched in 1935 as the official voice of the General Zionists party.

Amid this journalistic awakening and a growing hunger for Hebrew-language newspapers among Jewish immigrants, Yedioth Ahronoth appeared on September 11, 1939, introducing a populist news model built around fast, concise reporting. This was reflected in its name—“Latest News”—as well as in its format, consistent with the vision of its founder, Russian-Jewish investor Nachum Komarov.

Its inaugural headline read: “The British Launch Attack on the Western Front.” The issue, printed without any photos, was sold at the top of Herzl Street in Tel Aviv. To avoid competing directly with more established newspapers, Yedioth adopted a two-edition-per-day strategy—an afternoon and an evening version—targeting Jewish laborers at the end of their workday.

This also reflected an editorial model borrowed from London’s popular Evening News, and a strategic distancing from party affiliation—unlike the rest of the nascent Hebrew press at the time.

Still, Yedioth maintained proximity to Mapai and its founder David Ben-Gurion, who was then enjoying widespread popularity among Jewish immigrants and Histadrut workers. This proximity expanded its readership and enriched its content, though it did not translate into financial success.

Burdened by mounting debts, Komarov declared bankruptcy within a year of its launch. The paper was sold to one of his creditors—Alexander Moses, owner of the Moses Printing Press—in exchange for clearing the debt. A year later, Alexander’s son, Yehuda Moses, a rising real estate developer, took over operations. He brought in his son Noah Moses to help align the paper with the socialist values embraced in the kibbutzim.

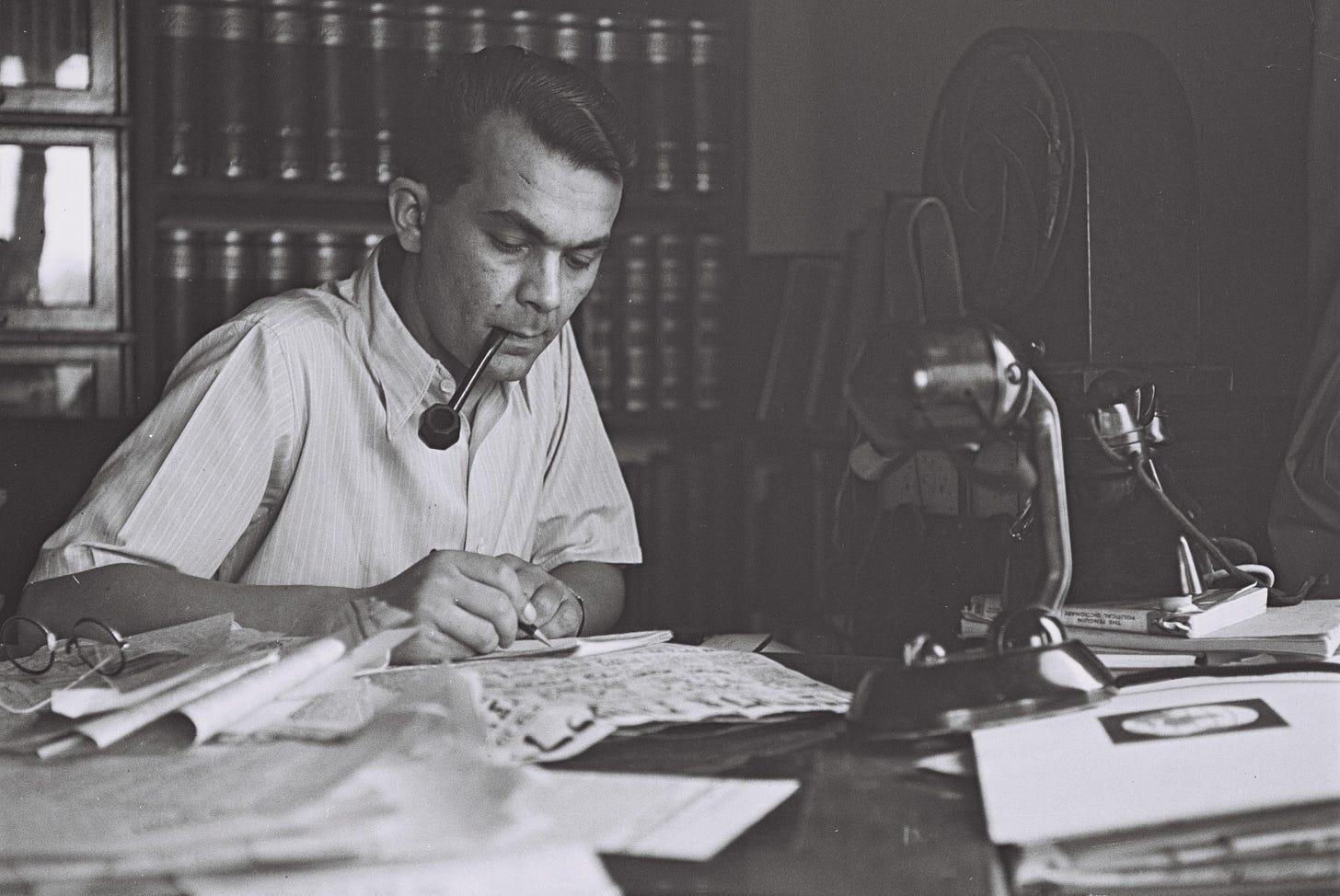

By mid-1940, leveraging his social and professional networks, Noah Moses proposed hiring Azriel Carlebach, a German-born Jewish journalist with religious and academic training, as editor-in-chief. Carlebach had migrated early to Palestine and held a PhD in law from universities in Berlin and Hamburg.

Carlebach’s appointment marked the beginning of Yedioth’s first major surge. He brought a serious editorial style, introduced variety in coverage, prioritized exclusives, and mirrored global trends in journalism. This made the paper increasingly popular, especially in Tel Aviv and its surrounding neighborhoods.

As World War II intensified, Yedioth began to outshine older publications like Davar and Haaretz, especially in its exclusive coverage of how the war affected the British Mandate, Arab-Palestinian communities, and Jewish immigrants. As political tensions mounted, the paper’s circulation occasionally reached 20,000 copies.

This growth coincided with the recruitment of additional Jewish journalists from other Hebrew and international outlets. Among them were Shalom Rosenfeld, Shmuel Schnitzer, Aviezer Golan, Yosef Vinitsky, and others.

Faced with this escalating competition, leftist parties launched additional newspapers to relieve pressure on Davar. One such effort was Hadashot HaRaf, which explicitly aimed to compete with Yedioth, though it never matched its success.

The Challenges of the “Great Coup”

Despite the rapid and substantial growth under Carlebach’s leadership, tensions escalated between him and the Moses family over editorial policy and financial decisions. The most prominent dispute came when Carlebach traveled to the United States in November 1947 to cover the United Nations vote on the partition of Palestine.

Believing the story was of immense importance, Carlebach transmitted his report via an urgent telegram—incurring high costs. When Noah Moses discovered the expenses, he was infuriated.

At the same time, Carlebach was enforcing an editorial policy that involved cutting stories that might damage his allies in the business sector. These editorial restrictions escalated tensions and ultimately led to an impasse. On the evening of February 13, Carlebach left a letter on Yehuda Moses’s desk offering to purchase the paper and warning that his resignation would jeopardize its future. When Moses rejected the offer, Carlebach resigned—and on the same day, founded a rival newspaper.

The event, known in the history of the Hebrew press as “The Great Coup,” resulted in a mass exodus of Yedioth Ahronoth’s editorial team, who joined Carlebach at his new paper: Yedioth Ma'ariv (later shortened to Ma'ariv).

This defection dealt a severe blow to Yedioth. In response, the Moses family mobilized all available resources: family members, retired Jewish journalists, unemployed professionals—all were brought in to keep the paper afloat.

Extraordinary measures were taken: family members sold the paper themselves; editors were recruited from nationalist newspapers such as HaBoker; and real estate assets were liquidated to fund printing and publishing. Profits were frozen, and even children were dispatched into the streets to yell out the paper’s name in hopes of keeping it alive in public consciousness.

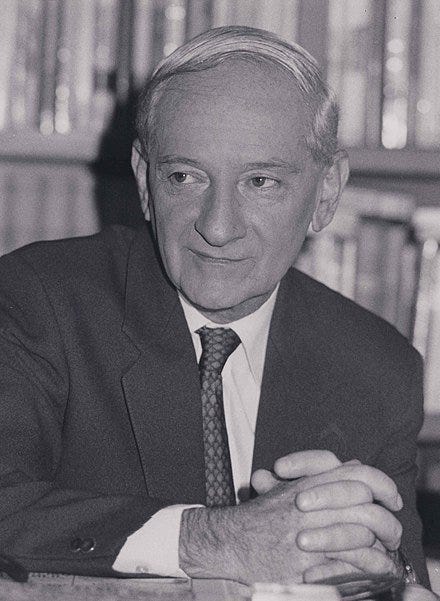

Despite the damage caused by the coup—whose effects lingered for more than two decades—Yedioth Ahronoth maintained its focus on breaking news and exclusives. Editors Dov Yudkovsky and Herzl Rosenblum emphasized diverse editorial approaches: from writing daily columns to scouting new journalistic talent, to competing with Ma’ariv through sensational tabloid-style news. Writers who managed to outperform Ma’ariv were rewarded.

By the early 1960s, the tide began to turn. Yedioth adopted a more open editorial policy, tackled pressing social issues, and aligned itself more closely with the Jewish public’s preferences—particularly in its vocal support for Israeli military operations.

The newspaper also introduced a range of temporary supplements: some focused on politics, others on satire, art, entertainment, or sports. These supplements catered to both the political left and right. One left-leaning supplement, for example, was called “The Land of Conquest.”

“The Nakba as Carnival”: A Trilogy of War, Exclusion, and Justification

Throughout its formative years—between 1939 and the early 1960s—Yedioth Ahronoth maintained a centrist editorial position that balanced its economic goals with its media messaging. The paper relayed statements and news from the British Mandate without explicitly supporting it, instead adopting the Zionist public’s prevailing view that the Mandate failed to provide adequate means for the “Jewish minority” to realize their national homeland in Palestine.

At the same time, the paper aligned itself with labor-socialist developments by covering kibbutzim and the Jewish community (Yishuv), though it never formally joined the Histadrut’s orbit—largely because owner Yehuda Moses was a capitalist liberal who rejected collective socialism.

Domestically, Yedioth promoted a Zionist-nationalist narrative that glorified war and downplayed casualties. It divided the world into “allies” and “enemies,” and its articles helped shape a public discourse that celebrated Israeli military superiority over its neighbors. This, in turn, laid the groundwork for policies excluding minority communities like the Druze, Circassians, and Christians.

Regarding Palestinians, Yedioth maintained a Zionist alignment, albeit with slightly more nuance than explicitly partisan or nationalist newspapers. Between 1947–1949, its pages overflowed with triumphalist rhetoric, using phrases like “our army,” “our weapons,” and “riot control” to describe Zionist militias. It advanced claims that Arabs had fled voluntarily and relinquished their lands.

One of the most inflammatory examples was a piece by Asaf Gefen titled “The Nakba as Carnival”, which urged readers to “stop denying the Nakba and start enjoying it.”

The paper also published official statements from Israeli soldiers claiming that the mass Palestinian displacement resulted from Arab promises to evacuate temporarily. In doing so, it endorsed the state’s official narrative that blamed Palestinians and Arabs for the refugee crisis—paving the way for viewing internally displaced Palestinians as enemies or traitors. This rationale helped justify the continuation of Israeli military rule over Palestinian citizens until 1966.

Internationalization of the Narrative

After the establishment of the State of Israel, Yedioth Ahronoth embarked on vigorous efforts to connect with international media. Its journalists began publishing opinion pieces in major European and American newspapers to promote Israel as a democratic state surrounded by hostile and backward neighbors. Prominent contributors included Emmanuel Bar-Kadma, Chika Levit, Aharon Weiss, Aharon Bihor, and Moshe Verdi, among others.

These efforts were successful.

The Israeli narrative, focusing on nation-building and societal resilience, began to dominate coverage in European and Western media. Yedioth became a go-to source for regional news in Western wire services like the Associated Press and Reuters.

Between 1956 and 1973, the newspaper played a leading role in shaping Western opinion through joint reports with French and British outlets. Writers like Yeshayahu Ben-Porat, Adam Baruch, and Ram Oren emphasized the threat posed by Arab regimes and tied these threats to Israeli national security.

They framed the Arab-Soviet alliance as a menace to Western capitalism—with Israel as its democratic outpost—helping cultivate domestic support for Israel’s military build-up and expansionist policies.

In a context of Middle East instability and growing alignment between European and Israeli perspectives on the Arab world, Western newspapers came to rely heavily on Yedioth Ahronoth to reflect a pro-Western regional narrative. The paper also partnered with major international outlets such as Le Monde, Le Figaro, and The New York Times.

The 1973 War: A Pivotal Moment

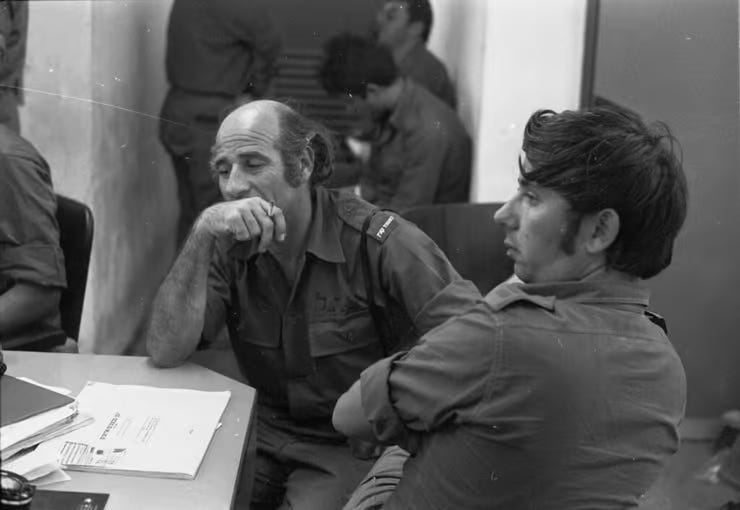

The 1973 October War (Yom Kippur War) marked a significant turning point in the paper’s history. Editor Dov Yudkovsky made the strategic decision to distribute the newspaper for free to all Israeli military conscripts. He dedicated large portions of the paper to letters exchanged between the home front and the battlefield, along with exclusive and rapid updates from the frontlines.

This move expanded Yedioth’s readership from working-class and middle-professional circles to include military families and conscripts. It became more accessible to a wider range of readers.

Framing the war as both necessary and just, Yedioth supported the offensive while also critiquing the intelligence and military failures of the Israeli government. This dual approach played a role in the resignation of Golda Meir’s government, enhancing the paper’s reputation both domestically and abroad.

Between the 1973 war, the rise of the Black Panthers movement, and the political upheaval of 1977, Yedioth Ahronoth flourished. During Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in the early 1980s, the paper’s circulation peaked, reaching up to 500,000 copies on Fridays. It became widely known as “the country’s newspaper and its mirror,” transcending party affiliations and solidifying its status as Israel’s most-read and most-distributed publication.

Technological Innovation and Market Domination

Yedioth Ahronoth was also a pioneer in adopting new media formats. It launched Israel’s first television magazine, Yedioth Televax, and developed its own independent printing system by establishing two separate presses. The paper also entered the cable media market and acquired shares in television ventures like Channel 2.

Later, it launched a news website—Ynet—which quickly became Israel’s most popular digital news platform.

While precise circulation figures remain unpublished, the Yedioth Ahronoth Group, owned by the Moses family, is now considered the largest media conglomerate in Israel. It controls between 50% and 75% of the print media market and maintains a strong presence across other media sectors.

Its only real competition is Israel Hayom, a free newspaper founded in 2007 and funded by American businessman Sheldon Adelson. Despite its free distribution model, Israel Hayom is now the most widely circulated paper in Israel and remains Yedioth’s primary challenger.

Manipulation and Ethical Violations

Yedioth Ahronoth’s dominance has not always been achieved through ethical means—even within Israel. Its singular focus on increasing distribution and profits often clashed with traditional journalistic values or public interest.

In September 1995, it was revealed that Yedioth’s editorial department had been involved in wiretapping the phones of executives at rival newspapers.

The scandal particularly implicated Ma’ariv. While reports suggested that both sides engaged in mutual spying, the editor-in-chief of Yedioth Ahronoth was forced to resign after his direct involvement was proven. Simultaneously, a senior figure at Ma’ariv was arrested for plotting an assassination against his competitors.

More recently, Yedioth has continued to stir controversy. In 2009, it published a story based on misleading reports about the health condition of captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who was being held by Palestinian resistance. The report falsely claimed that Shalit had suffered severe injuries—claims later disproven.

During Israeli elections—whether parliamentary or presidential—the privately-owned Yedioth has faced consistent accusations of bias against certain parties, particularly right-wing ones like Likud. These biases have led to recurring doubts about the paper’s objectivity and journalistic credibility.

In 2014, the paper was accused of manipulating its circulation figures to exaggerate its reach and attract higher advertising revenue. Investigations revealed that it had inflated both sales and distribution numbers, prompting formal inquiries and criticism from rival media outlets.

The paper has also faced ethical scandals. In 2016, one of its senior journalists was accused of sexually harassing female colleagues, sparking a media and human rights outcry and drawing attention to harassment within Israeli newsrooms.

In early 2017, Israeli police investigations revealed a secret agreement between then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and publisher Arnon Moses. The deal allegedly offered favorable media coverage of Netanyahu and his government in exchange for limiting the distribution and influence of Israel Hayom. This scandal became known as Case 2000, and Netanyahu is still facing legal scrutiny over it.

In 2023, Yedioth was heavily criticized for its manipulative coverage of anti-government protests. The paper was accused of inflating protester numbers at times and exaggerating the violence between demonstrators and police at others. These actions reignited questions about the paper’s reliability and its shifting editorial stances.

Notably, Yedioth has rarely issued apologies or editorial corrections—apart from the wiretapping incident. Even when investigations clearly undermined its journalistic neutrality, the paper’s leadership showed little interest in re-evaluating its practices or reforming its editorial policies.

Writing in Hebrew for the Arab Reader

On the Arab and regional front, Yedioth Ahronoth’s discourse began to evolve by the late 1960s and early 1970s. As the paper expanded its influence, its tone toward Arab nations grew less overtly hostile and more aligned with international media and diplomatic standards.

This shift was particularly evident during Israel’s war in Lebanon—especially after the withdrawal of Palestinian fighters—when the paper openly criticized Israeli massacres against Arabs and Palestinians and even called for an Israeli withdrawal from Lebanon.

However, it simultaneously advocated for the establishment of local proxies for Israel in both Lebanon and Syria to help maintain Israeli security. It linked Arab economic fragility and state weakness to Israel’s relative strength, reinforcing the image of a superior, modern state.

With the rise of an Arab “dovish” current that no longer objected to Israel’s existence, Yedioth’s tone shifted dramatically from its Nakba-era rhetoric. It gradually moved from blaming Arab regimes for the Palestinian refugee crisis to portraying some of these regimes as potential peace partners or moderates.

The newspaper also began spotlighting the inner workings of Arab governments and their covert relations with Israeli officials—even when such ties operated under international cover. At the same time, Yedioth maintained a cautious editorial stance that reflected deep-rooted Israeli security suspicions about Arab intentions.

A notable example is the paper’s coverage of the Camp David Accords and Anwar Sadat’s 1977 visit to Jerusalem. Yedioth ran a full-page interview with IDF Chief of Staff Mordechai Gur under the headline: “What Prompted Sadat to Visit Jerusalem?” The interview warned that the visit might be a deceptive maneuver to mask an impending Egyptian attack.

Yet on the day of Sadat’s arrival, the newspaper dramatically shifted its tone, calling the visit “historic” and detailing unprecedented security, medical, and media preparations: 21-gun salutes, an American-loaned armored limousine, emergency blood units, and an entire hospital wing cleared at Hadassah in case of assassination attempts. It highlighted the visit’s potential to “fracture the Arab world.”

This pattern of initial skepticism followed by celebratory coverage was repeated during the Madrid peace talks, the Oslo Accords, and the Wadi Araba agreement with Jordan. As Arab media remained tightly censored, Yedioth often broke exclusive details that were later picked up and cited widely in the Arab world.

It was the first to report the Oslo agreements, thanks to journalist Shimon Shiffer, and conducted indirect interviews with representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

Perhaps its most symbolic moment came with the first-ever interview between Israeli media and King Hussein of Jordan, conducted by journalist Smadar Perry. The now-iconic photo showed King Hussein lighting a cigar for the journalist, echoing a previous image where he lit one for Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. The paper described the peace with Jordan as “unique,” and called Jordan a “mirror for Israel,” according to Perry’s characterization.

This was followed by a series of interviews with Arab and Palestinian leaders—either directly or indirectly—including Mohammed bin Zayed, Abdullah bin Zayed, Yusuf bin Alawi (Oman), Ahmed Aboul Gheit (Arab League), Abdullatif Al Zayani (Bahrain), Yasser Arafat, Saeb Erekat, Mohammed Dahlan, and others.

To this day, Yedioth Ahronoth continues publishing damaging exposés and leaked reports about Arab positions that support Israeli occupation. Headlines include: “Saudi Arabia Endorses Camp David,” “Are You Jewish? Welcome,” “War Diaries,” “Complications with Syria,” and “New Israeli Proposal: Egypt to Absorb Refugees in Exchange for IMF Debt Relief.”

Propaganda of Genocide

Since its inception, Yedioth Ahronoth has maintained an aggressively hostile tone toward Palestinians in all areas of their existence, regardless of their actions. Its writers often appeared less like journalists and more like foot soldiers—justifying the mass expulsion of Palestinians during the Nakba as a “natural consequence of war” and portraying refugees not as victims of ethnic cleansing but as deserters.

The paper often approached Palestinian rights from a military lens, assigning military correspondents to cover Palestinian affairs and consistently publishing politically and morally charged exposés aimed at discrediting the Palestinian cause. Its pages reveled in narratives of conquest, celebrating the seizure of Palestinian lands and towns.

According to the paper’s archives, and in homage to its military correspondent Eitan Haber, who started out covering Irgun attacks on Palestinians, Yedioth published special editions during every Israeli war, glorifying military achievements.

Following the 1967 war, Yedioth ran a front-page headline by Eitan Haber titled: “The Temple Mount Is in Our Hands.” Haber wrote, “I’ve never felt excitement like the moment I received news that Israeli forces had captured the Old City.”

This euphoria extended beyond Jerusalem to the Oslo negotiations, peace handshakes in Washington, and even security coordination visits with Palestinian officials.

Despite its apparent enthusiasm for the peace process, the newspaper continued its aggressive editorial posture toward Palestinians—frequently breaking stories of alleged corruption, scandals, or conspiracies involving Arab and Palestinian figures.

One of the most sensational cases was an interview with Tzipi Livni, in which she claimed that several Palestinian officials—Yasser Abed Rabbo, Saeb Erekat, and others—were involved in moral transgressions that could be exploited for intelligence purposes.

The paper also broke the scandal involving expired COVID-19 vaccines supplied to the Palestinian Authority. Following the exposé, the PA held a press conference announcing the cancellation of the agreement with Israel after the vaccines were found to be unfit for use.

In parallel, Yedioth tracked the progress of Israeli-Palestinian security coordination and secret negotiations, publishing detailed reports on meetings, agreements, and painful concessions. It also uncovered brainwashing initiatives sponsored by the PA, targeting Palestinian police and civil servants with normalization workshops involving Israeli agencies.

Militarism and the Gaza Wars: From the Nakba to Annihilation

Militarily, Yedioth Ahronoth maintained its combative tone from the Nakba until today. In fact, its rhetoric became more aggressive in parallel with the intensification of Israeli assaults on Gaza. The paper consistently adopted a pro-military stance, supporting Israel’s brutal campaigns and portraying them as essential for national security.

Its writers promoted the idea of “voluntary displacement” as an alternative to acknowledging the reality of forcible expulsion. This narrative reappeared most starkly following the October 7, 2023 attacks by Hamas, after which Yedioth ran an editorial declaring: “The Hamas attack is the starting point for everything Israel must now do.”

In that coverage, Palestinians were stripped of humanity. The newspaper’s editorial line shifted to fully back military escalation, focusing instead on rallying a fragmented Israeli society behind the war machine.

Positioning itself somewhere between the left-leaning idealism of Haaretz and the far-right populism of Ma’ariv, Yedioth continued to justify Israeli operations in Gaza with rhetorical flourishes about the “enormous pressure” Israeli leaders faced at home and abroad following the gruesome scenes from October 7.

At the same time, it glorified Israeli soldiers—portraying them as “patriotic,” “adventurous,” and “heroic”—in a style that verged on tabloid sensationalism.

The newspaper also employed euphemisms to disguise reality. Illegal settlements were called “new neighborhoods.” Annexation became “service expansion.” Reoccupation of Gaza was “returning to the Strip.” Ethnic cleansing was reframed as “cleansing,” a sanitized term that gained international acceptability despite its underlying racism.

This strategic use of language coincided with a broader transformation in the media toolkit. While earlier decades relied on text, the modern phase used a mix of television appearances and embedded journalism. Writers transitioned from print to broadcast, offering real-time commentary that promoted destruction and violence against Palestinians—often under the misleading term “voluntary displacement.”

Several Yedioth journalists embedded themselves with the Israeli military during the 2023 Gaza War, riding in armored vehicles and tanks and boasting about their access to scenes of devastation. They promoted their “scoops” about destroyed buildings and burned neighborhoods.

The newspaper ran a front-page story in September 2024 about the discovery of six Palestinian captives’ bodies in tunnels under Gaza, which had been located by Israeli forces. Meanwhile, foreign media outlets were barred from entering or reporting independently on the conflict and its consequences.

In sum, the history of Yedioth Ahronoth—rife with political exposes, military embeds, and high-profile leaks—reflects a consistent attempt to dominate the media landscape. Whether by breaking scandals or discrediting Palestinian and Arab political figures, the newspaper has operated as an instrument of ideological warfare more than as a journalistic enterprise.

Its roots lie firmly within the structure of the Israeli colonial project. It operates under tight censorship and passes through the blades of state review. And whatever truth it may publish, it does so only when that truth serves Israel’s security and international image.

Even when Arab journalists and readers cite it as a source, what they consume is not independent information—it is carefully packaged propaganda, weaponized through Hebrew letters, designed to influence Arab perception and normalize Israeli hegemony.